After Tragic Loss, Iowa TRACERS Team Brings NASA Mission to Launch

PHOTOS ABOVE COURTESY SPACE X

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, like the one pictured here, is scheduled to deliver the TRACERS satellites into orbit.

PHOTOS ABOVE COURTESY SPACE X

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, like the one pictured here, is scheduled to deliver the TRACERS satellites into orbit.

Later this year, a 230-foot-tall Falcon 9 rocket is scheduled to roar skyward from California’s Vandenberg Space Force Base, heralding the start of a landmark University of Iowa-led mission. Aboard the SpaceX vessel, twin spacecraft known as TRACERS—Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites—will begin their journey to study Earth’s mysterious magnetic interactions with the sun. The satellites will be packed with scientific instruments along with two small, but meaningful, tokens.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Late professor Craig Kletzing speaks at the UI Presidential Lecture in 2022.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Late professor Craig Kletzing speaks at the UI Presidential Lecture in 2022.

Before shipping the technology payloads to California last summer for assembly, Iowa researchers embedded a pair of purple guitar picks atop the main electronics boxes in each TRACERS satellite. The mementos belonged to the mission’s architect, UI physicist Craig Kletzing, who died from cancer in 2023 at age 65. In 2019, Kletzing and his collaborators secured a $115 million contract from NASA for TRACERS—the largest research award in the university’s history—and Kletzing served as the mission’s principal investigator until his death. The picks ensure that a symbolic piece of the guitar-playing professor will sail through the magnetosphere, a region of space that he spent much of his life studying.

The launch of TRACERS will provide scientists with new insights about space weather and help them better forecast potentially catastrophic solar storms. It’s also a testament to the perseverance of Kletzing’s team, which ensured his vision became reality.

“As Craig got sick, there was an enormous groundswell from all the people he knew, all the people working on his project; we had to make Craig’s mission a success,” said UI associate professor David Miles, who succeeded Kletzing as principal investigator, during a symposium honoring his late colleague last year in Iowa City. “We had to carry it forward, we had to deliver it, and we had to see it on orbit. One of the things you can recognize about the impact Craig left was how many people rose to the occasion to make his last mission a success.”

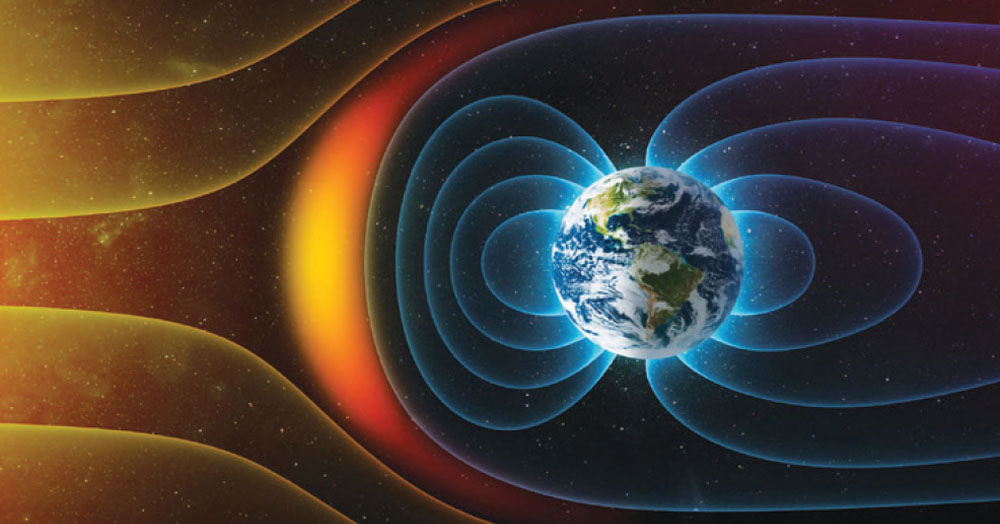

ILLUSTRATION COURTESY NASA

TRACERS will study how the solar wind interacts with the Earth’s magnetosphere, the region of space around our planet influenced by its magnetic field.

ILLUSTRATION COURTESY NASA

TRACERS will study how the solar wind interacts with the Earth’s magnetosphere, the region of space around our planet influenced by its magnetic field.

A Magnetic Mystery

The mission’s origins can be traced, so to speak, to a dinner among colleagues during an American Geophysical Union conference about a decade ago. Kletzing was at a table that included Stephen Fuselier (83MS, 84PhD), a scientist at Southwest Research Institute, when they began spitballing NASA mission ideas—as space physicists are wont to do over dinner. At the time, Kletzing and Fuselier were collaborating on a NASA sounding rocket experiment named TRICE-2, which would launch in 2018 from Norway to investigate an enigmatic process in the Earth’s upper atmosphere called magnetic reconnection. The phenomenon occurs when charged space particles, known as the solar wind, stream into our planet’s magnetic field in a region over the poles called the cusp, where the Earth’s magnetic field lines converge. That coupling of energy helps create the auroras, or the northern and southern lights, but it can also wreak havoc on Earth’s technology.

Kletzing hoped to answer a fundamental question that had puzzled physicists for decades: Is magnetic reconnection temporarily or spatially variable? In other words, does the solar wind enter Earth’s atmosphere like a water faucet turning on and off, or does it happen continuously across multiple points of the cusp, like a hose watering a yard? Or could it be a combination of the two? Kletzing and Fuselier wondered if they could build on their work with TRICE-2 to solve the mystery by sending two satellites into orbit around Earth’s poles, one following the other, recording data through a wide range of solar wind conditions.

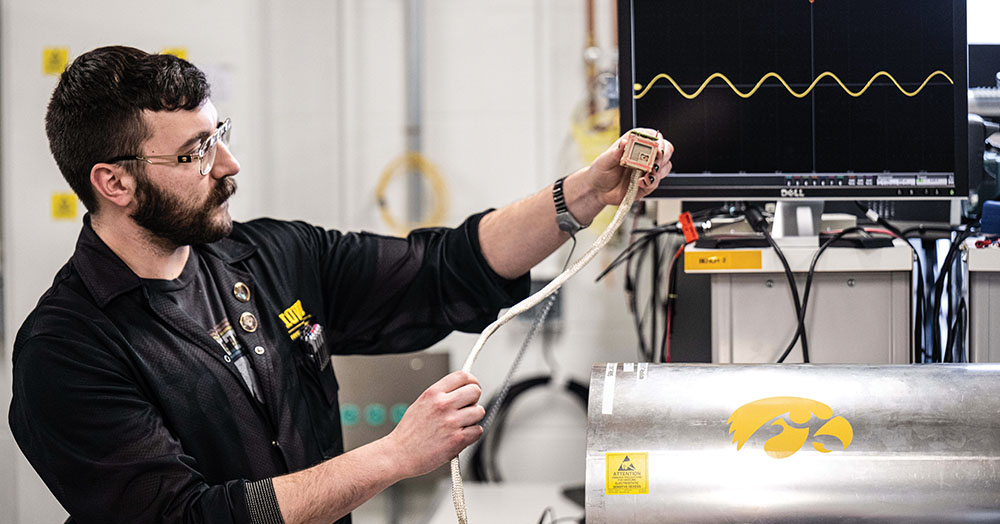

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

UI aerospace design engineer and electrical engineer Samuel Hisel works with a TRACERS instrument.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

UI aerospace design engineer and electrical engineer Samuel Hisel works with a TRACERS instrument.

That dinner conversation ultimately sparked a proposal through NASA’s Small Explorers program, which develops highly focused and—at least in NASA terms—low-cost scientific missions. Kletzing knew that determining precisely how the sun’s energy enters Earth’s atmosphere could lead to improved forecasting of solar weather, which NASA considers an urgent priority. Solar storms can disrupt the technology we depend on each day, including satellite communications, GPS systems, and power grids, as well as pose a threat to manned space flights.

Collaborating with Fuselier and other physicists around the country, Kletzing’s initial pitch for TRACERS earned a $1.25 million grant from NASA to conduct a larger, 11-month mission concept study. The full-fledged 900-page proposal struck a chord at NASA headquarters. In mid-2019, Kletzing was in Germany with his wife, musician Jeanette Welch (00MA), at a scientific meeting when his phone lit up with congratulatory messages: TRACERS was a-go. NASA would provide $115 million to build and launch the satellites, and the University of Iowa would helm the mission.

As principal investigator, Kletzing assembled what he called an “all-star team” from Iowa, Southwest Research Institute, University of California Berkeley, University of California Los Angeles, and other institutions. Though Kletzing had been involved in more than 30 near-Earth and space missions in his career, this was the first time he’d serve as the principal investigator on a NASA mission of this scale—what he called a “capstone career achievement.”

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

The main electronics boxes aboard each of the TRACERS spacecraft include a tribute to late UI professor Craig Kletzing that features one of his guitar picks.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

The main electronics boxes aboard each of the TRACERS spacecraft include a tribute to late UI professor Craig Kletzing that features one of his guitar picks.

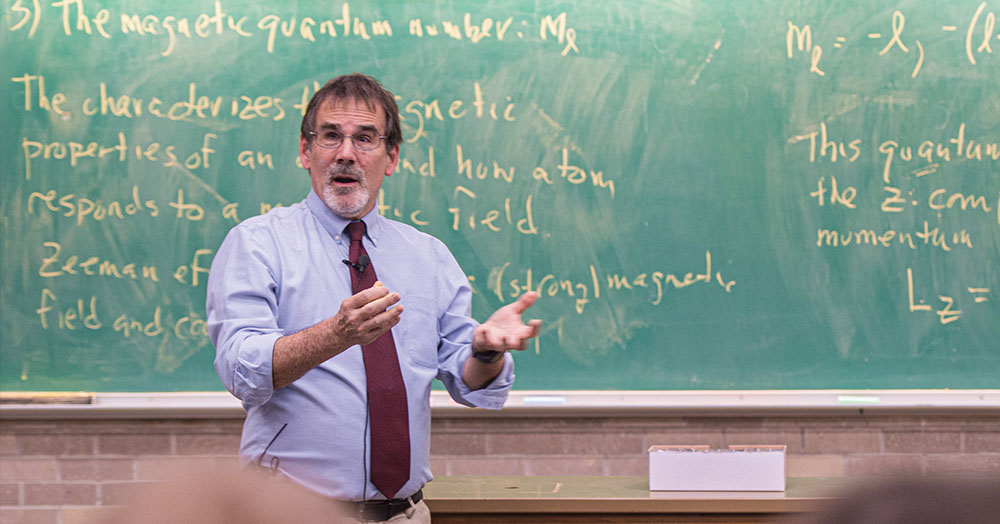

A Lifetime of Curiosity

In late 2019, Kletzing sat down with Iowa Magazine as work commenced on TRACERS. Like the auroras he studied, the dynamic professor seemed to energize the atmosphere around him with his enthusiasm for physics. “TRACERS is a basic science mission,” Kletzing explained in his office at Van Allen Hall. “We’re doing it because we want to understand how things work. But there’s a long history of doing basic research and coming up with things that no one expected, which turns into something important. … That’s why it’s important we invest in basic science: because you just don’t know where the next payoff is going to come from.”

Kletzing’s team developed six main research instruments for the twin satellites, including three components designed and built in Van Allen Hall’s labs led by UI researchers Miles, George Hospodarsky (88BS, 92MS, 94PhD), and Jasper Halekas. (Halekas had come up with the TRACERS acronym in the concepting phase, earning a bottle of red wine from Kletzing.) Meanwhile, Fuselier, a vice president at Southwest Research Institute, was tapped as deputy principal investigator and led the development of an instrument called the Analyzer for Cusp Ions.

Fuselier, who had also collaborated with Kletzing on NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission that launched in 2015, recalls Kletzing’s rare ability to distill complex scientific challenges into achievable objectives. A common refrain from Kletzing on TRACERS, says Fuselier, was “How can we make this simpler?”

“We had the advantage of having some extraordinary leadership from Craig,” says Fuselier. “Craig knew how to get input from his team, but he also knew when to make a decision. All the way along the proposal development process and mission development, his decisions were the right ones. It was an enormous privilege to work with Craig and TRACERS, and this mission is going to be a fitting tribute to his insight and leadership.”

Kletzing grew up in Sacramento, California, where, as a child, he overcame a rare form of hereditary cancer that cost him his sight in one eye. His early health problems never tempered his curiosity, however. Kletzing studied at UC-Berkeley, where he became fascinated with the physics behind the auroras, then earned a PhD at UC-San Diego under the wing of professor Carl McIlwain (56MS, 60PhD), a former student of legendary UI physicist James Van Allen (36MS, 39PhD). In 1996, Kletzing joined the Iowa faculty, continuing a legacy of space research begun by Van Allen, who famously discovered the radiation belts in the Earth’s magnetosphere.

Tragically, Kletzing was diagnosed with cancer again shortly after bringing TRACERS to Iowa. As the mission progressed, so too did the disease.

He died Aug. 10, 2023, at his home in Iowa City. But in the weeks before Kletzing’s death, NASA officials traveled to Iowa City to present him with signed documentation confirming that the satellites had cleared a critical development stage and were approved for launch.

“He left this Earth knowing that TRACERS was going to go,” says Fuselier. “It was just a matter of when.”

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Late professor Craig Kletzing in the classroom.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Late professor Craig Kletzing in the classroom.

Guitars and Rockets

Last June, colleagues, friends, and former students from around the country gathered in Iowa City to celebrate Kletzing’s life and scientific legacy. They remembered him as a magnetic mentor and scientist who was as warm and generous as he was brilliant. During a symposium inside Van Allen Hall and a reception at Old Brick, physicists shared stories about Kletzing’s love of food, wine, traveling, and music.

Kletzing played guitar in many bands over the years, including some with science-inspired names like Brace for Blast and Bipolar. Most recently, he jammed with a rock, jazz, and blues ensemble called Fork in the Road, which also included his wife, Jeanette, on bass. Kletzing would sometimes bring his guitar to class to help students “get a little more enthusiastic about physics than they were before,” remembers UI associate professor Allison Jaynes. “They just loved that; they went crazy for it,” Jaynes said at the symposium. “Here’s this guy with a ponytail and an electric guitar who’s also a world-renowned physicist who does rockets and satellites.”

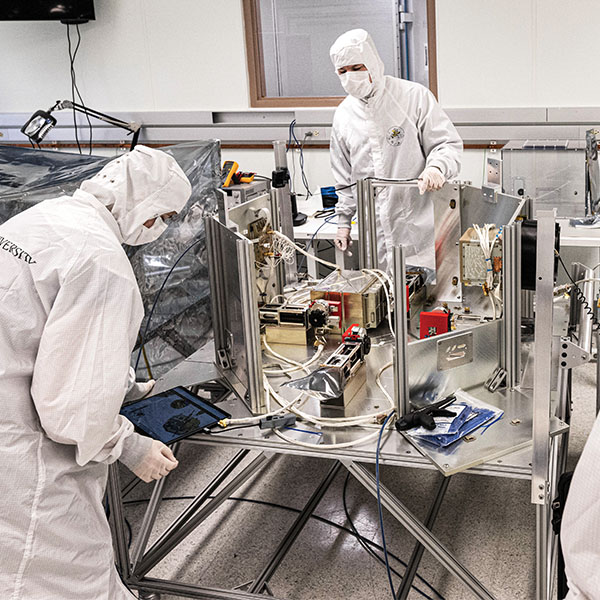

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

UI aerospace principal engineer and mechanical engineer Rich Dvorsky, left, and aerospace quality engineer Garret Hinson work with TRACERS instruments inside Van Allen Hall.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

UI aerospace principal engineer and mechanical engineer Rich Dvorsky, left, and aerospace quality engineer Garret Hinson work with TRACERS instruments inside Van Allen Hall.

Jaynes still remembers the day a student knocked on Kletzing’s office door while the two professors were meeting. Kletzing and Jaynes were co-teaching an undergraduate physics course at the time, and the student told them that a group from the class had procured a copy of the solutions manual and was using it to work out problems ahead of the test. “Let me get this straight,” said Kletzing to the informant. “There’s a group of students who are going through every chapter and practicing hundreds of physics problems in advance of my exam? That’s not cheating; that’s studying. Get a copy of that book and do it too.”

While leading a $165.7-million space mission (NASA allocated an additional $50 million after the initial $115 million grant), Kletzing remained dedicated to the classroom. When NASA’s top officials paid a visit to Iowa City in 2019 to tour the UI’s facilities, Kletzing skipped a breakfast with the administrators so he wouldn’t miss his 8:30 a.m. lecture for College Physics I, an introductory course with 275 students.

Even as his health deteriorated, Kletzing imagined new opportunities for students to gain hands-on training through TRACERS. Kletzing drew up a successful proposal to NASA for a smaller student-led mission that would complement the research of TRACERS, and he enlisted Jaynes to guide the project. Today, the $3 million project has allowed students to build instruments to investigate the cusp aboard a sounding rocket. Doctoral students from the UI and other institutions lead and manage the mission—named Observing Cusp High-altitude Reconnection and Electrodynamics, or OCHRE—alongside Jaynes and other senior scientists.

“A couple of weeks before he passed, I’d go visit him and spend time with him, and he was still asking about that student project,” Jaynes said of Kletzing. “Even at the very end, he was wondering how that was going and when that was going to get started and all the cool stuff that was going to come out of that.”

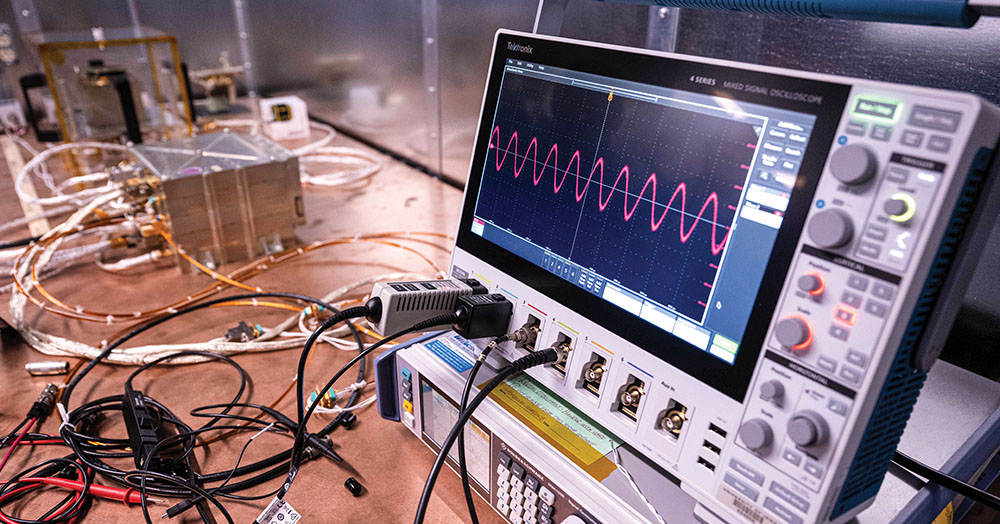

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Electronic components of the satellites undergo testing at Van Allen Hall.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Electronic components of the satellites undergo testing at Van Allen Hall.

Music of the Spheres

After assembling the full instrument suite for TRACERS at Van Allen Hall, the UI team shipped the payloads last year to Boeing subsidiary Millennium Space Systems in California, where engineers constructed and tested the satellites. From there, the spacecraft are scheduled in early April to be transported to Vandenberg Space Force Base for integration in the launch vehicle, the SpaceX Falcon 9.

“This team has been truly incredible,” Skyler Kleinschmidt, TRACERS program executive at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said after the satellites were completed in November. “Building a spacecraft is never easy, but seeing the team work together through all of the challenges that they have encountered is inspiring.”

ILLUSTRATION COURTESY NASA

A rendering of one of the TRACERS spacecraft

ILLUSTRATION COURTESY NASA

A rendering of one of the TRACERS spacecraft

For Kletzing, launch days were always special, marking the culmination of years of design, development, and testing, and the start of the most important stage: data collection. “There’s a great satisfaction when you get something flying, and you get some good measurements back,” Kletzing said in a 2020 interview for the UI’s Chat From the Old Cap series. “You can predict all you want, but then you go and measure, and sometimes you go, ‘Oh, it’s not quite what I thought it was.’ Those are where the aha moments come, where you go, ‘Huh, that’s not what we expected to see; now we’ve got to go put on our thinking caps and figure out what happened.’”

David Miles and other members of the UI TRACERS team will be on-site for liftoff to provide technical support. They’ll watch as the Falcon 9 rises from a column of flames, disappears into the upper atmosphere, then deploys the satellites 350 miles above Earth. If all goes to plan, “Craig’s mission,” as his colleagues fondly call it, will soon deliver new data to help scientists better understand the powerful forces harmonizing throughout the universe—something the ancient Greeks described as the music of the spheres.

It makes it all the more fitting that a pair of purple guitar picks will be along for the ride.

Says Miles: “A little bit of Craig’s curiosity will go to space one more time.”