Horror Author and Iowa Alum Daniel Kraus Cooks Up Burger Nightmare

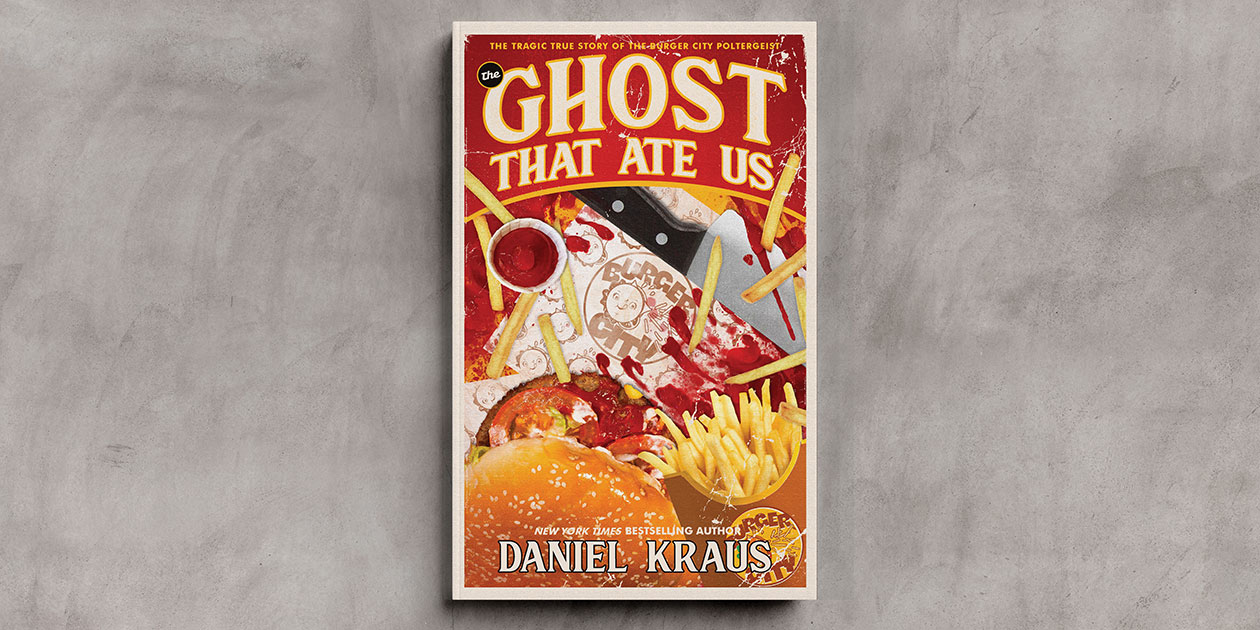

The Ghost That Ate Us by Daniel Kraus (97BA), Raw Dog Screaming Press, 302 pp.

The Ghost That Ate Us by Daniel Kraus (97BA), Raw Dog Screaming Press, 302 pp.

Growing up in Fairfield, Iowa, Daniel Kraus would stay up late to watch horror movies like Night of the Living Dead and old episodes of The Twilight Zone with his mom. But what would have been nightmare fuel for most 5-year-olds only fed Kraus’ insatiable imagination. “I was able to make a positive association with horror,” says Kraus (97BA). “She was laughing and having fun. It made horror a safe space I shared with her.”

photo courtesy Daniel Kraus

Daniel Kraus

photo courtesy Daniel Kraus

Daniel Kraus

He channeled his love for scary movies into monster drawings and short stories, which by high school became novel-length horror tales. Today, Kraus is a filmmaker-turned-author who is known for his horror and science fiction novels and collaborations with other masters of the macabre. Most notably, he partnered with Guillermo del Toro to create the 2017 Academy Award-winning film The Shape of Water. He also co-authored its novelization with del Toro. And in 2020, Kraus completed and published horror pioneer George A. Romero’s unfinished, epic zombie novel, The Living Dead.

Kraus recently spoke to Iowa Magazine from his home in Chicago about his career, including his 2010 documentary Professor, which followed beloved University of Iowa religious studies professor Jay Holstein. The UI communication studies graduate and bestselling author also discussed his latest novel, The Ghost That Ate Us: The Tragic True Story of the Burger City Poltergeist, which releases July 12. Described as a “fictionalized true-crime story,” the book unravels the mysterious circumstances behind six gruesome deaths at a fast-food restaurant off Interstate 80 in rural Iowa.

What did Professor Holstein’s teaching mean to you as a student, and what was it like to make a documentary about him?

As time passes, there are certain things you remember about college and certain things that fade away. I don’t remember many teachers, but you never forget a teacher like Jay Holstein. I believe his class, Judeo-Christian Tradition, was the very first class I attended my freshman year. Then Quest for Human Destiny was the very last class I attended my senior year. I didn’t take any of his classes in between, but that bookended my time at Iowa. It was fantastic to have that feeling of returning to this person that, even then, had started to influence my thinking. One of my major regrets was that I only took two classes from him.

Coming back to do the documentary many years later did give me the chance to dip into some of his other classes without having to take the tests and be graded. The couple weeks I spent with Holstein on campus were, honestly, a couple of the happiest of my life.

What was it about monster stories and horror fiction that spoke to you as a storyteller?

There are people who react to getting scared in their life by running away from whatever it is. And that makes sense. But then there are people who prod at what scares them, to try to find out why it scares them. I was that kid who, if I was scared by a monster under my bed, I’d go beneath the bed at night. I’d do things I knew would scare me, because I almost couldn’t stop daring myself to do it. To this day, I’m most fascinated by the stuff I can’t handle, the material that is difficult for me emotionally. If you’ve got issues, and we all do, it’s an endless well from which to pull from because it feels so visceral and immediate.

In The Ghost That Ate Us, you use a true-crime format to tell a fictionalized story. Is this a new approach for you?

I don’t know how I came up with it, but I started fiddling with the idea of approaching a novel in a nonfiction style, adding a sort of realism to it in the same way a found-footage horror film has that patina of realism added to it because of its format. So, I thought, if I could have photos and footnotes and the kind of specifics you’re used to seeing in nonfiction, it might have the same effect. It might lend a veracity to the proceedings that get under your skin in a real way. You might think that maybe this did happen, and with all the funny and quirky news stories that fly at us in social media, maybe we missed this story about a poltergeist in an Iowa fast-food joint.

A lot of your stories take place in Iowa. Why is it a setting you revisit often?

When you spend your whole life in Iowa, I don’t think you realize how interesting it is. And this is the case wherever you live. Then when you go out into the wider world, you realize that you’re actually from a really unique place. For people in the city, the idea of these small towns, particularly in the pre-internet days, where you are really geographically and artistically isolated, is pretty fascinating. The fact that gas stations have live bait machines, or your dad is in the garage cutting up a deer, those things are almost fantastical to city folk. But I also felt a sort of darkness, not in Iowa specifically, but in the Midwest and small towns. I always had the sense that there was something creepy about small towns because of the isolation. Wide open spaces, paradoxically, can be claustrophobic. They can be a kind of prison, really.

You’ve worked with a lot of big names over the years. What was it like collaborating with del Toro?

The Shape of Water began as an idea I had when I was a kid, and so did my book Scowler. Both of those ideas knocked around in my head for decades before I found the right outlet and they allowed themselves to be assembled into story shape. From Guillermo, the main thing I learned was to love my characters a little more. My books preceding Shape of Water were more cynical, and he’s much more of an optimist than I am. So I gave it a try, and I found it did suit me a bit. There was room for happiness and heart and humor in the way I looked at life, and I could still get away with my dark view on things, and in fact it would amplify it.

How meaningful was it to be asked to finish writing Romero’s The Living Dead novel?

Rod Serling and George Romero were the first artists that affected me as a kid. I think Romero’s Night of the Living Dead was the first piece of art that made me think about the authorship of art. It made me think about its creation and who was the sort of person who made this. As I watched more of his films, I became a student of his work.

I wouldn’t exist as an artist without George Romero, so to be asked to finish off his last, great unfinished work was mind-blowing to me. The idea that I could complete a cycle that was really my own origin story was fantastical and the greatest honor of my career.