An Iowa-Trained Photographer Finds Zen in Alaska’s Volcanic Ruins

ALL PHOTOS: GARY FREEBURG

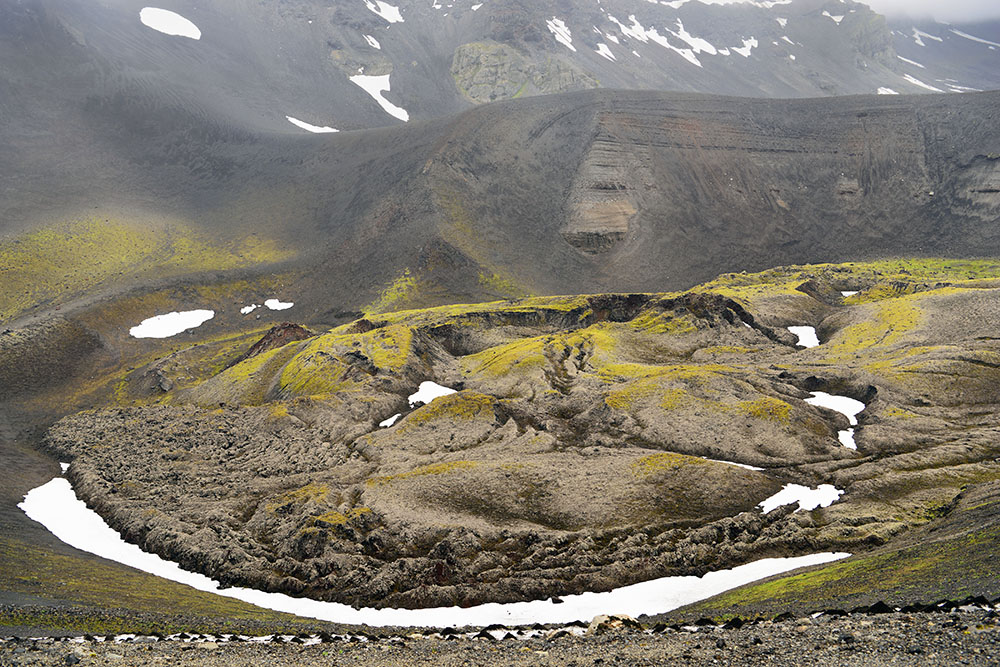

View of the north crater rim of Aniakchak volcano, which last erupted in May 1931

ALL PHOTOS: GARY FREEBURG

View of the north crater rim of Aniakchak volcano, which last erupted in May 1931

In 1912, a series of violent volcanic eruptions rattled a remote river valley on the Alaska Peninsula. The ejection lasted for 60 hours, spewing 30 times more magma than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington. The Alaska event, which is known as the largest eruption of the 20th century, buried a 44-square-mile valley in ash and pumice.

PHOTO COURTESY OF J.T. THOMAS

Landscape photographer and Iowa art graduate Gary Freeburg

PHOTO COURTESY OF J.T. THOMAS

Landscape photographer and Iowa art graduate Gary Freeburg

For decades, steam billowed out of the valley’s ash-covered floor, giving the area its popular name: The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

While the smokes have largely extinguished, other scars of this cataclysm remain more than a century later. The valley is pockmarked by craters and littered with volcanic rocks that resemble reptilian scales. Other areas are as stark as the surface of a distant moon. Vegetation is nonexistent.

Many would view the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes as a wasteland. Gary Freeburg (78MFA) sees serenity. The renowned landscape photographer, who captures the craggy expanse in shades of black and white, often compares the area to a Zen dry garden. To him, traversing this volcanic valley is an immersive experience in tranquility.

“In the Buddhist dry gardens, you’re sitting on the outside looking in at them because you can’t walk around in the garden itself,” says Freeburg, a graduate of the UI School of Art, Art History, and Design. “But in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, everything is scattered all around you. You’re actually standing in the garden. And to me, it’s a peaceful, wonderful place to be.”

Vent Mountain, located within the Aniakchak Caldera on the Alaska Peninsula

Vent Mountain, located within the Aniakchak Caldera on the Alaska Peninsula

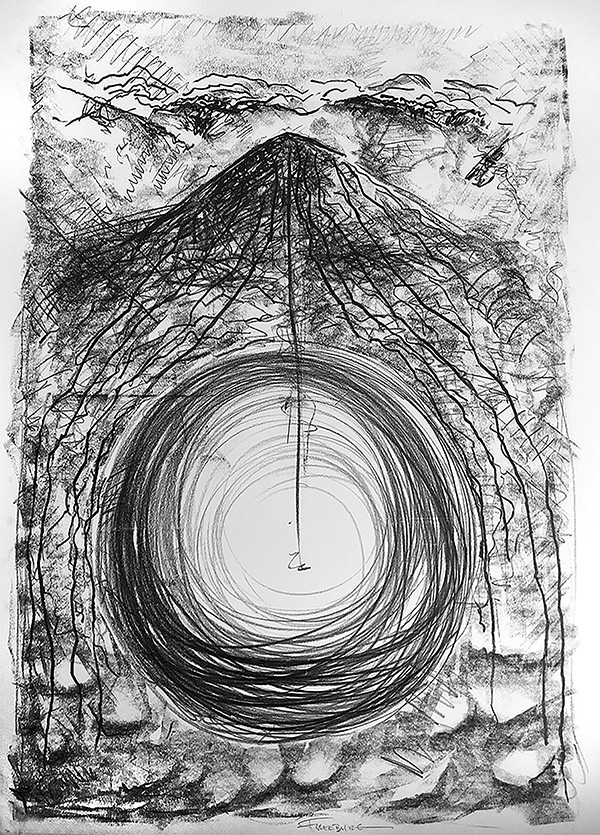

Freeburg spent 25 years living and teaching in Alaska. Although he now resides in Maine, the 77-year-old continues to venture back to the Alaskan frontier; this past July, he spent weeks camping inside a remote volcanic caldera. His work—which includes thousands of photographs in both black-and-white and color, lively sketches, and multiple books—documents the constellation of volcanoes that dot the Alaska Peninsula, which sits at the collision point of two massive tectonic plates.

Photographing the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes for the first time in 2000 was among the highlights of his artistic career. But his interest in the Alaskan wilderness began decades before he had heard of the volcanic valley and years before the 49th state was officially admitted to the union.

It began when he was 13, sitting on a boat with his grandfather in his native Minnesota. The fish weren’t biting. So, to pass the time, his grandfather took out his billfold. Freeburg expected him to hand him a dollar. Instead, his grandfather removed a picture that had been clipped out of an issue of National Geographic. The photograph depicted Denali, then known as Mount McKinley, North America’s highest peak.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Freeburg was transfixed by the image. “It showed me the gravity of a photograph,” he says. “That photograph is still stuck in my mind, just as fresh as it was that day.” He can still remember the composition of the shot—the mountain’s snow-capped summit rising above a lake fringed with verdant forests.

The distant territory’s rugged wilderness captured the imagination of grandfather and grandson alike. Freeburg recalls his grandfather telling him, “I’m never going to have a chance to see this place, but I hope that one day you’ll go there and see it for yourself.”

Freeburg finally reached Alaska in 1980. In the preceding years, Freeburg served in the United States Navy and spent nearly two years in Vietnam. He then received a pair of degrees in photography from Minnesota State University before attending the UI for a Master of Fine Arts, studying photography under longtime professor John Schulze (48MFA). After graduating from Iowa in 1978, he returned home to Minneapolis to operate a studio. But Alaska beckoned, and he realized it was time to embark on a new adventure.

When he first arrived in southeast Alaska for a part-time teaching gig in Sitka, he immediately fell in love with the location, which was nestled between the Pacific Ocean and soaring mountain peaks and devoid of the muggy conditions of summertime in Minnesota. “I took one big breath of air, and I knew this is home to me,” he says.

After his stint in Sitka, Freeburg accepted a position as an art professor at Kenai Peninsula College, an extension of the University of Alaska Anchorage. He ended up teaching at the college for most of his time in Alaska. The campus art gallery now bears his name.

“I took one big breath of air, and I knew this is home to me.” —Gary Freeburg

Freeburg enjoyed Alaska’s natural beauty. But his camera was more drawn to documenting how these environments change, not only as conditions freeze and thaw but as the Earth moved underneath his feet. “There’s a lot of action up there like volcanoes and earthquakes, which really appealed to me,” says Freeburg.

His first subject was the dynamic coastlines of Sitka, which were constantly changing with the tides. As the waters retreated to the sea, natural compositions of volcanic rocks and swirling sands were left in their wake.

These shots reminded Freeburg of something he had seen during his deployment in Asia. In Vietnam, everything was overwhelming—the noise, the energy. Freeburg escaped the fray while on leave in Japan and discovered relief in the meticulously raked sands and carefully positioned rocks in a Zen dry garden. As he watched, the sand seemed to ripple around the rocks, like a tide ebbing along a shoreline.

Freeburg attempted to recreate a similar sense of serenity in his photographs of tide pools and rocky shorelines. The resulting work formed the basis of his first photography exhibition in southeast Alaska, which caught the eye of the National Park Service. Several park rangers that attended the show thought Freeburg’s photographs of the Alaskan coast invoked a remote region completely shaped by volcanic activity: the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

In June 1912, an emerging volcano known as Novarupta began spewing ash as high as 20 miles into the sky. The eruption buried a 40-mile swath of the surrounding Ukak River valley in smoldering ash. The layer of ash was as thick as 700 feet in some areas, creating a landscape largely devoid of life.

Adding to the area’s otherworldly aura was the constant smoke wafting up from the valley’s floor. The ash preserved heat for decades, and any water that was buried by the initial eruption or percolated inside the deluge was superheated into steam. The steam escaped from the ash through vents known as fumaroles that dotted the landscape like chimneys.

The scene captivated the botanist Robert Fiske Griggs, who conducted the first scientific survey of the volcanic valley for the National Geographic Society in 1916. “The whole valley as far as the eye could reach was full of hundreds, no thousands—literally, tens of thousands—of smokes curling up,” Griggs would later write. “Some were sending up columns of steam which rose a thousand feet before dissolving.”

Griggs’ account inspired others to begin referring to the area as the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. While most of the steaming fumaroles have died out as the ash cooled, signs of the eruption are evident throughout the valley. Novarupta’s lava dome pokes out of the valley floor like a giant, coal-colored bubble. The valley is also littered with volcanic bombs—masses of molten lava as large as boulders that were ejected from the erupting volcano and cooled as they traveled across the Alaskan sky.

“The whole valley as far as the eye could reach was full of hundreds, no thousands—literally, tens of thousands—of smokes curling up.” —BOTANIST ROBERT FISKE GRIGGS, WHO INSPIRED THE NAME FOR THE VALLEY OF TEN THOUSAND SMOKES

The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes is located within a remote swath of Katmai National Park and Preserve. When workers at the park mentioned the valley to Freeburg, he was immediately intrigued by the area’s evocative name. He knew he had to see it for himself.

However, reaching the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes was no easy feat. The journey entails a flight from Anchorage to a small village called King Salmon. Then comes a seaplane flight to the Brooks Camp region of the national park, an area famed for its population of brown bears. From there, it is a 23-mile drive through all terrain before a lengthy hike. The first time Freeburg made the trek in 2000 he carried 125 rolls of film with him as he hiked some 12 miles through the bush.

The views of the valley were worth the trip. Freeburg was immediately struck by how the area was largely devoid of plant life, which brought the details of the volcanic landscape into focus. “Foliage tends to soften the environment, and you lose the starkness of just the object by itself,” he says. “That contrast is what I’m always looking for.”

A 1912 volcanic eruption created this field of pumice-covered snow pyramids near the Knife Creek Glaciers within the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes at Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska.

A 1912 volcanic eruption created this field of pumice-covered snow pyramids near the Knife Creek Glaciers within the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes at Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska.

Freeburg visited the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes five times between 2000 and 2011. In recent years he has set his sights on Aniakchak Caldera, a national monument further down the Alaska Peninsula and part of the Aleutian Arc.

The Aniakchak volcano once stood about 7,000 feet tall. But an eruption 3,500 years ago caused the summit to collapse, creating a caldera that spans some six miles across. The area has experienced roughly 20 eruptions since its collapse. Features from these subsequent eruptions, like cinder cones and volcanic bombs, litter the caldera’s floor.

Aniakchak’s most recent eruption occurred in 1931. Over a span of six weeks, magma gurgled out of the caldera as earthquakes rocked the region. The eruption carved new craters and buried much of the caldera in ash. Local life was devastated.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Capturing how life recovered at this caldera fascinated Freeburg. However, reaching Aniakchak is just as difficult as reaching the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. The journey culminates with a seaplane ride through a notch in the caldera’s rim before landing on a lake. This requires a good deal of luck with the weather. And Aniakchak’s location between the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea often creates a tempestuous mix. “Sometimes, it’s like looking into a bowl of oyster stew, because it’s completely packed in with clouds,” says Freeburg.

This past July, the weather cooperated enough for his fourth visit to Aniakchak. But conditions were far from nice. The wind whipped, and the rain was incessant. Freeburg still managed to snap 200 photographs, documenting how the local environment had changed since his last trip in 2018.

Some of the changes were subtle, like lichens inching across volcanic rocks. Others were substantial. Unlike the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, life has bloomed in many areas of Aniakchak after the 1931 eruption. The caldera contains Surprise Lake, a spring-fed body of water that is surrounded by a carpet of hardy tundra vegetation including mosses, grasses, and small shrubs. This tundra is home to Kodiak brown bears, caribou, and squirrels. During one trip, Freeburg struck up a friendship with a fox that frequented his campsite.

The local climate has also changed in the 90 years since Aniakchak last erupted. Some glaciers hanging from the southeast side of the caldera have almost completely disappeared, and the amount of snow has decreased in recent years. In the past when Freeburg visited Aniakchak during the summer solstice in June, he would often wake up surrounded by snow in a tent encrusted with frost. But this past summer, the temperature was relatively balmy, hovering within the 40s the entire time. Aniakchak’s environmental flux makes the caldera an ideal subject for Freeburg’s lens. Freeburg is often asked why he does not frequent volcanic hotspots closer to home like Iceland. It’s because he has little interest in photographing active or recent eruptions. What appeals to him is the landscape long after the lava has cooled. “I like to go in and watch how these new Earth surfaces change over a period of time,” he says.

The Gates, Aniakchak Volcano

The Gates, Aniakchak Volcano

In 2005, Freeburg left Alaska and moved to Harrisonburg, a college town nestled in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. He served as an art professor at James Madison University and directed the school’s gallery of fine art before retiring from teaching in 2018 and moving to Maine.

However, Freeburg is not done trekking through Alaska. “I may live in Maine right now, but I always think of Alaska as my home,” he says. “I always have a plan to go back out there.”

In the next few years, he hopes to photograph several sites further out on the Aleutian Island chain, including the Pavlof Volcano, a snow-capped peak that ranks among the United States’ most active volcanoes in recent decades.

In the meantime, Freeburg has plenty to keep him busy at home. He estimates that he has several thousand negatives and digital prints, as well as hundreds of drawings, to review and organize from his expeditions. Sifting through all this material could keep Freeburg busy for the rest of his life.

But staying busy has always been Freeburg’s MO. Even though he no longer teaches, he does not consider himself retired. Former mentor and famed landscape photographer Ansel Adams told him that retirement was unacceptable for an artist. This outlook continues to drive Freeburg back into the Alaskan wilderness to photograph more volcanoes.

“I don’t consider myself to be old,” Freeburg says. “As long as I can climb around in a volcano, I’ll be happy.”

Jack Tamisiea is a science writer based in Washington, D.C., who covers natural history. Tamisiea’s work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine, and many others. Tamisiea is also the son of Iowa alumnus John Tamisiea (87BBA) and grew up an avid Hawkeye fan.