Acclaimed Iowa Alumnus John Irving Reflects on His 'Last Long Train'

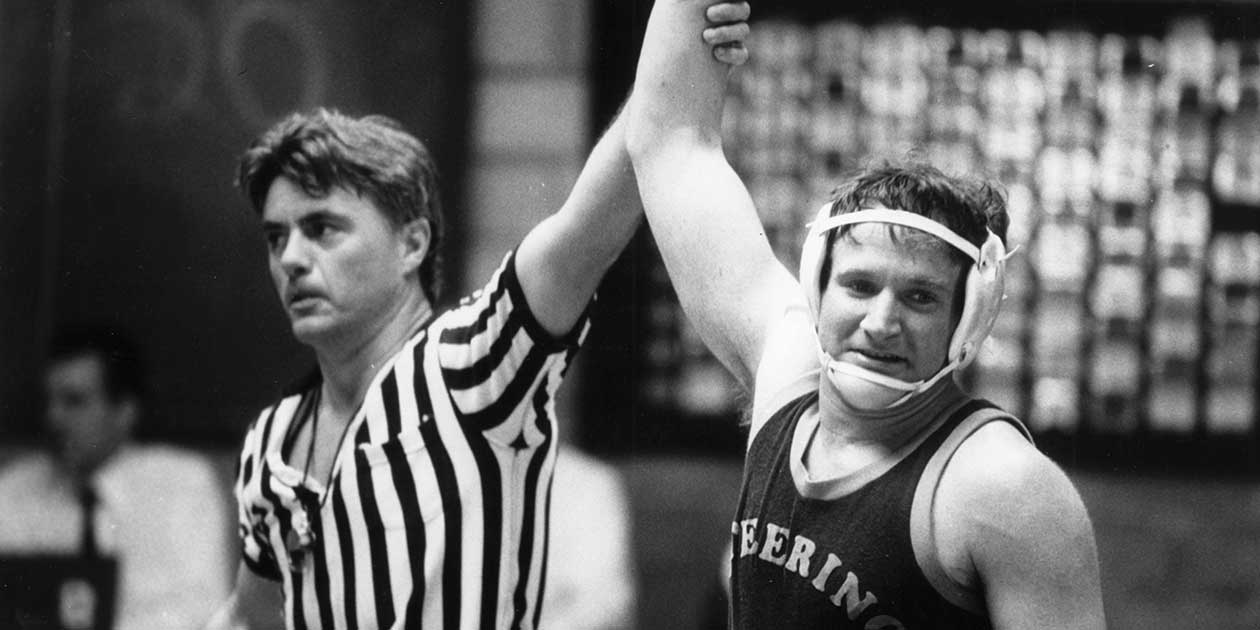

John Irving exploded onto the American literary scene with the publication of The World According to Garp, which won the National Book Award in 1980. The book was everywhere, printed with multiple different-colored covers so that bookstores could display entire racks of it next to the cash register. Four years later, the film adaptation starred a young actor named Robin Williams.

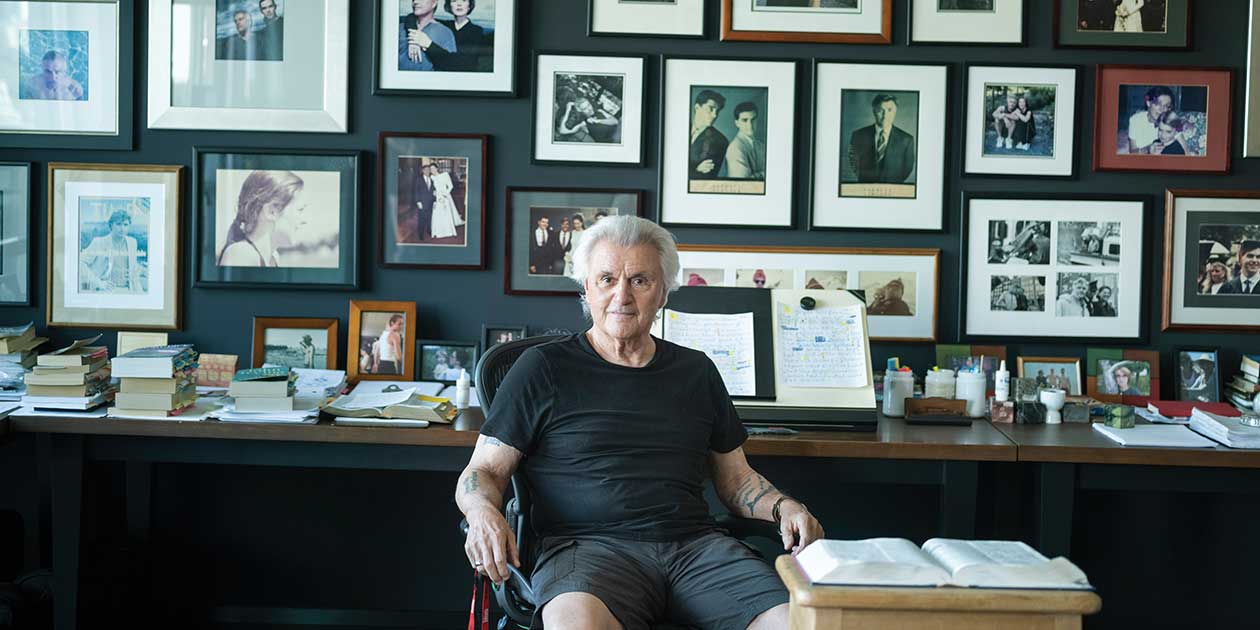

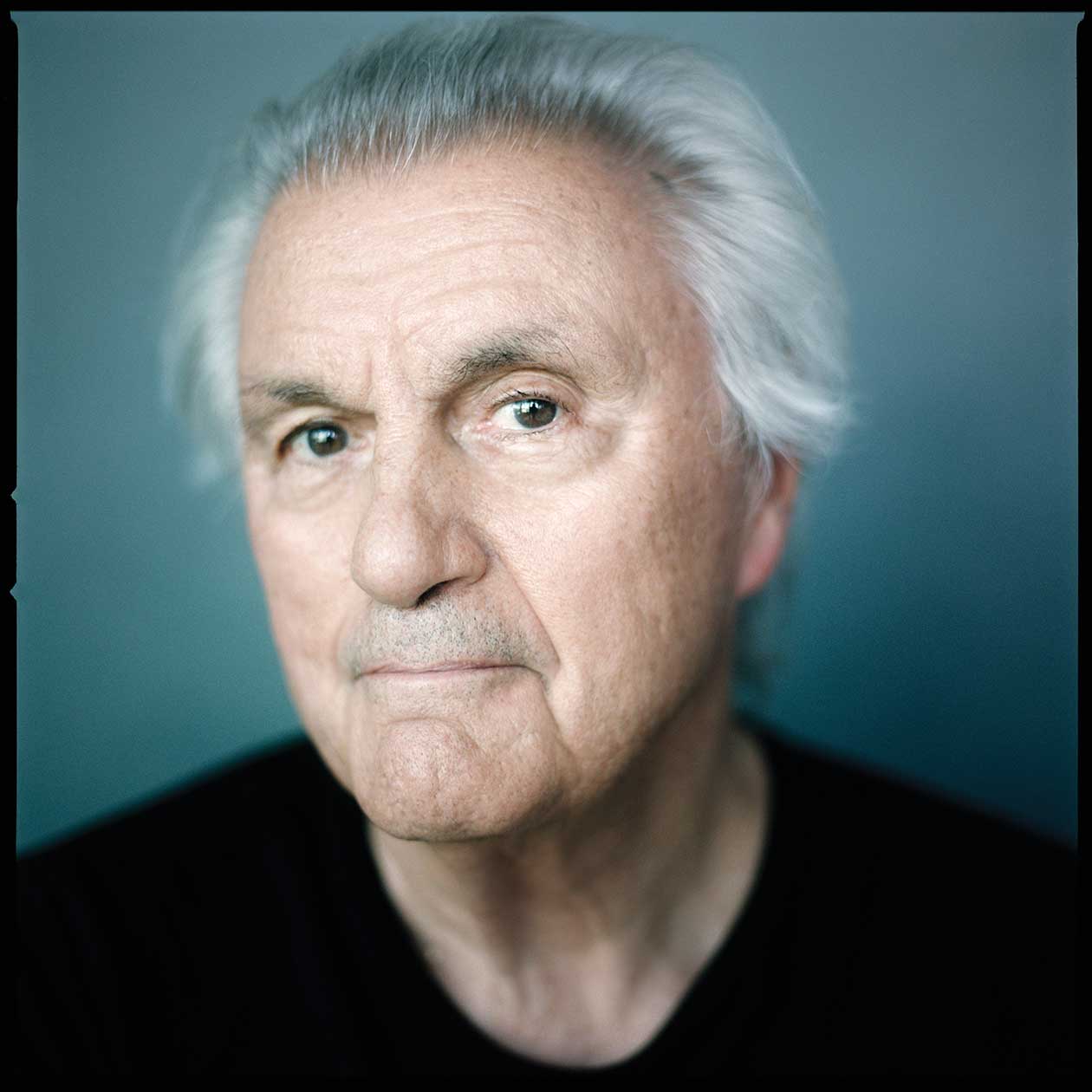

PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER WAHL/GETTY IMAGES

John Irving

PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER WAHL/GETTY IMAGES

John Irving

From his early days, Irving (67MFA) was dubbed a wunderkind, and indeed, he’d sold his first novel (his University of Iowa MFA thesis), Setting Free the Bears, in 1968 for $7,500 (about $65,000 today) while he was still a student in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. It was a feat almost unheard of in graduate writing programs in those days, when students would be thrilled to publish a short story in a college literary quarterly. Despite his early success, his novel before Garp, The 158-Pound Marriage, had sold fewer than 10,000 copies.

After leaving Iowa, Irving taught at Mount Holyoke College and at the short-lived Windham College in Putney, Vermont, where he feared failing an underperforming student meant the kid could lose his student deferment and end up fighting in Vietnam. He returned to teach at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop from 1972 through 1975, where he enjoyed mentoring students like T.C. Boyle (74MFA, 77PhD), but also wondered, like his character T.S Garp, if he was ever going to be a “real writer.”

Oh yes.

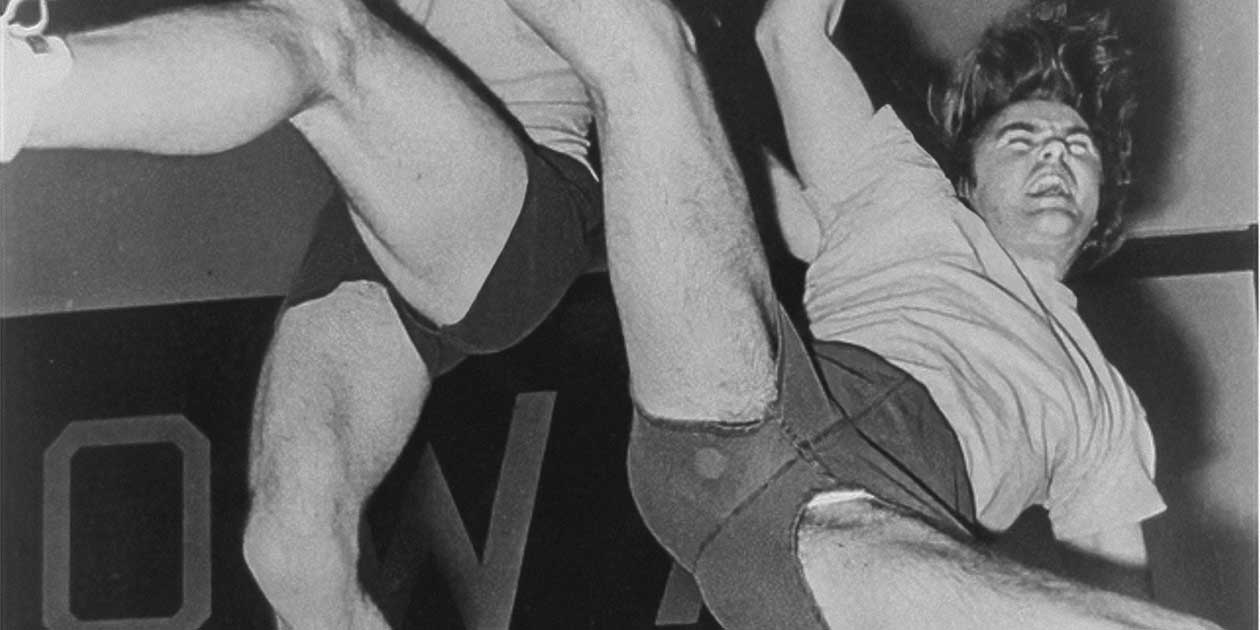

Garp changed everything, introducing us to Irving’s familiar themes and recurring obsessions: wrestling, New England prep schools, writing, sex, quirky characters, strong and powerful women, missing fathers, anfractuous relationships within self-configured families, and a resonant call for compassion in a world where we are all, as Garp says, “terminal cases.” The World According to Garp has the reader laughing one minute and sobbing the next, defining a landscape and a community as distinct to Irving as the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, is to William Faulkner.

It’s an artistic terrain Irving has returned to in many of his 15 novels, including his latest 900-page epic, The Last Chairlift, recently published by Simon & Schuster. It may be his most autobiographical novel yet, if a book where the protagonist’s grandfather getting hit by lightning while wearing only a diaper to his daughter’s wedding can be considered autobiographical. With a plot spanning the last 60 years, The Last Chairlift reads as a reimagining of Irving’s adult life, beginning with growing up in a skiing family. At 81, Irving says this is his last long novel.

We caught John Irving during his recent book tour for a conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Q: When you were in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, you supported yourself with three jobs. You were a teaching assistant, restacked books in the library, and sold pennants outside of Iowa Stadium, which is now Kinnick Stadium, during football games.

A: I must say, I enjoyed that job. It was great for people exposure. My two worlds in Iowa were the old wrestling room, before there was Carver, and the old workshop. It broadened that exposure considerably, working at Kinnick. It was a great atmosphere. It’s a great stadium.

Q: You grew up with dyslexia and weren’t diagnosed until you were an adult. But instead of turning away from writing, you turned toward it—how did that happen?

A: I was always behind in school. I just accepted that I was in a school, Phillips Exeter Academy, where I was over my head. I just got used to asking my friends, “How long did the English assignment take you?” And whatever they said, I would, in my mind, double it.

The difficulty notwithstanding, reading novels was a joy to me. How slow a reader I was didn’t matter. In fact, my habit of writing my novels in longhand is precisely because of how it slows me down. If I think of writing like drawing—it’s a conscious way of slower is better.

It was reading that made me want to be a novelist. It was Dickens’ Great Expectations, where I said, after I read it, “I have to be able to do this.” And that happened to me when I was 15.

Q: At the same time, you think of your stories in reverse. A lot of writers write to find out how the story ends. You know the ending before you start writing.

A: I was only 17 when I first read Moby Dick, but that was the novel that showed me how much you should know about an ending when you begin a novel—namely, everything. You know, when The Pequod sets sail, that they’re not going to make it. And you realize, if you’ve read that novel closely, Melville knew from the beginning, not just that The Pequod would sink, but exactly how Ishmael was going to survive.

Q: When you were in the workshop, there were only a couple dozen graduate writing programs in the country, and now there are close to 300, many established by Iowa graduates and based on the Iowa model. Thomas Williams (winner of the National Book Award in 1975 for The Hair of Harold Roux), your writing professor at the University of New Hampshire, was an Iowa alumnus who steered you to Iowa City.

A: Tom Williams was the guy who put Iowa in my head and told me that was where I should go. When I was still in prep school at Exeter, I found some really wonderful readers for my first fiction. They raised my expectations about what other readers could do to help me. I was already predisposed to listen to a good teacher or a good reader. Before I met Tom Williams, Frederick Buechner was the minister at Exeter when I went there, but he was also a novelist, and he set me up for Tom, because he was so good, so supportive.

Q: You arrived in Iowa City with a young family in tow. Did that give you a greater emotional reservoir to draw from when you sat down to write?

A: I was still an undergraduate when Colin was born. I was surprised because I thought I’d been in love before. I was unprepared for the unreserved, unrestrained love you feel for a child. You think, oh, my God, protecting this little person is—that is the rest of my life. Suddenly, there was no one I had ever felt as strongly about loving, or protecting, or as fearful for.

Q: As an MFA student, you connected with a relatively unknown young teaching writer named Kurt Vonnegut, and you saw something in him that other students didn’t see. They dismissed him as a mere science fiction writer.

A: I couldn’t have asked for a better mentor.

Vonnegut’s early books were in print. Player Piano was one. Many of my snotty fellow students at the workshop were already buying into a writer’s reputation before they’d read the writer. I thought the first job of a student at Iowa was to look at who’s on the faculty and read all their stuff. Those of us who chose to be with Vonnegut from the beginning were so lucky because we found ourselves in a very small class of students. My fellow writers turned up their noses and said, “I’m gonna work with Vance Bourjaily. I’m gonna work with Nelson Algren.” I read Vonnegut and thought, this guy is amazing. This is the guy who’s original, and who’s funny and serious at the same time. I identified with him. He was a very candid and lovely man. He wasn’t afraid to put his finger on what you didn’t do well, as well as the other things you did better.

What struck me about Vonnegut was something I recognized in Dickens and in Shakespeare—the simultaneity of the comic and the tragic—that you could be very funny when what you’re setting up is something very dark. And in fact, you might better prepare a reader for the very dark by being funny. Vonnegut was a master of that.

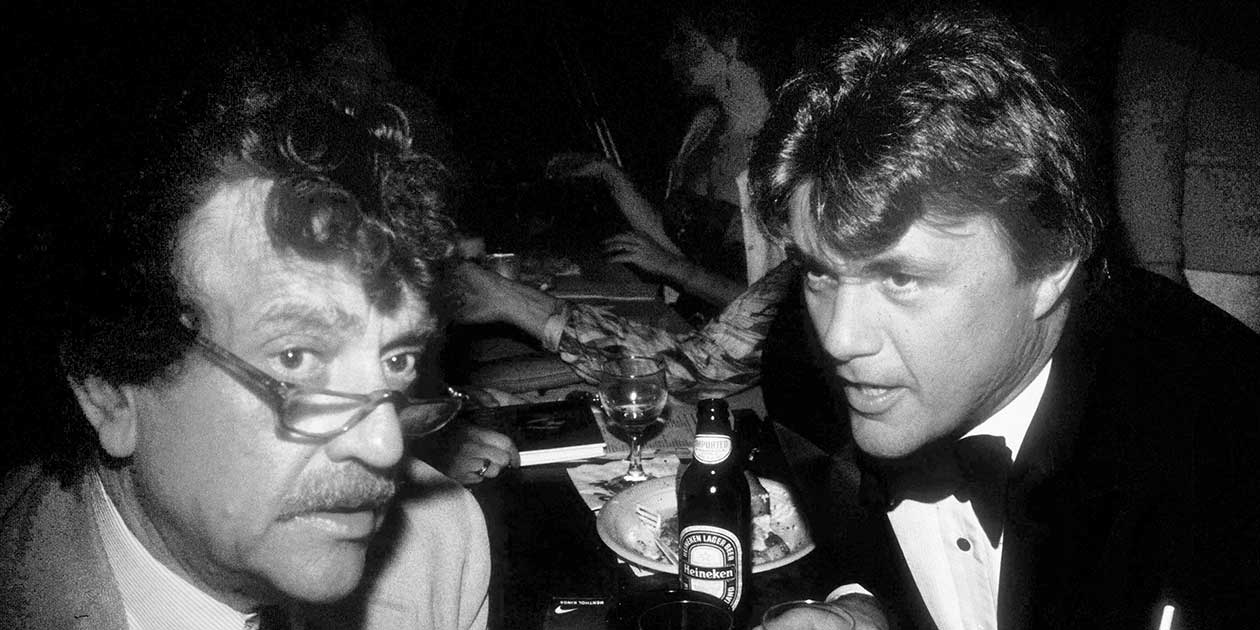

PHOTO: CELEBRITYARCHAEOLOGY.COM/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

PHOTO: CELEBRITYARCHAEOLOGY.COM/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

"I read Vonnegut and thought, this guy is amazing. This is the guy who’s original, and who’s funny and serious at the same time. I identified with him.” —John Irving, pictured alongside Kurt Vonnegut in 1990

Q: Did you know as you were writing The World According to Garp that it would be your breakthrough?

A: No, absolutely not. I even doubted my wonderful editor, Henry Robbins, when Henry said, “This book is gonna go big for you—you’d better get prepared.” I thought, Henry genuinely likes me, but he’s delusional. You have to realize that for the writing of my first four books, I not only was not self-supporting as a writer, but I had no reason to believe I ever would be. I thought I would always be teaching English and creative writing, and coaching wrestling, and finding the time to write when I could. I rarely had more than two hours a day to write, and not every day. I knew that, give me a whole day, give me seven days a week, and I could write more and write better. I didn’t dislike teaching, but I longed for a time when I could be that [Dan] Gable-like horse with blinders on, writing seven days a week, eight hours a day. It was only after The World According to Garp was published that I had the chance. By the time I got to The Cider House Rules, I used to have to set an alarm to remind me what time it was, or I would have written right through the dinner hour.

Q: What readers have found in Garp, and now in The Last Chairlift, is that they are about compassion, the moral calling to be sympathetic toward people who are not neurotypical or cisgender heteronormative. In Garp, we meet Roberta Muldoon, the transgender former NFL tight end. At the time you created her, in the late ’70s, the only benchmark might have been Corporal Klinger on M.A.S.H. It was a joke. You created this radically defiant woman who shocked people who were forced to empathize with her and see her as a human being. How did that reality affect your daughter, Eva, who is transgender?

A: It’s funny to think, with hindsight, that I made a hero of Roberta a long time before Eva was born. I always had a mantra that I heard my mother deliver when I was only beginning The World According to Garp. She was a nurse who worked in a county family counseling service, which meant she saw a lot of underage girls who were pregnant. She had to talk to them about what they faced, either having an abortion or a child, as an unmarried, underage girl, in some cases. What I heard was, “If the men in power can treat women as if we’re sexual minorities, imagine how much worse they’ll treat gay men and women who are actual sexual minorities?”

I’ve taken what my mother said, and I can’t tell you how many of my fictional mothers have said that. A man doesn’t have to look very hard at the legislation that has been passing or enacted in many states, banning books in schools and libraries, not only on abortion, but everything to do with LGBTQ content—to what purpose? To deliberately make gay, lesbian, and trans kids feel more alone and isolated than they already feel. That is the motivating cruelty behind that legislation. It’s another way of saying let’s abuse young people who are different.

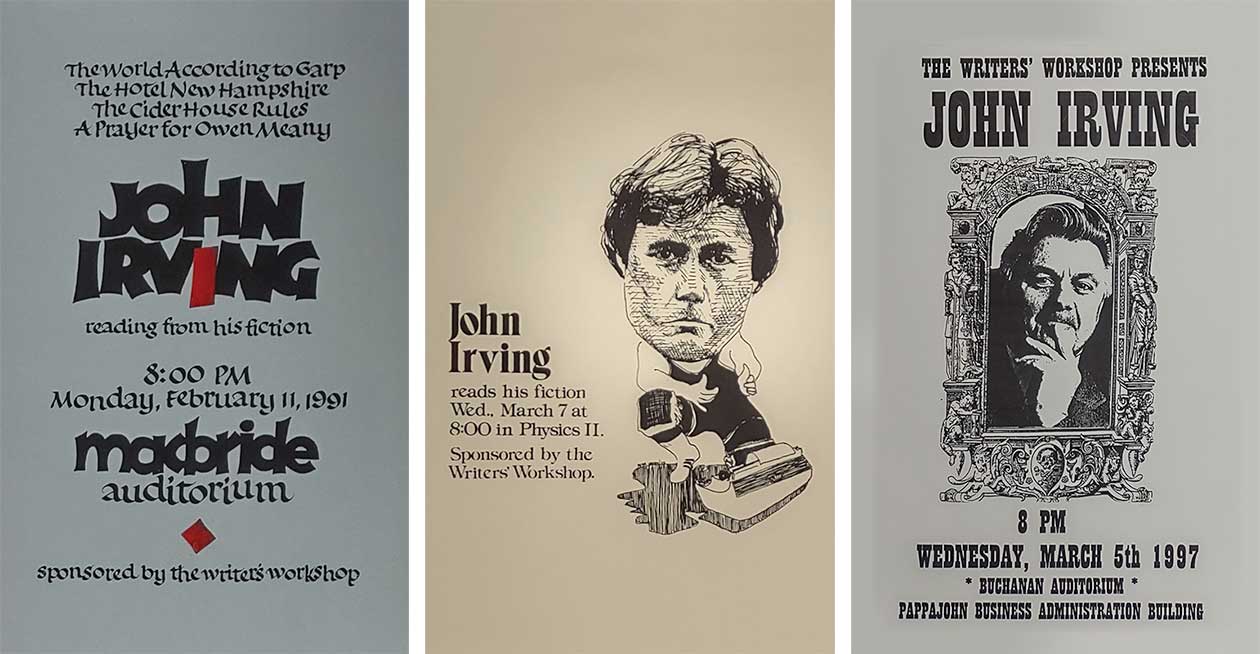

Posters from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop archive show Irving’s past visits to campus.

Posters from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop archive show Irving’s past visits to campus.

Q: You say in The Last Chairlift, “Ghosts know who you are, and what you’ve done.” As one gets older, do the ghosts—the things that have haunted you all your life—get quieter and go away, or do they get louder and more insistent?

A: As you get older, more and more of the people you love are gone. And as Molly in The Last Chairlift says, “Ghosts or no ghosts, we see them.” Let me frame it this way. As a nonreligious person, ghosts are as far as I can credibly imagine the so-called spiritual world. People I know, who are most sane and most rational, have had ghost sightings and experiences. Like A Prayer for Owen Meany, The Last Chairlift is a first-person narrative about someone you miss. In Adam Brewster’s case, there’s a bunch of people.

Q: The Last Chairlift puts us firmly back in John Irving country, providing, among other pleasures, a missing father found. Did you feel, when you finished The Last Chairlift, a sense of, “Okay, I’m done, I can spike the ball, I’ve said what I have to say, and that’s good enough”? Or do you always have the next one pulling you forward?

A: I always have the next several ones. When I deliver a manuscript to my editor, knowing it will be six weeks, two months, before it comes back to me, that’s plenty of time to look at the stacks of notes I’ve been taking, to look at the four or five trains in the train station, and pick the next one. And then I’m back to single-mindedness, focusing on mostly to do with the ending. In many cases, I have as much as the whole last chapter written first. Then I start thinking about the beginning. What happens to everybody? Where do we want the reader to start with these people? By the time I’m promoting a novel that’s being published, I want to have written the first four or five chapters of the next one, waiting for me to go back to. I can pick up the ball where I left it.

But what a relief it is to realize, as I’ve said about The Last Chairlift, it really is the last long train in the station. All the other trains look a lot shorter to me.