Famed Writers Cisneros, Harjo, Herrera Return for Iowa's LNACC Reunion

PHOTO: TEAGAN PERRIN/UI DIVISION OF STUDENT LIFE

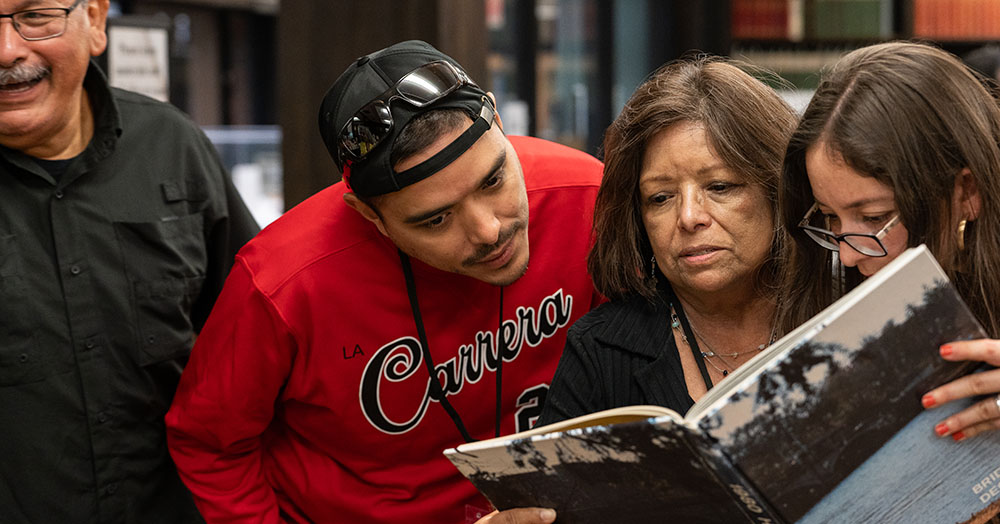

Longtime friends reconnect at the UI Latino Native American Cultural Center for a reunion in September that included storytelling sessions, a film screening, networking opportunities, and cultural gatherings of music, art, dance, and literature.

PHOTO: TEAGAN PERRIN/UI DIVISION OF STUDENT LIFE

Longtime friends reconnect at the UI Latino Native American Cultural Center for a reunion in September that included storytelling sessions, a film screening, networking opportunities, and cultural gatherings of music, art, dance, and literature.

The University of Iowa’s Latino Native American Cultural Center celebrated 50-plus years this fall with a Latino-Native American Alumni Alliance reunion headlined by the return of influential writers Joy Harjo (78MFA), Sandra Cisneros (78MFA), and Juan Felipe Herrera (90MFA).

The three Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduates joined event moderator and Ojibwe historian Brenda Child (83MA, 93PhD) and UI President Barbara Wilson for a panel discussion at the Iowa Memorial Union about their experiences as Latino and Native American students who found their home away from home at the cultural center, known as LNACC.

“[LNACC] is a great space for our students to come back, to be welcomed into a space where they feel safe, where they can learn about their heritage, and where they can meet each other,” said Wilson, noting students frequently bring up a sense of community when talking about their time at Iowa. “[Community is] a signature part of who we are.”

Harjo, a three-term U.S. poet laureate whose awards include the National Humanities Medal and National Endowment for the Arts and Guggenheim fellowships, shared that she applied to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for graduate school because of its reputation. “It was considered the best program in the country, and I think it still is,” said Harjo, a member of the Muscogee Nation who initially felt like an outsider on campus. “I already mapped out the Native communities, so I knew the Meskwaki weren’t too far away, but it was a big test for me to come into this place.”

She found community in the Chicano and Indian American Student Union, now known as LNACC, as well as in the company of fellow student Sandra Cisneros. Cisneros—whose honors include a National Book Award, National Medal of Arts Award, National Endowment for the Arts fellowships in poetry and fiction, and a MacArthur fellowship—says she was in awe of Harjo back then, because she could change a tire and drive a truck. Cisneros considered Harjo an older sister. “You’re the one who made me recognize my Indigenous self and took me to go to the Chicano center,” said Cisneros.

PHOTO: FRED EBONG

Acclaimed writer Sandra Cisneros speaks at the Latino Native American Cultural Center reunion about her first book, The House on Mango Street, which she began as a student at Iowa. The novel, which celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2024, has sold more than 6 million copies and become required reading in many schools across the country.

PHOTO: FRED EBONG

Acclaimed writer Sandra Cisneros speaks at the Latino Native American Cultural Center reunion about her first book, The House on Mango Street, which she began as a student at Iowa. The novel, which celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2024, has sold more than 6 million copies and become required reading in many schools across the country.

Finding the workshop culture of the time challenging, Cisneros gathered inspiration from everything else Iowa had to offer: performances at Hancher Auditorium, concerts at the art museum, and dance classes. Those profound experiences informed her writing and helped her move in a positive direction.

Cisneros’ debut novel, The House on Mango Street, which she started writing at Iowa, is now celebrating its 40th anniversary. “I’m grateful for the difficult time I had in Iowa,” said Cisneros, citing anger at being dismissed by workshop professors as the catalyst for writing a story only she could write. “I’m glad I didn’t quit. The book was my life raft.”

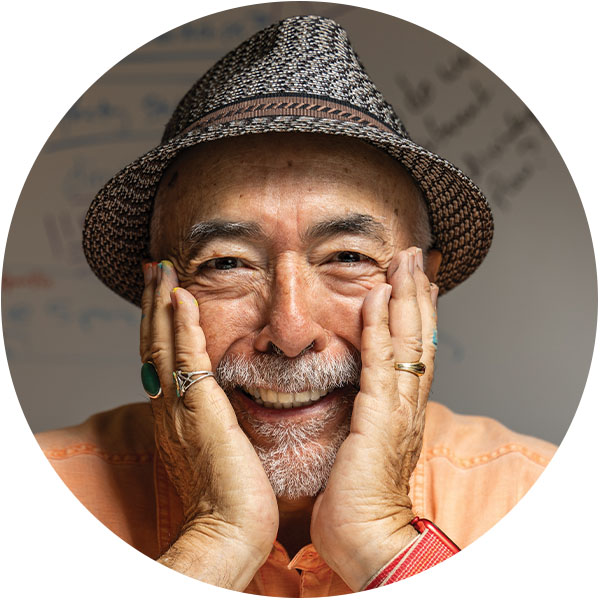

Herrera, a 2024 MacArthur fellow and a past U.S. poet laureate and National Humanities Medal recipient, started his tenure at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop while living in a house on Johnson Street in Iowa City. A good cook, Herrera soon became known for his tamales, which caught the attention of workshop faculty. “One day, the writers’ workshop said, ‘Can we have a party at your house? Can we have those tamales?’” Herrera recalled. “We had a great time cooking and eating some solid food.”

Herrera credits his mother for his creative voice. A performer, his mother was held back from singing and dancing on stage in the 1920s and ’30s. She wanted Herrera to have the freedoms she was denied. “She told me, ‘I’m not going to hold you back like I was held back,’” said Herrera. “She didn’t want done to me what had been done to her.”

Herrera, Harjo, and Cisneros also spoke the next day at a public lecture at the Iowa Memorial Union, where they read from their works and shared how tapping into hardship can fuel creativity. “Poems come from when our hearts are broken open,” said Cisneros.

MORE FROM LNACC'S RENOWNED ALUMS

Iowa Magazine spoke with the three writers to dig deeper into their inspirations and creative journeys.

Sandra, you’ve described writing The House on Mango Street as a “quiet” revolution. Can you say more about that?

Cisneros: I was raised to be a good Mexican daughter, so [at the workshop] I would do things that to me seemed very radical, but no one else knew it was radical. The workshop would have a poem about a swan, and I would write about the opposite of a swan, you know, a rat. I felt like I was this little mouse throwing a brick. Maybe nobody knew I was reacting and upset, but I knew what I was doing, and through that resistance I discovered my voice. It turned out to be a great thing, because one of the things they don’t teach you is: What do you know that no one else in this room knows? That’s what I discovered in Iowa without realizing it. Then I said, I’m going to write something that you cannot tell me that I am wrong. I’m an expert on sitting on back porches that are ugly. I’m going to write about an ugly back porch.

Joy, what was it like to be a young poet in the 1970s?

Harjo: It was so different then. You wrote letters, you talked to people on the phone, you met with people. It was exciting. I was involved in seeing actual changes come about—like Roe vs. Wade, or the American Indian Religious Freedom Act—being involved in this trajectory of justice and then knowing that your voice mattered, or we had a place we didn’t before.

There was a sense that poetry was a living field, you know, not just Euro-American male literature or people from the 1800s or 1900s. It wasn’t necessarily always like that. I think about all those stories of women publishing under men’s names, or men taking over their work, and not having a place to publish, especially if you’re a Native woman writer. We were not anywhere. We were not in our textbooks. We were not in literature.

But we have to use the material of our lessons, our challenges, our failures. We take all of that and make a pathway through it. And not just for ourselves. I think of it like hand holds in the sky, for instance, for those who come after.

Juan, what questions about identity were you asking yourself in your 20s?

Herrera: In the late ’60s when I was at UCLA, everybody was talking about Chicano and feminism and gay identity. In the Chicano group, we were saying that we had Aztec and Inca ancestors. I said, wait a minute, that’s true. But we haven’t met Aztecs. We haven’t had communion with the Nahuatl peoples of central Mexico. Something is missing here. So, I wrote up a proposal to the Chicano Studies Research Center, and I gathered a group of funky friends, and I said, we’re going to go to visit the Totonac people, and the Lacandón Maya, and people of central Mexico, and we’re going to bring back artifacts and film interviews and recordings. So that was a step to the question of identity.

Do you feel like poetry can change the world? What has been your experience of that?

Herrera: When we write, we take a dream as an object, and then we write about the dream and create another object. But if the poem is really a stream of kindness in whatever manner it does that, and compassion for all life, that’s when things change. But if we veer off into description, into something that looks fun, or complex, or abstract, and we think that’s groovy, well it is, but what’s the core of it? There’s a lot of suffering, wars, people get mistreated and separated and ridiculed—only compassion can heal that, not my fun words and my groovy caesuras.

Cisneros: Yes, if you do it with your heart, with no personal agenda, no ego involved. Sometimes we don’t see in our lifetime the harvest of the seeds we plant. Sometimes it takes generations. But I’m very lucky that I’ve witnessed how my art changes people. I get testimonials that say, “This was the first book I read in English, and it really helped me to get through a difficult time as an immigrant.” People cry and they tell me things and then I cry because the things they tell me are so glorious.

Harjo: As poet laureate, I’ve done a lot of travel, visiting communities and universities. That role showed me how important poetry is to the soul of the nation. When you’re dealing with trauma, literature and art help keep your heart open. Only then can you find your way.

PHOTO GALLERY

The Latino-Native American Alumni Alliance Reunion, which celebrated more than 50 years of the Latino Native American Cultural Center, brought University of Iowa students and alumni together for a fall weekend in Iowa City. Here are some photo highlights of the reunion.