Fragments: Memories of My Father

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

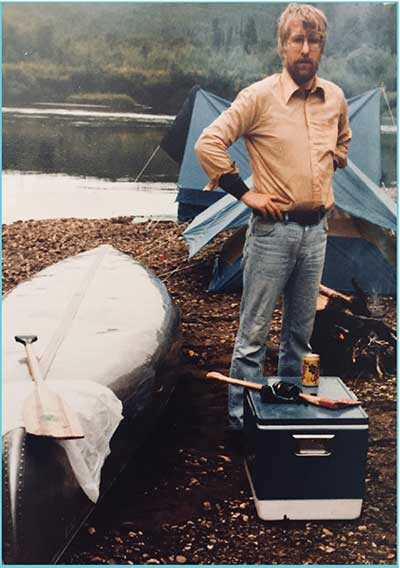

Iowa physics professor Christoph Goertz in Alaska, 1980.

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

Iowa physics professor Christoph Goertz in Alaska, 1980.

Long before school mass shootings became an almost routine part of the American experience, a student with a legally purchased weapon and no prior criminal or mental health record went on a premeditated rampage through the University of Iowa, killing five, paralyzing one, and then turning the gun on himself. My father, Christoph Goertz, was among the victims. He was 47 years old, in the middle of his life and an illustrious career.

My father and I were very close: we shared the same birthday and people said I took after him. He was a role model, confidant, and mentor who supported and challenged me, talking me through problems and piercing through any of my self-deceptions with scientific precision. Even after leaving home for college, I would consult him on personal matters, and his brutally honest opinion generally guided my decisions. After his death I realized to what extent I had depended on his sage advice. It took me a long time to disentangle the person he wanted me to be from the person I had to become on my own.

I loved my father's adventurous spirit, his inquisitive and critical mind, and his great capacity for enthusiasm. He was interested in many things and his passion was contagious. My fondest memory is of him telling stories. He was a masterful storyteller who could transform the boring highway on long road trips into a monster's endless tongue, pulling our family car into a treacherous adventure. My father was also a fabulous reader who introduced us to The Hobbit, Watership Down, and The Call of the Wild. He gave each character such a unique voice and accent that I can still hear his lisping rendition of Gollum in Tolkien's trilogy. My father could also be very funny, both sarcastic and goofy. He was a big Monty Python fan and came up with his own silly walks or hilarious outfits and hairdos to make us laugh. He knew how to throw a party, loved cooking and entertaining. We would often assemble in the kitchen to watch him make a bechamel sauce or his unbeatable zabaglione dessert.

PHOTO: DAILY IOWAN

Police respond to the Nov. 1, 1991, campus shooting.

PHOTO: DAILY IOWAN

Police respond to the Nov. 1, 1991, campus shooting.

Now at 55, I am older than my father was when he was killed and I have lived more than half of my life without him. In the years following his death, as I was trying to forget what had happened to him, I was afraid that I would forget him, too. And certainly, he is not as present as he once was. But as a parent now myself, I find his ways often coming back to me, and I seem to recognize bits of my father in my own son. If I ever want to reconnect with him, I just put on Keith Jarrett's soulful Kölner Concert and find myself right back in the concert hall where my father and I heard the jazz pianist play more than forty years ago. Or I sit down at the piano myself and can easily imagine him listening, urging me to play just one more piece.

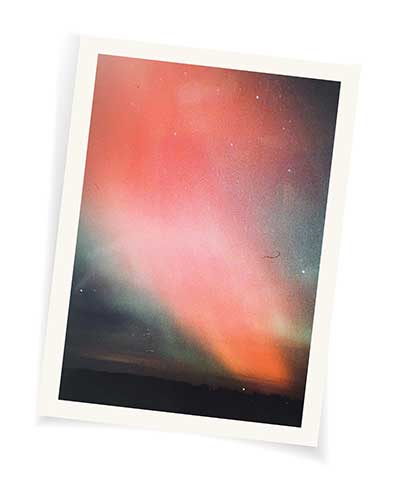

As close as I felt to my father, I didn't end up sharing his fascination with science. I'm more of a humanist, but I respect the scientific approach and recognize that science is key to solving our planet's most urgent problems. In retrospect, I regret not having listened more to his explanations of the natural world. While he described the northern lights he witnessed on research trips to Alaska and Norway as highly charged particles released by solar storms colliding with the earth's atmosphere, I would imagine a paintbrush swooping across an enormous canvas. Finally, I experienced the fantastic aurora borealis myself—exactly a week after the shootings and a day after the community memorial service for the victims. As my mother and I were taking an evening walk, several cawing crows drew our attention up toward a most spectacular display of reds and greens in the sky. Our immediate shared reflex was to laugh and to interpret the light show as a cosmic farewell. Undoubtedly, my father was smiling down at us, mocking us for being so superstitious, but embracing the aurora as a parting signature was, and still is, comforting. It was as if my father was using the scientific vocabulary of the skies to reach out to the magical thinker in me. Even the scientific community drew a connection and regarded the auroral display over Iowa as a "fitting tribute" to colleagues who had spent years studying the phenomenon. Today, a plaque outside the so-called "Aurora Room" in the physics department is dedicated to the memory of its four victims: Christoph K. Goertz, Dwight R. Nicholson, Robert A. Smith, and Linhua Shan.

The mass shooting of Nov. 1, 1991, happened while I was in graduate school in Austin, Texas. I had just been home to Iowa City a week earlier for the Thanksgiving break during which my father and I had a difficult conversation about my studies. I was having doubts about continuing and he was very frustrated by my desire to give up. It was a heated discussion to be continued over the Christmas holiday which, of course, never came to be. That unfinished conversation may have been part of the reason I kept on studying; I just couldn't let him down.

I don't remember who told me that my father had been killed. When I broke down, my dog came and did a wonderfully primal, protective thing: she quietly lay on top of me, her weight eventually calming me down.

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

Karein Goertz took this photo of the aurora borealis on Nov. 8, 1991, a week after her father's death.

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

Karein Goertz took this photo of the aurora borealis on Nov. 8, 1991, a week after her father's death.

I first heard about the killings on NPR news: "Gang Lu, 28, a graduate student in physics from China, reportedly upset because he was passed over for an academic honor, opens fire in two buildings on the University of Iowa campus. Five University of Iowa employees are killed, including four members of the Physics Department; one other person is wounded. The student fatally shoots himself." It was the top story on the 5 o'clock news and just over an hour after the shootings, so they hadn't released the names yet. I experienced momentary panic, but calmed myself down with rationalizations: the department was large, and the chance that my father would be among the victims was more unlikely than not. I tried calling home and initially no one answered. Eventually a stranger picked up and called for my mother, but she didn't come to the phone. I could hear a lot of people in the house and began suspecting the worst. I don't remember who told me that my father had been killed. When I broke down, my dog came and did a wonderfully primal, protective thing: she quietly lay on top of me, her weight eventually calming me down. Years later, when I had to put her to sleep, I remembered that moment.

What followed was a series of very calm and methodical, almost automatic actions: I called the German Department, where I worked as a teaching assistant, letting them know that I would not be coming in the next week. After that, I called the airlines to book a flight to Iowa City. When they said they would need a death certificate to warrant a special airfare, I told them to check the front page of next day's newspaper. Finally, I left messages on the answering machines of close friends, asking them to come over as soon as possible. Eventually friends started flocking in and the apartment filled with people. At that point, I started being overcome by alternating feelings of terror, disbelief, numbness, confusion, calm, and anger. Over the course of a few hours, I got used to these cyclical waves, and whenever I'd start imagining the worst things—how my father was killed, what he may have felt, how long it took him to die—I would force myself to think about something else. I don't remember much about what was said that evening, but I remember feeling immensely soothed by the company of these friends. They cried with me, but we also laughed. It was a clear night and I felt reassured by the sky and familiar Orion. For a moment, things were put in perspective: no matter what happens down here, whether we feel like our world is falling apart, the stars and planets are there, unmoved and unchanged.

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

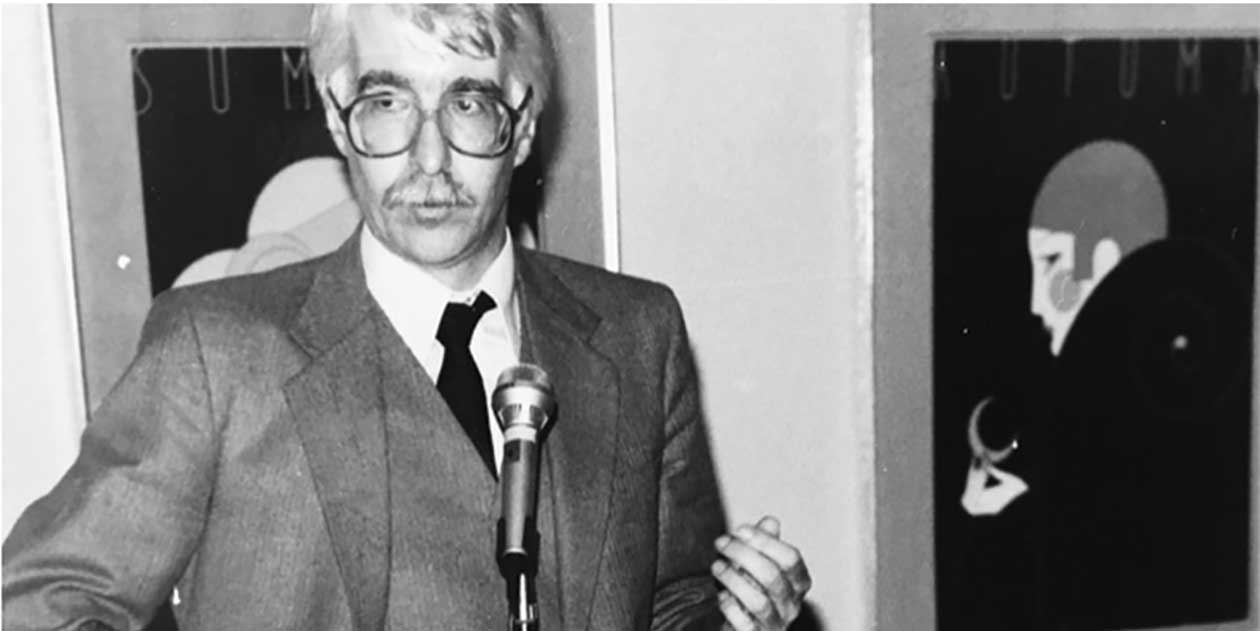

Professor Christoph Goertz lectures in the 1980s.

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

Professor Christoph Goertz lectures in the 1980s.

The immediate aftermath of the shooting is a blur of fragmented memories. Lots of flowers, cards, people stopping by the house. A huge memorial service organized by the university which I attended wearing my father's oversized shoes. Seeing my father's body in the hospital morgue and amazed to find hardly a sign of his violent death. Touching him to comprehend what "dead" is. It must have been much later, my brother and I going to the room where the shootings took place to search for traces. Sorting through my father's belongings in his office, finding poems he'd written, letters, notebooks filled with mathematical formulas.

My mother, brother, and I retreated into our separate emotional orbs. We were each too wrapped up in our own shock to be able to take care of each other. My mother responded with much more anger than I did, wanting to find who was to blame for what happened and launching herself into anti-gun lobbying. I vaguely remember the two of us appearing on the local television news, making a statement against the easy accessibility of handguns. She organized a successful boycott against local stores that sold handguns. My grandmother, recently widowed, had been staying with my parents at the time. She was absolutely inconsolable about losing her youngest son and went around the house asking, "Why didn't he just kill me?" Half a year later, she committed suicide. This was something I could not process.

Since I will never know, I forced myself to believe that my father died immediately: no pain, just a mere instance of surprise, hardly enough time even for regret. I wondered, did he see his life "flash before his eyes," as they say, or did the bullet too quickly destroy that part of the brain that stores memories?

I went into counselling shortly after returning to Austin and graduate school. The sessions were immensely helpful, although I do not remember much of what went on. It was just good to have a familiar place to come to each week to talk about all of the things that were coming up inside that I didn't understand. I often could not remember what year it was or completely phased out and the therapist helped me understand that this was OK, that my mind was taking its time to sort through thoughts and feelings, blocking things out and letting them back into my awareness slowly and incrementally. Since I will never know, I forced myself to believe that my father died immediately: no pain, just a mere instance of surprise, hardly enough time even for regret. I wondered, did he see his life "flash before his eyes," as they say, or did the bullet too quickly destroy that part of the brain that stores memories? Was the explosion inside his head enough to drown out the sound of the other shots fired? I also thought about the killer and wondered how someone could be so filled with hatred to actually kill another human being. The idea that he spent months premeditating this murder while continuing to interact with his future victims was extremely perplexing and disturbing to me.

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

The author with her father, Christoph K. Goertz, in 1969.

PHOTO COURTESY KAREIN GOERTZ

The author with her father, Christoph K. Goertz, in 1969.

At the time, the University of Iowa was one of the nation's top five universities in space physics. When Gang Lu, my father's doctoral student, went on his shooting spree, he took out three core faculty members in magnetospheric physics, thereby wiping out that part of the department. How my father's death impacted the science community is probably best answered by people in his field, but considering that colleagues described him in Physics Today as "one of the most outstanding space plasma theorists of our time," I can only imagine that it dealt a significant blow to the community. He helped interpret data from space missions to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune and, at the time of his death, was "pioneering an entirely new area of space plasma physics concerned with the interaction of dust with hot plasmas." Famed professor James Van Allen, who first recruited my father to the University of Iowa in 1973, is said to have considered him his favorite theoretical collaborator.

Five years after the shootings, we were still reeling from the after-effects of this rupture, trying to regroup as a family, but still feeling disoriented and fragmented. My mother sold our family home, left Iowa City, and embarked on a new career. She was going through chemotherapy for a cancer she believed was triggered by the shock of my father's murder. I was finishing my graduate studies, writing a dissertation on Holocaust literature and the impact of trauma on memory. My brother was studying architecture in Miami, arriving just as that city was recovering from the devastation of Hurricane Andrew.

Ten years later, my mother had moved back to Germany. Her cancer was in remission, she was working as a Feldenkrais and Alexander Technique practitioner in Berlin, and launched herself into the all-consuming project of renovating an old house in Italy. I married, held a teaching position at the University of Michigan, was leading student study trips to Berlin, and was fully engaged in my career. My brother was working in an architectural firm in Miami.

Today, my mother is a vibrant, physically and intellectually active woman with a large network of friends and many different interests. She is an inspiration to me: a model of aging well and living life with gusto. I still teach at the university and have a long-term partner who is also the father of my 13-year-old son. I tell him stories about his grandfather and he has long known how he died. My brother recently relocated to Switzerland where he continues to work as an architect. Interestingly, as he approached and then surpassed my father's age, he has become more like him in his mannerisms and interests. We get together as a family once a year in my mother's house in Italy, and while we do not often talk about my father, he does feel present among us.

In the three decades since my father's death became a statistic, the incidences of mass shootings have accelerated and our response to them have a terrifying déja-vu.

All of us have been able to carry on with our lives. What happened almost 30 years ago feels distant and contained, for the most part. It does come to the foreground whenever there is another mass shooting or when people argue for the unimpeded right to bear arms. Gun control should be a straightforward issue: If we want less gun violence and mass shootings, we need stricter gun laws. I am hopeful that momentum gained from such necessary protests as the March for Our Lives or initiatives tracing the connection between politicians and the NRA will eventually change attitudes and policy toward guns and gun control in this country. But even though hope is tenacious and one our best human traits, it wears thin. In the three decades since my father's death became a statistic, the incidences of mass shootings have accelerated and our response to them have a terrifying déja-vu. Haven't we already reached the tipping point?

To confront these recollections again, I opened a box filled with documents I hadn't looked at in well over 20 years: letters, photographs, newspaper clippings, scientific papers, a death certificate, my grandmother's suicide note, program notes from the memorial service, my dream diary, the murderer's statements, Jo Ann Beard's story "The Fourth State of Matter" from The New Yorker. I've long feared this Pandora's Box with its blunt truths: "Manner of Death: Homicide. Date of Injury: 11/1/1991. Describe How Injury Occurred: Shot with 38 Caliber Revolver. Immediate Cause of Death: Gunshot Wound to Head. Signed by Johnson County Medical Examiner."

I wasn't sure if opening the box would unleash things I couldn't put back in again. And although the notarized Certificate of Death filled me with a renewed feeling of dread, I was surprised by the overall sense of quiet I experienced in revisiting these remnants from what seems like so long ago. The many beautiful condolence letters I wasn't able to fully appreciate back then have allowed me to buttress the image of my father with memories of others. I am reminded that my father did not believe in heaven or an afterlife; instead, he always said we live on in the memory of others. Writing about him now for the book If I Don't Make It, I Love You with more than 60 narratives from survivors of 50 years of school shootings, seeks to do just that: to recall the lives and make sense of the deaths of those who were abruptly and violently torn from us, in the hopes that each account can transcend the specifics of the individual story and give solace or guidance to others who may have to face the ordeal of a mass shooting, and its lifelong aftermath.

Karein Goertz (88BA), PhD, teaches German and seminars in English at the University of Michigan. This essay is excerpted from a piece first published in If I Don't Make It, I Love You: Survivors in the Aftermath of School Shootings, edited by Amye Archer and Loren Kleinman (Skyhorse Publishing, 2019).