Kinnick's Final Days

I flew up in the clouds today—tall, voluminous cumulus clouds. They were like snow-covered mountains, range after range of them. I felt like an alpine adventurer, climbing up their canyons, winding my way between their peaks—a billowy fastness, a celestial citadel. Diary of Nile Kinnick, May 9, 1943

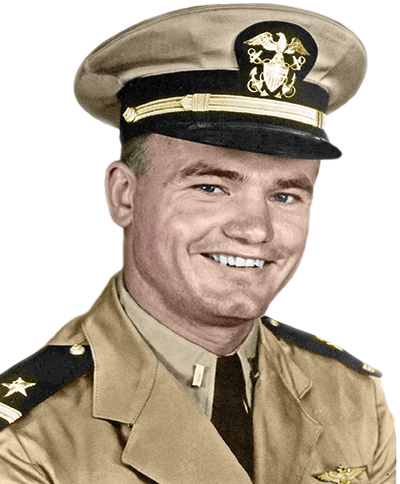

Photo:UI Special Collections, Nile Kinnick Digital Collections

U.S. Navy Ensign Nile C. Kinnick Jr.

Photo:UI Special Collections, Nile Kinnick Digital Collections

U.S. Navy Ensign Nile C. Kinnick Jr.

The young fighter pilot opened his gold-stamped notebook after a day in the sky and landed a few of his thoughts on paper. Nile Kinnick, the college football star and law student turned Navy man, was preparing to ship out for South America aboard the U.S.S. Lexington as war raged around the world. It was Mother’s Day 1943, an occasion he noted at the top of his journal entry. As he’d told his mother, Frances, in a recent letter back home to the Midwest, “My thoughts shall be loaded with flowers and everything lovely and good.”

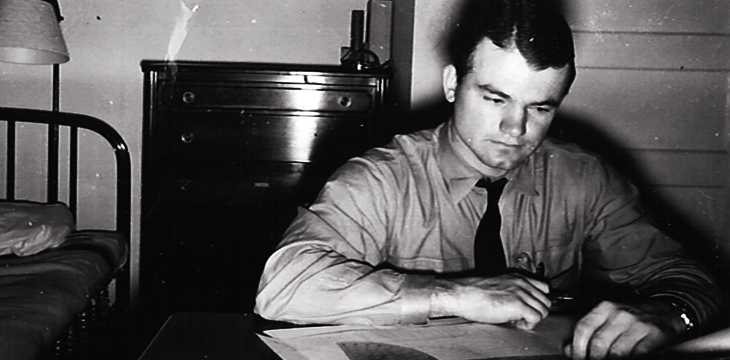

But politics, economics, and social issues also weighed on the mind of the brilliant 24-year-old. He had exhausted two spiral notebooks since being called up by the Navy Air Corps Reserve shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor and had begun filling a third. On this night, after journaling about the New Deal and the living conditions of striking coal miners, Kinnick couldn’t shake a nagging vision from his sleep—one that, through the lens of history at least, harbored echoes of a premonition.

“Wild dreams,” he wrote. “Lying in field with planes making forced landings and one turns out to be a horse.”

Twenty-four days later, Kinnick and his fighter plane sank in the waters off the coast of South America—Iowa’s celebrated son lost forever to the sea, to war, to history.

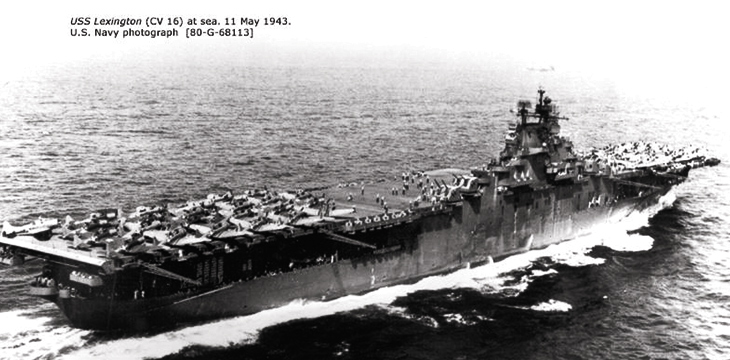

Exciting, adventurous is the life aboard a carrier. Diary of Nile Kinnick, May 11, 1943

Photo: U.S. Navy Archive Photo

The U.S.S. Lexington on May 11, 1943—the day the air craft carrier embarked from the East Coast for the Caribbean.

Photo: U.S. Navy Archive Photo

The U.S.S. Lexington on May 11, 1943—the day the air craft carrier embarked from the East Coast for the Caribbean.

The newly commissioned U.S.S. Lexington set sail for the Gulf of Paria, a Caribbean inlet tucked between the east coast of Venezuela and the island of Trinidad, on the second Tuesday of May. The 820-foot-long aircraft carrier was to test its operations on a shakedown cruise before joining the war effort in the Pacific. Ensign Nile Kinnick, the dimple-chinned Midwesterner, was among the crew of nearly 3,000. Far from a typical junior naval officer, Kinnick was a national celebrity for his football heroics four years earlier at the University of Iowa, where he won the Heisman Trophy and eclipsed Joe DiMaggio for the Associated Press’ Athlete of the Year award. The honors student had turned down a hefty contract to play professional football and instead opted to return to the UI for law school. The war, however, derailed those ambitions.

Although he famously said in his Heisman acceptance speech at New York’s Downtown Athletic Club that he thanked God he was “warring on the gridirons of the Midwest and not on the battlefields of Europe,” his growing sense of duty as the war escalated was impossible to ignore. Kinnick registered for the nation’s first peacetime draft in 1940 and was called to duty with the Navy Air Corps Reserve in December 1941. Once in uniform, he declined offers to remain stateside to play on wartime football teams for the Navy.

“Under way at last after eight days delay, around noon—beautiful day—sunny, good breeze, low scattered clouds. On the bosom of the deep—gentle pitch and roll of the ship,” wrote Kinnick on May 11 as the Lexington embarked from Virginia on its maiden international voyage. Kinnick had spent the preceding months at a naval air station at Quonset Point, Rhode Island, and wrote his parents that he was ready and eager for what lay ahead. With a year and a half of training under his belt, he was raring to test his piloting skills at the front.

Photo: UI Special Collections, Nile Kinnick Digital Collections

Kinnick in his flight suit.

Photo: UI Special Collections, Nile Kinnick Digital Collections

Kinnick in his flight suit.

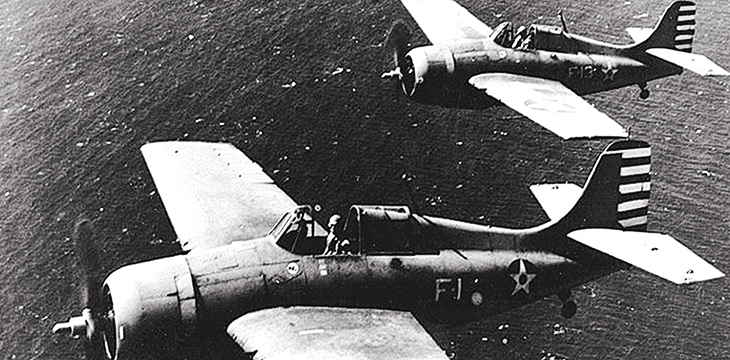

A member of Fighter Squadron 16, Kinnick flew a Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat, a single-seat, single-engine fighter plane with six fixed machine guns. He admitted he wasn’t his squad’s ace, but ever the competitor, doggedly worked to improve his marksmanship during his squad’s gunnery exercises, glide bombing runs, and group tactics training.

As the Lexington plowed southward through the Atlantic, Kinnick spent his free hours reading and filling his journal with quotations from books as varied as The Folklore of Capitalism, War and Peace, and the Bible. Laying on the deck at dusk and watching fish leap in the ship’s great wake, Kinnick turned over the words of Tolstoy. “What are the forces which move peoples and nations back and forth between war and peace?” he asked in one journal entry.

Kinnick’s writing in his final weeks reflected a man deeply interested in world affairs, devoted to his Christian Science upbringing, and committed to his family’s Midwestern work ethic and principles. Those close to him understood Kinnick was destined for things even greater than what he achieved on the football field. The grandson of George Clarke (1878LLB), who served as Iowa’s governor from 1913-17, Kinnick dipped his toes into politics before the war. Kinnick lent his celebrity to back FDR opponent Wendell Willkie in the 1940 presidential election and introduced the Republican presidential candidate at an Iowa rally. He particularly admired Winston Churchill and wrote glowingly of the British prime minister after reading his biography.

Two decades before the Civil Rights Era, Kinnick was also keenly interested in issues of human rights and equality, and he witnessed firsthand the plight of black Americans in the South while in flight school. “All people of whatever creed, nationality, or color must be accorded equal dignity and human worth,” Kinnick wrote that May. “Both Christianity and true democracy demand this fundamental acknowledgement.”

The only thing that pulled Kinnick away from his books was a good game of bridge, which he and his shipmates spent hours playing aboard the Lexington. He might have had those cutthroat card games in mind when he wrote in his diary: “If you really want to win, never give a sucker a break. Press every advantage to the limit.”

After a five-day voyage, the Lexington arrived May 16 at the Gulf of Paria, entering the semi-enclosed tropical sea via a passage called the Dragon’s Mouth. There the ship would spend the coming weeks waging simulated attacks while Kinnick and his fellow pilots sharpened their flying skills.

In between, Kinnick took advantage of the occasional chance to stretch his legs on land. On one such day without flight operations, he and the other pilots swam at an officers’ club on the beach in Trinidad. Then on May 29, just four days before his last flight, Kinnick joined crew members for a “big ballgame” on the beach—likely baseball, though he didn’t specify in his journal. For a man once called the Cornbelt Comet, who spent his childhood with a baseball, basketball, or football in his hands, and whose parents filled scrapbooks with newspaper clippings of his achievements, it would be his last game. “We lost, but it was a lot of fun,” he wrote that night.

That little town means so much to me—the scene of growth and development during vital years—joy and melancholy, struggle and triumph. It is almost like home. Nile Kinnick, writing about Iowa City in his final letter, May 31, 1943

Even amid the daily rigors of training at sea and the perils of Pacific battles looming, Kinnick’s letters kept him connected with home—Adel, where he grew up; Omaha, where his family moved before his senior year of high school; and Iowa City, where he made his indelible mark as a scholar and athlete.

Kinnick last roamed the Midwest and the UI campus the previous fall, in September 1942, on leave for three weeks after earning his Navy wings in Pensacola, Florida. Kinnick paid visits to friends and family in St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, and Adel, before hopping aboard the Rock Island Rocket from Des Moines to Iowa City.

On a chilly autumn weekend, Kinnick arrived at the old train depot near campus. Assistant athletic director Glenn Devine (22BA) fetched Kinnick from the station and drove him to the Field House, where his former team was dressing for practice the day before the season opener. Outside the locker room, coaches and sportswriters welcomed home the former star athlete and student body president. Head coach Eddie Anderson, who had led the famed Ironmen team to a 6-1-1 season in 1939, suggested Kinnick join the workout, so he tossed on a pair of sweatpants and a quarter-sleeve shirt and kicked a few footballs around the field. “Didn’t do badly either,” Kinnick later wrote.

After practice, Kinnick met up with friends for dinner at the student union. “It was just like old times—eager appetite, good food, lusty, happy companionship, the prospect of a game the next day; I enjoyed every minute of it,” he wrote. Later, he and a friend took dates to the Mayflower Inn along North Dubuque Street and a night spot in the nearby town of Tiffin, where Kinnick ran into a number of familiar faces.

On Saturday, Kinnick ate lunch at his former fraternity house, Phi Kappa Psi, where he was happy to see his former housemother and cook. On his way to the football game, two staff sergeants from his ROTC days greeted Kinnick with hearty handshakes instead of salutes. Then once at Iowa Stadium, Kinnick stopped in the locker room to meet with the team before heading to the press box, where he mingled with university president Virgil Hancher (18BA, 24JD, 64LLD) and other local leaders. Kinnick sat down for a radio interview with WSUI at halftime, and word quickly spread in the stands that Kinnick was at the game. Soon, the crowd took up the chant, “We want Kinnick! We want Kinnick!” In his khaki Navy uniform, necktie, and well-polished shoes, the All-American stepped outside the press box and waved his officer’s cap to the roaring crowd. The spirited day ended with a Hawkeye victory, 26-7, over St. Louis’ Washington University.

“Wasn’t it wonderful!” Kinnick later wrote about the hero’s welcome in the stadium that, exactly 30 years later, would be renamed in his honor. “Such a fine, spontaneous gesture! Certainly the people of Iowa have been good to me.”

Kinnick’s nostalgic visit lasted another two days. A theater and film lover, he saw two movies while in Iowa City: Pride of the Yankees and Talk of the Town. He stopped by the law school to catch up with his old professors, strolled downtown to chat with business owners, and attended a church service. On Monday, he dropped by a practice for the Iowa Navy Pre-Flight School football team, which shared facilities with the university during the war. Several former Hawkeyes were on the Iowa Pre-Flight team’s roster, and Kinnick reunited with Ironmen teammates Al Couppee (47BSC) and George Frye (47BSPE). When Kinnick said farewell aboard a Monday afternoon train for Chicago, he left Iowa City for the last time “secretly happy over the manner in which she had welcomed me back.”

If a man would grow in character his battle with self must be unceasing.Diary of Nile Kinnick, May 29, 1943

Photo: WikiCommons

Kinnick piloted a Grumman F4F Wildcat—like these fighter planes pictured over the sea during World War II.

Photo: WikiCommons

Kinnick piloted a Grumman F4F Wildcat—like these fighter planes pictured over the sea during World War II.

The Lexington crew had been training for more than two weeks in the Gulf of Paria when Kinnick climbed into the cockpit that fateful Wednesday morning—June 2, 1943. At 8:33 a.m., in quiet waters and good weather conditions, the Lexington launched Fighting Squadron 16 for practice operations. His Wildcat’s propeller roaring, Kinnick rocketed down the runway and into the skies over the Caribbean.

At 9:23 a.m., ship logs show that the attack group began a simulated, coordinated offensive. The first sign of trouble came at 9:51 a.m. when the Lexington’s radio crackled with concerning news: F4F-4 No. 7 had developed a serious oil leak. Crewman scrambled on the carrier’s deck in preparation for a deferred landing, while in the sputtering plane, Ensign Nile C. Kinnick Jr. fought his failing engine. Soon Kinnick lost all oil pressure and his engine seized, according to a later letter from his commander. Within sight of the flight deck yet still four miles out from the Lexington, it became clear Kinnick would be unable to make it back.

Pilot and bunkmate Bill Reiter was flying alongside Kinnick when he first spotted the oil pouring from his friend’s plane, according to a letter Reiter later sent Kinnick’s parents. Reiter radioed Kinnick to alert him of the problem, but little could be done. Reiter watched as Kinnick, calm and efficient, performed what he described as “a perfect wheels-up landing in the water.” From overhead, Reiter believed he saw Kinnick in the water and clear of the plane, though Kinnick didn’t signal. Reiter raced to the approaching rescue boat and guided it back to the crash site, but all that remained when crews arrived were paint chips and a gasoline slick, according to various letters.

In a letter to the Kinnick family, Lt. Cmdr. Paul Buie said water landings were typically a relatively safe maneuver. Buie speculated that Kinnick’s safety belt may have broken upon impact with the water and the pilot struck his head, hampering his ability to stay afloat or inflate his life jacket. Another member of Kinnick’s four-man team that day, Ardis Durham Jr., later wrote to Kinnick’s father that he saw Kinnick perform “as sweet a water landing as I’ve ever seen,” then watched as the plane floated for a few seconds before sinking. A piece of yellow debris had floated to the surface, giving Durham a false sense of relief. But the plane—along with Kinnick—vanished into the ocean. An hours-long search by hundreds was futile, and Kinnick’s body was never recovered.

Photo: UI Special Collections, Nile Kinnick Digital Collections

Kinnick read and wrote extensively during the war, leaving three war diaries and numerous letters to friends and family that are archived today in UI Special Collections.

Photo: UI Special Collections, Nile Kinnick Digital Collections

Kinnick read and wrote extensively during the war, leaving three war diaries and numerous letters to friends and family that are archived today in UI Special Collections.

Kinnick died just a month shy of his 25th birthday, his final resting place almost 3,000 miles from Iowa City. Two days before the crash, however, he wrote one last letter to reflect on the college town where crowds once chanted his name, where he pored over law books and yearned to make a difference in the world, and where his legend was born.

“That little town means so much to me—the scene of growth and development during vital years—joy and melancholy, struggle and triumph,” Kinnick wrote in the letter to Celia Peairs, a friend he’d dated before the war who’d recently visited Iowa City. “I love the people, the campus, the trees, everything about it. And it is beautiful in the spring.

“Ah, for those days of laughter and picnics when the grass was newly green and about a grab and a half high. ... I hope you strolled off across the golf course just at twilight and felt the peace and quiet of an Iowa evening, just like I used to do.”

Kinnick never forgot Iowa City. And 75 years after his death, Iowa City hasn’t forgotten Kinnick.