Iowa Professor Helps Native Families Piece Together Past

PHOTO COURTESY CARRIE LOWRY SCHUETTPELZ

Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz, an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, teaches public policy at Iowa, where she is also director of the Native Policy Lab.

PHOTO COURTESY CARRIE LOWRY SCHUETTPELZ

Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz, an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, teaches public policy at Iowa, where she is also director of the Native Policy Lab.

For many older Native Americans, one of their earliest memories is being snatched from their family. Taken hundreds of miles away to attend religious or government-run boarding schools, they were forced into a new language and religion, likely beaten, and given little food or medical care.

Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz (06BA) is well acquainted with these stories, documented for tens of thousands of Native children from 1860 until 1978. Most survivors, she says, left the schools with nothing tangible of themselves—no letters, no report cards, not even a photograph to chronicle their existence.

One survivor she interviewed had no pictures of himself before age 16. After connecting the man with class worksheets and handwritten cards from his youth, Schuettpelz says, “It became clear to me that this was something more people should experience. I felt really compelled to do this work.”

The work has become known as Project Return—one of two endeavors that led to a prestigious $1.1 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for Schuettpelz, associate professor of practice and director of undergraduate studies in the University of Iowa School of Planning and Public Affairs. “Her efforts to return documents have had a transformative impact on the lives of survivors and their families,” says Libby Washburn, associate CEO of the Native American Agriculture Fund.

Aiding Survivors and Involving Students

In 2024, while on tour for her first book, The Indian Card: Who Gets to Be Native in America, Schuettpelz met Native American readers frustrated at being unable to legally establish their heritage through documentation. The professor learned that no national initiative helped boarding school survivors retrieve their records from archives—a complex and often pricey process.

“I hadn’t fully appreciated how many survivors are still part of every community, every tribe. The sheer magnitude was eye-opening,” she says. “I wanted to expand this nationally. The grant allows us to do that.”

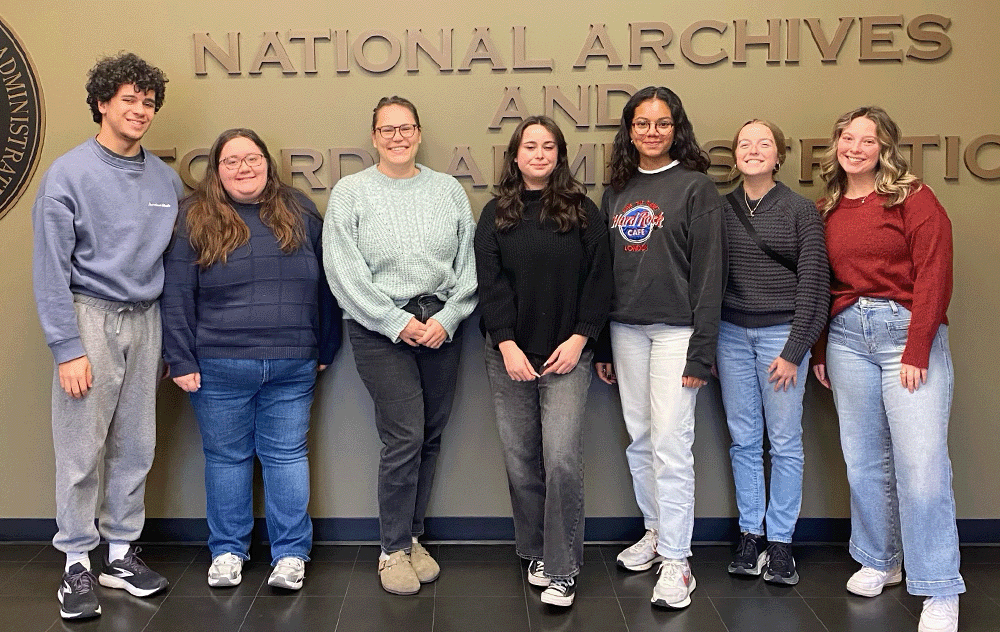

The Mellon grant, along with partnerships with the university’s Center for Social Science Innovations and its Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio, has also allowed undergrad and graduate students to support research, which often takes them to other universities and repositories across the country.“You can hear about these documents in the classroom, but traveling to Kansas City and Fort Worth literally put history in my hands,” says Joseph Maxwell, a UI student who graduates this spring from the Master of Urban and Regional Planning program, with a concentration in land use and environmental planning. Maxwell, a descendant of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), says that peering into the eyes of the schoolchildren in old photographs who are now elders helped connect him with the people his research serves.

“The experience has allowed the opportunity to ask my own research questions,” he adds, “and taught me a lot about where I fit into the broader picture.”

Past as Prologue

Schuettpelz also has a personal connection to her research, having become an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina at age 6. She earned bachelor’s degrees from Iowa in political science and anthropology before heading to Harvard. With a master’s in public policy, she spent seven years as a policy adviser at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, focusing on homelessness policy and Native issues. She then earned an MFA in creative writing at Wisconsin before joining the UI faculty and leading Iowa’s Native Policy Lab.

Schuettpelz’s Mellon grant also supports Project Trust, which uses land mapping tools and records to help Native Nations develop plans to regain ownership and access to land. How is the long history of land loss still affecting tribes? How much is recoverable—not just for monetary purposes, but for pride, worth, and a sense of heritage? Questions like this are “coming more into the public consciousness,” Schuettpelz believes.

Many of Schuettpelz’s research pursuits derive from talking with people about policy changes they’d like to enact. Through these projects and her writing, she brings greater public awareness and develops a new generation of researchers.

In any endeavor, “Professor Schuettpelz’s work is marked by a deep commitment to Native communities and a thoughtful approach to issues of identity and justice,” says Washburn. “She approaches her work with exceptional dedication and empathy.”

PHOTO COURTESY CARRIE LOWRY SCHUETTPELZ

Joseph Maxwell (pictured at left) joins other UI students on a research trip to the National Archives and Records Administration.

PHOTO COURTESY CARRIE LOWRY SCHUETTPELZ

Joseph Maxwell (pictured at left) joins other UI students on a research trip to the National Archives and Records Administration.