Cusp of History

Ferentz entered the 2025 season two wins away from surpassing Ohio State’s Woody Hayes as the Big Ten’s all-time winningest coach. Here are the top 10 coaches for wins while at a Big Ten school, as of the start of this season.

On an unseasonably warm December night in 1998, on the cement tarmac of the Eastern Iowa Airport, the white door of a private jet unfolded to unveil a 43-year-old man carrying a brown leather briefcase and the weight of a Big Ten university on his shoulders. He wore black slacks, a white button-up dress shirt, and a black and gold tie.

He wasn’t expected to be there. Eleven days earlier, 69-year-old Hayden Fry, Iowa’s all-time winningest coach, retired amid a quiet battle with prostate cancer. While Iowa fans fixated on other candidates—including former Hawkeye Bob Stoops (83BBA), who was quickly snatched up by Oklahoma—a steady leader emerged.

Kirk Ferentz was the assistant head coach of the Baltimore Ravens and a Fry pupil during an eight-year stint in Iowa City coaching the offensive line. His preparation, professionalism, and thoughtfulness wowed the search committee during an interview at a hotel near Cleveland’s Hopkins International Airport.

A day later, with his wife and young children by his side, Ferentz deboarded the plane prepared to write the next chapter of Iowa football. No one could have imagined what would happen next.

“Did I know at the time we hit a home run?” asks former Iowa athletic director Bob Bowlsby today. “That he would be at Iowa for 27 years? Hell no. And anybody who tells you otherwise is an abject liar.”

But even in Ferentz’s first hours on the job, Bowlsby found a coach who truly cared. Less than an hour after his plane landed, Ferentz addressed the Iowa team for the first time. His eyes filled with tears as he spoke.

“I remember standing there thinking, ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen, but we’re going to get every last ounce of effort out of this man,’” says Bowlsby. “You could sense the integrity. The work ethic. You could feel how much he cares. And that’s the way he has been all these years.”

Twenty-seven years, to be exact. Seven more than Fry—and counting. At age 70, Ferentz is the longest-tenured head coach in the country, and it’s been that way for nearly a decade. Sixty-nine coaches have been hired in the Big Ten during his Iowa tenure. He even outlasted the Sheraton Hotel in Cleveland where he impressed in his interview. That structure was torn down last fall.

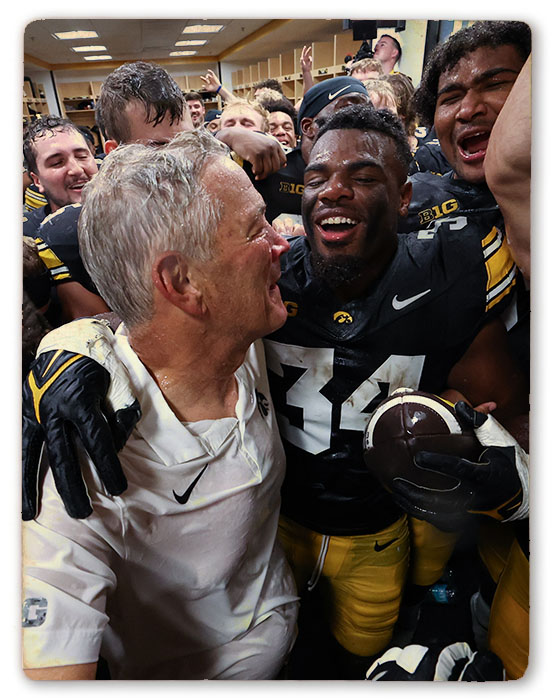

With Iowa's 47-7 win over Massachusetts on Sept. 13, Ferentz surpassed Ohio State’s Woody Hayes as the winningest coach in Big Ten history. His teams have qualified for a bowl game for 12 straight seasons, the seventh-longest streak in FBS. Iowa’s eight wins or more the last 10 seasons is a mark shared only with Alabama, Clemson, Georgia, and Ohio State.

But beyond the record-setting wins and gridiron legacy is the impact Ferentz has had on the young men he’s coached. Speak to enough of them, and you’ll see a common thread. Talk of family. Character. Toughness. And accountability.

These Hawkeyes can close their eyes and picture Ferentz on the elliptical or stationary bike in the Iowa football complex, an iPad in front of him scrolling through game film for the one advantage that might push Iowa on top. They can feel him at practice—stoic, silent, an eye on everything—until he sees something he doesn’t like, tosses his chewing gum to the side, and starts to teach. “Like some sort of mythical creature,” says former Hawkeye Dallas Clark (07BA).

There aren’t many secrets after 27 years. We’ve learned that Ferentz can get choked up after victories. He requires three packs of gum in his locker on game days. Ferentz almost always indulges in an ice cream cone the night before a game. And if he’s ever looking for something stronger, it’s probably a St. Pauli Girl lager. And if he can’t find that, a Heineken.

But none of those details account for the impact he’s had on the young men he’s helped raise. Details like never forgetting the name of a player’s mom or dad. (Or now, as many of his former players grow older, their children.) Ferentz has shown up unannounced at family funerals. He’s checked in on former players through their bosses or his NFL connections. And he’s done it all with a football family that only grows larger with each passing year.

“If you only look at the wins and losses, you’re missing the forest for the trees,” says former Iowa linebacker and Minnesota Vikings captain Chad Greenway (05BA). “The point of all this is to become a great human, citizen, husband, and dad. And I’ll tell you what—he has raised a hell of a lot of those over the years.”

“With the whole world spinning around him, he hasn’t changed,” adds former Iowa and NFL kicker Nate Kaeding (04BA, 15MBA). “It’s about character, developing young men as people, and this lifelong pursuit of continuous improvement. It’s such a special Iowa story that is uniquely ours, and we should continue to write and enjoy it as long as we can.”

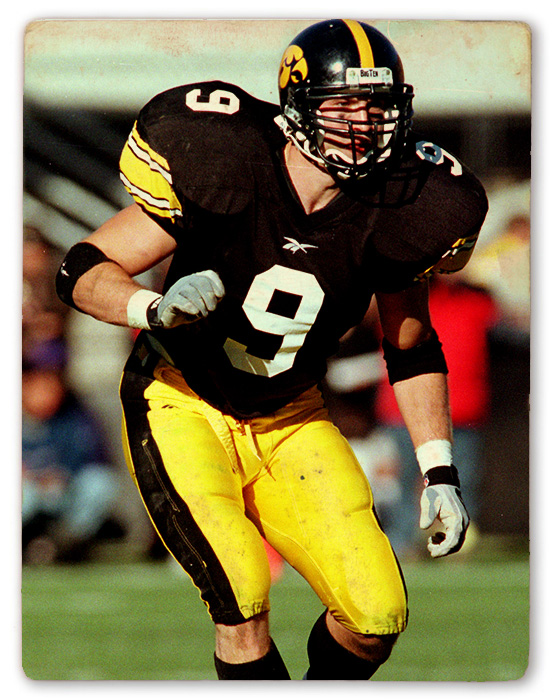

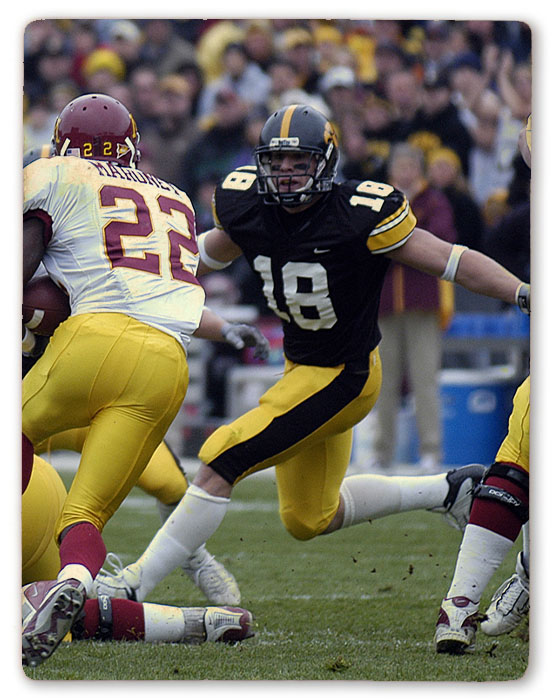

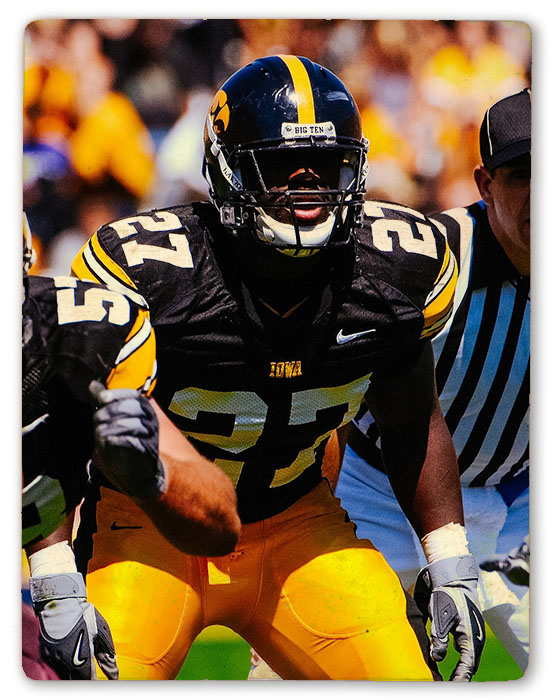

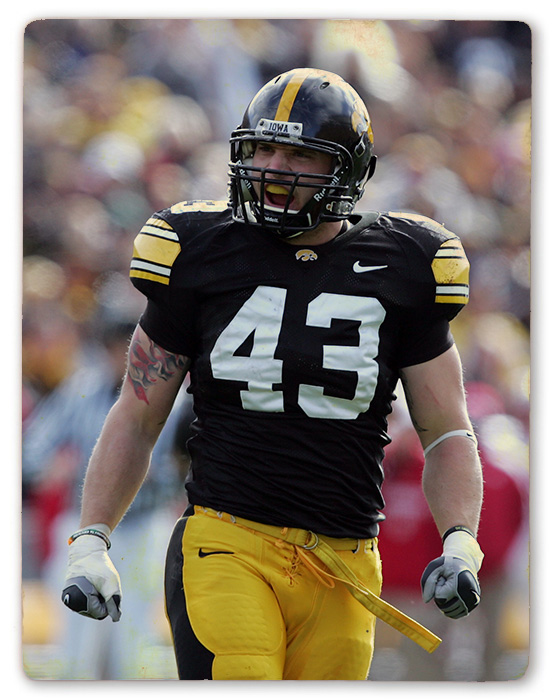

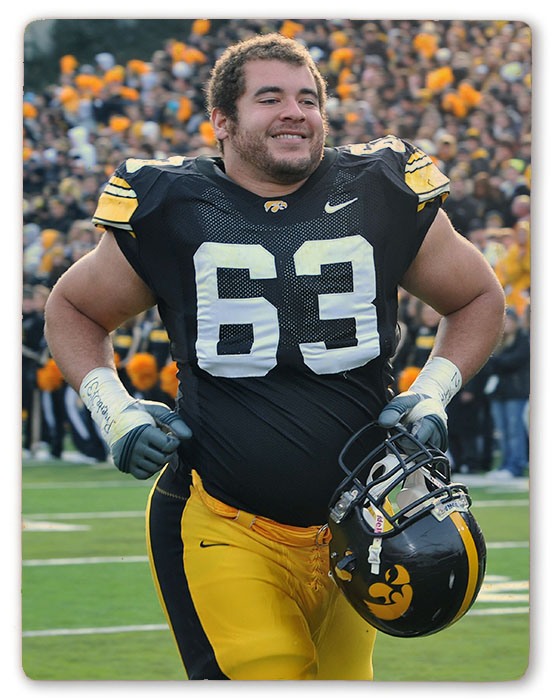

These are just a few of those stories that mean more than wins and losses, touchdowns and tackles, boosters and bowl games, from players who represent every year Ferentz has coached at Iowa. From Matt Bowen (99BA) and LeVar Woods (00BA) on Ferentz’s first team to recently graduated All-American linebacker Jay Higgins (24BA), here’s what Hawkeyes have learned from Ferentz, what he gave them in life, and what they try to give back to him, long after their Iowa City days are behind them.

Click to learn more!

1996–2000

Glen Ellyn, Illinois

1-10

ESPN NFL analyst, father of four

Shortly after Bowen’s NFL retirement in 2007, his wife, Shawn, gave birth to their first child, a boy named Matthew. He was born with Down syndrome. Bowen struggled with the reality of his new life.

“I did not do very well with it,” says Bowen. “I’m not proud of that, but I’m honest about it. It was hard for me to come to acceptance. There was so much fear and uncertainty as a first-time father with a child that has special needs.”

Bowen, who grew up in the Chicago area and returned there after his playing days, leaned on former Iowa defensive coordinator Norm Parker, whose son Jeffrey also had Down syndrome. That fall, as Iowa prepared to play at Northwestern, Ferentz invited Bowen, his wife, and 10-month-old Matthew to join the team dinner the night before the game.

“Come to dinner, sit with the coaches, and I want to meet Matthew,” Bowen recalls Ferentz telling him.

That night at dinner, Bowen watched as Ferentz and the rest of the coaching staff—including Norm Parker, Phil Parker, and Ken O’Keefe—all took turns holding and showing love for his little boy. Everything changed. On the drive home, Bowen’s wife told him he looked completely different—like a weight had been lifted. They still talk about that dinner today.

“I don’t know if I was looking for acceptance, but I needed that,” says Bowen. “And somehow, [Coach Ferentz] knew it. I needed to understand that I had been given a gift. Having Coach invite me, sit with us, and seeing him and everyone hold and play with Matthew, it was everything. It changed my life.”

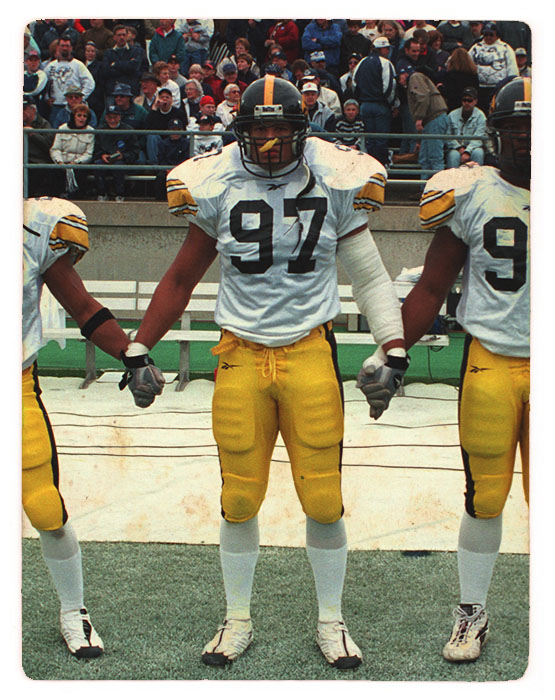

1997–2000

Alvord, Iowa

4-19

Iowa special teams coordinator, father of three

Woods played on Ferentz’s first Iowa team, then played seven NFL seasons before returning to Iowa City as an administrative assistant, interim assistant coach, and permanent assistant on Ferentz’s staff. Today he is the Hawkeyes’ special teams coordinator, one of the most respected assistant coaches in the country.

“These things are unheard of in this industry,” says Woods. “I never thought I’d be here for 18 years. Just like [Ferentz] never imagined he’d be here for 27.”

Woods was there in summer 2020, when a group of former players accused the program of racial insensitivity during the height of Black Lives Matter protests. To address the issue head-on, Ferentz sought the input of current and former players and made changes to the staff.

“We all had a chance to leave at the time,” says Woods. “I had questions. But he answered all of them. I felt more than comfortable staying. Then the work began looking within to fix things. We just talked it out, aired it out for months. Big groups, small groups. But that was really how we grew as a program.”

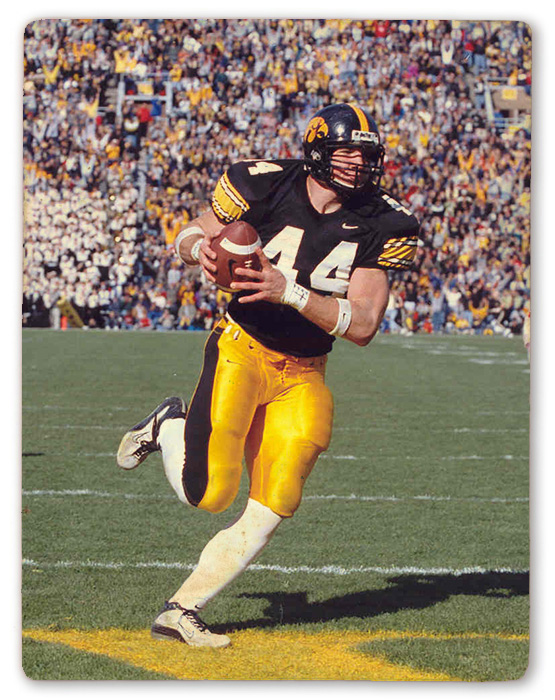

1999–2002

Livermore, Iowa

21-16

Organic farmer in Livermore, father of three

Even now, more than 20 years after playing at Iowa, Clark says thank you every time he sees Ferentz.

“There are people in your life that you just know God put there for a reason,” says Clark. “He’s one of them.”

Four days before Clark graduated high school, his mom died. In Iowa City, the walk-on linebacker leaned on his new coaches and teammates for support, with the goal of being a better linebacker than his older brother, Derrik, a third-team All-Big 12 performer at Iowa State.

“But I sucked at linebacker,” says Clark. “Coach Ferentz and [assistant coach] Bret Bielema (93BBA) had to be thinking, ‘What the hell is wrong with this kid?’”

After Clark’s freshman year, Ferentz proposed a move to tight end. He spoke to Clark’s dad and asked quarterback Kyle McCann (01BBA), one of Clark’s closest friends on the team, to help put the pressure on Clark to switch.

“I didn’t really want to do it, but I went to his office, sat on the couch and was just like, ‘OK, you win,’” says Clark. “Let’s do this.”

Clark worked with McCann the entire summer, thriving on the challenge of learning a new position. The payoff was becoming one of the greatest tight ends in Big Ten history, an 11-year NFL veteran, and a Super Bowl champion.

“I was a walk-on,” says Clark. “He could have just written me off, gone to bed, and focused on the 88 scholarship kids he had. But he didn’t. And I am forever indebted to him and so grateful.

“There’s nothing better than taking my kids to an Iowa football game and introducing them to Coach. I tell them, ‘I owe this man everything.’” he says. “They need to learn it takes great people to keep your life on track. And Coach is one of those people.”

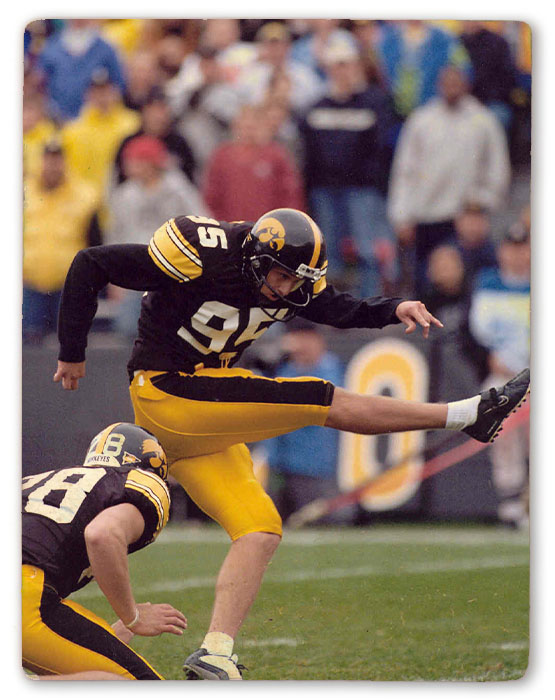

2000–03

Coralville

31-19

Iowa City entrepreneur, father of four

Kaeding was a member of Ferentz’s first recruiting class at Iowa, a scrawny kicker from Iowa City West High with big dreams but plenty to learn. Thrust into a starting role his freshman year, he missed eight out of 22 field goal attempts.

“It was a rocky ride,” says Kaeding. “Coach was always stern, but yet you always knew he had your back. At his core, he’s a teacher. He had a way of sprinkling in those compliments and the ability to give you confidence at the time when you needed someone to believe in you.”

That carried over to the NFL, where Kaeding experienced many highs and lows. During the regular season he was nearly automatic, twice earning Pro Bowl honors. He is still the 12th-most accurate kicker in NFL history. But Kaeding struggled in the postseason. After a critical miss, he’d return to his locker with a text from his former head coach.

“It wasn’t anything earth-shattering, but just the general sense of ‘Hey, we’re thinking about you. You’ve got a group of people here that love you as a person, whether you’re making 20 field goals in a row or missing five in a row,’” says Kaeding.

“In this day and age with social media, it can get really nasty and negative,” he says. “I can’t explain how important it is to know people like that always have your back. It just gives you that kind of armor. You’re sent out into the world knowing that you’re part of this tribe and that you have a leader in Kirk that, through thick and thin, no matter what, they’re always going to have your back.”

2002–05

Mount Vernon, South Dakota

38-12

Partner with Gray Duck Spirits, father of four

After a two-year battle with leukemia, Greenway’s father, Alan, died in December 2014, two days before Greenway’s Vikings lost to the Miami Dolphins in south Florida. Following the game, Greenway boarded a plane for South Dakota, where he attended his father’s funeral in his hometown of Mount Vernon, a map dot 85 miles northwest of Sioux Falls.

As Greenway walked into the tiny Salem Lutheran Church, one of two churches in the town of 449, he was stunned to find Ferentz and the entire Iowa staff waiting for him.

“Legitimately the first people in line at the wake,” says Greenway. “For him to care enough to take the time out of bowl preparation to fly up, you can’t fake that. He truly cares about us. He cares about your family. It’s genuine.”

Even now, after a decorated NFL career and having a family of his own, Greenway admits he is still nervous when he sees his former coach.

“It’s not like scared-of-him nervous, but I just respect him so much,” he says. “You stand up a little bit straighter. You don’t want to let him down.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t want to make him proud, in the same way that I wanted to make my dad proud.”

2003–06

Tallahassee, Florida

33-17

Coach at Cedar Rapids Jefferson High School, father of three

Even now, 20 years later, Miles can still hear Ferentz tearing into him after a series of blown plays during a 28-27 loss at Northwestern in 2005.

“His overall message was clear: ‘I’m sick and tired of seeing you play below your ability,’” recalls Miles. “’You’re better than this.’”

At the time, Miles didn’t care for Ferentz’s delivery. Nor was he thrilled earlier in his career when Ferentz called him to his office for not putting in the required eight hours a week with his teammates at study table. Miles said he preferred studying by himself at the library.

“He asked me, ‘What are the expectations?’” says Miles. “I said ‘Eight hours at study table, but …’. Then he stopped me. ‘Then you need to get eight hours at study table.’

“We had our run-ins. He would rip me. At that age, no one wants to be disciplined. No one wants to be held accountable. But as you grow older, you understand what it does for you. Now it all makes sense.”

Last fall, Miles returned to Kinnick Stadium as an honorary captain. And when he wondered about the possibility of coaching in college instead of high school, Ferentz warned him to prepare to miss a lot of family time.

“He’s a mentor you can always call on,” says Miles. “He helped me realize I’m not there yet. I enjoy spending time with my daughters, going to their dances. I enjoy spending time with my family. And then you start to think about all the things he’s missed to help all of us.”

2006–09

Bettendorf, Iowa

32-19

Hawkeye football radio analyst, business development officer, father of three

During summer 2008, when flooding along the Cedar River damaged an area greater than 10 square miles in Cedar Rapids, Angerer and other members of the football team’s leadership pitched in to help clean some of the 5,000-plus damaged homes.

At one point, a news crew showed up and asked to do a story on the football program helping those in need. Angerer watched as Ferentz politely asked the camera crew to focus its attention elsewhere.

“It would have been a great story—'Iowa football here to help,’” says Angerer. “But we weren’t there for that. And that’s him. There are so many things he does behind closed doors that nobody sees. People he helps get a raise. Donations he makes. He doesn’t care about publicity or attention. He does things for the right reasons.”

2006–10

Davenport

40-24

Executive director of Silvercrest Senior Living in Davenport, assistant high school football coach

Growing up less than an hour from Iowa City down I-80 in Davenport, Vandervelde admits he put Ferentz on a pedestal. So, on the day he and his parents sat in Ferentz’s office, he was so awestruck he didn’t even realize he had received an offer.

“He kept speaking, and the only conscious thing running through my head was, ‘Holy s---, it’s Kirk Ferentz. I’m in Kirk Ferentz’s office,’” says Vandervelde.

Vandervelde had a scholarship offer from Stanford at the time, but Iowa was his dream school. On the way home, Vandervelde’s mother turned to ask her son, “Is this really what you want?” He had no idea what she was talking about. His mom explained Ferentz had offered him a scholarship, and Vandervelde told the coach he needed to think about it. Vandervelde freaked. As soon as he returned home, he picked up the phone, called Ferentz, apologized for not understanding, and committed to the Hawkeyes.

“He’s so calm and measured with everything,” says Vandervelde. “I didn’t even pick up on the fact that this was the most exciting moment of my life.”

Now, nearly 20 years since that fateful day, with a brief stint in the NFL, plus time in the Scottish Highland Games and acting in local plays, he still admires his old coach.

“I know some people get older, and your coach becomes your buddy,” says Vandervelde. “I’m still intimidated walking into Iowa. There’s just this level of recognition there. He’s somebody I see as this font of wisdom. A mentor and man of prestige.”

2011–14

Buffalo Grove, Illinois

26-25

Strength and conditioning coordinator for the Chicago Cubs

The first time Weisman met Ferentz, he wanted to shake his hand, but he was holding two plastic bottles of protein shakes. Weisman immediately dropped the bottles to the floor. Thankfully, they didn’t explode.

“That was my first interaction with Coach,” says Weisman, an Air Force transfer. “Great start, huh?”

By the time he graduated, the Iowa walk-on would rank among the school’s career leaders in touchdowns and rushing yards. But more important were the lessons he learned off the field. Weisman purposefully took notes in every team meeting, not only with details on what he needed to know on the field, but his observations of Ferentz’s leadership style.

“Based on actions aligning with words, he’s the closest person there is to someone I want to be like,” says Weisman. “If he screws something up, he takes accountability for it. When things are going well, he gives credit to everyone else. When things are at their worst, he is the most calm.

“I want to be a father like him, a coach like him. I want to be able to handle difficult situations like him.”

After a brief attempt to make the NFL, Weisman, a health and human physiology major at Iowa, worked in medical equipment sales before reaching out to Ferentz about returning to Iowa City as a strength and conditioning intern. That turned into a job as a strength and conditioning assistant, which eventually led to working in the minor leagues of the Chicago Cubs organization.

After three years working with the Cubs, this past year he was promoted to head strength and conditioning coach for the major league team in Chicago.

“I’d be lying if I didn’t say he impacted my life in a major way where I was able to get that job,” says Weisman. “I can’t even pinpoint exactly what it is. It’s one of those things that’s ingrained in who I am now.”

2013–16

Detroit

35-18

NFL defensive back

His first year at Iowa, King started 12 of the team’s 13 games at cornerback, something no Iowa freshman had done in more than a decade. He earned third-team freshman All-American honors and seemed to have the brightest of football futures in front of him. But behind the scenes, things were not as great.

King struggled in the classroom. And as the team prepared for a New Year’s Day Outback Bowl clash with LSU, the university was close to putting King on academic probation. That’s when Ferentz called the Detroit native into his office.

“He was concerned,” says King. “Not about football, but about me. It was like disappointing your parents. He asked me why I was at the University of Iowa. What were my goals? And I had never really thought about any of that.

“I was on the verge of being released from the school. I had worked so hard to be there. And I was just giving it away. I wanted to be a captain. I wanted to play in the league. He helped me understand my purpose and how to become a man.”

That’s one of the reasons King postponed his NFL dreams for one more season and returned to Iowa his senior year to earn a degree. He’s since played eight years in the NFL as a defensive back and punt returner.

“That meeting changed the path that I was on, and I never looked back,” says King. “When I’m done playing, I want to continue his legacy and somehow give to others what he gave me, because that’s what it’s about.”

2014–18

Davenport

37-22

Realtor in Austin, Texas

Long before Gervase stepped on the field for the Hawkeyes, he learned about Ferentz’s character. Gervase was in high school when his grandfather, a longtime Hawkeye supporter, died. Ferentz showed up at the funeral.

A few years after the funeral, Gervase, a preferred walk-on, found himself at Iowa State’s Jack Trice Stadium, biting on a double move that resulted in a 74-yard go-ahead Cyclone touchdown with less than five minutes remaining. Iowa ended up winning the game in overtime, but the miscue sent Gervase, then a junior, to the bench.

During practice the next week, Gervase stood on the sidelines, waiting to get some reps with the second-string defense when Ferentz walked by.

“Keep going,” the coach told him. “You’ll be all right. Keep pushing. Keep fighting. Keep working.”

“That’s always stuck with me,” says Gervase. “He didn’t have to do that. He’s game-planning. He’s got 120 guys to worry about. But he could sense I was down and just took a little time to encourage me and give me some motivation. That’s Coach.”

Gervase eventually regained his starting role and three years later won a Super Bowl with the Los Angeles Rams. Afterward, Ferentz texted him congratulations.

“‘Hard work pays off.’ That’s what he wrote,” says Gervase. “It was so meaningful.”

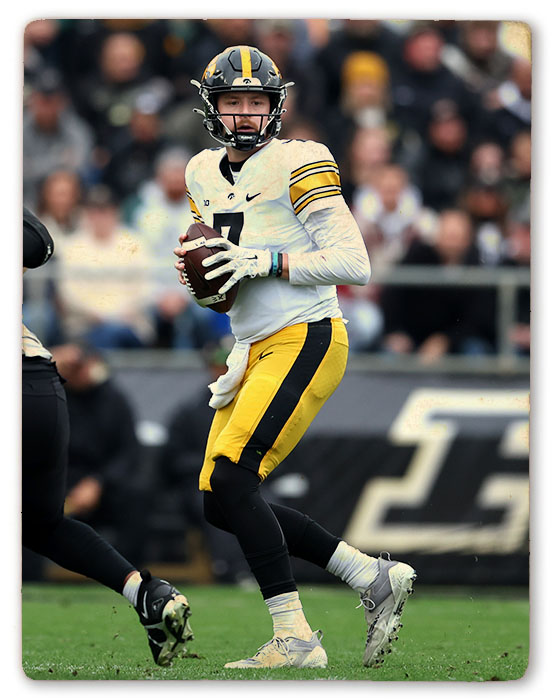

2018–23

San Rafael, California

43-18

NFL free agent quarterback

There are perhaps few players who understand the extent to which Ferentz backs his student-athletes better than Petras. Ferentz was there on the Kinnick sidelines when some fans booed and jeered the quarterback during a tumultuous time for the Iowa offense. But he never wavered on his support, even after Petras’ Hawkeye playing days were behind him.

“In every single situation, that man always does what’s best for his players, and, in a larger sense, his program,” says Petras. “He doesn’t care about anything except the people in the building. And he shows that to his players, maybe sometimes when people on the outside might think they don’t even deserve it.”

During his Senior Day start against Nebraska in 2022, Petras blew his shoulder out, a major factor in Iowa’s 24-17 loss. Petras had one year of eligibility left, but with an injured shoulder couldn’t enter the portal or the NFL draft. Ferentz proposed Petras work on the staff in a minimum-wage paid position that would allow him time to recover without losing his eligibility.

“It was his idea,” says Petras. “And I just don’t know many coaches that would have done that. Most programs would be, ‘You can’t help us on the field? Hit the road, Jack.’ He realized I needed more from him. And he didn’t hesitate."

Petras transferred for his final year of eligibility to Utah State, where he threw for a career-high 2,315 yards and 17 touchdowns. His Senior Day with the Aggies, he tore a ligament in the elbow of his throwing arm. He couldn’t attend the Hula Bowl or any other postseason scouting opportunities. Despite Petras spending a year away from the Hawkeye program, Iowa coaches invited him to throw at Iowa’s pro day, where NFL scouts gather to evaluate draft-eligible Iowa athletes.

When the quarterback elected to have Brian Wolf (02R, 06MS), the head of Iowa Sports Medicine, repair his elbow, Petras asked if he could train in the Iowa football facility during his recovery leading up to the pro day. The answer was “of course.”

“I thought I might get some looks, like ‘Why the hell is this kid back here?’ But nothing about it was weird or awkward or anything,” says Petras. “Everyone was awesome. And I believe that comes from Coach Ferentz. If you’ve done right by him, he’ll do right by you tenfold. There’s a reason anybody you talk to will die for that dude.”

2020–24

Indianapolis

42-20

Linebacker for the Baltimore Ravens

As a team captain for the Hawkeyes, Higgins grew to know Ferentz more deeply and become part of his trusted inner circle.

“He can’t talk the way he wants in front of everybody, but in that small group, you get to see the other side of him,” says the All-American linebacker. “How the only thing that matters to him are the people inside our building.”

Higgins realized this in person after Iowa’s 26-0 loss to Michigan in the 2023 Big Ten championship game. The linebacker sat next to Ferentz in stunned silence as the media peppered his mentor with questions about what they saw as a disappointing season without fully understanding all that had taken place behind the scenes.

“He took all the bullets for everyone else, like he’s John Wick,” says Higgins, referring to the Keanu Reeves movie character. “That’s a leader.”

Higgins believes that, in some ways, Ferentz has become a victim of his own success. The coach might not care, but some of his players do.

“He’s gotten so good at what he does that winning 10 games isn’t cool anymore,” says Higgins.

Higgins recently signed a rookie free agent contract with the Baltimore Ravens. He is the latest in a long line of overlooked Iowa prospects who will look to prove themselves at the next level. Lessons far beyond what they’ve learned on the field will push them the entire way.

“[Ferentz is] an example of what a person with power should act like,” says Higgins. “If you’ve played for him, you’ve seen what it’s like to have influence and eyes on you and how to behave and have true character in those situations.”

Wayne Drehs (00BA) is a freelance writer and visiting associate professor of practice at the UI School of Journalism and Mass Communication. He previously spent 23 years as an Emmy-winning sports reporter for ESPN.