10 Moments When History and Iowa Football Collided

Regardless of how the Iowa football team fares on the field, this will be a season for the history books.

For the first time since 1889, when Iowa first played university sanctioned football, it appeared there would be no fall season. The Big Ten made the sobering decision in August to postpone all fall athletic competitions because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But then, a month later, the conference reversed course and approved an abbreviated campaign beginning Oct. 23-24 with new medical protocols in place.

This isn't the first time local, national, and world events have intersected with the gridiron. Here are 10 other moments when history and Hawkeye football collided.

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Fred

Becker, Iowa's first

All-American

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Fred

Becker, Iowa's first

All-American

1918: All-American Fred Becker killed in action in World War I

Before Nile Kinnick (40BA), there was Fred Becker. The Waterloo native was a standout lineman as a sophomore in 1916, when he became Iowa's first All-American. But he would never suit up for the team again. With the Great War embroiling Europe, Becker volunteered for military service in March 1917 and fought with the 5th Regiment of the U.S. Marine Corps. He was killed in action in July 1918 in France at the Battle of Chateau-Thierry. Becker posthumously earned the Distinguished Service Cross, the U.S.'s second-highest wartime award, and the Croix de Guerre, France's top honor for battlefield heroism.

1918: Deadly pandemic jeopardizes football season

Commonly known as the Spanish Flu, the pandemic of 1918—coupled with the war—caused many college football teams to forgo their seasons. An estimated 675,000 Americans died from the virus, including more than 6,000 Iowans. An outbreak hit the university that fall, filling University Hospital's isolation wards and ultimately killing 38 students and faculty members. On the football field, Iowa was among the teams that played on, despite large gatherings being banned across the state. Iowa's game at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, for instance, was closed to the public and played to a nearly empty stadium. Although players were in and out of the lineup with the flu, and the schedule was in flux for much of the season, Iowa finished with an admirable 6-2-1 record.

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Kinnick

Stadium, then known

as Iowa Stadium,

in 1930—the year

Iowa was briefly

suspended by the

Big Ten

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Kinnick

Stadium, then known

as Iowa Stadium,

in 1930—the year

Iowa was briefly

suspended by the

Big Ten

1930: During Great Depression, Iowa suspended from Big Ten

It was one of the bleakest periods of American history—and a dark time for Iowa athletics. At the onset of the Great Depression, the Western Intercollegiate Athletic Conference—better known as the Big Ten— suspended Iowa for a month in early 1930 because of what the conference deemed as "alumni interference" with the athletics program. Among other charges, it was discovered that a slush fund was used to provide loans and improper scholarships to student-athletes, though the practice was common at colleges and universities around the nation. The university cleaned house in its athletics department, and subsequently the university's football program sputtered for much of the 1930s as the state and nation sunk deeper into the economic depression.

1942: Navy Pre-Flight team shares Iowa Stadium with the Hawkeyes during World War II

After Pearl Harbor, facilities at many college and university campuses were swiftly converted into military training grounds to help the nation mobilize for war. The UI hosted a Navy Pre-Flight school from 1942 to 1945, and Quadrangle and Hillcrest residence halls served as temporary barracks while cadets trained in the Field House. Iowa Stadium was home to two football teams in those years—a UI program depleted by the war and the Navy Pre-Flight Seahawks. With military schools allowed to compete collegiately, the Seahawks—whose roster was filled with former college and NFL stars—were a force on the field. In three seasons, Iowa Pre-Flight posted a 26-5 record, twice beat the Hawkeyes, and finished in the AP Top Ten two times, including a No. 2 finish in 1943.

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

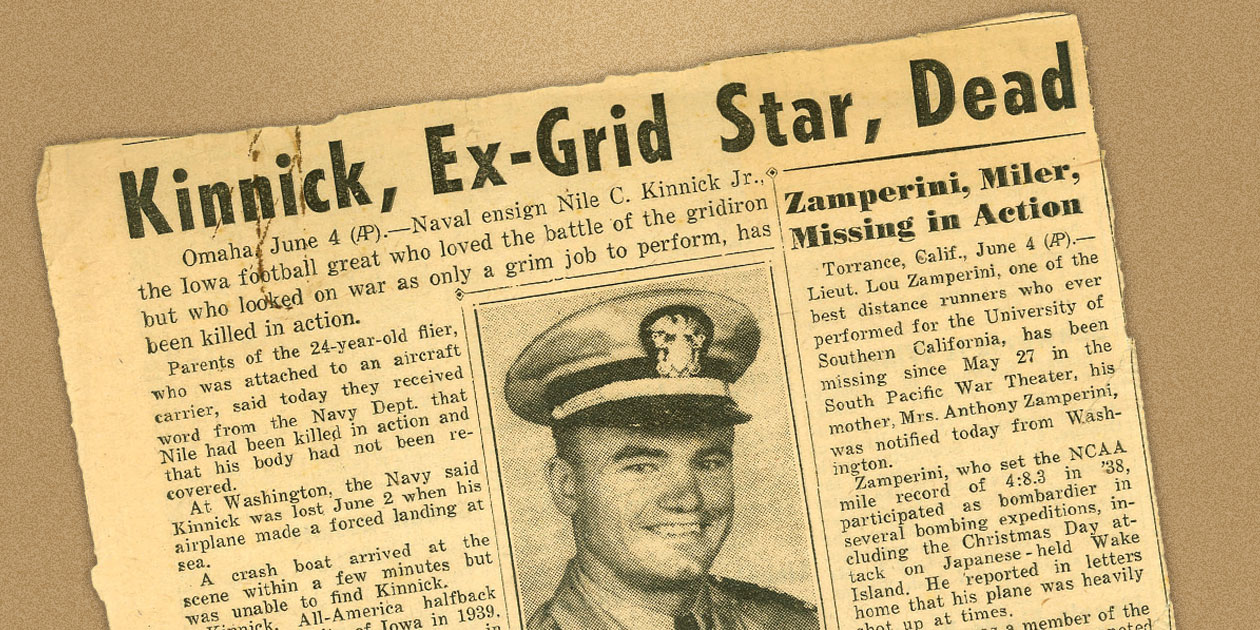

A newspaper

clipping following

the death of Nile

Kinnick

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

A newspaper

clipping following

the death of Nile

Kinnick

1943: Nile Kinnick dies in fighter plane crash during World War II

The life of Iowa's revered football and military hero came to a tragic end June 2, 1943, when the fighter plane he was piloting crashed on a training mission off the coast of Venezuela. Kinnick was 24—the same number he wore on the field while electrifying fans during the fabled Ironmen season of 1939. Kinnick won the Heisman Trophy that year, when he became a household name as a 5-foot-8 dynamo who dominated games on offense, defense, and special teams. Kinnick opted to pursue law school rather than professional football, but he put his scholarly ambitions on hold to serve his country in World War II. Today, Iowa's historic stadium bears his name, and his bronze statue greets fans at the south gates.

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Presidential

candidate John F.

Kennedy, alongside

Iowa Gov. Herschel

Loveless, visits

Iowa City in 1959; tickets to the 1963

Iowa-Notre Dame

football game

that was canceled

after Kennedy's

assassination

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Presidential

candidate John F.

Kennedy, alongside

Iowa Gov. Herschel

Loveless, visits

Iowa City in 1959; tickets to the 1963

Iowa-Notre Dame

football game

that was canceled

after Kennedy's

assassination

1963: Iowa's game with Notre Dame canceled following Kennedy assassination

The 1963 Hawkeyes, led by coach Jerry Burns, hoped to secure a winning season in their finale against Notre Dame. But the football game would never be played. On Nov. 22, 1963, less than 24 hours before kickoff, President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas. As the nation's shock turned to mourning, most college football games that weekend were canceled. That included the tilt in Iowa City, where four years earlier, Kennedy had stumped for the presidency. During that visit to the UI, he attended a Hawkeye football game against the Fighting Irish. "Someone said I should cheer for Iowa and pray for Notre Dame," Kennedy said that day.

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Coach Ray Nagel,

whose players

boycotted in 1969;

Dennis Green, a

member of the

1969 team

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Coach Ray Nagel,

whose players

boycotted in 1969;

Dennis Green, a

member of the

1969 team

1969: In turbulent era, Black players boycott team

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a volatile time on college campuses around the country. Sports were not immune from Vietnam War and civil rights tensions. The 1969 Iowa football season began in controversy when coach Ray Nagel suspended two Black players for disciplinary reasons. In response, 16 Black teammates, including running back and future NFL coach Dennis Green (71BS), walked out of spring practice to protest what they said was an "intolerable situation" for Black students and athletes at Iowa. After players with the Black Athletes Union and UI administrators worked for a resolution in the ensuing months, seven of 12 players who petitioned for reinstatement—including Green—rejoined the Hawkeyes that fall. The Hawkeyes went on to post a 5-5 record.

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

The

ANF helmet decal

added during the

1985 season

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

The

ANF helmet decal

added during the

1985 season

1985: Hayden Fry spreads ANF message during farm crisis

The 1980s were devastating for many Iowa farmers. As the nation's agricultural economy bottomed out, nearly 20,000 Iowa family farms went into bankruptcy. The hardship wasn't lost on Hayden Fry, the coach from rural Texas who felt a kinship with the state's farming community. With Iowa ranked No. 1 in the nation midway through the 1985 season, Fry planted a gold sticker with a simple message on his team's helmets to call attention to the farm crisis: ANF, short for America Needs Farmers. The Hawkeyes debuted the sticker during a nationally televised showdown at Ohio State, and it became a fixture on their helmets for years to come. Fry's successor, Kirk Ferentz, brought back the ANF emblem in the 2000s, and today the slogan lives on through UI athletics' partnership with the Iowa Farm Bureau.

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Iowa

plays Ohio State a

day after a campus

shooting in 1991

PHOTO: UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Iowa

plays Ohio State a

day after a campus

shooting in 1991

1991: Iowa defeats Ohio State day after tragic campus shooting

On Nov. 1, 1991, the unthinkable happened in Iowa City. A disgruntled graduate student opened fire inside Van Allen and Jessup halls, killing five people and leaving a sixth paralyzed, before killing himself. The gunman had intended to target Hunter Rawlings, but the UI president was in Columbus, Ohio, to attend a football game the following day. The game went on as scheduled that cold Saturday afternoon. Fry removed the Tigerhawk logo from the team's helmets, and Iowa upset Ohio State 16-9 behind a touchdown pass and run from quarterback Matt Rodgers (92BA). After the game, Fry said the emotional win was "for the people back home."

2001: Cy-Hawk game postponed in wake of 9/11 attacks

The sports world came to a standstill in the days after 9/11. Like Major League Baseball and the NFL, the NCAA canceled and rescheduled games following the terrorist attacks that scarred the nation. Iowa was scheduled to play rival Iowa State in Ames that Saturday. Instead, the game was moved to Nov. 24. After the postponement and an early-season bye week, Iowa returned to the field for the first time following 9/11 on Sept. 29 in Iowa City against Penn State. Giving fans a welcome diversion, the Hawkeyes defeated the Nittany Lions 24-18 behind two rushing touchdowns by Ladell Betts (01BS). The Cyclones won the rescheduled Cy-Hawk game 17-14 two months later, but Iowa finished 7-5 for its first winning season under Ferentz.