Inside UI Health Care’s Burn Treatment Center

When emergency crews flew 8-year-old Brody Pearston across the state to the Burn Treatment Center at University of Iowa Health Care this past June, the situation was critical.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

Brody Pearston had second-degree burns covering nearly half his body when he arrived at the Burn Treatment Center in June 2025.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

Brody Pearston had second-degree burns covering nearly half his body when he arrived at the Burn Treatment Center in June 2025.

Just hours earlier, Brody had gathered with his parents and older brother around a tabletop s’mores maker on their deck. A week into summer break and with no baseball games on the calendar for the boys that evening, the Pearstons were enjoying some family time at home in Polk City, Iowa.

But in an instant, an idyllic summer night turned into a nightmare. A bottle of isopropyl alcohol, used to fuel the s’mores maker, caught fire and exploded. Flames covered Brody’s arms and legs. His father, Durk—a state trooper and no stranger to emergency situations—smothered the fire with his bare hands. But the flames had spread too fast, leaving Brody with devastating injuries.

The ensuing hours were a blur. Doctors in nearby Des Moines stabilized him, but it became clear that his burns were beyond what could be handled locally. Brody was airlifted to Iowa City, home to the state’s only burn center.

“The hardest part as a parent is just watching your child go through something so extreme, and you have no control over it. You just want to take it away from him.” Ashley Pearston

His arrival marked the beginning of a harrowing 38-day hospitalization. Like many of the hundreds of burn victims who receive specialized care at the UI Burn Treatment Center each year, Brody’s injuries were as complex as they were painful. His legs, arms, and right hand were nearly fully covered in burns. His torso and cheeks, chin, and mouth also were affected, though less severely. All told, 45 percent of his body was covered in deep second-degree burns.

“The hardest part as a parent is just watching your child go through something so extreme, and you have no control over it,” says Brody’s mother, Ashley Pearston. “You just want to take it away from him.”

In the coming weeks, Brody would endure close to 10 surgeries, including two skin grafts, as well as a dangerous bout of sepsis. Through it all, the experts with Iowa’s multidisciplinary burn team—including surgeons, physical therapists, and social workers—were by the family’s side as Brody fought to heal.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

Iowa men's basketball coach Ben McCollum paid Brody a visit at the Burn Treatment Center.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

Iowa men's basketball coach Ben McCollum paid Brody a visit at the Burn Treatment Center.

Growing the Capacity for Care

In medicine, every day holds the potential for heartbreak. Yet on the eighth floor of UI Health Care Medical Center, where the Burn Treatment Center has operated since 1996, the staff shoulder a weight few others experience. They often see the worst of the worst—and are prepared to meet it.

PHOTO: LIZ MARTIN/UI HEALTH CARE

Burn Treatment Center director and surgeon Samuel Jones oversees treatment for the nearly 300 patients admitted to the center each year.

PHOTO: LIZ MARTIN/UI HEALTH CARE

Burn Treatment Center director and surgeon Samuel Jones oversees treatment for the nearly 300 patients admitted to the center each year.

“We don’t want anyone to get burned, but if you do, we’re here to take care of you,” says Samuel Jones, the center’s director and UI surgeon who oversaw Brody’s treatment. “It’s a very unique specialty, because most burn injuries scare anyone who doesn’t take care of burn patients.”

The center—one of 77 American Burn Association–verified programs nationally and one of just 39 that treat both adults and children—provides care for patients from across Iowa and neighboring states. Among the most common injuries treated at the unit are burns from hot liquids and flames, as well as chemical and electrical accidents. Some cases follow seasonal patterns: frostbite in the winter, and severe sunburns and fireworks-related injuries in the summer. Beyond burns, the center treats life-threatening skin conditions such as toxic epidermal necrolysis, a disorder marked by widespread blistering and skin detachment, as well as necrotizing soft tissue infections, more commonly known as flesh-eating bacteria.

To meet the state’s growing needs for burn care, UI Health Care is in the midst of the largest renovation and expansion in the center’s 30-year history.

About 300 patients are admitted each year, many of whom face lengthy hospitalizations and months of rehabilitation. The center also manages nearly 3,000 outpatient visits annually for dressing changes, physical and occupational therapy, scar management, psychological support, and other long-term treatments. At the same time, the center is home to a flourishing research program, including clinical trials that provide patients with access to cutting-edge therapies.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

UI Health Care is renovating its Burn Treatment Center to improve care and accommodate more patients like Brody.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

UI Health Care is renovating its Burn Treatment Center to improve care and accommodate more patients like Brody.

To meet the state’s growing needs for burn care, UI Health Care is in the midst of the largest renovation and expansion in the center’s 30-year history. The $14.9 million project, scheduled for completion by summer 2026, will modernize inpatient spaces with new hydrotherapy rooms, staff work areas, and support facilities. It will also increase capacity from 17 to 21 beds. A new outpatient clinic will feature a dedicated entrance, exam and procedure rooms, a waiting area, and additional support spaces.

The expansion means that fewer acute patients will need to be transferred to other hospital floors, and pediatric burn patients who are sometimes housed in Stead Family Children’s Hospital can stay within the unit. It will also allow the center to provide care across every phase of recovery, from the critical moments after injury through months or years of reconstructive treatment, rehabilitation, and emotional healing.

“It’s not just about seeing the wound and putting something on it and sending the patient home,” says Jones, the Clara Smith Clinical Professor in Burn Treatment. “It’s a comprehensive specialty that requires multiple disciplines—physical therapy, occupational therapy, recreational therapy, nursing, social work—then making sure that you’re meeting their needs at home.”

That kind of longitudinal care, says Jones, ensures continuity and a holistic approach to every survivor’s long-term health and well-being. “They’re patients with us for life,” he says.

A Team Effort Toward Healing

Brody, an energetic, sports-loving kid, had looked forward to a summer playing baseball with the North Polk Comets, a team coached by his dad. But now, bandaged head to toe in Iowa City, the baseball field seemed a million miles away.

In the days after the accident, Brody’s body was so swollen he was nearly unrecognizable. Severe damage to the skin—the body’s largest organ and its first line of defense—can trigger widespread inflammation and dangerous systemic problems, stripping away the natural barrier that retains fluids, regulates temperature, and protects against infection. To stabilize him, doctors worked quickly to replace fluids intravenously, a treatment that contributed to the dramatic swelling.

“They never stopped listening or caring or investigating what they could do for Brody.” Ashley Pearston

Burns also require specialized wound care, from complicated dressings that require frequent and painful changes, to daily hydrotherapy sessions, to delicate surgeries. With Jones leading the surgical team, Brody underwent two skin grafts that used healthy skin from his thighs and back to replace badly burned patches on his arms and legs.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

Brody spent 38 days in Iowa City before being released from the burn unit in July 2025.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY PEARSTON

Brody spent 38 days in Iowa City before being released from the burn unit in July 2025.

“There were just so many different pieces of the puzzle to getting him healed,” says Ashley Pearston. “The nutrition team, the infectious disease team, our nurses, our main surgeon, our pharmacist—they all played a huge role. They never stopped listening or caring or investigating what they could do for Brody.”

As Brody’s skin slowly healed, there were nights when the itching was so excruciating that he couldn’t sleep. Other times, he couldn’t stomach food. But his parents’ feelings of helplessness were eased by the care team.

“I don’t want to say it was manageable, because there were a lot of days that I felt like it wasn’t manageable,” Ashley says. “But it made it so much more of a team process. Rather than me just sitting in this corner in the hospital room watching them do everything, they were very open to how I advocated for Brody and what Brody’s needs were at the time.”

PHOTO: LIZ MARTIN/UI HEALTH CARE

Patient care technician Steven Hoff is pictured with nurse manager Jolyn Schneider outside the Burn Treatment Center. In 1992, Schneider was among the UI nurses who cared for Hoff as a child after he suffered severe burns from a campfire.

PHOTO: LIZ MARTIN/UI HEALTH CARE

Patient care technician Steven Hoff is pictured with nurse manager Jolyn Schneider outside the Burn Treatment Center. In 1992, Schneider was among the UI nurses who cared for Hoff as a child after he suffered severe burns from a campfire.

A Special Staff Connection

Nurse manager Jolyn Schneider (88BSN) and patient care technician Steven Hoff know firsthand what it’s like to be a child in the hospital—experiences that now guide their care for young patients like Brody at the Burn Treatment Center.

Schneider, who grew up in the small northeast Iowa town of Luxemburg, was hospitalized for long stretches as a child at UI Health Care and Mayo Clinic because of a rare skin condition called pustular psoriasis. Resembling burns it causes large, painful blisters with a high risk for infection. During weeks and monthslong stays, hospital staff became like family to her. She remembers chatting with the nurses on their breaks and going on rounds with doctors while wearing their lab coats. “I knew then that I wanted to do that for somebody someday,” says Schneider. “I remember from the time I was in second grade saying I wanted to be a nurse.”

Meanwhile, a horrific accident first brought Hoff to the UI in 1992. At age 2, he fell into a campfire at a campsite just south of Iowa City and suffered third-degree burns to his arms, neck, and face. His mother was told he might not survive—or, at best, lose his arms. Instead, Hoff underwent multiple surgeries, skin grafts, and years of physical therapy at Iowa. Though he lost the tips of two fingers, doctors ultimately restored function to his arms and hands.

Schneider was on a job shadow with burn specialists at UI Health Care early in her career when Hoff was rushed in that night. “I remember just watching all the teamwork and the people around this very little boy,” Schneider recalls. “I just remember thinking, ‘He has to be so scared, and he needs people to be with him.’”

Shortly after, Schneider accepted a job with the burn unit. Three decades later, she now leads a team of 47 nurses and 28 patient care technicians. That includes Hoff, who joined the staff in 2015. Like Schneider, Hoff wanted to give patients the same compassion he received as a patient. “I just had so many people taking care of me when I was younger, that’s what I wanted to do,” he says.

“When I was younger I felt easily ostracized. People would always stare at me. But through camp, I had opportunities to have people not just see me for my scars.” STEVEN HOFF on the annual Miracle Burn Camp

Hoff credits the Miracle Burn Camp—a summer program at Camp Foster on Lake Okoboji for young burn survivors—for helping him build confidence and a sense of purpose as a child. Hosted by the St. Florian Burn Foundation, a longtime partner with the UI Burn Treatment Center, the camp is staffed by professional firefighters, burn survivors, and burn care professionals. Between his time there as a camper, then as a counselor in his teens and early 20s, and later as a board member for the St. Florian Burn Foundation, Hoff spent nearly 25 years affiliated with Miracle Burn Camp.

“When I was younger, I felt easily ostracized,” says Hoff. “People would always stare at me. But through camp, I had opportunities to have people not just see me for my scars; they just treated me like a normal person. That’s probably one of the reasons why I really love it up on the burn unit. I’m not looked at as a former patient, as a guy with scars. They’re just like, ‘Hey there, Steve.’”

Hoff is grateful for the perspective he has as a burn survivor, which gives him compassion and understanding for his patients. “I wouldn’t change anything, because it’s who I am,” says Hoff. “And I wouldn’t have met all these great people, had these great opportunities.”

Treatment for burn patients has dramatically changed since Hoff was a child. Thanks to strides made in critical care and new therapies, burn centers nationally now see a 97.7% survival rate for admissions, according to the American Burn Association. Among those innovations used at Iowa is ReCell, a treatment in which doctors harvest a small sample of the patient’s skin, isolate the cells crucial for regeneration, and spray them back over the burned area to regrow skin. Another approach, known as cultured epithelial autograft, also starts with a small skin sample—but this one is sent to a laboratory, where new sheets of skin are grown and later applied to the patient’s injuries.

Just as crucial as cutting-edge therapies, says Schneider, is Iowa’s family-centered approach to care that places a patient’s loved ones as partners in the healing process. Family members are invited into decisions, valued for their insights, and supported as part of the care team.

“A burn injury truly involves healing from multiple levels,” says Schneider. “It involves healing from a nutritional level, a mobility level, but also very much so a mental and spiritual level. Especially patients with really devastating injuries; they’re not the same person they were before the injury, and you have to help the family cope with that as well.”

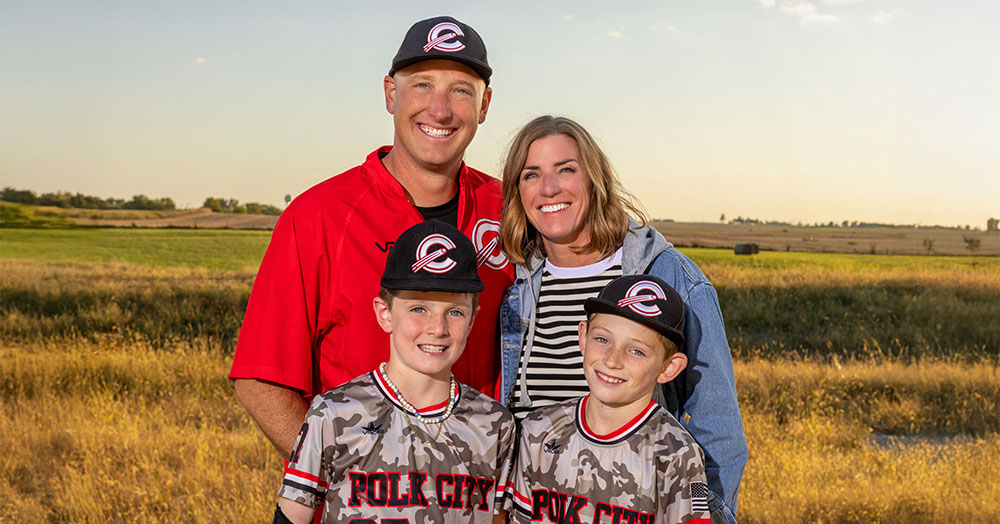

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Durk and Ashley Pearston with their children Brody and Knox

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Durk and Ashley Pearston with their children Brody and Knox

Rounding the Bases Home

For weeks, Brody Pearston fought to heal. His hospital room filled up with toys, stuffed animals, and get-well signs from his baseball teammates. New Iowa men’s basketball coach Ben McCollum visited and left a signed ball. Each day, Jones would greet Brody on his rounds with a smile and ask, “How’re we doing today, my man?” Back home in Polk City, the community printed “Brody Strong” T-shirts, with the proceeds going to the Burn Treatment Center.

“These people have become like family to us.” Ashley Pearston

Even the smallest movements were intensely painful, yet Brody’s rehabilitation depended on him eventually returning to his feet. The center’s physical therapy team devised games to get him moving—tying a ball to a string for him to hit with a bat and scattering “Brody Bucks” around the unit for him to collect on walks. He spent his Brody Bucks on a stuffed koala with a remote control that made comical noises, which he loved placing outside his door to scare the nurses. One night, he and a nurse toilet-papered the physical therapy office. The next morning, Brody woke up to find the PTs had TPed his room.

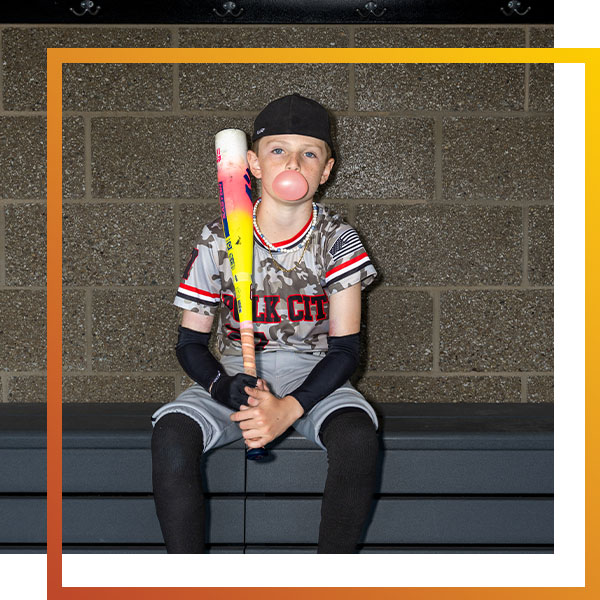

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Brody returned to his youth baseball team this fall following his release from the hospital.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Brody returned to his youth baseball team this fall following his release from the hospital.

Five weeks after the accident, Brody was released from the hospital. Doctors and nurses signed one of Brody’s teddy bears before saying goodbye. On the foot, Jones wrote: “I will miss you, my man!”

“It was one of those sad, joyful moments,” says Ashley. “These people have become like family to us, and now we’re leaving them. We prayed for that day for so long, but it was a little scary, really, because there were so many more unknowns about what it would be like at home.”

Brody continued to make progress in Polk City. Ashley and Durk administered antibiotics through an IV push daily, diligently tended to his bandages, and moisturized his skin.

At a follow-up visit in August, Brody was cleared to swim, play flag football, and best of all, rejoin his baseball team.

The day Brody returned to the diamond, his parents wiped away tears when he ran to first base on his own—no Brody Bucks required.

He was back with his old team, thanks to his new team in Iowa City.