The books look like works of art as much as literature. Carefully spread across the library tables, the volumes beckon to guests arriving at UI Special Collections—and these book lovers barely hang up their coats before they rush to run their hands over the worn covers.

In the digital age of the Kindle, iPad, and Nook, these people seize the opportunity to viscerally experience the leather, the paper, and to brush a finger along spines embossed in gleaming gold. They yearn to sit down with others, face-to-face, and talk about the eternal value of books.

A typical meeting of the Iowa Bibliophiles begins with time to touch, examine, and ooh-and-ah over the works a presenter has brought along for discussion that evening. A public program sponsored by the UI Libraries, the Bibliophiles have come together for more than a decade to consider various topics and collections, either from a speaker's personal library or from the time capsule that Special Collections represents.

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

"Our members seek connection and a meaningful experience," observes Special Collections director Greg Prickman, who organizes and moderates the meetings that take place once a month during the academic year in the third-floor reading room of the Main Library. "In our consumer culture, we've lost an understanding about the process of making things. In our group, we discuss not only the books themselves, but the history of how they were made."

By definition, a bibliophile is someone who collects or has a great love of books. Bibliophile clubs exist all over the country, large or small, formal or informal. The UI club's attendance averages about 30 people per meeting, and participants range from the serious book collector to someone who simply appreciates a good read.

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

This year, Prickman decided to refocus the group in an effort to draw more interest and involvement. Past topics have covered books and beyond, including Sherlock Holmes, photography, Iowa radio history, miniature books, and historical maps—featuring a propaganda map from Nazi Germany and shipwreck maps of the Great Lakes. But for the 2013-14 season, the Bibliophiles adopted their first-ever theme: Five Hundred (+) Years of the Book. Beginning last September with a presentation on 15th century books, the Bibliophiles work their way through to the 21st century in May.

Special Collections houses some 250,000 books and millions of documents inherited from famed faculty, alumni, and private citizens seeking a permanent home for their treasures. Anyone can stop by to browse the materials, although their main purpose aims to enhance course instruction in departments across campus, chiefly English, history, art history, religious studies, and the classics. The materials also support the work of UI Center for the Book researchers like Timothy Barrett, who uses the collection extensively to study early papermaking.

The most prized items occupy the Special Collections steel vault. Behind the thick, heavy door with its spindle-wheel lock is a surprisingly large space crowded with a wide variety of rare and unique tomes, including Bibles, children's books, medieval manuscripts, and a prized Shakespeare folio. Some books arrive here through a collector's longtime connections to Iowa; others from people who choose to preserve their legacies at the UI because of its distinguished literary tradition.

For his presentation in September, librarian Pat Olson chose the department's recently acquired 15th century Bible. Bibliophiles marveled at its linen pages, original pigskin binding, and ornate lettering—achieved by the manual process of setting, locking, and inking metal pieces and pushing sheets through a wooden handpress. For his talk on 17th century literature, assistant English professor Adam Hooks brought out the 1632 Shakespeare folio, a tall volume containing the earliest collected works from the legendary playwright. The rare volume came to the UI in 1975 by way of a woman named Snowden A. Fahnestock, who donated it in memory of her father and former solicitor general of the United States, James Montgomery Beck.

"It's by far the most heavily used book in all of Special Collections," says Prickman, tenderly turning the large yet delicate pages. Universal in its appeal, the Shakespeare folio draws vast interest from professors and students. But it's only one of many intriguing artifacts nestled among these shelves, and Prickman graciously offers a tour of some favorites, priceless in their connections to literature's most famous rabbit, an infamous forger, a science-fiction master, and even man's best friend.

To Be or Not To Be?

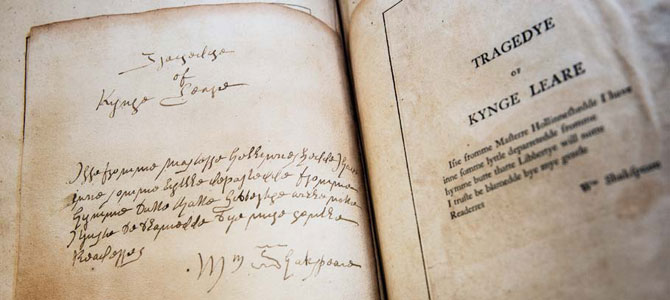

Last fall, as the Iowa Bibliophiles pored over the Shakespeare folio during their discussion of 17th century books, the conversation turned to another interesting artifact in the Special Collections vault—the scrapbooks of a young English chap who committed one of the most famed Shakespeare forgeries.

At the end of the 18th century, William Henry Ireland suffered a very poor relationship with his father, an antiquities dealer in London. One of his father's fondest wishes was to find one of Shakespeare's original manuscripts. So, determined to win his father's affection, Ireland set about fabricating one. He collected all the age-appropriate pens, ink, and paper that Shakespeare would have used and painstakingly hand-copied the playwright's script for Hamlet and King Lear—including his signature. As he finished the forgeries, Ireland presented them to his father, explaining that he'd met someone with a trunk of Shakespeare's documents, including original manuscripts, but could only obtain a few pages at a time.

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

An excerpt from William Henry Ireland's King Lear handiwork, included in detailed scrapbooks of his deception.

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

An excerpt from William Henry Ireland's King Lear handiwork, included in detailed scrapbooks of his deception.

Transfixed, Ireland's father published a book about his "original" Shakespeare relics titled Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments under the Hand and Seal of William Shakespeare. Emboldened by his success, Ireland penned a play titled Vortigem and Rowena, presenting it as a lost work by the Bard. The piece made its way to a performance at London's Drury Lane—but the skeptics closed in, with one leading Shakespeare scholar publishing an exhaustive takedown of the scam. In an unfortunate twist, the public accused Ireland's father of the forgeries.

Even when Ireland published his truthful accounts of the events, many critics refused to believe that he could have completed the forgeries alone. His father's reputation never fully recovered, while Ireland continued to write and publish books but never achieved any real degree of success. He was perpetually impoverished, even spending time in debtor's prison, until his death in 1835.

In another attempt to explain himself, Ireland created scrapbooks that documented his con trick. These volumes contain letters, examples of fabricated signatures, and other print ephemera all related to his Shakespeare forgeries. The UI houses five of these scrapbooks, gifted from the private collection of former English faculty member John Hubert Scott who taught at the UI in the early part of the 20th century. Fascinated with the story, he often traveled to England in search of historical documents and books tied to William Henry Ireland—a man with a fate worthy of Shakespearean tragedy.

Beatrix and Her Bunny

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

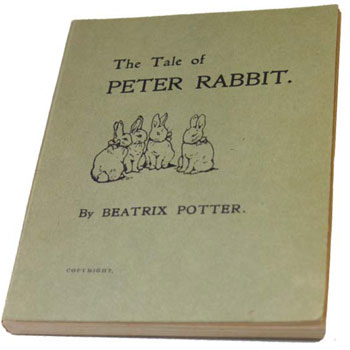

The Tale of Peter Rabbit is one of the most celebrated children's books of all time. The shenanigans of this naughty bunny in Mr. McGregor's garden in England's Lake District are so widely adored, it's astounding to comprehend that author Beatrix Potter struggled to find a publisher. But she did.

Undaunted, Potter took matters into her own hands. Upon finishing her story in 1900, and after repeated failures to find a publisher to produce her book, she paid a printer to make a couple hundred copies for friends and family. Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle even acquired one for his children. The UI owns one of these privately printed first editions gifted from the library of James M. and Christine K. Wallace—a small, light green book in near perfect condition that was once part of Potter's private collection. Known for collecting items that left a mark on the history of the genre, the Pennsylvania-based Wallaces donated some 240 children's book titles in the late 1970s, including rare editions of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, A Christmas Carol, and Winnie the Pooh.

By 1902, after seeing the privately printed version, British publishing house Frederick Warne agreed to distribute Potter's book if she would redo the illustrations in color. The rest is history. The book was a runaway hit, and the company issued multiple reprints. The Tale of Peter Rabbit has been translated into 36 languages and, with 45 million copies sold, it is one of literature's best-selling books.

While collectors consider first editions of the Frederick run great finds, the privately printed versions are far rarer. The UI's copy is valued at over $200,000. Says Prickman: "Peter Rabbit occupies a central place in the great tradition of literature that we continue to pass on to our children. To show people how it first appeared, and tell the story of its creation with a copy handled by Beatrix Potter herself, takes away the mystery of rare books and leaves us with a very real sense of the people and processes that make up our culture."

For the Love of Doggies

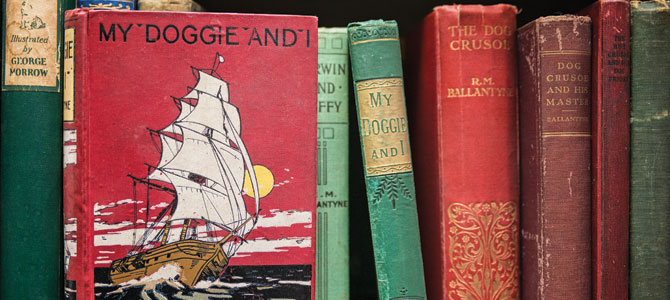

"I possess a doggie—not a dog, observe, but a doggie. My doggie is unquestionably the most charming and in every way delightful doggie that ever was born."

So begins the 1881 sentimental story My Doggie and I about the bond between a boy and his dog by R.M. Ballantyne, one of the 2,000 rare and antiquarian dog-related books in the collection of retired UI staff member Brian Harvey, 64BA, 66MS. Roughly half of the collection, with endearing titles such as Our Devoted Friend the Dog, The Story of Shep, and Kennel Secrets, currently occupies shelves in a holding area at the main library.

Spanning the 16th to the 19th centuries, the vast canine cache took shape in 1989 when Harvey adopted his own first doggie, an English sheepdog named Sredni Vashtar (named after a favorite short story by Saki). Starting out simply to educate himself about the breed, Harvey proceeded to read—and buy—a lot of books. From learning about the historical significance and development of certain breeds to gathering literary works featuring dogs, Harvey stumbled into the collecting business. Soon, he owned a small library.

Collecting gave Harvey the satisfying opportunity to fuse his passions for both dogs and books. Through his job as the UI's director of sponsored programs, Harvey often took time to poke around in old bookstores while traveling for work—and rarely failed to make a new discovery. He recalls, "I set out thinking it might be cool to own a small collection of dog books, not realizing how many are out there. I'd usually come out of a bookstore with at least one."

His collection includes some of the earliest breed and caretaking books on hounds, collies, and terriers—dogs owned primarily for working and hunting. He also owns early works that use dog stories as satirical commentary on society, politics, and government, as well as sentimental stories popularized during the 19th century, such as Dog Heroes of Many Lands. While Harvey keeps much of his collection in his Iowa City home, most of his Victorian and early 20th century books currently reside at Special Collections because they are the subject of a graduate student's dissertation study on the genre during this period.

Through his books, Harvey notes how literature responds to the evolution of history—in how dog characters reflect the popular breeds of the time or the way authors start to anthropomorphize and express a growing empathetic attitude toward animals. These later stories about the bond between humans and dogs appeal to Harvey most; these are the tales (tails?) that have stolen his heart over the years.

With their intelligence, loyalty, and unconditional love, dogs inspire the human imagination in ways that few other animals do. People adore dogs, Harvey says, and honor them with stories.

Sci-Fi Gold

Pete Balestrieri is on box 25 of 500 of the extensive Rusty Hevelin collection. To an aficionado of early American science fiction—the Golden Era of such literature—this prized collection is literally out-of-this world.

A processing librarian in Special Collections, Balestrieri, 12MA, faces the challenge of sorting, alphabetizing, and cataloguing thousands of science-fiction paperbacks, hardcovers, fanzines, convention materials, and pulp magazines collected by Hevelin from the 1930s onward.

A World War II veteran from Ohio, Hevelin was an active member of the earliest science-fiction communities, publishing his own fanzines and founding PulpCon—the first annual convention in the U.S. dedicated to pulp magazines (a name derived from the cheap wood pulp paper on which they were printed, although they often contained stories from many respected writers). After Hevelin's death in 2011, his extensive collection came to the UI by way of his Iowa connections, including a friendship with Iowa Writers' Workshop graduate Joe Haldeman, 75MFA, author of the Hugo award-winning sci-fi military novel The Forever War. A few years ago, Greg Prickman met both Haldeman and Hevelin at the ICON Iowa science fiction convention in Cedar Rapids, and promised that the UI would keep Hevelin's collection whole. Consequently, he won the bid to bring all the materials to Iowa City.

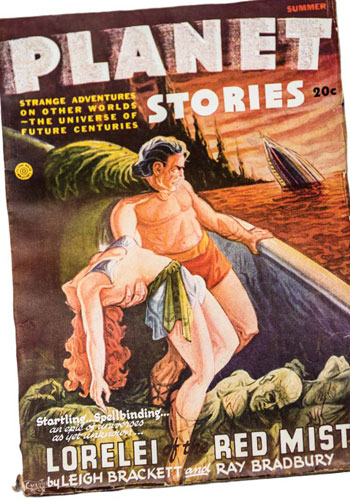

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

Sci-fi legend Ray Bradbury shot to fame through stories in pulp magazines like this one. Never forgetting where he got his start, Bradbury submitted other work to such publications—well after achieving fame.

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

Sci-fi legend Ray Bradbury shot to fame through stories in pulp magazines like this one. Never forgetting where he got his start, Bradbury submitted other work to such publications—well after achieving fame.

Throughout his life, Hevelin attended as many science-fiction conventions as he could and was regularly a featured guest of honor. In the process, he befriended some of the genre's biggest names, including Robert Bloch, author of Psycho, and writer Ray Bradbury, whose award-winning dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 firmly established sci-fi as a literary force of social and political relevance. Considered Bradbury's best work, the novel— which takes its title from the temperature at which paper erupts into flame—is set in a futuristic American society that burns books, along with any new or dissenting ideas.

Hevelin first met Bradbury, Bloch, and others in those early sci-fi clubs of the '30s and '40s, and they faithfully sent him copies of their work. Even after Bradbury's critical success, he continued to attend club meetings as both an author and fan. In fact, Hevelin's collection includes Bradbury's first appearance in commercial print in the pulp magazine Planet Stories. With fellow sci-fi author Leigh Brackett, Bradbury co-wrote "Lorelei of the Red Mist" about the adventures of a space thief on Venus.

"Sci-fi is the only literary genre so heavily influenced by its fans and where so many fans become producers," says Balestrieri, who enjoys opening each box to discover new and exceptional surprises, several of which he's sharing on a Special Collections Tumblr account so the public can watch as he unpacks.

Recently, he stumbled across a treasure in Hevelin's copy of Tolkien Journal Vol. III No. 1 (1967), in which fanzine publishers celebrated J.R.R. Tolkien's birthday by printing celebrities' greetings to the Lord of the Rings author. In its pages, Balestrieri found a submission from Mary Poppins author P.L. Travers, known as a formidable personality not likely to suffer fools. He chuckles at her dig: "Yes, I am an admirer of Tolkien's work—particularly of the Hobbit, which seems to me a perfect and complete lyric. I am not a member of the Tolkien cult, however—Frodo lives in spite, not because of, buttons and posters!"

Indeed, characters like Frodo, Mr. Spock, and the unforgettable monsters and time travelers from the Twilight Zone endure to the present day for the thought-provoking and philosophical ways they help divine meaning from the world—the same reasons bibliophiles love their books.

To view Pete Balestrieri's Tumblr showcasing his science-fiction finds, visit hevelincollection.tumblr.com.

For the Special Collections blog, check out http://blog.lib.uiowa.edu/speccoll.

Any comments about this article? Email uimagazine@foriowa.org.