At 125 Years, Duke Slater's Legend Still Burns Bright

PHOTO: UI ARCHIVES

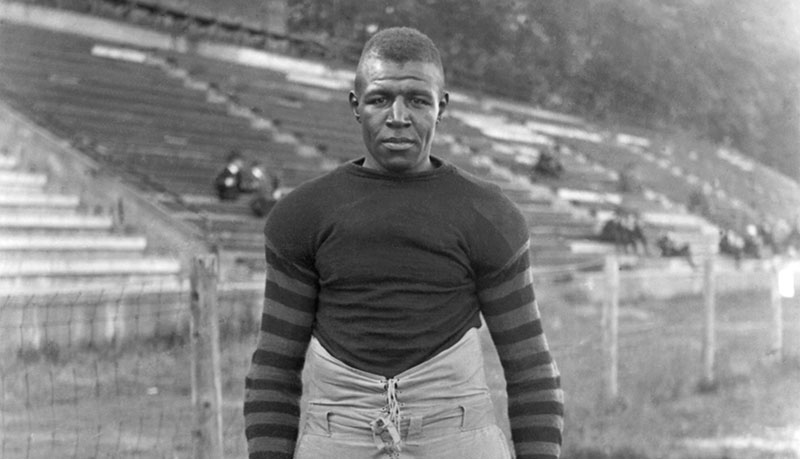

Pictured here in 1919, Duke Slater became the first Black member of the College Football Hall of Fame as part of its inaugural class in 1951. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2020.

PHOTO: UI ARCHIVES

Pictured here in 1919, Duke Slater became the first Black member of the College Football Hall of Fame as part of its inaugural class in 1951. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2020.

The extraordinary life of Frederick “Duke” Slater (28LLB) began 125 years ago this month. Iowa’s first Black All-American football player, Slater went on to become a distinguished judge and civil rights pioneer. Throughout his life, Slater remained a proud Hawkeye.

Today, more than a half-century after the scholar-athlete’s death, his legend only continues to grow. The University of Iowa named the field at Kinnick Stadium after Slater in 2021, and the lineman received a long-overdue induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame that same year. The eastern Iowa town of Clinton, where Slater was a high school football star, is currently working to memorialize its hometown hero with a new statue and scholarship.

So, as we remember Slater on his 125th birthday, let’s look back on how the Duke of Iowa City became an enduring Hawkeye icon.

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

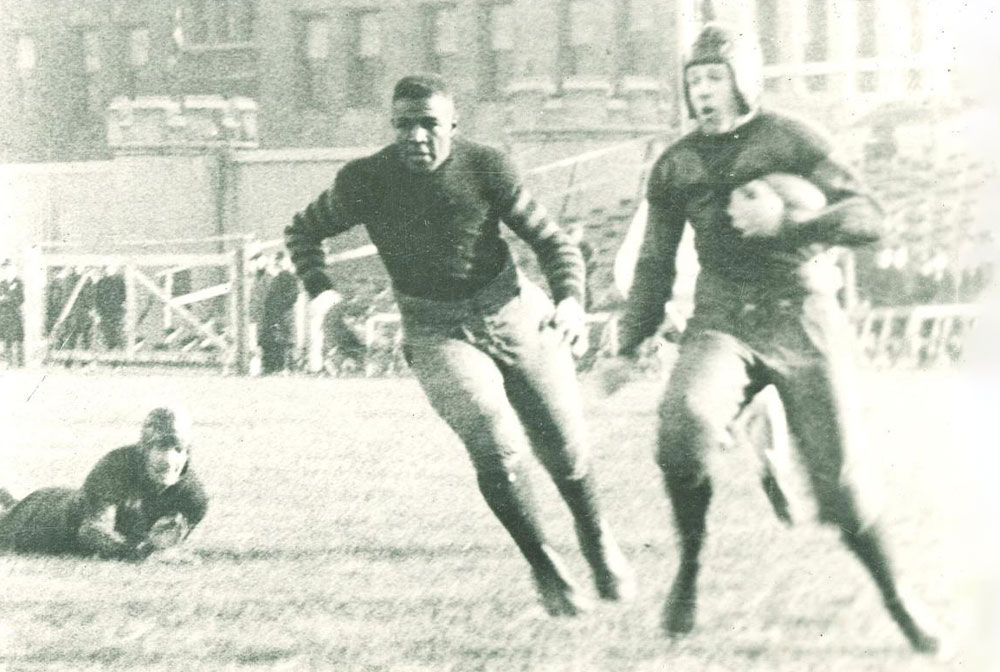

Duke Slater (center) helps clear a path for ball carrier Gordon Locke in a game in the early 1920s.

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Duke Slater (center) helps clear a path for ball carrier Gordon Locke in a game in the early 1920s.

The Helmetless Hawkeye

Slater was born in December 1898, in Normal, Illinois, the son of a preacher and the grandson of freed slaves. The exact date of Slater’s birth remains unclear; some sources state Dec. 9, while others say Dec. 19. University records simply state December 1898.

According to UI alumnus and Hawkeye historian Neal Rozendaal (02BS), who wrote the definitive biography Duke Slater: Pioneering Black NFL Player and Judge (McFarland & Company, 2012), Slater discovered his love for football playing neighborhood pickup games in Chicago’s working-class South Side. Slater was 13 when his family moved to Clinton, Iowa, where his father became the pastor at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

George Slater forbade his son from playing the violent sport, but Duke joined the Clinton High School team as a sophomore, nevertheless. One day, George discovered his wife sewing up Duke’s tattered jersey, and the ruse was up. According to a Chicago Tribune story archived in Slater’s file at UI Libraries Special Collections, Duke went on a hunger strike in protest for several days. George finally relented and made an agreement with Duke: The teen could continue to play football as long as he didn’t get hurt.

While Duke concealed his bruises and pains at home, his family had to compromise on one aspect of his safety. The Slaters didn’t have the extra $10 to buy Duke both shoes and a leather helmet for his high school football team, so his father told him to decide which he needed more. Duke chose the shoes, and he famously played his entire high school and much of his college career with his head unprotected.

“In thinking back, I’m sure Dad made a mistake. I wear size 14 shoes, and he would have saved money if he had bought the helmet,” Slater once joked.

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Duke Slater (helmetless at the bottom of the pile) paves the way for the Iowa running attack during the Hawkeyes' 10-7 victory over Notre Dame in 1921.

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Duke Slater (helmetless at the bottom of the pile) paves the way for the Iowa running attack during the Hawkeyes' 10-7 victory over Notre Dame in 1921.

Tower of Strength

Slater dished out more bruises than he received as a physically imposing lineman at Clinton, where he helped lead his school to two mythical state championships. His on-the-field exploits not only won him the admiration of townsfolk in an era when Black people faced daily discrimination, but he also caught the eye of several influential UI law school alumni and football team supporters, according to Rozendaal. Among them was Mike McKinley (1895LLB), a star for the Iowa football team in the 1890s who was then a Chicago Superior Court judge. The alumni helped coax the burgeoning football star to Iowa City, where he enrolled in 1916.

“No better tackle ever trod a western gridiron.” —NOTRE DAME COACH KNUTE ROCKNE

In those days, Black football players were few and far between, but Iowa already had a strong track record of equity on the playing field. Frank “Kinney” Holbrook and Archie Alexander (1912BE, 25CE) preceded Slater as Black standouts for the Hawkeyes. Playing under coach Howard Jones, the 6-foot-1, 215-pound Slater paved the way on the line for an unprecedented run of success for Iowa. He became Iowa’s first Black All-American, receiving the honor as a sophomore and again as a senior. Iowa won its first undisputed Big Ten title in 1921, posting a sterling 7-0 record.

Slater won over admirers nationally. The New York Times dubbed him “a tower of strength” and Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne declared, “No better tackle ever trod a western gridiron.” Added the Chicago Tribune: “He is so powerful that one man cannot handle him and opposing elevens have found it necessary to send two men against him every time a play was sent to his side of the line.”

PHOTO: Stephen Mally/hawkeyesports.com

A bronze relief installed in 2019 on the north side of Kinnick Stadium depicts a helmetless Duke Slater blocking the entire left side of the Notre Dame line in the 1921 Hawkeye victory that highlighted a perfect 7-0 season.

PHOTO: Stephen Mally/hawkeyesports.com

A bronze relief installed in 2019 on the north side of Kinnick Stadium depicts a helmetless Duke Slater blocking the entire left side of the Notre Dame line in the 1921 Hawkeye victory that highlighted a perfect 7-0 season.

Gridiron to Gavel

Slater enrolled in the UI College of Law following his senior season, but he needed a means to pay for his continued education. He had worked odd jobs throughout his undergraduate days, including helping build Iowa City’s Burlington Street bridge in 1920. But professional football offered better pay. Weighing several offers, Slater signed with the Rock Island (Illinois) Independents, one of the original teams in the two-year-old NFL, for a salary of $1,500 in 1922. The first Black lineman in league history, Slater soon put his law school plans on hold to fully pursue a career in pro football, where his feats became legendary. In 10 NFL seasons, Slater made seven all-pro teams as a member of the Independents and Chicago Cardinals. In 2021, he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame as part of its centennial class.

PHOTO COURTESY SLATER FAMILY

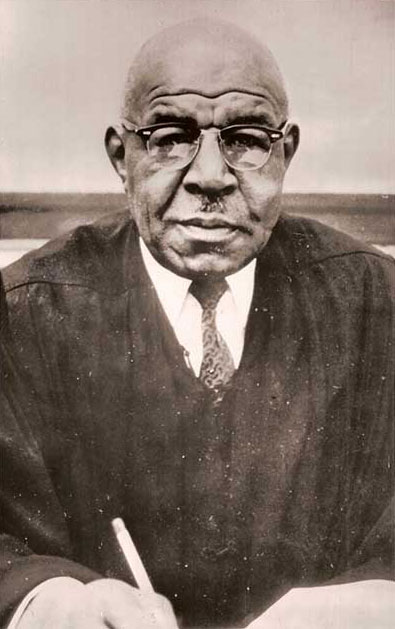

Duke Slater was Chicago’s second Black elected judge on the Cook County Municipal Court and, in 1960, became the first Black judge to be appointed to Chicago Superior Court.

PHOTO COURTESY SLATER FAMILY

Duke Slater was Chicago’s second Black elected judge on the Cook County Municipal Court and, in 1960, became the first Black judge to be appointed to Chicago Superior Court.

According to Rozendaal, Slater resumed his law studies in fall 1925 after a three-year absence, taking classes in the morning in Iowa City and practicing with Rock Island in the afternoon. He married fellow UI graduate Etta J. Searcy (21BA) of Muscatine, Iowa, the following year and earned his law degree in June 1928. The NFL’s only Black player for much of the late 1920s, Slater retired after a decade in the league and as one of the game’s most respected players. “I hung up my suit in 1931 when I realized that football is a young man’s game,” Slater once told the Mason City Globe-Gazette.

After his NFL days, Slater played for the Chicago Blackhawks, a team made up entirely of Black players, and founded and coached several Black Chicago semi-pro squads. The teams were necessary because, from the mid-1930s to mid-1940s, after Slater had left the league, NFL owners enacted a ban on Black players. Also a practicing lawyer, Slater was a prolific public speaker who challenged crowds to eliminate racial prejudice and once spoke at a fundraising dinner alongside Jackie Robinson, according to Rozendaal’s biography. He mentored and guided several young Black players to the University of Iowa, including All-American halfback Ozzie Simmons (40BSPE).

“In an era where African Americans in the sports arena were still subject to arbitrary bans on their participation in professional football and baseball, were forbidden from eating and living with white teammates, and were subject to numerous forms of discrimination, Duke Slater had found a way to rise above,” wrote Rozendaal.

Slater’s career in the courtroom was just as remarkable as on the gridiron. Slater settled in Chicago, where he became an assistant district attorney and, in 1948, was elected as a municipal court judge. Slater became the first Black judge to serve on the Superior Court of Chicago in 1960, and later joined the newly formed Circuit Court of Cook County. “Before him come the varied problems of the city, deeply underscored by race and socio-economics,” reported The Daily Iowan in 1957. “He brings sociology as well as legal insight to his judgement.”

PHOTO: Brian Ray/hawkeyesports.com

Duke Slater's niece, Sandy Wilkins, is recognized during a game at Kinnick Stadium in 2021, when Duke Slater Field was officially dedicated.

PHOTO: Brian Ray/hawkeyesports.com

Duke Slater's niece, Sandy Wilkins, is recognized during a game at Kinnick Stadium in 2021, when Duke Slater Field was officially dedicated.

Iowa City Icon

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Slater Hall was renamed after the Hawkeye legend in 1972.

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Slater Hall was renamed after the Hawkeye legend in 1972.

In 1972, six years after Slater’s death, members of his family gathered outside a residence hall formerly known as Rienow II, a block from the Burlington Street bridge Duke once helped build. His 10-year-old grandnephew, Frederick Slater Davis, cut the ribbon on the newly renamed Slater Hall, the first campus building named for a Black person.

The ceremony was especially meaningful because Slater had to live off campus in the days when Black students were barred from university dorms. As a student, Slater lived in the Kappa House with four Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity brothers. Still, Slater found opportunity at Iowa and had an affinity for the university, in spite of the discrimination he faced. Slater faithfully returned to Iowa City for football games and homecoming weekends and traveled to the Rose Bowls of the 1950s to cheer on his alma mater. “My uncle loved this institution,” his niece, Letha Coffey, told The Daily Iowan at the residence hall dedication.

In 2021, the UI officially renamed Kinnick’s playing field Duke Slater Field, nearly 50 years after former UI President Willard “Sandy” Boyd first floated the idea of a Kinnick-Slater Stadium. Although the committee in the 1970s ultimately declined to use a joint name for a facility, Slater’s name is now emblazoned in gold letters on the Kinnick Stadium turf. Slater is also enshrined outside the north gates of the stadium, where a 14.5-foot by 16-foot bronze relief depicts him—helmetless, of course—clearing a path for a ball carrier during the storied 1921 season. Inside the nearby Hansen Football Performance Center, a bronzed pair of Slater’s cleats is prominently displayed.

Iowa City isn’t the only place where Slater’s memory lives on. Ninety miles east, a committee in Clinton is currently raising money to install a life-size bronze statue of Slater and establish a new scholarship in his name. The monument, located across the street from the town’s high school and football field, is scheduled to be installed in 2024.

“Iowa is a great state,” Slater once said. “Young men have a fine opportunity to go on in school to prepare themselves for future life. If the youngsters are taken care of, we will have no fear of the future.”