Diane Oliver’s Unfinished Story

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

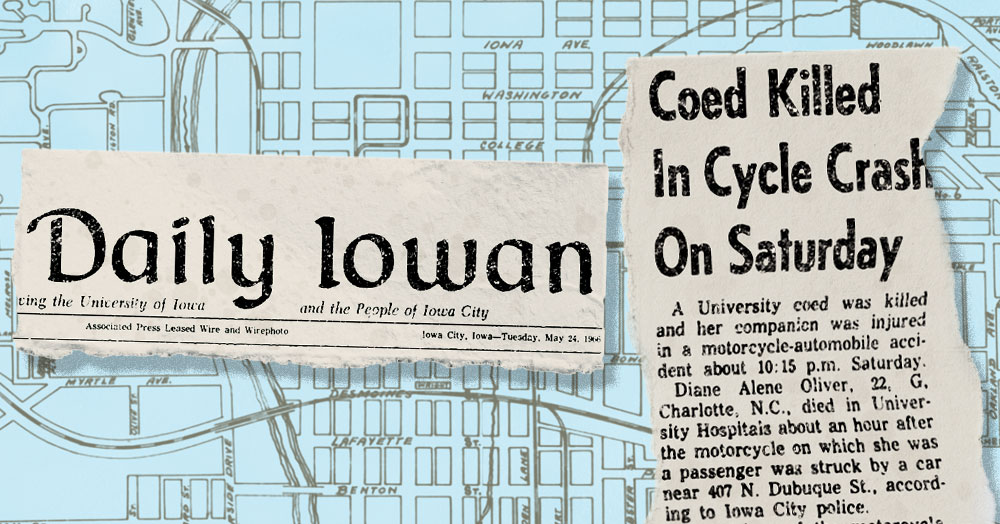

If someone were to map the life of Diane Oliver (66MFA), three street corners would be marked with pushpins. First, the corner of Mulberry Street and Washington Avenue in McCrorey Heights, the African American neighborhood where she came of age in then-segregated Charlotte, North Carolina. Next, the corner of Tate Street and Walker Avenue in Greensboro, North Carolina, where she and her college classmates braved picket lines during a boiling point of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. And last, the intersection of North Dubuque and East Davenport Streets in Iowa City, where—days before her graduation from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—she was thrown from a motorcycle and killed.

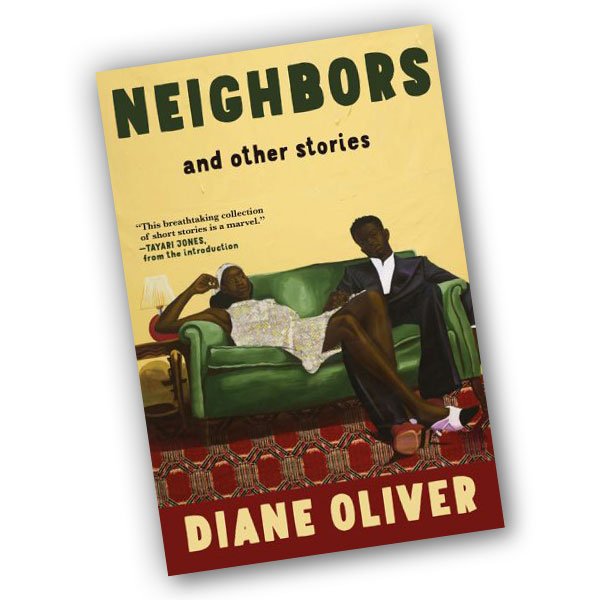

All the miles in between those markers, 22 remarkable years’ worth of material, are distilled into the writings she left behind, including six short stories that scholars have compared to the work of literary icons such as William Faulkner, Shirley Jackson, and Alice Walker. Oliver’s place in their ranks was little known until February, when Grove Atlantic in the U.S. and Faber & Faber in the United Kingdom released the first-ever collection of her published works. The book, Neighbors and Other Stories, is introduced by author Tayari Jones (94MA, An American Marriage) and blurbed by Iowa Writers’ Workshop assistant professor Jamel Brinkley (15MFA, A Lucky Man) and "Ursa Short Fiction" podcast co-host Dawnie Walton (18MFA, The Final Revival of Opal & Nev), among other celebrated writers.

A couple relaxing on a 1960s-era couch gazes up at the reader from the collection’s cover art, well-dressed and weary-eyed. They represent the people Oliver portrays in her stories: midcentury young Black Southerners who board crowded buses north, or shush their kids in waiting rooms, or toil in white families’ homes all day so they can come home at night to take care of their own.

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

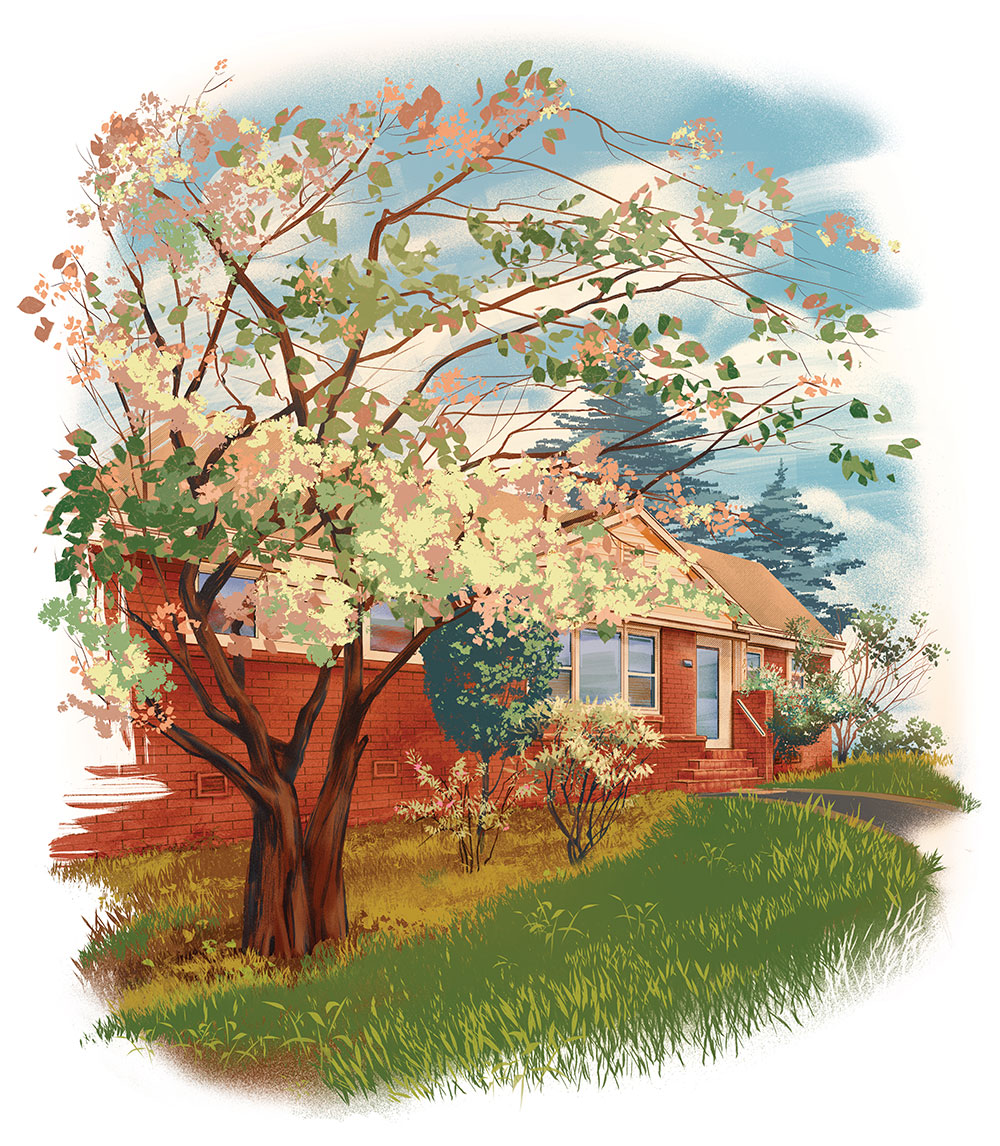

Mulberry Street and Washington Avenue, Charlotte, North Carolina

Oliver’s upbringing, however, was not identical to that of her poor and working-class protagonists. She was a member of the African American middle class—a relatively miniscule elite back then, especially in the South. Black middle-class families drew their social status less from wealth (they typically made much less than middle-class white families) or from zip code (they lived in segregated all-Black neighborhoods that were socioeconomically diverse) than from education.

Oliver hailed from a line of teachers, and her grandparents attended college. Her parents, who both had master’s degrees, owned a red-brick house on Washington Avenue in Charlotte, with a flowering tree in the front yard and a picture window through which passersby might glimpse her mother, Blanche, teaching piano and voice lessons. Oliver’s father, Bill, was a teacher who later became a school principal; Diane’s younger sister, Cheryl, who still lives in Charlotte, followed in his footsteps.

As Diane and Cheryl walked home from school, they would have greeted a procession of distinguished neighbors, including the Rev. J.A. DeLaine, who helped bring one of the lawsuits behind the landmark 1954 school desegregation ruling Brown v. Board of Education, and Rufus Patterson Perry (27MS, 39PhD), the president of nearby historically Black Johnson C. Smith University, Bill Oliver’s alma mater.

A relentless reader, Diane perhaps would have carried a stack of books under her arm, ready to show them off to her grandmother—who, Cheryl remembers, fostered her and Diane’s love of words, introducing them to Black poets such as Paul Laurence Dunbar and James Weldon Johnson. “We learned to recite it; some of it I can recite now,” says Cheryl, who is now 76. “It’s still in my head from trips we took as kids in the car. That was our entertainment—and telling stories.” By 12 or 13, Diane aspired to become a writer herself.

Photos show she had movie star looks, a Mona Lisa smile, and a trim fashion sense. “She was beautiful,” says Cheryl, “but she didn’t act like she was.” Soft-spoken Diane instead seemed to prefer the world of fictional characters to her own. “When my parents would call for dinner, she ignored it,” Cheryl recalls. “And they would say, ‘Oh, she’s with her book people.’”

Bookishness didn’t preclude her wry wit, however, which attracted a sizable social circle. Diane was friendly, for example, with Dorothy Counts, who left their segregated high school in 1957 to become the first Black student at Charlotte’s all-white Harding High School. The four harrowing days Counts attended Harding generated an international firestorm and produced one of the most famous photos of the 1960s: Counts walking to school in her checkered dress as an enormous crowd of white classmates and onlookers jeered, laughed, and spat at her.

“She was beautiful, but she didn’t act like she was.” —Cheryl, Diane Oliver's sister

Her friend’s experience with integration shook Diane Oliver’s foundations. Her entire community could speak of nothing else. “You overheard teachers talking,” Oliver’s classmate Madge Hopkins told a Southern Oral History Program interviewer in 2000. “Everybody knew about it.”

The theme of failed integration wove its way into Oliver’s work—most particularly “Neighbors,” the title story of her new collection, which shadows the family of a boy the evening before he becomes the first Black student at an all-white school. Many readers have speculated that the piece is based directly on the Counts ordeal.

Much as Oliver thrived in her own mostly Black high school—winning the annual countrywide Betty Crocker Homemakers of Tomorrow writing contest, working on the school newspaper and yearbook, and being dubbed “Miss Journalism”—she must have sensed she was soon to turn that next important corner, en route to the front line of the Civil Rights Movement. Her childhood friend Linner Ward turned with her: They both accepted admissions offers from Woman’s College (now the University of North Carolina, Greensboro) to help integrate the predominantly white, all-female institution.

The semester before they enrolled in 1960, both young women watched news reports of Black students in Greensboro refusing to budge from a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter, returning every day for months until African American customers could be served there too. Those nonviolent protests became known as sit-ins, and the sit-in movement erupted across the country that year. But the furious, counterprotesting white faces on TV did not inspire confidence in Ward or Oliver. How would they manage when surrounded by such hostility?

According to Ward, in an interview for the UNCG Libraries’ Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, she and Oliver made a pact: “When we went to this college, we weren’t sure what to expect, so we said we’re going to room with each other the first year. And then, after that, we would know people well enough to be able to venture out.”

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

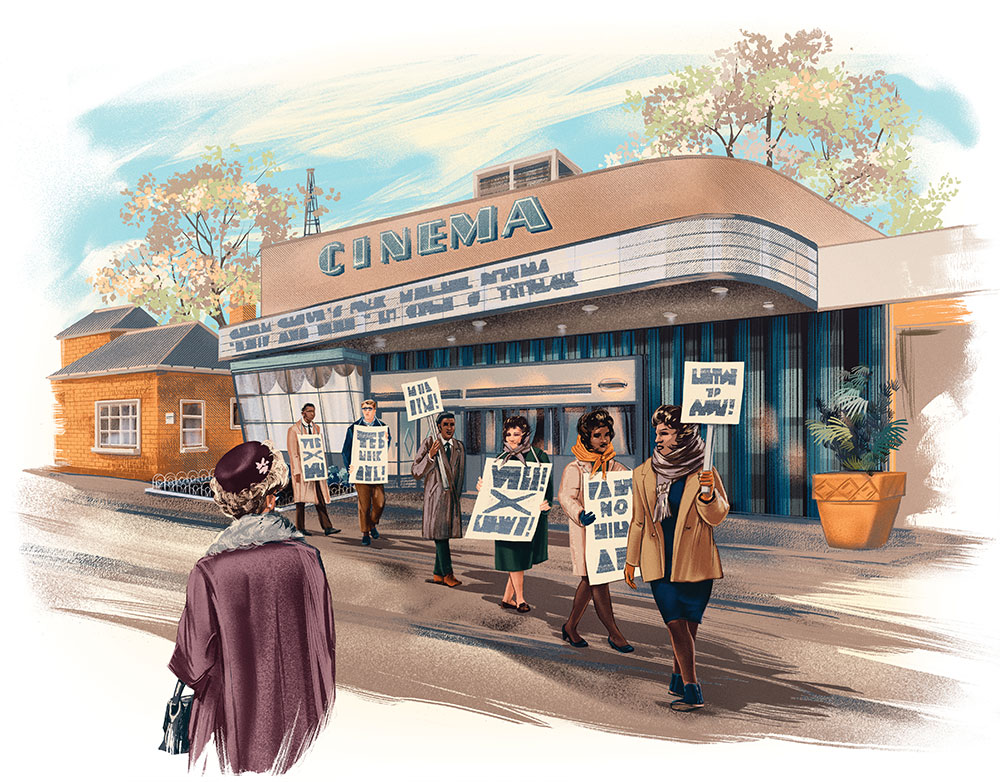

Tate Street and Walker Avenue, Greensboro, North Carolina

The two were among a handful of Black students in Woman’s College’s class of 1964—all placed in the same hall, separate from the other students, so white pupils would not have to share bathrooms or kitchens with them. Ward was “a little disappointed” at the lack of integration, but the group seemed determined to make the most of their surroundings: They bonded with each other and reveled in the extra dormitory space. The young women also socialized with the city’s other African American students—including two of the original Greensboro Four whose sit-ins inspired bus integration efforts, voter registration campaigns, and the March on Washington.

Despite culture shock, a heavy workload, and late nights of bid whist and pinochle with her dormmates, Diane Oliver wasted nary a second pursuing her journalistic ambitions. She took grammar, literature, and French, and became the only African American staff member of the school newspaper, The Carolinian. One dormmate described her as “kind of an introvert,” but another remembered that Oliver “did not segregate herself. Some of us went out of our way to socialize across races and some of us didn’t.” Oliver was one of the people who did.

Cheryl Oliver marvels in retrospect at the number of white friends her sister introduced her to when she visited Diane on campus. Among the closest was Debbie Kahn, one of two Jewish women who eventually moved into the segregated hall. In an interview for the UNCG archive, Kahn (now Debbie Kahn Rubin) explained the significance of the connection: “I didn’t have any interactions with African Americans [growing up] other than servants or people in stores and that sort of thing.” Yet, with Oliver and the other Black students, “we pranced around in our pajamas ... studied together ... for me, it was very comfortable.”

“We caused stares because no young white girls greeted and hugged and got in the car with young Black girls in 1961.” —Debbie Rubin, A COLLEGE CLASSMATE OF DIANE OLIVER

One memory, though, hit a wrong note in Kahn’s mind: She invited Oliver to see a movie at the corner of Tate Street and Walker Avenue. “[Diane] said, ‘Well, you know I won’t be able to sit with you, and I can’t go.’ I think she had to enter another entrance and sit in the balcony, and that was the first time I realized that there were limitations.”

The same summer as the Freedom Rides, where white and Black activists sat beside each other on buses headed South to protest segregation in public transportation, Bill and Blanche Oliver permitted Diane to accept Kahn’s invitation to visit her home in South Carolina. “I remember at the Greyhound station when I picked her up,” Kahn Rubin told her UNCG interviewer. “We caused stares because no young white girls greeted and hugged and got in the car with young Black girls in 1961.”

Oliver met the Kahn family, Debbie’s white childhood friends, and the Black woman who cooked for the family. When Oliver returned Kahn’s invitation, however, Kahn’s father wouldn’t let his daughter visit the Oliver home. It was too dangerous, he warned, for Debbie and for the Oliver family.

Around this time, Oliver began crafting short stories. Any number of happenings could have elicited them: the Cuban Missile Crisis; her writing classes with novelist Peter Taylor and poet Randall Jarrell; the continuing sit-ins, which morphed into student boycotts of restaurants; and picket lines on the same street corner where she could not see a movie with Kahn. Though not published until a few years later, her story “The Closet on the Top Floor” could have occurred to her then—its central character is a Black student whose alienation from the white women’s college she is integrating causes her to disappear.

Oliver did much the opposite. She was promoted to managing editor of The Carolinian and became a front-and-center supporter of the protests on Tate Street, listing herself on a campus flyer as a contact for classmates who wanted to picket. Although the chancellor warned that any students arrested would face expulsion, many of Diane’s Black and white friends picked up signs that spring of 1963, just a few months before Martin Luther King Jr. delivered “I Have a Dream” in the nation’s capital. As Linner Ward recollected, by the following fall—their final year in college—the two stores and the cinema on the corner of Tate Street had fully integrated.

Objectively, Oliver’s senior year was filled with laurels. An essay about the protests won her a summer guest editorship in New York at Mademoiselle, the era’s leading U.S. magazine for young women. She was also selected to participate in an Experiment in International Living program later that year, where she would study French and live with a host family in Switzerland, and she landed a full graduate scholarship to the University of Iowa for the 1965–66 school year.

An article in The Carolinian just before she graduated from UNCG interviewed Oliver in her dorm room in front of her typewriter. The reporter asked what she was working on, and Oliver said it was a piece she hoped to publish about a young boy who attends an integrated school.

Printed in The Sewanee Review two years later, “Neighbors” has become her most anthologized work; it also received third prize in the 1967 O. Henry Awards. In a 2022 Bitter Southerner article about Oliver, critic and essayist Michael A. Gonzales observed that within “Neighbors,” “there is a sense of social realism that is as straightforward as an essay on the regular folks behind the movement.” To her college newspaper, Oliver deemed it simply “a quiet little story—I just can’t seem to write any other way.”

The record doesn’t offer many details about Oliver in New York or in Europe. In broad strokes, she completed her guest press editorship with Mademoiselle, working on the August 1964 “College Issue” with young fabric editor and future fashion designer Betsey Johnson.

Oliver likely traveled to England with fellow guest editors to tour Oxford University and William Shakespeare’s birthplace, then returned to the Big Apple for a look at New York’s publishing houses. That fall, she crossed the Atlantic again to spend eight weeks living with a Swiss family, immersing herself in French, and no doubt working on a new story, “Key to the City,” which became her first-ever published fiction—in the Red Clay Reader the following fall, just as she enrolled in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

IMAGE: W.FLEMMING ILLUSTRATION

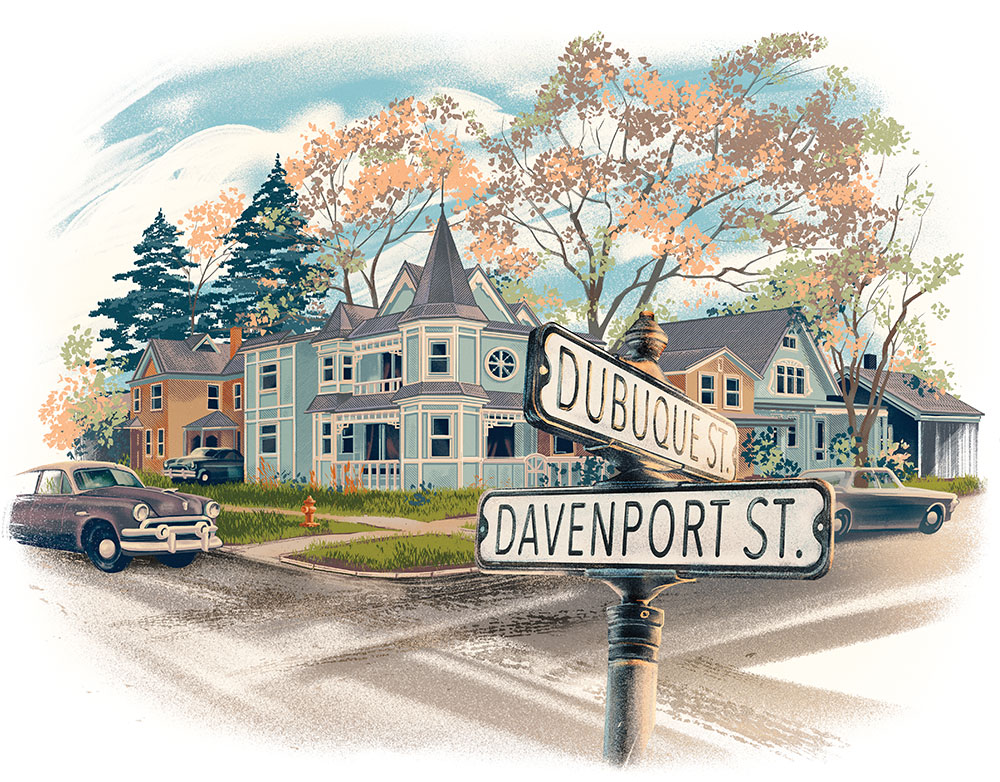

North Dubuque Street and East Davenport Street, Iowa City

Oliver must have passed that fateful crossroads frequently without pausing. North Dubuque and East Davenport Streets met on the way from her Iowa City apartment to Black’s Gaslight Village, a section of Brown Street where many of her Workshop friends lived. Fiction classmate Suzanne McConnell (67MFA), in an essay for the program’s 50th anniversary, reminisced about her and Oliver’s cohort from 20 years back: A contingent largely of white men, they held their classes in Quonset huts. They were taught by fiction writers Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Yates, Vance Bourjaily, and Nelson Algren. Oliver may well have been the only nonwhite, let alone African American, writer of the group—and though she meshed well with everyone, according to McConnell, “Diane always seemed so cautious and careful, but I suppose, considering what she was surrounded by, she had to be that way.”

The Daily Iowan that year told a slightly different story. Oliver, it reported, was a local civil rights advocate and the publicity chairman for the Committee to Defend Iowa Students. That school year, the committee had unofficial overlap with the university’s chapter of the activist organization Students for a Democratic Society and publicly supported UI students who burned their draft cards to protest the Vietnam War.

In the span of two semesters, Oliver also completed most of her oeuvre. Negro Digest published two of her short stories, “Health Service” and “Traffic Jam,” in fall 1965 and summer 1966. A third—the horror-inflected “Mint Juleps Not Served Here”—was anthologized a year later in Southern Writing in the Sixties.

Author and Iowa Writers’ Workshop alum Dawnie Walton’s two favorite short stories of Oliver’s (“Health Service” and “Traffic Jam”) involve a single mother of five children. Walton marvels that “these stories were written so long ago, but at the same time, they’re actually very contemporary, in the sense that they are trying to make sense of an era that the author is living through.”

“When you’re still trying to develop your voice, it’s difficult when you have all these other voices coming in. It can be intimidating.” —Dawnie Walton

Walton finds Oliver’s productivity unusual; her own experience at the Workshop in the late 2010s included several other Black women who offered each other moral and literary reinforcement. Between Oliver’s youth, at 22, and the homogeneity of her 1960s cohort, Walton “just can’t imagine producing work at that level under those conditions. … I’m assuming she was getting all kinds of crazy feedback—insulting, probably, at times—simply because there was nobody there who could be a support in that way.

“I think some younger people who go into the Workshop, they tend to struggle a little bit,” she adds. “And not even because they’re the only person of their background or situation, but because when you’re still trying to develop your voice, it’s difficult when you have all these other voices coming in. It can be intimidating.”

By 1966, however, Oliver’s voice had become pronounced enough to attract Johnson Publishing Company—the force behind Negro Digest, Ebony magazine, and Jet. The latter publication offered her an editorial position starting in June after her graduation from the Workshop. She would relocate to Chicago, now the hub of the Civil Rights Movement in the North, armed with her MFA and her social conscience and the job in publishing she had dreamed about since those days of reading with her grandmother.

But, first, a pig roast was in order—a Workshop celebration at Black’s Gaslight Village to mark a cohort’s impending graduation. Suzanne McConnell, who was present, wrote in her essay that the beer was flowing and the conversation lively. Several undergraduate seniors sat around the table with her and Oliver and the other writers. One of them, a young fiction student, was a stranger to Oliver. Around 10 p.m., it had become dark—too dark for Oliver to think of walking home. She needed a ride, and the fiction student offered. It would be fun: He had a motorcycle, and Oliver had never been on one before.

Perhaps the fiction student didn’t have an extra helmet, or maybe he wasn’t wearing one either. The article in The Daily Iowan on May 24, 1966, didn’t specify. What it told was that Oliver climbed on the motorcycle behind him, and they roared off toward her apartment. When they reached North Dubuque and East Davenport, a Volkswagen emerging from an alley didn’t yield the right of way. The collision flung Oliver from the moving bike. She and her fellow passenger were taken to the university’s hospital, where he was pronounced “in good condition.” Less than an hour later, Diane Oliver died. She was 22 years old.

The University of Iowa conferred Oliver’s MFA posthumously. Her family arrived to escort her body back to Charlotte. Her Workshop friends wept or punched holes through walls. Her college friends attended her funeral. One of them told a UNCG interviewer that what happened to Oliver was “one of the major traumas of my early adult life.” Another, speaking 45 years after the fact, remarked, “I think of her often.”

The Road Ahead

Much more will be written, of course, about Diane Oliver’s published work—its richness, its incisiveness, its contemporary resonance. Her stories have remained timely during the past half century, quietly anthologized in Black Voices: An Anthology of Afro-American Literature (1970), adapted into a film for the PBS trilogy Tales of the Unknown South (1984), and saluted by writers Dawnie Walton and Deesha Philyaw in a two-part episode of the "Ursa Short Fiction" podcast. In his 2022 article, Michael A. Gonzales compared her alternately “gothic” and “naturalistic” narratives to that of Get Out filmmaker Jordan Peele.

The U.K.-based literary agent Elise Dillsworth saw Gonzales’ tribute and became intrigued. She dusted off out-of-print compendiums, searching for Oliver’s stories, and found “Neighbors.” “I was astounded by its acute observation of the personal and political dynamics of race,” Dillsworth recalls. “I couldn’t quite believe that I had never come across Diane Oliver.”

“[Oliver is a] missing figure in the canon of 20th-century African American literature.” —Neighbors synopsis

Further sleuthing, with help from McConnell and Iowa Writers’ Workshop librarian Leah Agne, linked her with Oliver’s niece, Kim, on Facebook. Kim alerted Cheryl Oliver, who found herself well prepared for this moment: “My mother had kept all [Diane’s] stories in a box with folders and labels,” she says. “So when Elise contacted my daughter on Facebook, all we had to do was pull the box.”

Soon, the three women were Zooming about publishing a compilation of Diane’s work. At first, Cheryl was cautious: “I asked her how much would everything cost, and she said, ‘It wouldn’t cost you anything. In fact, you would make money.’”

Indeed, Dillsworth, who now represents Diane Oliver’s literary estate, worked with the family to secure two renowned publishers, Grove Atlantic and Faber & Faber. The book will also be published in France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden. Its synopsis hails Oliver as a “missing figure in the canon of 20th-century African American literature.”

Another list on which her name belongs, a longer though perhaps less lauded one, is of young Black women in the 1960s who struggled, sometimes in vain, to better all the world’s street corners for themselves and their neighbors—to spur the Civil Rights Movement forward. The routes Diane Oliver traveled during her too-brief life, and all six stories in her long-overdue collection, reflect an extraordinary attunement to the inner lives of the people for whom, and by whom, that movement was forged.

PHOTO: COURTESY CASSANDRA JENSEN

PHOTO: COURTESY CASSANDRA JENSEN

Cassandra Jensen (20MFA) is a graduate of the UI’s Nonfiction Writing Program who writes about 20th-century African American history. A 2017–18 Iowa Arts Fellow and a former nonfiction editor at The Iowa Review, she currently works as an associate editor for the Council on Foreign Relations.