Robert Gallery on CTE, Depression, and the Psychedelic Therapy That Saved His Life

Robert Gallery (03BA) could have said nothing. The larger-than-life Iowa football legend, whose name and No. 78 are permanently affixed to the Kinnick Stadium press box, could have shoved aside the darkest details of his post-career mental health struggles. This was a small theater full of 100 strangers, after all—faculty and residents from the University of Iowa Department of Psychiatry, scribbling notes and listening intently while nibbling on deli sandwiches from a boxed lunch.

But on this late-fall afternoon, at the hospital across the street from where the 6-foot-7 inch, 325-pound lineman known as “The Mountain” built his football mythology, Gallery bared all. He spoke of his sweat-filled nightmares where he imagined putting a gun in his mouth, then woke up with a metallic taste on his tongue. He talked about morning jogs in his Northern California neighborhood when he thought about throwing himself in front of a semi. Or the high-speed, teetering out-of-control motorcycle rides where he pondered veering into oncoming traffic.

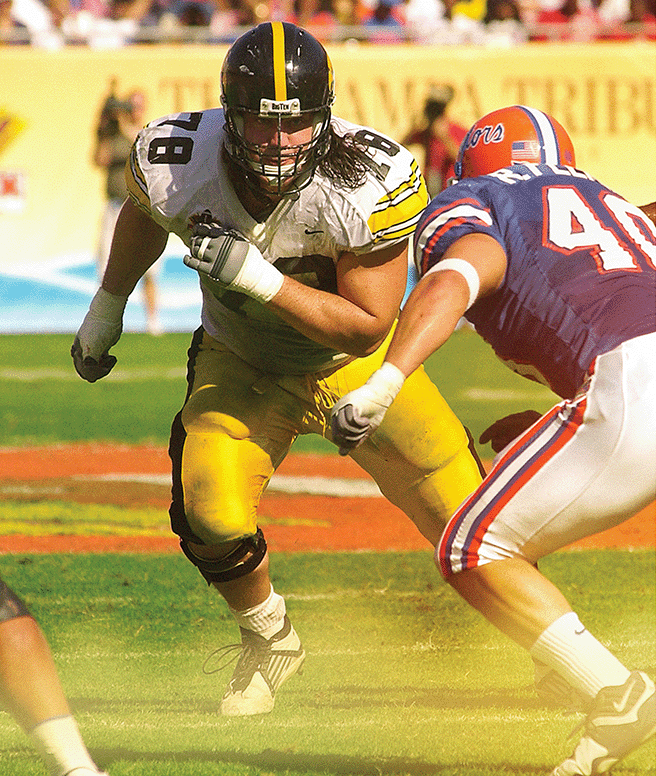

PHOTO: HAWKEYESPORTS.COM

Hawkeye great Robert Gallery’s dominance on the gridiron masked an inner struggle fueled by his drive for perfection.

PHOTO: HAWKEYESPORTS.COM

Hawkeye great Robert Gallery’s dominance on the gridiron masked an inner struggle fueled by his drive for perfection.

“To make it look like an accident,” said Gallery. “So nobody could say I quit.”

A lifetime of banging skulls with other 300-pound men had led to multiple concussions and troubling brain fog. Internally Gallery fought the war between the way the outside world perceived him—menacing, violent, relentless—and the way he often felt inside: inferior, inadequate, and insecure. The 2004 No. 2 overall pick in the NFL Draft struggled to equate the promise and potential of his franchise-altering selection with an eight-year NFL career that culminated without a Pro Bowl or playoff appearance.

Retirement made things even worse, with violent outbursts and erratic behavior creating an anxiety-fueled, walking-on-thin-ice atmosphere for Gallery’s wife and their three children. Spill the milk; make noise; look, say, or do the wrong thing; and Gallery would snap like a wire stretched too far.

“Then I would get angry at myself for not knowing why I was so angry,” Gallery explained to the audience that day. “I felt like such a failure. And that turned into ‘[my family] would be better off with me not here.’”

Becca McCann Gallery (04BA), the former Iowa women’s basketball player who met Robert on her first day on campus in 1999 and later became his wife, sat in the back corner of the room. She didn’t need to hear the stories. She lived them, wrestling with the fear that each time her husband left the house he may never return.

“It was scary,” she said. “Very real and very scary.”

It was also the reason the Gallerys were here, welcomed by Peggy Nopoulos (85BS, 89MD, 93R, 94F), chair of the UI Department of Psychiatry. Nopoulos, who leads research on the healing powers of psychedelic medicine for the treatment of alcohol abuse and other mental health disorders, wanted her department to hear firsthand the role psychedelics played in helping to transform Gallery from someone who believed he would be better off dead to the man they saw before them that day. Nopoulos moderated the event, at one point asking a delicate but pointed question about Gallery’s lowest moment.

“ I FELT LIKE SUCH A FAILURE.”

“Did you ever attempt?” she asked Gallery.

Gallery paused. He looked to the floor. Nopoulos set her hand on his shoulder. “It’s OK. You’re in a safe space here,” she said. “I know I just touched on something.”

Gallery shifted in his chair, crossing then uncrossing his arms. He rubbed his right leg, the rising cuff of his olive-colored joggers revealing a mosaic of brightly colored tattoos. He looked up, his eyes now filled with tears.

“I was very close a couple of times,” he answered. “I did have a pistol in my lap. I thought it would make everything stop.”

Behind the Armor

On the football field, Gallery was the poster boy of toughness—an imposing, vicious NFL gladiator with dark brown hair that flowed out of his helmet and over the nameplate on the back of his jersey. His arms were covered in tattoos. And he took pride in the nicks and scuffs in his helmet and bends in his facemask.

“I tried to use my helmet as a weapon,” he says. “My goal was to make you so miserable that you didn’t want to play anymore so you would give up.”

But such ferocity comes with a price. Gallery had multiple concussions and more than 10 surgeries on his back, ankles, elbows, lower leg, and core. After being kicked in the head during one 2011 game in Seattle, Gallery headed to the wrong sideline before a teammate corrected him. He says he popped pain pills like candy and took a Toradol anti-inflammatory shot before most of his 104 NFL games.

“That was the mentality,” says Gallery, who grew up on his family’s farm near Masonville, Iowa. “I was the tough guy who would go through anything to be on the field.”

Gallery believes the first signs of his mental health struggles appeared his senior year at Iowa in 2003. That season, the Hawkeyes finished 10-3, and Gallery was a unanimous first-team All-American and winner of the Outland Trophy, given to the nation’s top lineman. Despite his on-field success, he spent much of the season fixated on a single play in the team’s Big Ten opener at Michigan State. Not the one everybody else couldn’t stop talking about, when Gallery chased down a Michigan State defender to save a touchdown after an Iowa interception. But the one in which he felt he failed to execute a proper blocking technique, and officials flagged him for a holding penalty.

“Here I am supposed to be the guy, the one everybody is talking about and looking at,” says Gallery. “And on that play, I made a mistake. One mistake out of probably 70 plays. And I couldn’t stop thinking about it.”

Later that season, Scott Pioli, then New England Patriots vice president of player personnel, visited Iowa City on a scouting trip and raved to Gallery about his dominant senior season. “You’re killing it,” Gallery recalled Pioli telling him. But the All-American wouldn’t have it, pointing out his penalty against the Spartans. Pioli told him to relax and handed him a business card before heading back to New England. Written on the back: the words “Lighten up, Francis,” a quote from the film Stripes.

“The crazy thing is that’s what the NFL wants,” says Gallery. “They want you to be maniacal about your mistakes, so you can be this force of nature for them. But there’s this fine line. I wanted to be perfect, but no one is perfect.”

Greatness became even more challenging when the Raiders selected him in the draft. After starring for an Iowa program built on stability, Gallery played for five head coaches in seven Oakland seasons.

PHOTO: HAWKEYESPORTS.COM

Honorary captain Robert Gallery greets fans at Iowa's football game against Michigan State in fall 2023 after being inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame earlier that year.

PHOTO: HAWKEYESPORTS.COM

Honorary captain Robert Gallery greets fans at Iowa's football game against Michigan State in fall 2023 after being inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame earlier that year.

In 2007, the Raiders shifted Gallery from tackle to guard, an unofficial demotion in NFL circles. He heard NFL analysts refer to him as a “bust.”

And one day, he came home to a note on his door imploring him and his family to move. Gallery didn’t play on a single winning team during his seven years in Oakland.

“I don’t care what people say; losing sucks,” says Gallery. “You don’t do it for the money. That doesn’t bring you joy. So I’m beating my head in for what?

“And what did we do after games when the times were rough? I’d go drink 40 beers with the offensive line. Everything was in excess.”

“I WAS JUST SO ANGRY. I WAS TURNING INTO A PERSON I DIDN'T WANT TO BE.”

Gallery’s agent eventually connected him with a sports psychologist. Gallery hated the stigma that came with needing help. At one point he talked to his therapist in the bathroom so no one would find out. As time went on, Gallery would find himself easily triggered.

After one frustrating loss, Robert and Becca were pulling out of the Oakland parking lot, fans booing and throwing beers at their car, when Becca turned on the radio to listen to music.

“I absolutely lost it,” says Gallery. “I was just so angry. I was turning into a person I didn’t want to be.”

When the Game Was Gone

On the day Gallery knew his NFL career was over, he walked into New England head coach Bill Belichick’s office and thanked him for the opportunity. Gallery had signed with the Patriots in spring 2012 in pursuit of postseason greatness. But during training camp, he quickly realized he didn’t have it anymore. He found himself hoping he would tear his Achilles or suffer another type of season-ending injury so the decision to retire could be made for him. But it didn’t happen.

He told Belichick that he didn’t want to waste his time and left. He packed up the house he had rented in New England and flew home to California. On the flight, he drank every drop of scotch the stewardess could find on the plane. “And I don’t even drink scotch,” he says.

Gallery’s mental health quickly spiraled without the structure of professional football in his life. His anger escalated. He snapped over the most innocent of things, like one dinner when Becca’s mom suggested they eat outside since the sun had come out. “I just had this rage, like, ‘How dare you change where we’re sitting?’” says Gallery. “And I remember her looking at me like, ‘What is wrong with him?’”

This is when the suicidal nightmares began. That led to a lack of sleep, which made his moods even more volatile. Then the suicidal ideations began popping up during the day.

“The Robert I knew in college was not the Robert I knew when he retired,” says Becca. “It was hard.

“I tiptoed around a lot. I tried to find out how I could help him without making him think that I was trying to help him. I didn’t want to take away from his self-confidence or make him feel like he was one of our kids.”

After one morning workout, Robert cracked. He told Becca he was a burden on the family. They would be better off without him. Becca couldn’t believe his words. She insisted what he was saying wasn’t true. He didn’t believe her. Robert called NFL Life Line, an independent and confidential resource for NFL players and their families in a mental health crisis. In a few days, they helped connect Gallery with a therapist. He was involved in a workman’s compensation claim against the league at the time and that led to a brain scan to learn more about his condition.

At the time, the NFL was going through a concussion crisis, with PBS releasing its documentary League of Denial, which criticized NFL leadership for its handling of brain-related injuries. But Gallery struggled to make the connection to his struggles.

“Did I beat my brain up playing? Did I beat my body up? Of course,” he says. “And I would do it again. But did I think that could turn me into that sort of person? Naïvely, no.”

Although Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) can’t be diagnosed definitively until postmortem, doctors looked at Gallery’s scans and all but told him he likely had the degenerative brain disease found in so many former football players. They showed Gallery a scan of what a normal, healthy brain looks like at his age. Then they showed the image of his brain.

“It was mangled,” he says. “Like a baseball bat had been taken to the front of it.”

The images sent Becca into tears. Robert laughed. As troubling as it may have seemed, Gallery’s takeaway was a positive one. He wasn’t crazy. He wasn’t mentally weak. This wasn’t his fault. Doctors told Gallery if he did nothing, his brain would continue to deteriorate, his symptoms would worsen, and he’d eventually become another statistic.

Gallery met with brain specialists. He participated in light therapy and purchased a hyperbaric chamber to stimulate brain growth. He took antidepressants to try to improve his mood swings. He spoke to therapists. But he still struggled and endured suicidal thoughts. He stopped drinking excessively but still relied on alcohol in social situations.

“For a good year and a half, I did pretty much anything they told me to do,” says Gallery. “It was exhausting. When you do all these things that aren’t working, you want to give up. And that’s where I was at.”

Hope came in the form of a podcast Gallery listened to on a drive from the Bay Area to Lake Tahoe in 2021. Former Navy SEAL and Southern Illinois quarterback Marcus Capone was Marcus Lutrell’s guest on Team Never Quit. In his interview, Capone opened up about his struggles with mental health since retiring from service in 2013. With each word Capone spoke, Gallery became more optimistic.

“He talked about … how he found healing,” says Gallery. “It sounded like it was me on the radio. I remember thinking, ‘I’ve got to talk to this guy.’”

Gallery pulled over and called Becca, imploring her to listen to the podcast immediately. He emailed Capone, assuming he’d never hear back. But the next day he did. Gallery and Capone talked for two hours, with Capone quickly grasping the seriousness of Gallery’s situation. He mentioned the success he and other former military personnel had with ibogaine psychedelic therapy treatments in Mexico.

Gallery knew nothing of ibogaine, the psychoactive compound that comes from the root bark of the iboga tree. Ibogaine has long been used for medicinal purposes in central Africa and in studies has shown promise for treating addiction. Many researchers believe it can foster the creation of new neurons, prompting a rewiring of the brain that helps with self-destructive behavior. But as a Schedule I controlled substance, it is currently illegal in the United States, prompting patients like Capone and Gallery to travel to Mexico, Brazil, or other countries for treatment.

Gallery spoke to Capone every day that week. He researched the treatment, speaking to others who had gone through it and the team in Mexico that facilitated the treatments. Capone offered Gallery the open spot he had with a group of veterans going to Mexico in three weeks. The group included Luttrell, the retired Navy SEAL who was the subject of the 2013 Hollywood film Lone Survivor. Gallery was in.

“If it would have been anyone else, I don’t know if I would have trusted them,” says Gallery. “But when this Navy SEAL ex-football player told me he’s saving guys, my intuition was to trust this guy.”

Becca was understandably hesitant. Gallery admits he didn’t care. He called his parents and told them his plan. He didn’t want their opinion but wanted them to know how he felt about them.

“I just want you to know I love you guys,” Gallery told them. “If I die during this or if something happens, I love you guys. But I have to try this. It’s my last resort.”

A Last Resort

The day before leaving for Mexico, Gallery flew to San Diego to meet Capone and the rest of the group. He sat on the front porch after his morning workout with Becca, exhausted. Exercise had become a test in how far he could push his body to take his mind off the noise inside his head. As he looked out over the brush on the horizon, he saw a group of dead trees. He began to cry.

“It was the picture of my life,” says Gallery.

Becca asked if he was scared of the upcoming trip. Gallery admitted that no, he feared something altogether different.

“What if it doesn’t work?” he asked. “Then what?”

Two days later, Gallery found himself in the back of an SUV rolling through the outskirts of Tijuana wondering what he had gotten into. Aside from the couple times he tried marijuana to cope with his mental struggles, he had never used recreational drugs. “The D.A.R.E. program worked on me,” he joked. Now he was in Mexico about to go on a psychedelic trip.

“I was scared I was gonna die,” he says.

Research has found that the biggest risk with ibogaine use is an increase in the likelihood of cardiac arrhythmias and even cardiac arrest. This was one of the reasons the FDA ended federal research on the drug in 1995. Ibogaine use can be grueling on the body, potentially lasting more than 24 hours while forcing patients to relive traumatic events of the past.

These were the reasons Gallery had to get all his medications, including antidepressants, out of his system before Mexico. As soon as Gallery arrived at the facility, a house just outside Tijuana, doctors drew blood, analyzed urine samples, and gave each patient an EKG to ensure their heart could handle the treatment. The group then held a burn ceremony, where each person wrote on a piece of paper what they wanted the medicine to take away from them. Then they threw the paper into a fire. Gallery wrote that he wanted the medicine to remove his anger and hatred for himself.

After ingesting the ibogaine in pill form, Gallery lay on the floor hooked up to an EKG. He fell asleep. When he woke up some 10 hours later, his body felt like it had played an NFL season. Everything hurt. He couldn’t walk, needing a wheelchair to use the bathroom. He was painfully nauseous, vomiting everywhere. But he didn’t sense any psychological changes. He felt the medicine in his body. He recognized something was “off,” but he didn’t immediately recall any life-altering hallucinations. As he listened to the others in the group share stories of their experience, he convinced himself the drug didn’t work on him.

“Just another thing I failed at,” says Gallery. “I was so pissed at myself.”

That night, as Gallery began to feel better, he started journaling, and gradually his experience came back to him. He recalled watching a stream of movie clips from his life fly past. He kept the good memories for himself and threw away the negative ones. Later that night, the group prepared for the second part of the treatment, inhaling the substance 5-MeO-DMT, a dried version of a venomous secretion from the Colorado River toad. Some researchers believe the substance helps with the reduction of depression, anxiety, and stress. Unlike the ibogaine treatment, which the group took collectively, 5-MeO-DMT was administered individually.

When it was Gallery’s turn, he made the sign of the cross, expressed love for his family, and inhaled. Upon his second inhalation, he had a vision of God, whom Gallery asked to send him to hell. As Gallery tells it, God replied that Gallery needed to talk to Becca. She then appeared in a calm, loving way. And Gallery says he felt peace.

“I remember just sitting there thinking, ‘I do belong here,’” says Gallery. “You can say it’s corny or whatever, but all this love came back.”

Gallery eventually peeled his eye mask off and walked to sit in the yard. The blades of grass against his skin felt unlike anything he could remember. He heard seagulls flying overhead and smelled the salt from the ocean. One prevailing thought raced through Gallery’s mind: He was so happy to be alive. He couldn’t wait to see Becca and the kids. He walked into the room where the rest of the group had gathered.

“I’m back, bitches,” he said.

Back to Life

Early the following morning, the SUV carrying Gallery and the rest of the cohort headed back to San Diego, where Becca waited in the same restaurant in which Gallery first met the group a few days earlier. Gallery smiled, gave her a huge hug, and told her he loved her.

“I remember her face was skeptical, like, ‘What did I get myself into?’” he says.

For the better part of four months, Gallery lived in the “pink cloud” of posttreatment euphoria. Nothing bothered him. But over time, normal life began getting under his skin. While his rage stayed under control, within a year-and-a-half he again felt depressed and believed his family would be better off without him.

When his parents came to visit that year, they told him how proud they were of his progress. Gallery responded, “If I f*** up and kill myself, it’s not your guys’ fault. You have been good parents.”

“That’s when they knew—and I knew—I was back to struggling,” he says.

Gallery and Luttrell returned to Mexico later that year for another round of treatment. This time, during Gallery’s 5-MeO-DMT session, he hallucinated that he killed himself on his motorcycle. He saw the impact his suicide had on his parents, kids, and Becca. In real life, Gallery began to vomit. As doctors cleared his throat, Gallery felt like he was undergoing chest compressions. Convinced he was dying, Gallery began to scream and yell. “I took it too far! I always take it too far!” he said. That’s when Luttrell came in, put his hand on Gallery’s chest, and told him he loved him.

“It sucked all this rage and hate out of me,” says Gallery. “It was so profound. And still, to this day, if I have a bad nightmare or something, that whole thing comes back. It rewired how my brain thinks about my love for my family. I know, no matter what happens to me, I’m better off being here for my family. They need me in their life.”

Gallery went back to Mexico for another round of treatment in 2024, “for growth, not survival,” he says. He has not been back since and hasn’t touched a drop of alcohol since his initial treatment in 2021.

“THIS LITERALLY SAVED MY LIFE.”

“His story is the fabric and foundation of the mental health stigma,” says Nopoulos, the UI psychiatry professor and researcher. “Because he is big and strong, there is this notion that he can’t have a mental illness. Or if he does, then he must be weak. It’s just a horrid narrative.”

In the time since Gallery underwent treatment, the ibogaine movement has grown. In early 2024, researchers at Stanford Medicine found that ibogaine safely led to improvements in depression, anxiety, and functioning among veterans with traumatic brain injuries. In June 2025, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed a bill approving $50 million in taxpayer funding for the “Texas Ibogaine Initiative,” creating a consortium of universities, hospitals, and drug developers to create clinical trials on the drug with the goal of FDA approval.

Because of the stigma surrounding psychedelics, Nopoulos understands there will be skeptics. She is currently leading a study about the impact of the psychedelic psilocybin on alcohol abuse.

“These are powerful drugs that change the connectivity of your brain and how it works,” says Nopoulos. “There are certainly people who will say, ‘That’s hooey,’ but the proof is in the pudding. This man objectively is dramatically better. The evidence shows this works. It’s the mechanism of how this works that we’re not certain about.”

Gallery started the foundation Athletes For Care with the goal of helping other athletes enduring similar challenges to consider ibogaine and other psychedelic treatments for their depression and mental health struggles. Athletes for Care has already helped more than 10 athletes receive treatment, including former teammates of Gallery’s.

“This literally saved my life,” says Gallery. ”And the more guys I talk to, the more I realize we need something like this. I truly believe this is my purpose. This is what I’m here to do.”

PHOTO: CALEB SAUNDERS

Hawkeyes Robert and Becca Gallery returned to Iowa this past fall to share their personal journey to mental health with students in the psychiatry and athletics departments.

PHOTO: CALEB SAUNDERS

Hawkeyes Robert and Becca Gallery returned to Iowa this past fall to share their personal journey to mental health with students in the psychiatry and athletics departments.

Grace and Discipline

For much of Gallery’s football career, he would spend the night before a game in the hallway of the team hotel, tracing his footwork and perfecting the steps he would need to protect his quarterback and bulldoze holes through the opposition.

Now his daily preparations begin before sunrise. His body knows 4 a.m. Within a few minutes, he submerges himself in a 35-degree cold tub. He follows that with 20 minutes of meditation and breathing exercises in front of a fireplace. By 5, Becca joins for a morning workout, still designed by Gallery’s former Iowa strength coach. From there, he’ll sit in the sun for 10-15 minutes before relaxing in his hyperbaric chamber for an hour.

On Gallery’s bathroom mirror is a folded piece of paper with a typed prayer he received from Luttrell. Gallery has memorized it. He closes his eyes, puts his hand over his heart, and quietly repeats to himself: “Lord Jesus Christ, king of the universe, on this day I command my mind, my body, and my soul into your hands. Please tell me where to go, what to do, who to see, and what to say.”

Beneath the short prayer, four additional reminders: “Have a soul without fear. Smile. Think of gratitude. Attack the day.”

“You can say it’s corny, but I’ve learned through this that if I want people to see and feel the good in me, then I’ve got to feel it myself,” he says. “That’s the energy I want to give out.”

He does the same thing before he goes to bed, visualizing the next day to calm his mind. If he feels triggered during the day, he goes back to his breathing techniques, like he did before he and Becca spoke to a group of Hawkeye student-athletes about the importance of mental health.

Ten years ago, speaking to a roomful of people would have been a nightmare. Anxiety and fear would have consumed him, pushing him to drink in hopes of “faking it.” But on this night, Gallery sat in his hotel room and executed his breathing exercises. He pushed aside his insecurities that no one would show up, calming his heart rate in a few minutes.

A little more than two hours later, in a meeting room at Carver-Hawkeye Arena, Gallery wrapped up his talk with Hawkeye student-athletes with one final message.

“Give each other grace,” he said. “You don’t know what they’re going through. … So be nice to each other. And be nice to yourself.”

Wayne Drehs (00BA) is a freelance writer and visiting associate professor of practice at the UI School of Journalism and Mass Communication. He previously spent 23 years as an Emmy-winning sports reporter for ESPN.