Flyover State: Iowa Engineers Set Their Sights on the Future of Aviation

A 10,000-foot view of the University of Iowa reveals its breadth of research activity. From the Pappajohn Biomedical Discovery Building, where scientists search for cures to disease, to Van Allen Hall, where physicists study the stars, Iowa researchers speed toward scholarly and scientific breakthroughs.

For Tom “Mach” Schnell, that breakneck speed and bird’s-eye view of campus aren’t just figures of speech. The professor and test pilot soars over Iowa City in jets packed with experimental communication technology, artificial intelligence systems, and futuristic optical instruments. At a university known for excellence in research, Schnell’s laboratory in the clouds might be its most unique.

Schnell, an associate director for the UI’s Iowa Technology Institute and the Captain Jim “Max” Gross Chair in the UI College of Engineering, is the founder of the Operator Performance Laboratory. Since arriving in Iowa City 25 years ago this spring, Schnell has built the OPL into a nationally trusted aviation research hub. Today, he guides an 18-person crew of students and staff who operate a small fleet of aircraft and an array of flight simulators. Their research targets safety, efficiency, and human factors in the cockpit.

PHOTO: JUSTIN TORNER/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Professor Tom Schnell in the cockpit of a UI research jet.

PHOTO: JUSTIN TORNER/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Professor Tom Schnell in the cockpit of a UI research jet.

On a recent afternoon inside one of the OPL’s nondescript hangars at the Iowa City Municipal Airport, things are bustling. It’s a flight week, and Schnell and a team of engineers from Collins Aerospace are wiring prototype communications instruments inside 10-foot-long steel pods and attaching them, missile-like, under the wings of two UI research jets. Schnell and a fellow OPL pilot are scheduled to fly in unison to test the effectiveness of a directional data link developed by the Cedar Rapids-based defense contractor. If all goes as planned, the tech will securely relay live, 4K video between the cockpits of the planes and the ground team.

“The job of the airplane is pretty simple,” says Schnell. “The hard stuff happens here on the ground.”

The OPL’s main hangar is home to the UI’s three small research jets emblazoned with Herky the Hawk logos—two L-29 Delfins and an L-39ZA Albatros—and a pair of camouflaged MI-2 Hoplite turbine helicopters. Two nearby hangars house more airplanes—a Beechcraft Bonanza and a Cesna 172—and a stable of unmanned aircraft. A team of Collins Aerospace engineers huddles around a conference table near a wall of monitors. A giant American flag hangs from the rafters, and there’s a whiff of jet fuel in the air. If Maverick and Iceman wanted to go back to school for their PhDs, they’d feel at home here in Hangar H.

The focus this week is getting the Collins tech in the air for testing, but Iowa’s mid-December weather isn’t making things easy. Schnell checks his phone only to see more wind and snow flurries in the forecast. Months of work and planning for the Collins and OPL teams won’t mean much if the sky doesn’t clear up soon.

Although waiting out the weather is part of life for a pilot, Schnell isn’t one to sit idly by. There’s a reason he was assigned “Mach” as his call sign in his early days as a pilot. In German, mach schnell means “hurry up.”

Flight Path to Iowa

Schnell grew up near Bern, Switzerland, at the foot of the Bernese Alps. But mountain climbing and skiing held little allure for the young gearhead. “Harleys, muscle cars, Apollo moonshots—that kind of stuff really fascinated me. I think I was always an American born into a Swiss body,” Schnell says.

More than anything, Schnell loved airplanes.

Schnell’s parents bought him his first model plane kit when he was in grade school, but after the boy struggled to get it airborne, his father connected him with a local radio airplane club. The hobbyists, whose members included several engineers, took Schnell under their wing and taught him the basics of small-scale engines and aeronautics. Before there were drones, the club would send model planes equipped with an 8-millimeter camera over the mountains to capture panoramic films.

Schnell aspired to become a fighter pilot in the Swiss Air Force but was not selected. Instead, he worked as an apprentice at a telecommunications company as a teenager, then studied electrical engineering at the Bern University of Applied Sciences. Still, Schnell never gave up on his dreams of flying. He and his future wife moved to the U.S. so he could attend grad school at Ohio University, and he earned a fixed-wing pilot’s license and helicopter accreditation alongside a master’s and PhD in industrial engineering. Schnell’s early research was focused on highway safety, particularly how to make signage and roadway markings more visible to drivers. That work eventually led him to an assistant professorship at the UI in 1998.

“When I got out here, I asked where are all the university airplanes? They said there aren’t any,” Schnell recalls. With the backing of the department chair, the professor eventually scraped together grants to acquire the university’s first research plane, a single-engine Beechcraft A-36 Bonanza, and pivoted his academic focus largely from automobiles to aviation. Since then, the OPL has purchased and retrofitted three former military jets and two helicopters originally built in Eastern Europe during the Cold War (see sidebar) —relatively affordable aircraft on the used market built to last decades—to research how man and machine can work together in the skies.

“As far as a university, faculty-run laboratory, this is quite unique,” says Schnell. “We’re not focused on aerodynamics or making better airplanes. Our focus is really the stuff you put in them. In the digital world today, that’s everything.”

Small Crew, Big Impact

As part of the Iowa Technology Institute, the OPL puts next-generation tech through its paces for government agencies like NASA, the Federal Aviation Administration, and the Department of Defense, as well as for civil sector partners like Collins Aerospace, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin. Over the past two decades, Schnell has brought in $31 million in research funding and conducted more than 400 studies in areas like advanced navigation and sensors, autonomous systems, and artificial intelligence. With its relatively low-cost flight capabilities and host of sophisticated simulators, the small but nimble OPL team can assess emerging technology for a fraction of the time and cost.

“Our motto is to test early and test often,” says longtime OPL engineering coordinator Bradley Parker. “We can test ideas to see if they even pass muster, so you can save millions of dollars by not proceeding because it’s never going to pan out, or you can move forward if the fundamental ideas are great.”

The OPL has spearheaded a number of high-profile government studies over the decades. In a pivotal project in the early 2000s, Schnell’s team developed a synthetic vision system for NASA’s aviation safety program that depicts mountains and other hazardous terrain in low visibility conditions. Today, that Iowa-hatched tech is used widely in general aviation cockpits and can be found in thousands of planes around the world.

PHOTOS: THE OPERATOR PERFORMANCE LABORATORY AND JUSTIN TORNER/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Synthetic vision systems, AI-controlled jets, and advanced air-combat training systems are among the many forward-looking research projects conducted by the OPL.

PHOTOS: THE OPERATOR PERFORMANCE LABORATORY AND JUSTIN TORNER/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Synthetic vision systems, AI-controlled jets, and advanced air-combat training systems are among the many forward-looking research projects conducted by the OPL.

In recent years, the OPL has been evaluating artificial intelligence systems in fighter jets—an emerging area known as tactical autonomy. In an ongoing project, the OPL assesses how pilots and AI systems can work in tandem in dogfights, and how humans can learn to trust their AI counterparts to make critical decisions. In the future, the technology could allow pilots to serve as “battle managers” and direct squadrons of AI-flown fighter jets.

The OPL was also the first in the nation to test an advanced air combat training system being developed by Collins Aerospace for the U.S. Navy and Air Force that will transform how pilots prepare for war. The system allows real-life piloted jets to interact with digitally simulated enemies in warfighting scenarios. Instead of sending a half-dozen F-18s into the sky on Top Gun-like training missions, the new system—Tactical Combat Training System Increment II—allows a fighter plane to dogfight with synthetic adversaries, which appear as real enemies to the pilots on their cockpit displays.

“Without dropping bombs or shooting actual missiles, they can go out on a training range and learn the craft of aerial combat,” explains Schnell.

Engineering High-Flying Careers

The OPL’s longstanding ties to the Department of Defense make the UI an attractive destination for service members interested in aviation research. Schnell currently serves as academic adviser for two active-duty U.S. Air Force members, Major Kyle Smith and Major James Brown, who are pursuing PhDs in industrial and systems engineering while working as graduate research assistants alongside the OPL’s civilian team.

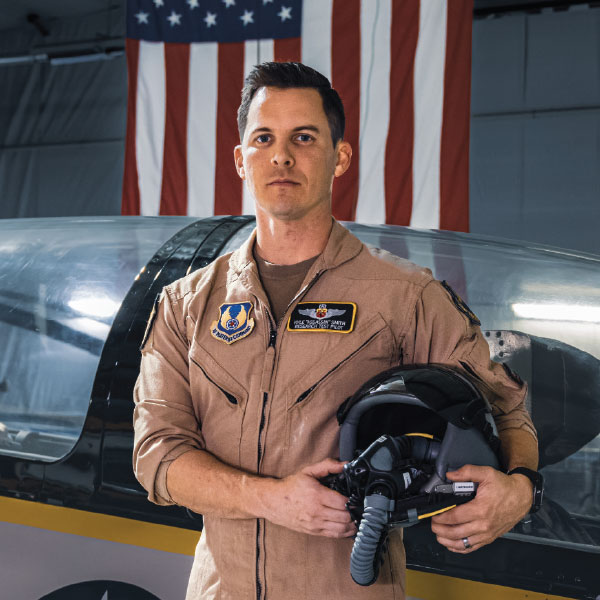

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

U.S. Air Force Major Kyle Smith is one of the latest active duty service members to work as a test pilot at the OPL. Smith is pursuing a PhD in industrial and systems engineering at the UI.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

U.S. Air Force Major Kyle Smith is one of the latest active duty service members to work as a test pilot at the OPL. Smith is pursuing a PhD in industrial and systems engineering at the UI.

Smith is a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School and has logged more than 1,300 hours piloting more than 30 aircraft, including 179 combat hours as part of Operation Inherent Resolve. He says the chance to help lead research on AI systems made Iowa the ideal fit to pursue his PhD.

“Autonomy is getting worked in more and more into our aircraft and our tactics, and it’s going to become an important part of the Air Force and for all the other branches,” says Smith, who earned a master’s at MIT. “We want to make sure that we get it right early on. And we want to get as much buy-in as possible from the pilots who are going to be allowing these things to fly them around, or who will be flying alongside totally unmanned aircraft.”

Dozens of accomplished Iowa engineering alumni earned their wings at the OPL before going on to high-caliber careers. Lockheed Martin, Collins Aerospace, the Federal Aviation Administration, and the Air Force are among the many landing spots around the nation for OPL graduates.

Schnell’s alumni roster includes Kyle Ellis (07BSE, 09MS, 14PhD), a deputy project manager at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. A mechanical engineering major while at Iowa, Ellis first heard about the OPL when he attended a freshman seminar led by Schnell. “I basically begged him for about a year after that to work in his lab,” says Ellis.

Schnell eventually found a spot on the payroll for Ellis washing planes and doing simple data collection projects. But soon, the undergrad was in the cockpit assisting pilots and training as a flight test engineer. Later, as a grad student at the OPL, Ellis worked on a NASA-funded project that turned into an internship and, ultimately, a career with the agency. Today, Ellis leads a team tasked with developing NASA’s advanced safety systems for aviation, creating the standards necessary for future generations of aircraft like drones and even flying cars to operate safely alongside existing technology.

“I developed a core understanding of how to design experiments and how to communicate those findings in that apprenticeship experience at the OPL,” Ellis says. “Being able to work in the industry from the very beginning was instrumental for my career. Tom has high standards and expectations and wants quality deliverables for things, so he will work with you to achieve that. But he also gives you space to learn and make mistakes, which is what an educational experience should be.”

Photos: THE OPERATOR PERFORMANCE LABORATORY AND justin torner/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

The OPL’s research team and its fleet of aircraft put next-generation aviation technology through its paces at its headquarters at the Iowa City Municipal Airport.

Photos: THE OPERATOR PERFORMANCE LABORATORY AND justin torner/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

The OPL’s research team and its fleet of aircraft put next-generation aviation technology through its paces at its headquarters at the Iowa City Municipal Airport.

A Lofty Laboratory

After three days of waiting out the weather to test the latest Collins Aerospace communications instruments, Schnell’s patience pays off. The morning fog dissolves into afternoon sun and a brief flight window at the Iowa City Municipal Airport. The OPL team rolls out two jets from Hangar H, and soon, Schnell and test pilot Aaron Williams, an Air National Guard veteran, throttle down the runway and skyward.

“It’s what I call the miracle of flight testing,” Schnell explains later. “You need funding. You need the weather to be good. You need the people to staff all the stations to be available. Then, you need the tech that you’re testing for the first time to actually work. You’re asking for a lot to line up.”

The pilots wing above eastern Iowa in a mile-wide tactical spread. Back in the hangar, OPL and Collins crews monitor the mission. The jets’ payloads—the cylindrical pods capped with 4K cameras and packed with radio equipment—do their job while the pilots perform a series of aerial maneuvers. The data link connects, and the two jets exchange real-time video feeds with each other and the ground team.

The exercise is the latest proof of concept for a Collins project commissioned by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency that would allow warfighters to precisely and securely transmit high-speed data through the skies. It’s another notch on the OPL’s nosecone of impactful research that could one day transform aviation technology.

Once again for Schnell and his team, it’s mission accomplished.