IOWA Magazine | 09-11-2020

Self-Examination on the Road to Being Anti-Racist

By Sherry K. Watt

8 minute read

University of Iowa College of Education professor Sherry K. Watt shares steps for meaningful and transformational change.

"It has always been much easier (because it has always seemed much safer) to give a name to the evil without than to locate the terror within. And yet, the terror within is far truer and far more powerful than any of our labels: the labels change, the terror is constant. And this terror has something to do with that irreducible gap between the self one invents—the self one takes oneself as being, which is, however, and by definition, a provisional self—and the undiscoverable self which always has the power to blow the provisional self to bits." James Baldwin, "Nothing Personal" in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1964

The west side of my house was bare two summers ago. No landscaping. No trees. There was some erosion. To improve the look and address the soil slipping away, I planted six peonies along the house that summer. These plants were split and taken from a location where they had lived for many years. The next summer I packed mulch around the base of the bushes. I watered them occasionally. Only one of them started to bloom this year—just a few purple flowers. It takes a while for the plants to get over the shock of being moved and begin to bud.

Truthfully, I am doing nothing to nurture them. I do want the pretty flowers, but the labor involved exhausts me.

To help them grow, I have to water, mulch, and prod them along. I am not quite sure what drains me so when I am called to tend to plants. I do not want to join in that symbiotic relationship where they depend on me, and I am obligated to them. I then expect to see their blooms. What if I do all that work, and there are no blooms that year? What then is in it for me? How long will I have to wait on those blooms? There are so many factors to consider and aspects I have no control over. I cannot be certain that time and energy I put in will result in those beautiful blooms.

I do not trust those peonies. I'd rather they find their own way. I will then not care whether they bloom.

I am perplexed as I sit with how to relate with these peonies—perplexed as much as I am about how to traverse working with people to deconstruct racist policies and practices during a pandemic. I am an African American woman whose research addresses a timely question: How do we work through the barriers that derail productive communication about controversial social issues?

I understand that transformational change happens in relationship with others, over time, and often due to dissonance-provoking experiences. I have lived in Iowa for over 20 years. I teach students, faculty, staff, and community members how to develop the skills that build stamina for staying in difficult conversations that are also fruitful, authentic, and meaningful. And yet, I even question my own stamina to engage the overwhelming amount of dissonance during this stint in our country. Do I have the will to continue to engage with people and with a system that persistently treats me as other? Can I summon the strength?

As James Baldwin says, there are gaps between the actual self, the provisional self, and the undiscoverable self that might prevent individuals and organizations from embracing anti-racism societal change. What if people do not want to grow? What if they are not ready? What if it is not in their interest? What if the conditions are not right for them? I cannot trust that tending to their needs will result in personal or organizational transformation. I question whether my help will matter in their development of healthy blooms. If those peonies are not ready to bloom, they will not.

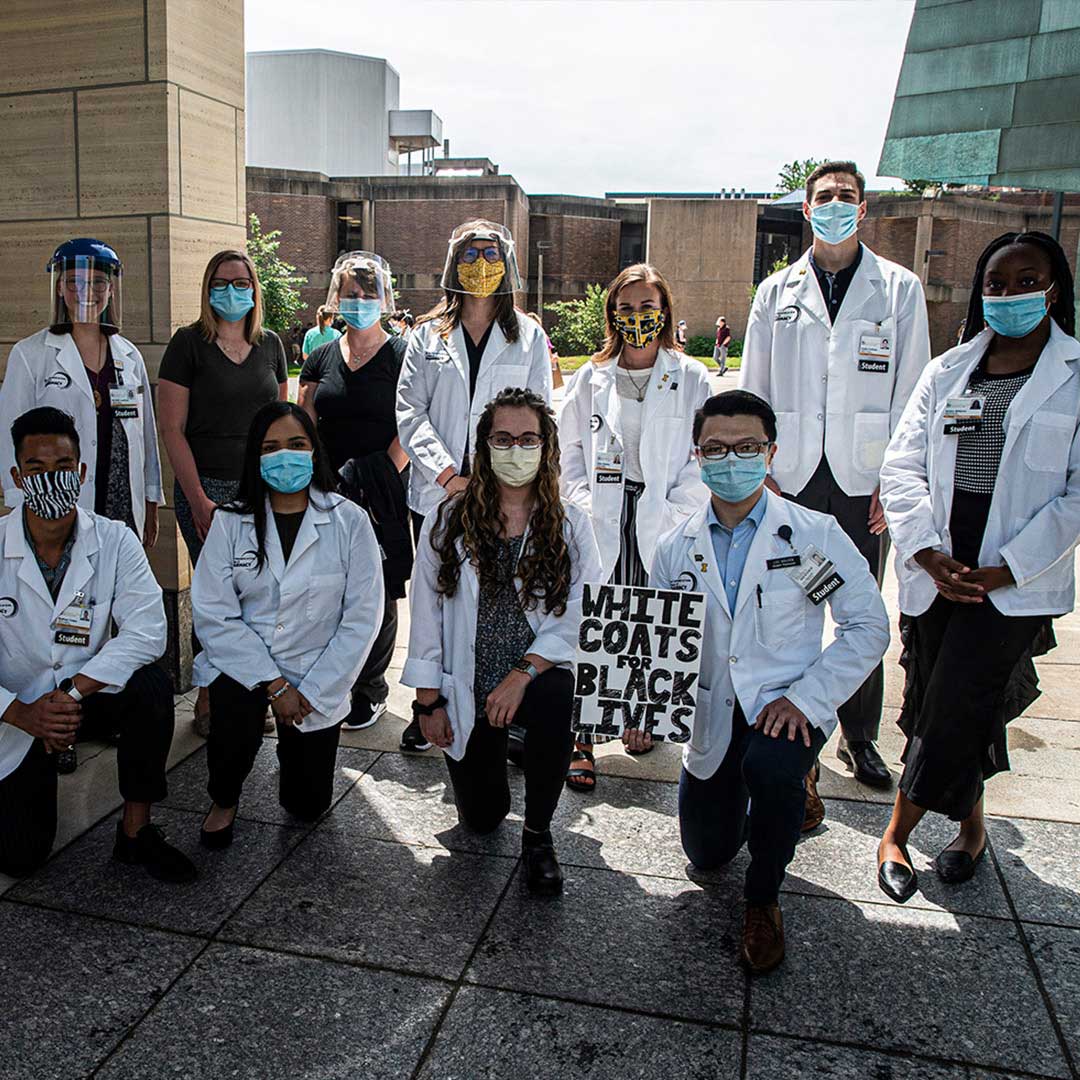

We live in hyper-polarizing political times. We are facing a pandemic that reveals fissures in our societal structure, all compounded by the intense social unrest brought about by the spring 2020 murders of Black Americans, including Ahmaud Arbery by vigilantes, and Breonna Taylor and George Floyd at the hands of police officers.

"You will not be able to create a diversity action plan or write a blog post that magically ends racism. We will not wake up one day and find that racism no longer exists. We must participate in the process of constantly unlearning centuries of racist ways."

I am afraid for my children. I am deeply saddened, angry, and exhausted.

In my despair, I turn toward what my research teaches me. The Theory of Being—developed by me and my colleagues with the MCI Research Consortium—focuses on the skills and environmental conditions that strengthen how to engage in difficult dialogues. We offer three process-oriented practices of "being with anti-racism work":

1. BEING WHILE DOING. Solutions are necessary, but the rush toward solutions often leaves groups (such as communities, college campuses, and agencies) with superficial fixes, additional problems, and further disagreement. We need a different approach than one that prioritizes outcomes without attention to process. Being with anti-racism work requires that we recognize racism entices each of us to behave inhumanely and in ways that are profoundly primitive, frantic, protective, and retaliatory. We, people of all races, must face the heavy burden and the reality that racism causes so much psychological and physical violence. We must be willing to work it out of ourselves and out of our culture.

In a recent blog post, Marcelo Bonta, founder of the Center for Diversity and the Environment, wrote, "Your job is to build your stamina and strength and strip off the unnecessary weight. Focus on the process. The process is where growth and progress occur and results in more impactful outcomes. The process is the work." We have to pay attention to how we are interacting while we are preparing our action. We must build relational trust and explore meaningful questions together: Who am I? Who are we? How have I been socialized to have racial biases? What am I willing to sacrifice for the common good? How might I disagree while holding intact the dignity of myself and others?

2. BEING, NOT PERFORMING. Anti-racism work calls for a focus on being with racism and not performing that you are not racist. There is no finish line. You will not be able to create a diversity action plan or write a blog post that magically ends racism. We will not wake up one day and find that racism no longer exists. We must participate in the process of constantly unlearning centuries of racist ways. This requires consciousness-raising, as well as an honest critique of our community values, attitudes, and beliefs. We also must place in historical context our societal laws, policies, and practices: Who am I? How did I come to believe what I do about society, myself, and others? How does what I believe align or misalign with how I present myself to the world?

Community members actively engaging in thoughtful dialogue with each other across differences is a first step in sustaining social change. Most importantly, each of us must reckon with the self and be honest about the ways we have aided and abetted structural racism.

3. BEING AWARE OF BEING DEFENSIVE. We live in a racialized society. Transformative anti-racism work will require that we talk about our disturbing current reality and face the uncertain future. Undoubtedly, these will be difficult conversations, and we must be aware that responding defensively is a normal human reaction. Humans become defensive when they have difficulty incorporating unfamiliar ideas or challenges to their value system. Our research on difficult dialogues reveals that reactions can be wide-ranging. We become overly emotional, devoid of emotion, overthink, or do not think at all. When I sit with what arises in me, I am more likely to listen long enough to hear the source of the disagreement and face it.

What do my defensive reactions teach me about me? What do I need to keep in mind when engaging across differences to have dialogue that is generative, humanizing, and reaches toward liberation for all people (the oppressed—and that includes white folk and their liberation from being oppressors—and for all who participate in an oppressive system)? How are my defenses preventing me from hearing the other side?

Peony bushes are perennials and can live as long as 100 years, but their flowers are in bloom only 7-10 days in the summer. I wonder what this teaches me about racial unrest over the history of this country. I need to see something that persists over time, that is transformative, and has longer lasting blooms. Moonbeam Coreopsis. They are hearty, stay in bloom from early summer all the way until late fall, and return every year.

Dr. Sherry K. Watt is a professor in the Higher Education and Student Affairs program at the UI College of Education. She is also the founder of The Being Institute (thebeinginstitute.org) and has more than 25 years of experience in designing and leading educational experiences to engage participants in dialogue that is meaningful, passionate, and self-awakening. Watt and her research team are working on two forthcoming books that focus on sharing research and practice on "ways of being" in difficult dialogues that examine social oppression and that inspire thoughtful, humanizing action.

Join our email list

Get the latest news and information for alumni, fans, and friends of the University of Iowa.

Join our email list

Get the latest news and information for alumni, fans, and friends of the University of Iowa.