On the overhead screen, historic photos and old film footage project images of careworn miners—their furrowed brows caked with coal—and the trappings of their modest, turn-of-the-century lives. It's a muggy summer night at FilmScene independent cinema in Iowa City as moviegoers filter into the screening room, the scratchy recordings of old mining songs steady against a thrum of conversation.

Thomas Clarence Chapman (second from right), Jesse Kreitzer's great-grandfather and the inspiration behind his thesis film. Kreitzer raised the majority of the film's funds through a successful Kickstarter campaign, a film tour, and other grassroots support.

Iowa, the land of corn and pigs, seems an unexpected place to ruminate about coal mining. Yet, in the early 1900s, it was the state's No. 2 industry and particularly common among the hills of south-central Iowa. A coal miner's work proved laborious, dangerous, and burdened with a certain despair. To gauge the dangerous fumes of a tunnel, they often carried caged canaries into the darkness. If carbon dioxide and other noxious fumes proved too great, the birds would succumb before the miners—a warning that they should promptly evacuate the tunnels.

Jesse Kreitzer is a coal miner's great-grandson. He stands just inside the doorway, shaking hands and exchanging pleasantries with the crowd. He wears jeans and a crisp denim work shirt over a white v-neck tee, unbuttoned with the sleeves rolled to his elbows. His reddish beard is trimmed and comes to a dull point below his chin, like a spade.

In just a few short moments, nearly two years of hard work and obsession will culminate with the debut of Kreitzer's MFA thesis film, Black Canaries. A short period piece set in 1907, the story draws inspiration from his maternal great-grandfather, Thomas Clarence Chapman (TC, or Chappy), who owned and operated the Maple coal mine near Albia, Iowa. Kreitzer uses imagery to weave a tale about a family's struggle after a mine collapse, and, in the process, brings attention to a lesser-known aspect of Iowa's heritage.

He'd pondered the mining idea for some time before arriving at the University of Iowa three years ago to study film. He knew about Chappy and that his maternal grandmother, Ruth Ruckert, had been born in March 1921 and raised in Maple, Iowa. Although long fascinated by family history, Kreitzer says these tidbits were about all he knew of his Iowa roots. Driven to combine his love for film with this aspect of his family tree, Kreitzer packed a U-Haul trailer, left Boston and a job in local television, and drove cross-country to Iowa City.

"I knew this was a privileged time to study and connect with my family," says Kreitzer, 15MFA, who previously created a documentary on the restoration of an old family film of his father, but viewed his time in Iowa as a chance to explore his mother's genealogy. He connected with long-lost family members who shared their photos and artifacts, and turned his attention to his great-grandfather's backbreaking trade.

Jesse Kreitzer, right, on set. In addition to his Iowa degree, Kreitzer has a bachelor of arts in visual and media arts from Boston's Emerson College.

Even though Iowa isn't commonly regarded as a coal state, mining once was an important part of the economy, especially along the Des Moines River Valley between Keokuk and Fort Dodge. The industry began in earnest in eastern Iowa around 1840 and exploded within 20 years thanks primarily to the railroads. Mining changed the face of Iowa, as skilled laborers and their families flocked here from England, Wales, Scotland, and Eastern Europe. African-American mine workers also migrated from the Southern states to work in these new Northern mines. Most of the "native Iowans" who became coal workers were the sons and grandsons of these immigrant miners, says John McKerley, a historian with the UI Labor Center's Iowa Labor History Oral Project. They'd grown up in mining camps, essentially "company towns" with slapdash houses, a store, tavern, and sometimes a school.

Kreizer's great-grandfather worked in the mines his entire life. After the death of his father, Chapman left school at age 11 to serve as a door boy who helped air flow through the shafts. Monroe County, where Chapman owned and operated the Maple coal mine, was home to a number of mines and mining communities. The Maple mine and mining camp was active from 1917 to 1924, and, at its peak, yielded 100 tons of locomotive coal for the Northwestern Railroad per day. The 1920 federal census shows the men, women, and children living in the Maple coal camp came from throughout the Midwest and South, as well as from Croatia and Finland. In 1924, a dispute between mine officials and the railroad ended in the mine's closure due to a market decline. Mining plummeted across Iowa as railroads began buying coal from other states like Illinois and Kansas. The Maple mine was abandoned and so was the town. Its 103 houses, the company store, and the school stood empty, and the entire community was torn down in 1935.

"These were boom towns," says McKerley, noting a steady decrease in Iowa mines by the 1920s and the loss of the adjacent communities that grew up around them. "Once the coal was gone, they didn't have any reason to exist."

Iowans who had been raised on mining found jobs in other industries and McKerley says that this is perhaps the strongest example of Iowa's mining legacy. Mining is exceptionally difficult and dangerous work, and these Iowans worked together. "They found solidarity to deal with the danger and the deprivation they experienced," McKerley says. "When they or their children and grandchildren moved on and became the foundations of many of our Iowa cities and towns, they took this legacy of solidarity and perseverance with them. That legacy is alive today. [In that respect], the mines did not just disappear."

During his research for Black Canaries, Kreitzer visited the Monroe County site of the former Maple Coal Mine. There he met Bill Crall, who has lived in Lovilia, Iowa, for more than 50 years and owns the land where the Maple mine once stood. Crall gave Kreitzer a tour of his property; a pile of shale and a pump that had once been used to keep water from soaking the mineshaft were the only physical signs of the past. Crall also explained how some miners had come back wanting to investigate the old tunnels. "When they went down, the old coal cars were sitting there loaded and the picks and shovels were just leaning against the mine walls," he says. "During their work shift, they must've found out the mine was closing and they just walked out."

Stories like these and of the struggles of coal-mining families gave Kreitzer fragments, anecdotes, and impressions from which to start production of Black Canaries. He described his project to financial backers in this way:

In 1907, the Maple coal mine collapses, blinding the Lockwood family's youngest boy and killing the hauling mule. To keep his surviving family warm against the winds of the vacant prairie, Father has no choice but to continue drudging the depths and extract coal from the ruinous mine.

As his pickaxe wails far below earth's surface, he discovers a rare mineral coveted by a secret society of the town's miners. When distilled above flame, the mineral releases an intoxicating spirit that gives men brief reprieve. Father's induction into the inner circle breeds a consuming desire to exhume the family mine for its riches, as his wife and children witness the destructive bond between people and the land they are captive to.

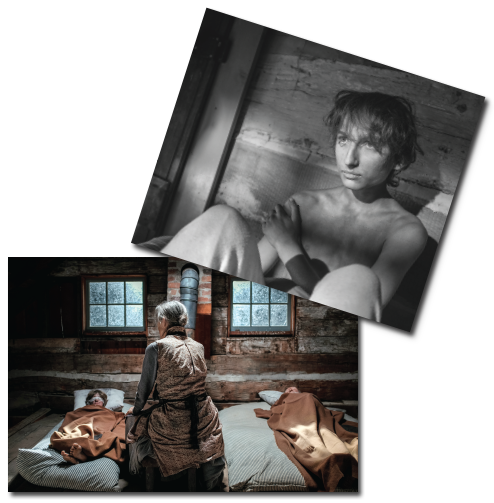

Production stills from filming are pictured. The cast mostly included talented individuals from Fairfield, Iowa, and featured Iowa City City High drama student Andrew Stewart (above).

Through imagery, Kreitzer set about conveying the notion that the very work a person loves can destroy a life and soul. The family at the heart of the film represents the canary bird, caged in oppression. In one scene within the Lockwood family's sparse home, covered in coal dust, the miner stares at the coal burning in the potbelly stove, transfixed by the mineral that is the source of his family's suffering and survival. The historical nature of the story meant every detail needed to be managed, from location to costume and set design. Kreitzer found an historic log cabin with the perfect potbelly stove in Keosauqua, built a 30-foot coal mine in Solon, and rode atop a coal-powered train in Boone. He also commissioned a turn-of-the-century style pine coffin and secured an unrestored Model "A" Ford for the final sequence.

A rigorous production scheduled demanded eight 16-hour days for the 16-person cast and crew during a week in early November when the temperature dropped by 20 degrees. Kreitzer shot on 35mm film for an "organic, muddy" analog quality to the images, an approach rarely used anymore as a production medium. At the end of the shoot, he boxed up all the film and sent it to a New York film lab for processing.

When the developed film arrived weeks later and he began to pore over it, he discovered a film that was less folktale and more a study on labor, hardship, and exhaustion—which in many ways mirrored his own production experience. As he describes in his thesis: "The fictionalized portrait of a mining family transcended my genealogical research and evolved into a personal exploration of the creative process, dependence, and fatigue."

In editing, he found himself deleting entire plot-driven sequences and preserving stark, disconnected images. The film wrapped as an exercise in visual storytelling, dependent on pictures rather than dialogue for audiences to interpret as they will.

"His was a very ambitious project: a period drama set in a coal mine calls for a level of production design that is difficult to fit into a graduate timeline," says Mike Gibisser, assistant professor in the UI Department of Cinematic Arts. "Jesse pulled it all together regardless. One of his greatest assets as a filmmaker is his talent as a coordinator, pulling together an array of people, locations, and materials to make something that seems impossible."

After watching Black Canaries and a handful of other Kreitzer films, the friends and family at the FilmScene debut stay to ask questions and express their appreciation for his vision and attention to historical detail.

"You have the eye and the heart for this," one woman tells him.

Kreitzer thanks them all.

Earlier that evening, he'd read from a crumpled list of names—those he wanted to publicly thank for making Black Canaries a reality. Kreitzer says that his film could not have been made without the support of over 270 individual donors, businesses, and organizations that helped him research, produce, and finance the $47,000 film: Entire towns like Maquoketa, Keosauqua, Ottumwa, Fairfield, Boone, and Iowa City. Businesses and groups, including Appanoose County Historical & Coal Mining Museum, the City of Fairfield, the Monroe County Historical Society, the Boone & Scenic Valley Railroad, and the Clinton Street Social Club. The City High drama department and the other avenues he pursued for local talent.

Since Black Canaries wrapped earlier this summer, Kreitzer has been busy preparing the film for the fall festival circuit. He's already planning his next project—a feature film about a hospice worker that takes place over the course of a year.

Looking back on his experience, Kreitzer feels strongly that the film could only have been made in Iowa because of the generosity of locals who gave him access to land and stories, and the historians who helped him understand Iowa's mining history. He feels humbled by the handshake mentality of strangers willing to share their experiences, and the people who worked long hours in uncomfortable conditions for little personal gain.

Not unlike Chappy and the Iowa coal miners of his day.

Featured Films

MFA graduate Jesse Kreitzer is preparing his coal mining tale, Black Canaries, for the upcoming awards circuit. He joins several other UI cinematic arts students who have gone on to have success with these independent films:

Richard Wiebe, 09MA, War Prayer, and Kataryza Plazinska, Chapri, recipients of Jury Awards at the most recent Ann Arbor Film Festival.

Kelly Gallagher, 15MFA, Pen Up the Pigs and Pearl Pistols.

Shannon Silva, 06MFA, Girl Thing: Tween Queens and the Commodification of Girlhood, a documentary about tween girl culture.

Jeffrey Palmer, 12MFA, Isabelle's Garden, appearing at this year's Sundance Film Festival's Short Film Challenge.

Websites

Iowa Labor History Oral Project: http://www.iowahistory.org