Inside Voices: A Prison Choir, My Mother, and Me

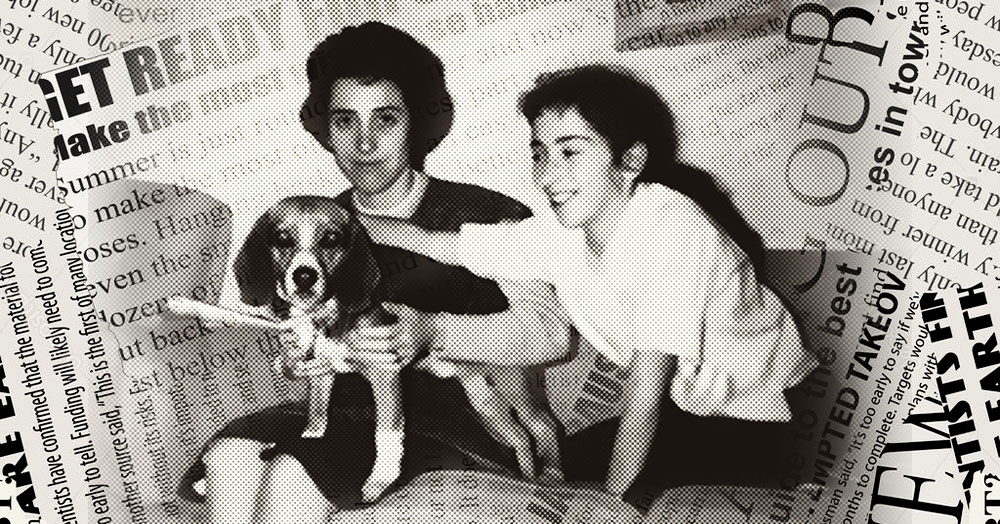

PHOTO COURTESY AMY KOLEN

Amy Kraft Kolen is pictured at right with her mother and dog Buster around 1962.

PHOTO COURTESY AMY KOLEN

Amy Kraft Kolen is pictured at right with her mother and dog Buster around 1962.

As we outside singers filed into the rehearsal room that first choir practice of the season, a month before my mother’s stroke, inside singers from the songwriting workshop that preceded rehearsal were arranging folding chairs for our sections. A couple of guys steered the rolling cart holding guitars, handheld percussion instruments, and a banjo closer to the piano, while others organized musical scores.

“How nice,” a friend had said when I told her I’d joined the Oakdale Community Choir. “You’re in a choir with your mother,” she said, confusing my mother’s home in Oaknoll Retirement Residence with Oakdale prison. An understandable mistake. Both have the same number of letters, both begin with the word “oak,” and both incorporate a landscape element into the name.

Everyone looked up from their tasks and smiled in greeting when they saw us, some waving hello. Once we were all assembled, Mary invited us to introduce ourselves to someone we didn’t know in the few minutes before we warmed up.

Self-introductions, never easy for me, typically incited mild anxiety when I was compelled to mingle with people I’d never met, and I’d never met any of the inside singers, had never knowingly had a conversation with anyone who’d been in prison. I didn’t want to hover around Andy, who was talking with some inside singers he hadn’t seen since the last concert, the one I’d attended in May. And I didn’t want to hang on the sidelines doing nothing, feeling like the last person chosen for the softball team (as was the case the only time I played a team sport, in sixth grade), waiting for someone else to make the first move.

I surveyed the beige, windowless walls, unadorned save for the large clock on the wall, like the clocks on the walls of my school classrooms when I was a kid, and trying to look busy, bent towards the industrial-sized cooler near the door and poured some water into a Styrofoam cup. When I turned back to face the room, a young man, around 28, my son’s age, was walking in my direction. About my height, with shaved head and horseshoe mustache, he wore tattoos in black ink of what looked like crosses superimposed on barbed wire wound around his neck and forearms. A laminated card with his name and prison identification number was clipped to his navy T-shirt.

“Hi,” he said, smiling, hands in his pockets, allowing me to initiate a handshake, if I wished, per prison rules. “I’m Zach.”

I introduced myself, extending my hand, which he clasped between both of his. “This is my first rehearsal,” I said, “the first time I’ve ever sung with a group. Any tips on how to get started?”

“Sure, no problem. Let me show you the book I’m using about learning how to read music.”

I followed him to his chair in the bass section, and we chatted for a few minutes while he flipped through the book, pausing at certain pages he found particularly helpful. “You should ask Dr. Cohen if you could borrow a copy,” he said, just before we all gathered into our separate sections.

That wasn’t so bad. I’d just had my first conversation, albeit brief, with an inside singer. And it wasn’t any more or less awkward than talking to someone who wasn’t incarcerated. I thanked Zach for his help, took a chair with the altos, and in no time lost my place in a rhythmically complicated “I Heard It Through the Grapevine.” As the voices harmonized around me, the screeching in my head got louder: “Two note heads and stems on the upper staff? How can I tell which one I’m supposed to sing? What if they don’t line up vertically? How will I know what to do? Why are some of the notes’ stems pointing down? Oh, I get it! Those are the altos.”

For the 90 minutes that we rehearsed, I was forced to concentrate or risk getting lost in the music. I was forced to focus—and I liked having my mind shut up so I could concentrate. It felt good to stretch my lungs, vocal cords, and comfort level, which included singing songs that I never thought I’d add to my repertoire.

As a Jew, I initially feared that the more obvious (to me) Christian songs, which I didn’t know nor think I’d care to learn, would eventually keep me from sticking with the choir. Along with discussing with Michael the issues revolving around safety and singing in the prison, the content of many of the songs figured in our talking through my decision to continue participating after that first rehearsal. Though our repertoire did include the Motown classic, “Grapevine” (and I admit that I wondered about its lyrics, sung in the context of a prison choir, about a man’s finding out that his girlfriend is cheating on him), during my first season with the choir, songs with seemingly religious themes loomed large—from the Romantic composer Cherubini’s “Veni Jesu” to an inmate’s song adapted from Psalm 30, to another incarcerated songwriter’s piece that thanked the Lord Jesus for his staunch happiness, regardless of situation.

Initially, I thought the words to such pieces had nothing to do with me. Throughout my life, I’d bleeped out all references to Jesus in the prayers and hymns that dominated most of the funerals and weddings I’d attended, and substituted the words love or higher power in my mind. But after a month of rehearsals, I realized that the music and emotional content of some of these songs worked in tandem to evoke in me genuine and positive responses.

Despite the distraction of mechanical voices from nearby PA systems blasting announcements for inmates into this wing of the prison, “The Prayer of Saint Francis” lyrics held particular significance after my mother’s stroke. The words helped me attend to the task that immediately waited outside these walls: being a reliable and caring advocate for my mother while she was in the hospital, and possibly after she was released.

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace…

Where there is darkness, let me bring light…

Where there is sorrow, let me bring joy…

Not so much seek to be consoled as to console…

Where, I asked myself, is the divisiveness in wanting to be “an instrument of peace”? Why would “not seek[ing] to be consoled,” but instead trying to console and offering understanding and support be limited only to those who consider themselves Christians? And even if I didn’t yet hit each note correctly, how could I not love the altos’ “amens” in the last eight measures, the elegant way the notes flowed down the scale, how they crescendoed then quieted, in a meditative, natural sealing of the singers’ wish for a spacious and generous spirit?

“Nicely done, ma’am,” said Tom, the inside tenor beside me, as we put our scores back into our folder at the end of the piece. I thanked him for his gracious comment. Who wouldn’t want to feel this way?

In addition to maintaining focus on the lyrics and rhythms, I had to constantly attend to proper ways of behaving towards the inside singers, especially important when we broke into small groups for informal discussion. During our volunteer orientation, we were instructed not to ask insiders about the offense that landed them in prison. If they offered that information, we had to end the conversation. We weren’t supposed to ask about their families, past employment, how they envisioned their futures.

Which meant I had to think before I opened my mouth. Deliberately present and staying in the present, in the moments before choir ended, I asked Tom about his contribution that month—an article on the inmate council—to the insider-edited newsletter, a publication in which contributors can voice their concerns in a venue that outsiders rarely see. He grinned. “Wow!” he said. “I’m not invisible! You really read it? I don’t think many of the guys in here even looked at it for a minute.”

In the car after rehearsal, driving back to the hospital, I reflected on my interactions with Tom that day and with Zach during my first rehearsal and with everyone else I was meeting in the choir. Being vigilant didn’t necessarily mean being unable to relax. Rather than the “monkey mind” of worries that I’d brought to my first prison experience as a guest at the spring concert, if I instead approached the choir with “beginner’s mind”—an expression I heard in a yoga class years ago, referring to freeing oneself from preconceptions, starting from a pure childlike place and keeping an open, eager mind—perhaps I could relax into the spirit and energy the group generated.

As with any other choir, while we sang together as a group, each of us was an individual—each continually learning what non-judgment, acceptance, and love are and how to bring those elements forward in our lives. An ongoing challenge. A life’s work. And I briefly considered the possibilities of applying the new (for me) concept of ubuntu, of “communal connection,” that the choir was nourishing in a very small, personal way towards my interactions with my mother, of being available to her and exploring what the potential for new connection might be—though I wasn’t yet certain if the old rules and who I thought I was relating to were gone.

UI Nonfiction Writing Program graduate Amy Kraft Kolen (73BA, 00MFA) is an Iowa native who lives in Estes Park, Colorado. Among her many works, her essay “Fire,” about her family’s connections to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, was published in The Best American Essays 2002, and the essay “Moenkopi Dance,” about a visit to the Hopi Cultural Center, was shortlisted in The Best American Essays 2009. This excerpt comes from her new book, Inside Voices: A Prison Choir, My Mother, and Me, which was published this past fall by Ice Cube Press, an independent press run by Steve Semken (87BA).

While in Iowa, Kolen volunteered for four years to sing at a prison alongside community members and inmates through the Oakdale Community Choir. Though the program ended in 2020, Kolen’s memoir shares how the experience enriched her perspective on life and helped improve her relationship with her mother, whose health was rapidly declining after a massive stroke.