Painting Kurt Vonnegut: An Iowa Artist Celebrates a Workshop Legend

“If I should ever die, God forbid, let this be my epitaph: The only proof he needed for the existence of God was music.”—KV

When Paul Engle (32MA) invited Kurt Vonnegut to teach at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1965, Kurt was a former car salesman who had no college degree and held no prestige in the publishing world. I suppose he felt a bit out of place.

I was released from the Johnson County jail the evening of my 19th birthday and decided I should be a writer. By 19 I was neither an accomplished criminal nor a law-abiding citizen. Wherever I fell between the two equated to spending time in jail every so often. Upon my release I walked down to the Iowa River to figure out what direction I wanted to take my life. By sunrise I figured the only thing I’d loved in life was writing, and so that’s what I would do.

I walked back to my apartment and researched how to become a professional writer. Though I read constantly, I’d never taken academia seriously. In fact, I failed my senior year English class and hardly graduated high school. But while researching paths to making a living as a writer, I saw one route was to attend a graduate writing program. I read about the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, how it was the first and most prestigious writing program in the world. I saw that it was located along the Iowa River, on a hill directly above where I’d spent the night trying to figure out my life.

I spent the next 10 years writing furiously. I worked as a concrete finisher, a carpenter, a heavy equipment operator, a grave digger—most weeks I worked 50-60 hours. I wrote every evening. I wrote on lunch breaks. I kept notebooks with me always and set tools down every time an idea or a line of poetry came to me.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

The winter of 2019, I was hanging drywall with a remodeling crew. I was 29. We were refinishing an apartment complex across the street from the Johnson County jail. I got a call from Elizabeth Willis, who told me I’d been accepted into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I’d been accepted into the program with no associate degree or bachelor’s degree.

I enjoy telling people this because they often think I’m lying. It’s the truth. I entered into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate program with a high school diploma.

***

I am scraping carmine red paint over the entirety of this 30-by-30 canvas. The hope is that some sort of sense will come through before long. When Iowa Magazine asked if I would paint Kurt Vonnegut’s portrait, I said yes in a heartbeat. Kurt has been a hero of mine ever since I first read Slaughterhouse-Five. Sometimes creative writing students will ask my advice about writing a war story. I always tell them to stay steadfastly in realism, not to give the reader a reprieve in a surreal moment. I then tell them to read All Quiet on the Western Front, as it is the second-greatest war novel of all time. Then I tell them to read Slaughterhouse-Five, as it is the greatest war novel of all time and proves my rule for writing about war meaningless.

One thousand frogs are singing as they see fit beneath the stars at midnight. I stare at the canvas, lit by a spotlight I once used for eyeing imperfections when mudding drywall.

The river is black behind the forest just to the north of the house. I can almost hear the water move east beneath the thousand frogs. We moved to this house last June. I’m below a crabapple out back I’m trying to bring back from near death, tending closely to its arborly needs for nearly a year now.

“I paint you hoping to know you, as we’ve never said a word, not one, to one another.”

This place is nearly the middle of nowhere. There’s not much light pollution out here. I cut the spotlight. The canvas disappears. Further and further my eyes silt off into the night sky until constellations fall where the crabapple’s wilted spring petals may die in the weeks to come.

I turn the spotlight back on and stare into the carmine blotch before me. I grab a cigarette near my brushes on a wicker table. I’ve been quitting; instead of a baker’s dozen a day, I smoke one at any odd hour desire strikes most astonishingly.

I cut the spotlight again and let the stars overtake me and my cigarette.

It is midnight in April. This tree may bloom.

***

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Red Danielson has painted many Iowa Writers' Workshop luminaries since graduating with MFA from the UI in 2022.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Red Danielson has painted many Iowa Writers' Workshop luminaries since graduating with MFA from the UI in 2022.

I’ve ripped a page of Vonnegut’s novel Breakfast of Champions from the book and taped it near this portrait as I bring it to a sort of life. It is the page in which Kurt brilliantly offers:

To give an idea of the maturity of my illustrations for this book, here is my picture of an a--hole:

And what follows is a doodle of just that.

I paint a deep dacite red across Kurt’s head and neck. It will show through in the darkest portions of his features, where wisdom and time have creased his forehead, eyes, chin, and throat.

How’s about a bit of blue over your eye here, Kurt? You don’t know it yet, but I can’t help any of it. I am trying to contain a piece of you in this moment, pinned to this canvas. I throw the entire rainbow at you, and through all of these bends of light, I see you coming through. It is April, and the skies are darkened with rain. I paint you hoping to know you, as we’ve never said a word, not one, to one another.

***

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Poet and painter Red Danielson

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Poet and painter Red Danielson

The ditches all along this county road have filled with blue chicory, mimicking best they can, a morning sky.

It’s rained so much this spring the morels are coming up everywhere. I’ve found five pounds in my woods, my lawn, along the foundation of my house, even in my driveway. My friends Moore and Stonehouse are camping along the Iowa River. I am driving to join them.

The skies are grey as we whip downriver in Stonehouse’s jonboat. You can’t hear a thing but the motor and the wind. Then all the world goes still, and we climb up the bank at a good flat bit of land with elms and maples. The forest is wet and filled with the song of wrens. Then it’s back in the jonboat and the roar of the motor downriver. On one bank I find an oriole’s nest hanging above a marsh. Red-winged blackbirds trill back and forth from the cattails. A beech tree has died and fallen in on itself. Most of the tree lies rotted over the marsh. Seven feet of the beech’s trunk still stands. At the very crest of the trunk is a small hole where a woodpecker has made its home.

Stonehouse takes us to a bluff downriver. The forest is silent here. As we walk through the woods I see a single columbine, ghostly indigo beneath an oak tree. It sways gently in the wind. From the top of the bluff, you can see for miles. We’ve loaded our mesh bags with yellow and grey morels. I find a shed dropped by a 2-year-old buck. The forest has aged the antler the color of yellow morels. Back at the jonboat, Moore sees the antler in my belt. He says it’s been in the forest a very long time.

Come night I will carve designs across the entirety of the antler. I will drill a hole where it once connected to the skull of the buck, just above the right hemisphere of the brain, and I will place an iron rod I’ve bent and shaped as a palette knife. Kurt, I will scrape paint over many of your features with this very tool.

***

It is a Wednesday night. I’ve started a fire from the limbs of an old hickory tree I cut down last spring. Barred owls fight in the oak grove over the pond. Frogs sing in hopes of making love under the waning moon.

I bring the painting of Kurt out by the fire because I want the night to show me something inside of him I’ve yet to see.

The fire crackles, and the world passes through its prism. I’m hoping to realize the index of life purged within every single thing I come in contact with. Sometimes only the shape of desire can be seen, or a gesture which has left a color upon a thing enduring without hunger, prayer, or sleep. In these moments, I witness the truest color of all being.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Painter and poet Red Danielson is pictured in his studio shed in rural Wellman, Iowa.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Painter and poet Red Danielson is pictured in his studio shed in rural Wellman, Iowa.

I only want to explain how. For the artist to explain why is like standing under the stars at night and turning the porch light on.

I walk to the backyard and stand beneath the dark canopy of the ailing crabapple tree. Thousands of pale pink flowers hang over my head like an explosion stuck in time. A tree blooms, or it does not. Most everything just sort of happens.

***

The sun’s rays are, on occasion, a harmonic array of pinks and greens. These colors seem to be the bridges every flower petal and bird feather travel in the heart of their daydreams. It is late afternoon, and I am blazing across the county on a spare tire, driving east to pick up my son Vincent from daycare. The trees rip like lightning bolts across the reflection of a tanker truck driving just ahead of me. I see the entire world reflected in this aluminum tank. There it is right in front of me, all the world bound for 100 million miles of itself: rain, bones, blazing mornings, and weary deaths. I see everything but my own reflection.

On the south side of the road, I pass a few little Amish boys, all wearing cotton shirts and suspenders. They must be 5 or 6 years old. One holds his black jacket over his shoulder. He turns when he sees my truck. He throws his right hand in the air and flips me off. My god, what man, woman, or child can say they’ve been flipped the bird by an Amish child? I feel the incredible fire of luck burn through my veins.

***

It’s June, and most of the wildflowers have bloomed. Bullfrogs skrim deep vibratos beneath the stars. Fruit trees have felled every flower petal and begun to push their harvest into the world. I feel so far away from my life.

Kurt, I am painting the shadows over your forehead tonight, painting the shadows around your eyes, beneath your nose and jaw.

What is a shadow, Kurt? My shadow holds no human names or allegiance. It is simply the inheritance of what I refuse to see. It’s not patriotic, and it doesn’t give a damn about slogans. It’s feral. It’s old. And it’s mine whether I want it or not.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

The artist's worktable and tools of the trade.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

The artist's worktable and tools of the trade.

The shadow is a midnight, a time of transformation—the hour when the hero descends into the underworld. So it is with each of us: We must descend into the darkness trailing our figures where we have exiled our own returns; our solstice, our longest night. We must watch the suns go down, one by one, through the doorway of the shadow where the soul speaks in symbols, and the night sings of a deeper dawn.

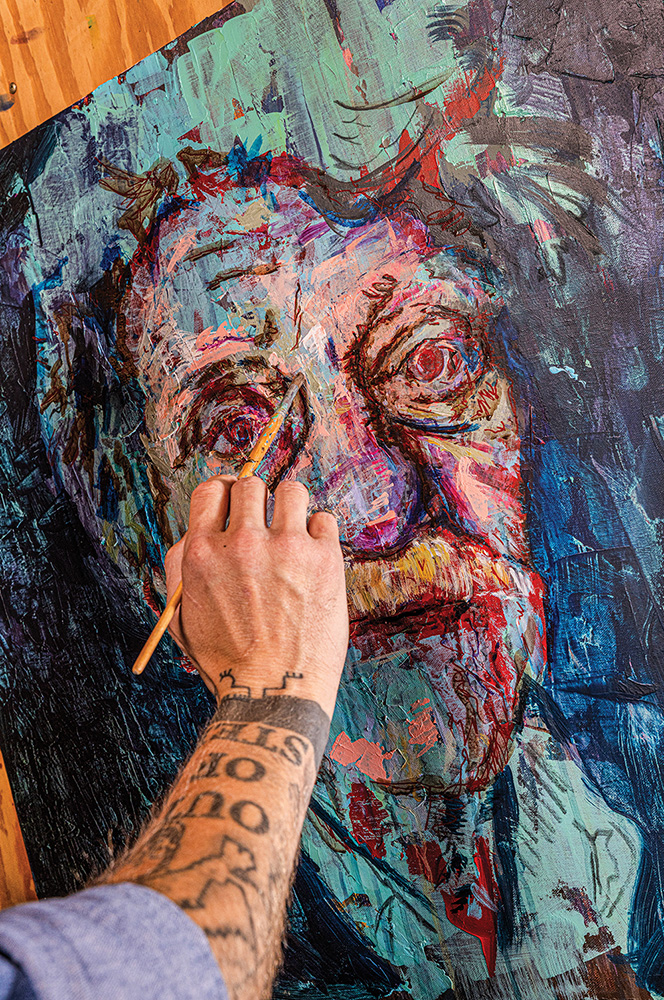

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Red Danielson adds layers of color to his portrait of Kurt Vonnegut.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

Red Danielson adds layers of color to his portrait of Kurt Vonnegut.

We find meaning in life from an incorruptible place—the wholeness that dwells at the center of the psyche. It calls to us from dreams, the still voice beneath the noise of personality. To hear it is to risk silence. If you ever hear it clearly, you’ll know.

I look into your shadows, Kurt. I am blessed by everything I see.

***

It’s the summer solstice, and I mowed part of the yard today. I like to leave parts of it unmowed and wild. My neighbor mows his lawn according to a pristine, cultivated doctrine. An unkempt lawn disturbs a very ancient thing in him he’s chalked up to virtue. I enjoy seeing him stare in contempt at bees coming and going from patches of dandelions as I lie in the depravity of my heathen daydreams.

“I look into your shadows, Kurt. I am blessed by everything I see.”

Solstice, from the Latin solstitium: when the sun seems to stand still. I sowed sunflower seeds around the northernmost perimeter of the garden in April. The sunflowers have grown tall under the heavy rains of spring. Two have just bloomed today. From the corner of my eye, I see them swaying in a gentle breeze. They seem to stand still when I stare directly into them. I walk around the house to the painting studio and squeeze some yellow ochre onto my palette. I ask Kurt if he loved sunflowers. I paint the yellow over Kurt’s forehead, his nose, eyes, and hair. The entirety of life is so pleasantly connected.

Kurt, the gods forbid many things, sometimes they even forbid life. A part of you is gone just now, but it’s rained so damn much these last few months, I’ve seen rainbow after rainbow. Maybe each time we die, the black space between double rainbows envelops us in infinite colors our living eyes will never know. Who knows.

I drove west today. The ash trees are bare all across the state. The emerald ash borer that thieved the emerald leaves from each of the trees must be evil in some way, but my god is it beautiful. I pulled the small notebook from the breast pocket of my shirt and made a note to put a bit of emerald in your hair, Kurt.

But now I paint beneath the black walnut in the southern acre of the house. It’s just me and the birds. Goddammit, Kurt Vonnegut, I wish you could hear them sing.