Newsreel of the Seahawks in action during their victory over Michigan in 1942

On the last day of August 1942, a group of 70 naval officers and cadets reported to duty at a sunbaked field next to Iowa Stadium—today known as Kinnick Stadium. They gathered around Bernie Bierman, a white-haired lieutenant colonel who had put out the call for volunteers at the newly commissioned U.S. Navy pre-flight school on the University of Iowa campus. Among the servicemen was a tall, broad-shouldered platoon leader named Forest Evashevski, who taught hand-to-hand combat at Iowa Pre-Flight.

Despite the searing afternoon heat, the drills were a welcome diversion from the turmoil elsewhere in the world. The following day would mark three years since Hitler's army invaded Poland and set in motion the deadliest war the world had ever seen. Japan's sneak attack on Pearl Harbor nine months earlier drew the U.S. into the war, prompting college campuses across the nation—including in Iowa City—to lease their facilities to the military for training grounds. But for an hour and a half, Evashevski and the other men could forget about the perils that lay ahead. Fall was coming, and even with the world at war, there was football to be played.

Soon, leather balls whizzed overhead, and Bierman's whistle competed with the thumping of punts and shoulders cracking against tackling dummies. It was the inaugural practice for the Iowa Pre-Flight Seahawks, who over the course of three short seasons would become one of the nation's best war-era teams. For the 23-year-old Evashevski, a former star quarterback at Michigan, it was his first day of football in Iowa City—a preamble to his return a decade later as head coach for the UI, where his Rose Bowl teams became the stuff of Hawkeye legend.

This fall marks the 75th anniversary of that Iowa Pre-Flight team, which from 1942 through 1944 boasted a veritable all-star cast of coaching greats, college standouts, and even NFL players who converged in Iowa City for naval training. In an effort to preserve the college game during a time when dozens of universities mothballed their football programs, military schools like Iowa Pre-Flight were allowed to compete collegiately and the prohibition against professional players was lifted. Across the nation, a number of star-filled service teams emerged, but none proved better than the mighty Seahawks, whose nickname reflected this unique wartime marriage of the Navy and Hawkeye State.

Last year, the Associated Press released a list of its top 100 college football teams of all-time based on the rankings it's compiled since 1936. Remarkably, Iowa Pre-Flight made the list as the No. 98th best program, despite playing just 31 games over three seasons. (Iowa ranked as the No. 25 program of all time.) Even more, the 1943 Seahawks, whose only loss came by a single point against eventual national champion Notre Dame in a game for the ages, are still considered by many experts to be among college football's greatest teams. The three Seahawks squads went a combined 26-5, outscored their opponents 801-315, and finished with two AP top 10 finishes. The Seahawks twice played the Hawkeyes at Iowa Stadium, cruising to victory in 1943 and 1944 against UI teams depleted by the war.

Yet the Seahawks' legacy today is largely relegated to the footnotes of football history. In Iowa City, the vestiges of the team are contained in just a couple of boxes at UI Special Collections—stacks of fragile photos, game programs, and the pre-flight school's old newsletter, the Spindrift. Outside South Quad, which was built by the Navy in 1942 and currently houses the UI's ROTC program, a small plaque commemorates the commissioning of the pre-flight school. But there are no Seahawks artifacts on display at the UI Athletics Hall of Fame, and UI Athletics leaders aren't aware of any remaining traces of the team on campus. Indeed, in a town with deep college football and military service traditions, memory of the Seahawks has largely faded with time.

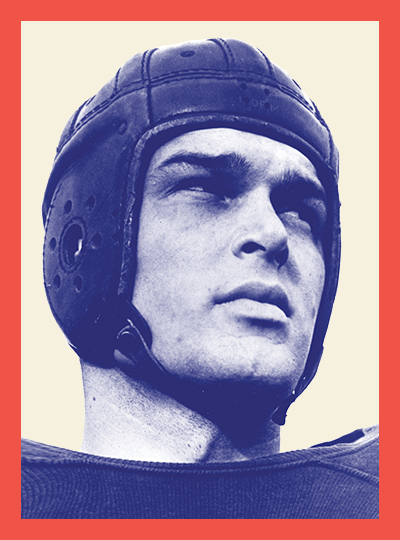

PHOTO: UM football, Bentley historical library, University of MichiganForest Evashevski

PHOTO: UM football, Bentley historical library, University of MichiganForest Evashevski

On April 15, 1942, UI President Virgil Hancher, 18BA, 24JD, 64LLD, ceremonially handed over use of university facilities to Navy Rear Admiral John Downes, establishing one of four pre-flight schools around the nation. University and Navy dignitaries joined hands to form a "V" for victory as they raised the flag on the east lawn of the Field House. Quadrangle and Hillcrest residence halls became naval barracks, and aviation cadets soon filled much of the Field House and several acres of west campus playing fields. Over the next three years, more than 21,000 men went through pre-flight training in Iowa City—once referred to as the "Annapolis of the Midwest"—before heading to primary aviation training and naval bases, ships, and cockpits overseas.

Sports played a central role in the cadets' 11-week regimen, which had three components: military tactics, academics, and athletics. Beyond football, Iowa Pre-Flight fielded a number of other varsity squads that competed regionally, including Seahawk baseball and basketball teams. Additionally, all men were required to participate in daily intercompany sports like boxing, wrestling, and swimming. Their sun-up to sun-down training was nothing short of grueling. As Downes put it, cadets were expected to "chop wood, dig ditches, go on 40-mile hikes, wrestle, box, and in all sorts of sports build up a strong, tough body."

The most notable Iowa Pre-Flight ensign was future astronaut and U.S. Senator John Glenn, among the first group of cadets to arrive at the new school in 1942. Glenn, who died in 2016 at age 95, didn't play varsity football, but his platoon was assigned to be "scrimmage fodder" for the Seahawks, as he described it years later.

The stars of the day, though, were the football players. Evashevski, for one, had made headlines across the nation for his exploits as a bruising blocking back from 1938 through 1940 at Michigan, where he cleared paths for Heisman Trophy winner Tom Harmon. As it happened, during Evashevski's autumn at pre-flight school, downtown's old Iowa Theatre played Harmon of Michigan, Hollywood's silver-screen depiction of that Wolverine squad in which Evashevski played himself. Several former UI players also lined the 1942 Seahawks roster, including halfback Bernard "Bus" Mertes, 47BSPE, 50MA; center George "Red" Frye, 47BSPE; and quarterback Al Couppee, 47BSC. Frye and Couppee were members of Iowa's famed 1939 Ironmen squad. They were joined on the Seahawks by former college standouts from schools such as Notre Dame, Minnesota, and Ohio State, along with pro players from the likes of the Chicago Bears and Green Bay Packers.

Bernie Bierman, the Seahawks' decorated coach, had a quiet but authoritative presence on the sidelines. The World War I veteran and Marine was the nation's top football mind at the University of Minnesota before the war. Under Bierman's charge, the Gophers recorded five undefeated seasons and were the two-time defending national champions before he was called to serve as director of physical training at Iowa Pre-Flight.

Despite the talent on hand in Iowa City, Bierman was skeptical about the Seahawks' ability to compete given the demands of their training. "Our cadet personnel is in constant flux, and we will have no single cadet from the first practice until the final game," Bierman said before the season. "No man on the squad has varsity football as his primary interest or responsibility. Cadets and officers alike must first go through their rigorous daily routine before going out for the football drills."

Military historian Wilbur Jones, author of Football! Navy! War!, says Navy leaders recognized football's benefit in developing toughness, leadership, teamwork, and hand-eye coordination—all skills needed in the air over the Pacific. "Many of these boys were trained as fighter pilots and ended up flying off carriers, and these teams attracted a lot of guys who were gung-ho about joining the Navy and Marine Corps," Jones says. "The physical training these players received helped tremendously in winning the war."

The Spindrift was the official newsletter for Iowa Pre-Flight School at the UI from 1942 through 1944. The mimeographed weekly paper was filled with school news, cartoons, gossip columns, and plenty of coverage of the Seahawks athletic teams. Staff artist Ted Drake illustrated issues from 1942-43, including portraits of athletes and officers. Every Spindrift issue is now archived in UI Special Collections.

Three weeks after their first practice, 36 Seahawks boarded a train bound for Lawrence, Kansas, for their 1942 opener. Because the UI team had first rights to its facilities, the Seahawks became barnstormers, playing the vast majority of their games on the road against the Midwest's major universities and other service teams. No game was scheduled against Iowa that season in part because of tensions over the shared athletics facilities.

Bierman's doubts about the Seahawks' readiness proved unfounded after the opening kickoff against the University of Kansas. Donning their white jerseys and leather helmets, the Seahawks stormed to a 61-0 victory, with seven different players finding the end zone. Just 3,000 fans witnessed the rout, and small Saturday crowds became the norm as households rationed gasoline, the government forbid fan train and bus trips, and interest in sports waned under the sobering hardships of war.

The Seahawks reeled off four straight victories to start the year, including a 7-6 upset over Minnesota, Bierman's former team that came in riding an 18-game win streak. The following week, Evashevski returned to his old stomping grounds and guided the Seahawks to a 26-14 victory over Michigan. Iowa Pre-Flight split its final six games—including a midseason setback at Notre Dame and a pair of losses at Ohio State and Missouri—to finish with a 7-3 record. Evashevski led the Seahawks in scoring on the year with five touchdown receptions, while Dick Fisher, a talented halfback from Ohio State, piled up 728 yards rushing and 533 yards passing.

"There was no give on the side of the pre-flight football players," Evashevski told the Voice of the Hawkeyes magazine in 1988. "I can remember leading a platoon on a 10-mile hike, then coming out and scrimmaging for an hour and a half."

When Evashevski returned to Iowa to coach in 1952, his Hawkeye teams would exhibit that same Seahawk toughness, including his storied 1956 and 1958 squads that won Iowa's first Rose Bowls. Evashevski became the UI's all-time winningest coach before leaving the sidelines in 1960 for the UI athletics director post, which he held for another decade. He died in 2009 in Michigan at age 91.

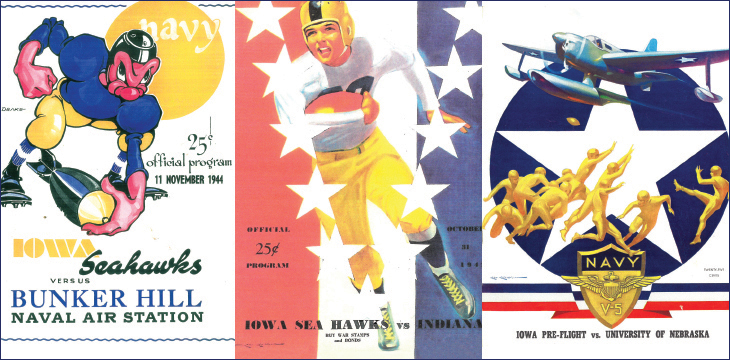

Programs: courtesy mark wilson

Programs: courtesy mark wilsonBy the time the 1943 season rolled around, Evashevski, Bierman, and company had departed and a new crop of enlisted men arrived in Iowa City. Don Faurot, an innovative coach from the University of Missouri, stepped in to guide Iowa Pre-Flight and brought his unique split-T offense—football's first option attack. With a backfield spearheaded by former Washington Redskins halfback Dick Todd, Marquette All-American quarterback Art Guepe, and returning team captain Mertes, Faurot's revolutionary offense was all but unstoppable. Iowa Pre-Flight toppled defending national champion Ohio State 28-13 early in the season, then overpowered the civilian Iowa team 25-0 in front of 8,000 fans at Iowa Stadium. The Hawkeyes, like many programs, were left with a bare cupboard because of the war, fielding inexperienced freshmen and 4-Fs—men excused from service because of medical conditions or other exemptions.

After handily winning their first eight games, the Seahawks climbed to second in the AP poll heading into a showdown at top-ranked Notre Dame—a rare meeting of No. 1 versus No. 2. In what newspapers described as one of the most dramatic games of the decade, the Fighting Irish scored a late touchdown, the Seahawks missed a potential game-winning field goal in the waning minutes, and Todd was carted off the field on a stretcher with a broken jaw. In the end, Notre Dame escaped 14-13.

The Seahawks bounced back in their season finale at Minnesota, cruising to a 32-0 win to finish No. 2 in the AP rankings behind the Fighting Irish. Todd was selected as the outstanding service player of the year by the Touchdown Club of Washington, D.C., while Iowa Pre-Flight became the nation's service team champion.

College football author Bill Connelly, who included the 1943 Seahawks in his new book, The 50 Best College Football Teams of All Time, said Faurot's use of the split-T at Iowa Pre-Flight was "one of college football's ultimate butterfly effects." Two assistant coaches on that 1943 team, Bud Wilkinson and Jim Tatum, spent the fall learning Faurot's system firsthand and took the split-T with them after the war. Wilkinson would go on to build a football dynasty at Oklahoma using the split-T, while Tatum found success with the option offense at Maryland. "Don Faurot could have easily run one of the basic formations of the day with that talent and they would have done just fine," Connelly says of the 1943 Seahawks. "But he was a tinkerer and a teacher, and his split-T adds another layer to their story."

PLAYER ILLUSTRATION: UI LIBRARies, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA, IOWA CITY, IOWA

Dick Todd, NFL Player and Seahawks halfback.

PLAYER ILLUSTRATION: UI LIBRARies, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA, IOWA CITY, IOWA

Dick Todd, NFL Player and Seahawks halfback.

In fall 1944, just a few months after Allied forces stormed the beaches of Normandy to begin the liberation of Western Europe, the Seahawks embarked on what proved to be their final season. As strong as the team was a year prior, the final Iowa Pre-Flight squad was just as formidable. Mertes, the powerful fullback, was the rare Seahawk veteran on a fresh-faced roster with an average age of 20. Jack Meagher, a Marine who had played for Knute Rockne at Notre Dame and coached at Auburn, helmed the team.

The campaign began inauspiciously for the Seahawks, who travelled to Ann Arbor, Michigan, for the 1944 opener. The Wolverines staved off Iowa Pre-Flight in a 12-7 slugfest that turned out to be the Seahawks' only setback of the season. Meagher's crew bounced back with a 19-13 win at Minnesota the following week, sparking a remarkable 10-game winning streak. Among them was a victory against a Purdue team that featured Chalmers "Bump" Elliott, a speedy halfback and Marine trainee who succeeded Evashevski as UI athletic director in 1970.

On Nov. 25, 1944, the Iowa Pre-Flight Seahawks took the field for a final time in a mutual home game against the UI. It was a bitterly cold and rainy afternoon at Iowa Stadium, where just 2,500 hearty fans witnessed the Seahawks' mud-splattered swan song. On hand was a large cheering section of uniformed cadets, as well as the Scottish Highlanders drummers and bagpipers, who performed at halftime. When the final gun sounded, the Seahawks left the field with one last triumph—a 30-6 win that boosted them to No. 6 in the final AP poll of the season.

Bob Smith, a halfback from Tulsa, led the 1944 Seahawks in scoring with 54 points, while Mertes capped his three seasons with Iowa Pre-Flight by earning AP Service Team All-America honors. Mertes would later play five seasons in the NFL, coach a number of college teams, and serve as an assistant on four Minnesota Vikings Super Bowl teams.

The Seahawk era ended with little fanfare. Within six months, the Allies celebrated Victory in Europe Day in the wake of Germany's surrender, and Japan capitulated in August 1945. The Navy decommissioned Iowa Pre-Flight, crowds welcomed heroes home, and former Seahawk coaches and players returned to their pre-war colleges and NFL teams.

At last, peace had won the day.

Although the Seahawks' gridiron feats were fleeting, their heroism and sacrifice ensured the Stars and Stripes still flies on fall Saturdays at Kinnick Stadium 75 years later. At war's end, the base's newsletter, the Spindrift, summed up Iowa Pre-Flight's legacy: "Its real story, its real value has been written in the Pacific skies, its worth has been shouted with bombs on Tokyo, and its valor has been proved by its boys who are up there somewhere beyond that wild blue yonder."

For Further Reading

Football! Navy! War!

by Wilbur Jones Jr., 2009, McFarland and Company

The 50 Best College Football Teams of All Time

by Bill Connelly, 2017, Mascot Books

Other Story Sources:

"Iowa Pre-Flight," by Gregg Duckworth, Voice of the Hawkeyes, Sept. 7, 1988; "Iowa Seahawks," 1942-44, by John B. Scott, College Football Historical Society Journal, November 1997, May 1998, November 1998; A Pictorial History of the University of Iowa by John C. Gerber, 2005, University of Iowa Press; Military and Wartime Service Records, University of Iowa Special Collections; Daily Iowan archive, University of Iowa Special Collections; Iowa City Press-Citizen archive, Iowa City Public Library.