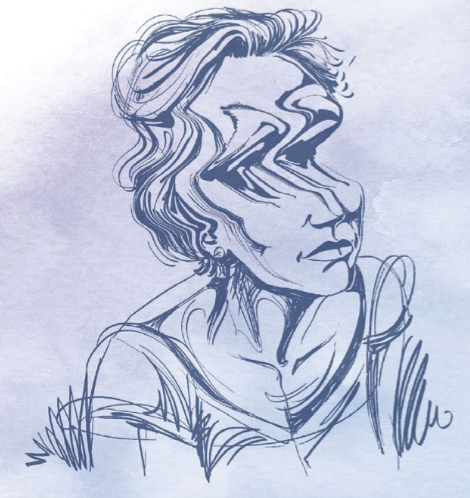

The old woman stands with her knee bent, her foot propped on the retaining wall, her belly thrust out, her coffee cup clutched to her chest. She's the kind of woman who, when she stands with one hand on her hip, or adjusts her trucker hat over her short gray hair and plastic-framed glasses, appears tough but cheerful, distinctly unfeminine. In her mind she still seems to be an athletic woman of 40 and not a round senior with a magenta sweatshirt tucked into the high waistband of her tapered stretch pants, her ample thighs funneling into calves and then tiny feet in pointed black leather shoes. It's difficult to imagine she ever took men as lovers but the girl knows she did, she's told her.

She's told her about meeting men folk dancing, bringing them home. She's told her about how sometimes the doorbell would ring Sunday morning and the woman would turn to the man beside her and say, "That's my father, here for breakfast. You can join us or you can leave, the choice is up to you."

There was another story she'd told once but not repeated:

"My dad asked his secretary. She'd heard of a doctor who would do it."

"How old were you?"

"Oh, mid-twenties. I called him. He wanted to come to my apartment, I didn't think I could say no. He forgot his watch. After all that he didn't take care of it, I still ended up having to go to Mexico, but my dad came with. My mom was on a trip to Europe, thankfully. I never told her. My dad insisted on coming into the room where they would be operating. He saw the tools were dirty and he yelled at the people until they sterilized them. He saved my life."

"I can't believe that American doctor! Couldn't you have reported him to someone?"

"What could I do? I had asked him to do something illegal. I sent the watch to his house, I hope his wife opened it."

One day the old woman shows the girl a silver squash blossom necklace, tells her it had been her mother's, and then it goes back into the box where it has been hidden. The girl throws a necklace-appropriate dinner party and invites the old woman and the woman's neighbors, two retired men, friends from when the dementia was only a feeling of uneasiness brought on by a backyard so overgrown it was impenetrable. It is the neighbors who found and hired the girl (she is paid by the old woman's accountant) but they have been taking the old woman grocery shopping and to the doctor's appointments they schedule and filling her prescriptions long before the girl was hired. The old woman wears the necklace and it is admired, and then, back into the box.

The girl tries to tell herself that there is no tragedy in the lack of next-of-kin. The old woman knew she didn't want children or marriage, she struggled and succeeded at careers in male-dominated fields, she traveled, built a darkroom, wrote an unpublished memoir, went dancing every weekend that she didn't go skiing. The girl's affection for the woman is bound up in this independence, in the books about the Black Panthers that appear randomly on her crowded bookshelves, and the faded and stained NARAL sign in the basement, saved from some demonstration long before the girl was born. One day the girl says, "Things are easier for women my age because of work you did. I want to say thank you."

"You're welcome," the old woman says, simply and cheerfully. The girl is touched by the way the old woman has accepted her gratitude as due. She thinks about how she prepares meatloaf for the woman, and changes her sheets, and puts lotion on her pale and mottled back to sighs of pleasure—we all need touch—and she thinks of watering the old woman's plants, scooping the cat litter, mopping the kitchen, and, both Christmases of their acquaintance, helping bake the woman's mother's panettone recipe, how the girl had zested lemons while the old woman had chopped walnuts in an old wooden bowl, completely round so it rocked on the counter, using an old metal utensil with curved blades to curve hard against the wooden bowl's sides, so perfect for the task, a rare flash of determined competence in the even line of the woman's mouth. Old memory.

The girl thinks of the quiet domesticity of these tasks and it seems perverse that she should make so little use of the old woman's blows against the glass ceiling but fitting that she can respectfully offer these womanly, homey tributes. Who else but one's own might tend to the aging soldier? Who else might sit in the twilight attentive to the battle tales? But then she thinks of the neighbor men, of their tidy files labeled with the old woman's name, how they were the ones to find a plumber to fix the shower, and a crew to clear the yard, and had the furnace serviced, and a million other tasks that usually fell to adult children or siblings who still found it all too much. They are not paid as she is, and when the four of them go out for coffee she is the one on the clock. It is hard, in this light, to romanticize her feminine role.

Packers and movers have been hired but the old woman doesn't understand. She has been packing in her crazy, determined way—taking down the shower curtain weeks before the moving date so it won't be wet when packed, putting dirty, broken lawn furniture in the middle of the living room. The rest of the time she is grieving. She tells the stories of the deaths of her mother and father, over and over. She tells the story of her mother's miscarriage, the brother she never met but has been mourning nearly her entire life. She tells the story of buying the house, of moving in, of the huge potluck she threw decades ago, with speakers propped in the windows and folk dancing late into the night in the enormous yard. The stories are garbled and messy, she repeats details, she loses words, and the timelines are wild and surreal—she was 20, she was 60, she was 12, she was in college. The girl never argues.

The woman is being moved Monday, it is Thursday. The girl and both neighbor-men accompany her to see the facility. The girl is impressed with the apartment, it has skylights and a small private deck facing trees, the ceilings are high. The woman is withdrawn and belligerent. She says, "I don't want to be here! I hate it!" The girl says, "I know you are upset—" and the woman literally stomps her foot and says, "I don't want to be here! I hate it! I hate it! I want to go home!" The room is very tense. One of the neighbor-men says, "I know you do." The woman says, "You'll get to go home, and I won't. I'll be here where I don't know anyone! It's so easy for you." She doesn't understand that the neighbor-men researched and visited many facilities, met with all of the managers of the homes. They've been working with the moving company and the realtor who will sell the house. They've made sure the woman got her TB test and the cat has been screened according to the health policies of the facility. They are tired, but who would do this if they didn't? That isn't reason enough for most neighbors but it is for them. His answer can't reach the old woman, in the state she's in, but it reaches the girl. The woman's sadness is painful but over the weeks and months, the girl has come to feel a degree of remove, as though her empathy is still there but worn smooth from the constant friction. This kindness from the neighbor-men, however, in the face of the woman's utter incapacity for gratitude, it overwhelms the girl.

She wishes that the woman could feel, as she does, the power of this kindness.

The girl makes her a hamburger when they get home and they sit in front of the television with The Golden Girls on. It feels like it could be any ordinary Thursday night, and the old woman is in her pink chair, her head in the greasy groove, her lean, gray tomcat sleeping in her lap. Calmly, the old woman says, "What did you think of the place today?" The girl says, "Well, I know it's not home, but it's really pretty nice." The old woman says, "I feel bad about what I said there." The girl says, "You were upset, don't be too hard on yourself." The woman laughs a little bitterly, with a self-knowledge that is increasingly rare now. She says, "I was disoriented. I didn't know where I was." The girl says, "Did that scare you?" The woman says it did. They say these things to each other a few times, because clarity, when it comes, is a slippery thing; it needs to be fondled and dropped a few times, and even then whether it will stick or not isn't guaranteed.

Lila Savage, a Minneapolis native and former Stanford University Stegner Fellow, is in her first year at the Iowa Writers' Workshop. With years of experience in elder care, she nds inspiration in the lifetime experiences and wisdom of the older generations. Lila's 91-year-old grandmother just moved in with her.

This is an abridged version of "You're Welcome." The piece published in its entirety in the summer 2016 Threepenny Review, a literary magazine based in Berkeley, California.