The Seven Ages of James V. Hatch

"One man in his time plays many parts," muses Jaques in Shakespeare’s As You Like It, and University of Iowa theatre arts graduate James V. Hatch (55MA, 58PhD)—a nationally known playwright, teacher, archivist, activist, filmmaker, and historian—was no exception. Admirers will remember Hatch’s puckish smiles and neckerchiefs, his tireless curiosity, and the $20 bills he’d slip to younger artists who were down on their luck.

Hatch mastered the craft of listening, and throughout his 70-year career persuaded more than 1,500 influential artists—most of them African American—to reminisce, perform, and tell their secrets for posterity. He and his wife, Camille Billops, turned their home into a recording studio, inviting Black theater legends and other creatives to interview one another.

In the Hatch living room, Black Arts Movement visionary Amiri Baraka discussed his influences with students at his feet; comedian Dewey "Pigmeat" Markham recalled how Sammy Davis Jr. took credit for his funniest sketch; and New York’s legendary Cotton Club dancers donned their tutus for one last show. Hatch captured all of this, and plenty more that would otherwise have been lost to history, to create a one-of-a-kind archive. He died in February 2020, just months before Iowa’s theatre arts centennial.

Back in 2004, after co-authoring A History of African American Theatre with historian Errol Hill, Hatch delivered an address at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. He used Shakespeare’s Seven Ages of Man monologue to frame the story of his life, tackling a question he’d fielded often during his career: How did a white boy from small-town Iowa become a pioneer in the world of Black theater?

Age I - THE INFANT

Hatch began his speech the same way the Bard had—with childhood. "Born the son of a country schoolteacher and a railroad boilermaker on the Great Western Railroad," he wrote, "I began my mewling and puking in October 1928, just in time to welcome the Great Depression." The full address, titled (with Hatch’s trademark irony) "African American Theatre: The White Man’s Journey," can be found on the Kennedy Center website, and records of Hatch’s Depression-era childhood survive in the National Archives.

During the 1930s, he and his parents lived in a neighborhood full of wage-working white railway families in Oelwein, Iowa’s Hub City. At the Kennedy Center, he reminisced about days as a milk delivery boy driving a wagon through town, as well as his two-mile walk each day to the schoolroom where he first encountered a Black person: Jim from the pages of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Age II - THE SCHOOLBOY

As a high school student during World War II, Hatch continued to read his way into a broader worldview. Too young for the draft at 16, he enrolled at Iowa State Teachers College (now the University of Northern Iowa) and found, as he told fellow theater scholar Kathy A. Perkins, that the English teachers were the most interesting.

After graduation, he married classmate Evelyn Marcussen and moved to Monticello, Iowa, where he, too, became an English teacher. He also discovered his passion for the stage. Tasked with overseeing the Monticello High School senior play, Hatch sought directing tips at the UI, where he joined summer theater productions courtesy of the Department of Speech and Dramatic Art. As the 1950s progressed, his life took on two tracks: one as a teacher, husband, and father; the other as a talented playwright with an increasing distaste for conformity.

"You were on time. You did what they said. You did it like they said to do it." —Jim Hatch

By 1954, Hatch had enrolled at the UI as a graduate student under the tutelage of E.C. Mabie, William Reardon, and theater history trailblazer Oscar Brockett. "All of them were excellent teachers, and demanding—you know, no-nonsense," he told Perkins in a 2009 oral history. "You were on time. You did what they said. You did it like they said to do it."

Among his fellow students were late theatre arts professor emeritus David L. Thayer (55MA, 60PhD), director and Drama Review editor Richard Schechner (58MA), and the first two Black friends Hatch ever had: playwright Ted Shine (58MA) and actor J.P. Cochran (58PhD). Hatch admired Cochran’s unforgettable stage presence and Shine’s luminous imagination. He liked to reminisce about Epitaph for a Bluebird (1958), starring Cochran and directed by Brockett on the UI Main Stage, a play Shine had written for an all-Black cast.

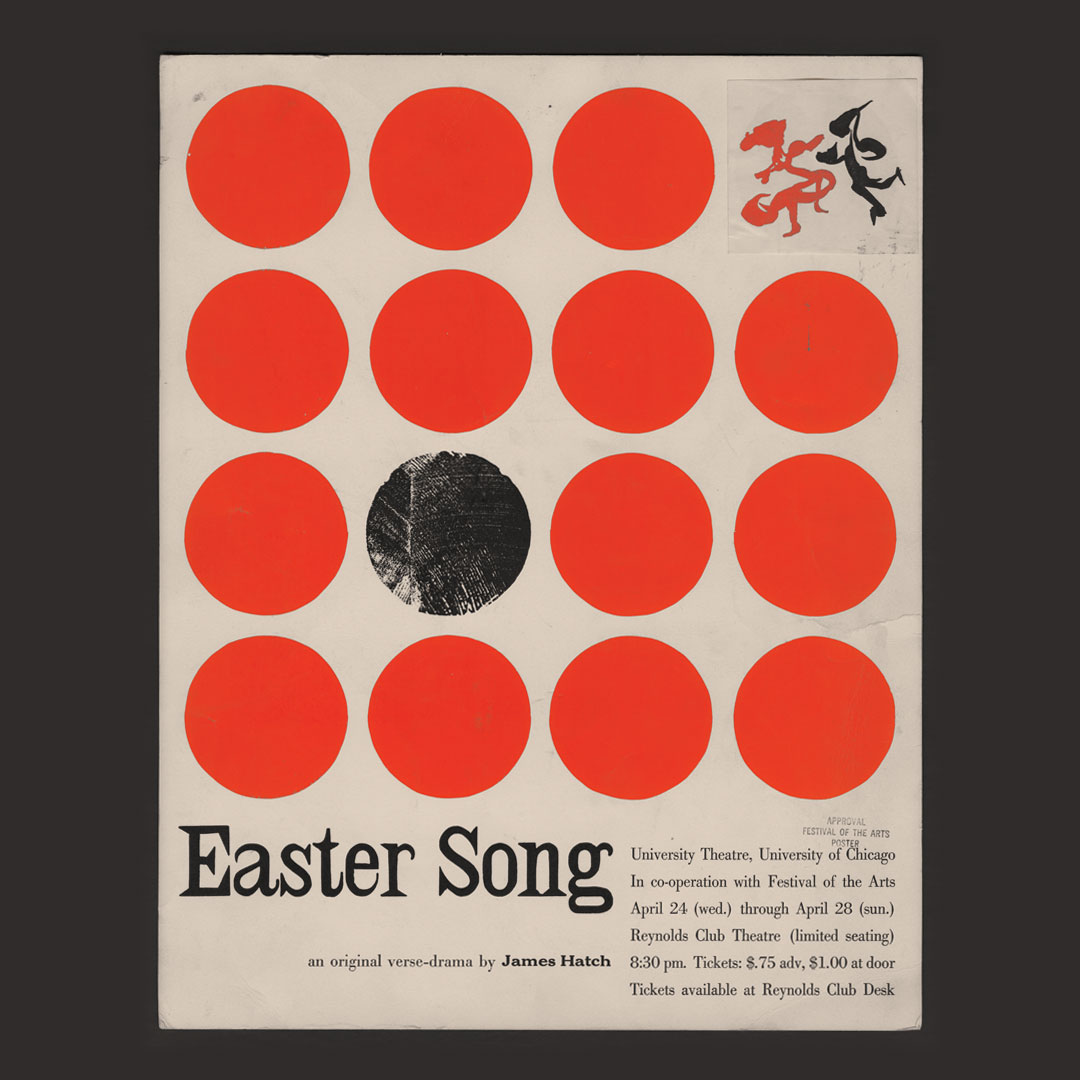

A poster from the University of Chicago production of Easter Song, one of Jim Hatch’s award-winning plays.

A poster from the University of Chicago production of Easter Song, one of Jim Hatch’s award-winning plays.

At the time, the UI had few students of color and even fewer Black actors—so Brockett and Shine took to the campus walkways. "They’d see a Black student, and they would stop him or her and say, ‘Would you like to be in a play?’ And that way they got a whole cast," said Hatch.

The play was a success—as were Hatch’s scripts. Easter Song, in particular, his 1956 drama in verse, won two awards and was later produced at the University of Chicago.

Around this time, the 28-year-old Hatch abandoned his high school teaching career to become a full-time PhD student in the UI’s innovative drama department.

Age III - THE LOVER

Two thousand miles west, another young parent and teacher with creative aspirations worked toward her degree. Los Angeles native Camille Billops was known for her iconoclastic fashion sense, her flair for ceramics, and the cutting remarks she stage-whispered to make friends laugh.

A single mother politicized by the era’s Civil Rights Movement, Billops longed to escape her nine-to-five and live freely as an artist. She also had a lovely voice, and her stepsister urged her to audition for a musical at UCLA. Billops liked the play and its rakish, bearded writer, who had just moved to California from the Iowa prairie. “I had never met anyone like Jim,” Billops told Emory University archivists in a 2019 interview. “I suggested that he come see my ceramics. And he did. And the rest is history.”

"I suggested that he come see my ceramics. And he did. And the rest is history." —Camille Billops

Jim Hatch, too, had been stirred by the turbulent times. The 1957 Little Rock Crisis, where Arkansas’ governor barred Black teenagers from integrating a public high school, horrified the teacher in him, while the sit-ins by college students against North Carolina’s segregated lunch counters galvanized him and his classmates.

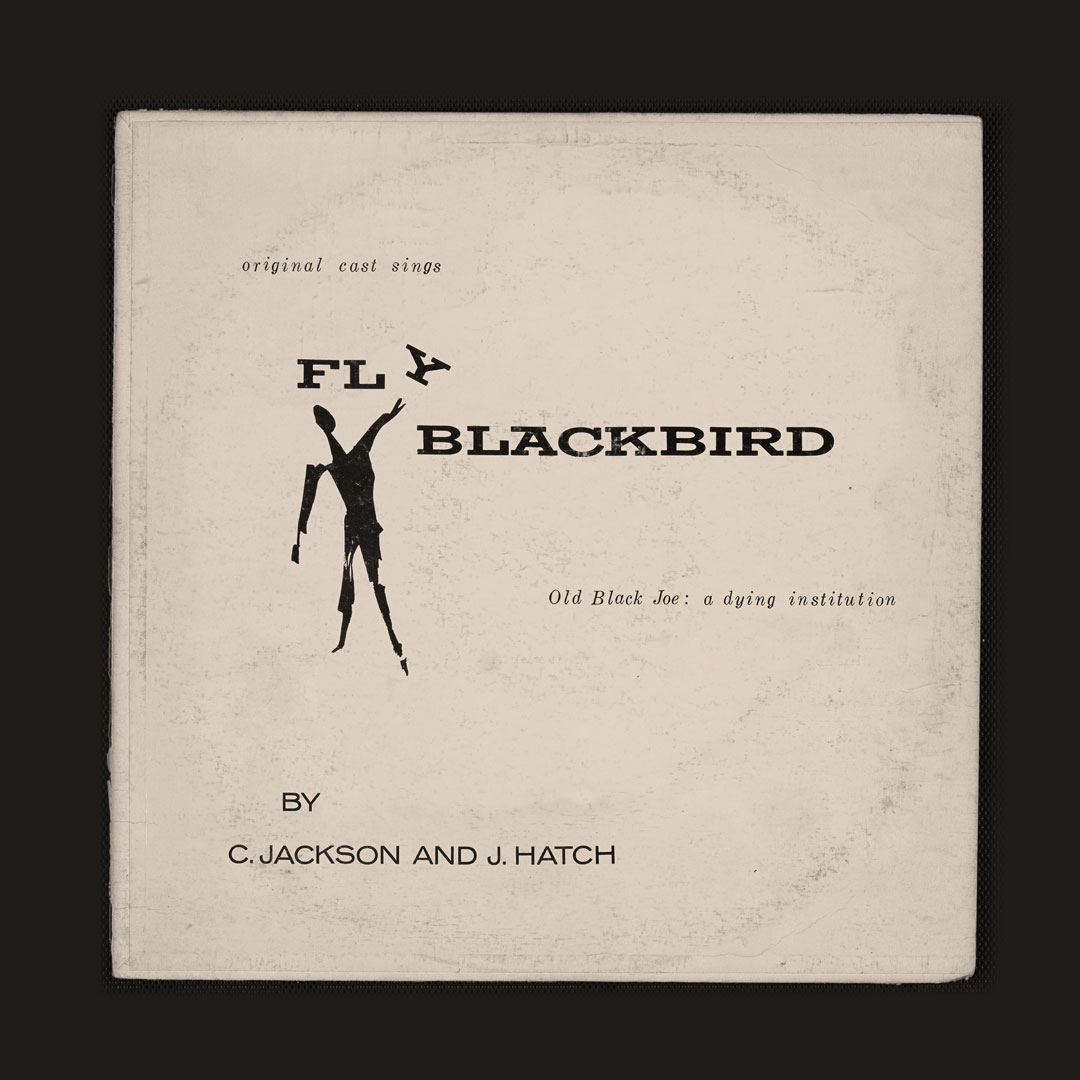

Playwrights Jim Hatch and C. Bernard Jackson collaborated on Fly, Blackbird, a musical about the Freedom Riders that won a 1962 Obie Award for Best Musical.

Playwrights Jim Hatch and C. Bernard Jackson collaborated on Fly, Blackbird, a musical about the Freedom Riders that won a 1962 Obie Award for Best Musical.

After earning a doctorate from the UI, Hatch moved his family to California, where he won a playwriting residency at Idyllwild and began teaching at UCLA. There he made a particularly influential friend, Black playwright and musician C. Bernard Jackson, whose immersion in Black culture and dedication to racial justice inspired Hatch’s own. “Once I had crossed that threshold of perception,” he wrote in his Kennedy Center speech, “I could not ever quite return to being a white liberal.”

The two co-produced the civil rights-themed Fly, Blackbird, which played at UCLA and then the city’s Metropolitan Theater. Its original stars included future Tony-winner Micki Grant and pre-Star Trek George Takei; a young Francis Ford Coppola provided carpentry skills and lighting design. Most memorable among the cast, at least for Hatch, was Billops, whose singing skills impressed him. It was the start of a love affair that marked the end of Hatch’s first marriage, and that lasted until Billops’ death in June 2019.

Age IV - THE SOLDIER

Though Hatch never served in the military, he did represent his country abroad. Not long after Fly, Blackbird was mounted in New York—where it earned the 1961 Obie (Off-Broadway Theater) Award for Best Musical—he received a Fulbright to teach for a year at Cairo’s High Cinema Institute. Leaving U.S. soil spurred Hatch to make dramatic life changes: He resigned his post at UCLA, and he and his wife, Evelyn, got divorced.

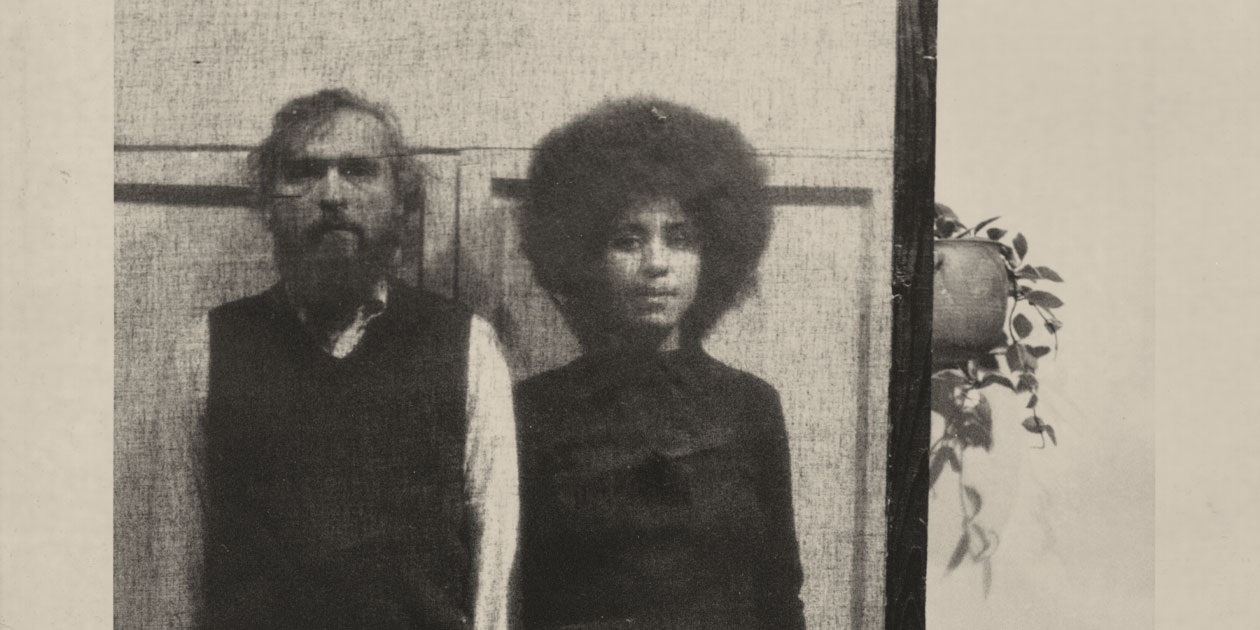

Camille Billops with Jim Hatch, who appears to be spoofing Grant Wood’s American Gothic in Sri Lanka.

Camille Billops with Jim Hatch, who appears to be spoofing Grant Wood’s American Gothic in Sri Lanka.

Egypt in the 1960s was a hub of the Pan-African Movement, an empowerment of African-descended people worldwide that also drew U.S. civil rights leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Malcolm X to the continent. Hatch found this new environment to be perhaps the most invigorating of his life. He kept journals during his years abroad and recollected fondly in his Kennedy speech that “I invited Camille to follow me to Cairo, where we lived in sin.” The couple befriended, among others, U.S. expatriate Maya Angelou. Cairo wasn’t their only destination: They traveled to China, Germany, Malaysia, India, and Sri Lanka, teaching art and directing plays.

By the time they were ready to return home, the United States had changed beyond recognition. Hatch and Billops started fresh as artists in New York’s East Village, he as a theater professor at City College of New York (CCNY), and she as an MFA student and ceramics instructor at the same school. “Black Is Beautiful” had become a popular slogan, and around the time the UI’s Black Action Theatre (now the Darwin Turner Action Theatre) was founded, CCNY students shut down their predominantly white campus until the administration agreed to open enrollment.

Hatch’s own horizons had expanded considerably during his travels—but arguably, so had his pupils’. As his classroom became a gathering place for people of myriad cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, his credibility as a white male academic and artist in an Afrocentric milieu would be put to perhaps its greatest test.

Age V - THE JUSTICE

"It was often difficult to work across races," Hatch observed in his Kennedy Center speech. Becoming “full of wise saws and modern instances,” as Shakespeare put it, took him at least three decades. At 40 years old in 1969, Hatch was a well-traveled writer with a PhD—one small star in a galaxy of brilliant but marginalized New York artists. At 70, he’d become an award-winning theater historian, co-founder of one of the globe’s most dazzling archives of Black art.

“When I was enrolled in Brock’s class at Iowa,” he joked, “I proclaimed myself to be a playwright who would never, ever have any use for bibliography or footnotes.” Yet, among his first academic works was The Black Image on the American Stage: A Bibliography (1970). The flurry of scholarship that followed, as well as the vast archive from which each book drew material, owed much of its existence to Hatch’s students.

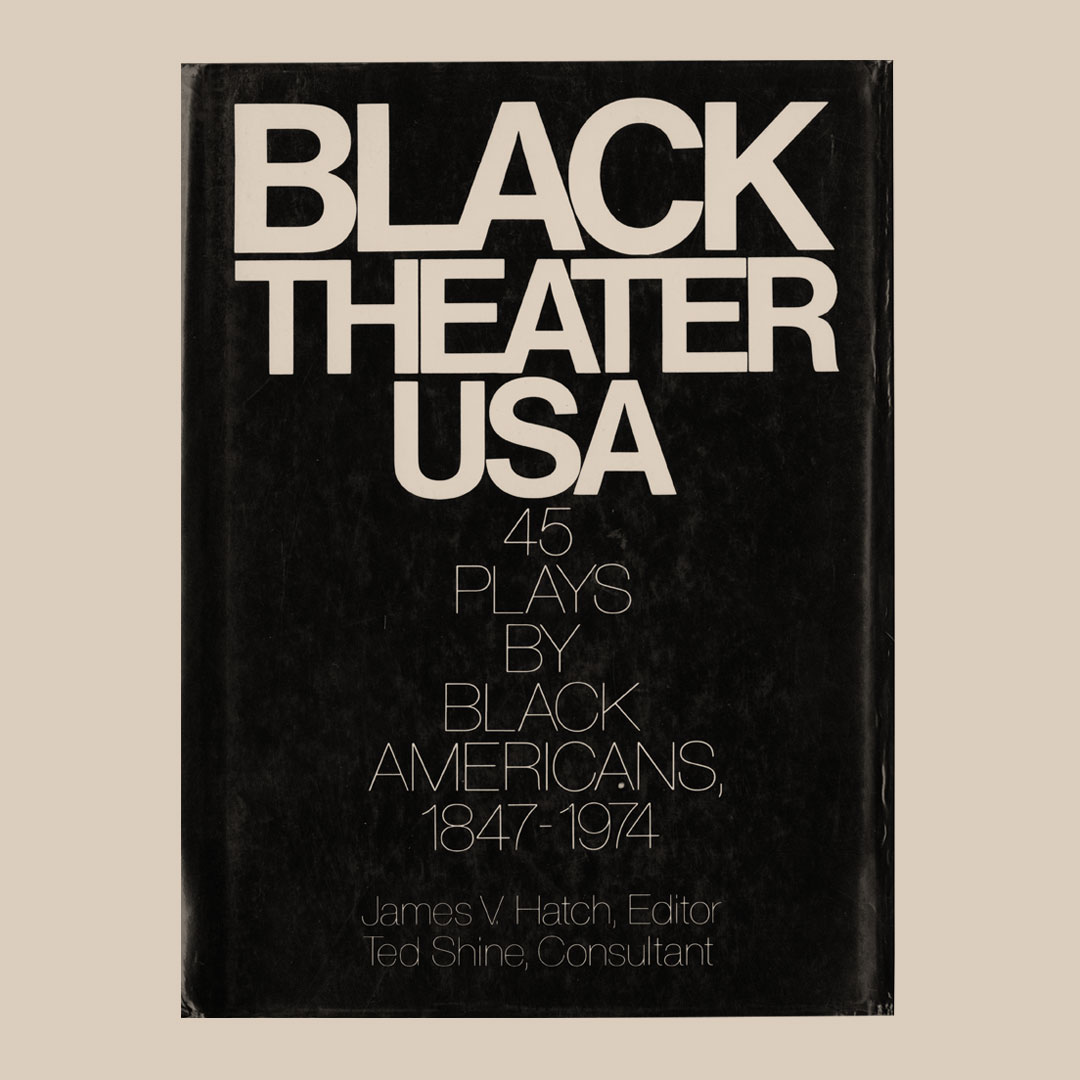

University of Iowa theatre arts classmates Jim Hatch and Ted Shine compiled Black Theater USA, a definitive collection of influential African American drama.

University of Iowa theatre arts classmates Jim Hatch and Ted Shine compiled Black Theater USA, a definitive collection of influential African American drama.

Now that CCNY’s campus had opened its doors to local applicants, the majority of his pupils were Black. When they asked about Black theater history, Hatch wasn’t sure what books to recommend. He soon discovered that, in fact, no definitive text on African American drama had ever been published—and, with his students in mind, he sought to rectify the situation. During summer 1969, he spent months in the New York Public Library reading not only every play by a Black writer, but every play that contained even one Black character. The eventual result was Black Theater USA (1973), the first historical anthology of African American plays, co-edited by Hatch and his former schoolmate Ted Shine.

From then on, Hatch made it his mission to chronicle the pasts of unsung Black artists while they could still share their stories firsthand. His groundbreaking scholarship attracted funding for oral history work from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Billops, who herself had begun to compile Black artists’ memorabilia, joined his efforts, introducing Hatch to old-time Black theater luminaries so Hatch could interview them personally. She helped her partner bridge the cultural barrier; her presence reassured some interviewees who might otherwise question the motives of this unfamiliar white interviewer. Indeed, contemporaries like Black playwright and scholar Loften Mitchell never stopped suspecting Hatch, accusing him of appropriating Black artists’ work to further his academic career. “I sometimes suspected myself of exploitation,” Hatch admitted in front of the Kennedy Center crowd.

Still, he never hesitated to examine the holes in U.S. history where Black artists should be—the fault of what he called “a white racial gaze.” “One may pore over many bio-dictionaries of black ‘achievement’ and find few women and no theatre folk,” Hatch prefaced his and Hill’s A History of African American Theatre, “unless that artist had already won the approbation of white audiences.” From the 1960s onward, he continued to combat this injustice by co-editing books, usually with Black colleagues, like The Roots of African American Drama (1991) and Lost Plays of the Harlem Renaissance (1996), and by completing an award-winning biography of writer Owen Dodson titled Sorrow Is the Only Faithful One. Meanwhile, his and Billops’ collection of artifacts had expanded into a borrowing library they could no longer afford to keep in their East Village apartment.

Cycling through the neighborhood one day, Billops happened upon Hatch’s old UI classmate Richard Schechner (58MA), now a director of experimental theater. When he heard they needed to move, Schechner offered to sell her and Hatch a 4,000-square-foot loft at the corner of Broome Street and Broadway.

In his 2009 interview with Kathy A. Perkins, Hatch described cashing his insurance policy to buy the place sight unseen, and taking the money to Schechner’s nearby scene shop. “I said, ‘I’ve come to buy my loft,’ and he said, ‘Okay.’ I said, ‘I have a check,’ and he took it, looked at it, put it in his pocket, and went back to work.” When Hatch asked for a receipt, Schechner said, “Oh, yeah.” “He reached down, picked up a paper bag of nails, tore a piece out of it, and wrote: Received: $10,000 from—‘What’s your name?’”

In their new loft, which doubled as Billops’ studio and the couple’s arts archive, Hatch was usually the person asking that same question. He and Billops had fallen head-over-heels for oral history, inviting thousands of Black artists to their apartment to answer questions like, “What’s your full name? Where were you born? Who were your parents? What influence did they have on you becoming an artist?”

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Iowa Writers’ Workshop alumna Margaret Walker was among many notable Black artists that Jim Hatch and Camille Billops interviewed for the journal Artist and Influence.

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, UI LIBRARIES UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Iowa Writers’ Workshop alumna Margaret Walker was among many notable Black artists that Jim Hatch and Camille Billops interviewed for the journal Artist and Influence.

Hatch developed a gift for turning interviews into lively conversations. Eventually, he and Billops hosted Sunday-afternoon salons, where Black artists would question each other about their lives on reel-to-reel tape, often in front of a live audience. The resulting recordings included the voices of Dizzy Gillespie, James Baldwin, and Toni Morrison, as well as UI alumni Elizabeth Catlett (40MFA), Margaret Walker (40MA, 65PhD), and James Butcher (41MA).

Some of the transcripts were published in Artist and Influence, the Black arts journal Hatch and Billops curated for two decades. “People would come to us: ‘You need to interview so-and-so,’” said Billops in a 2015 interview with Harlem Cultural Archives, “and we would usually follow it up. We tended to listen to a lot of people, and they did not have to be famous. They had to be interesting.”

Interesting people became a fixture of the Hatch-Billops loft. At the New York Public Library’s 2019 tribute to the couple, George C. Wolfe—Tony Award-winning director of Angels in America (1993) and Bring in ’da Noise/ Bring in ’da Funk (1996)—credited their loft with his survival during his first few years in New York: “I would babysit for their annoying cat, Shongo, who would come over and smack you in your face when it wanted some crunchies. It became my home.”

Wolfe recalled that Hatch, in particular, modeled something important for him: “Watching Jim work all day, every day, on a project ... it became clear to me: Art is a verb. Art is something you work at all the time.”

Age VI - THE PANTALOON

When one realizes that within months of his Kennedy Center address Hatch was diagnosed with dementia, the speech takes on a special poignancy. During the previous decade, he and Billops had added moviemaking to their repertoire, producing seven films—one, Finding Christa, won the 1992 Grand Jury Prize at Sundance—whose common thread was memory.

Hatch had also revisited playwriting

and his home state of Iowa. Since the mid-1990s, he and Billops provided an annual

gift to the UI’s Department of Theatre Arts,

and around 2000, they endowed the Hatch-Billops Scholarship to benefit students of

color. “Jim was also instrumental in sending

Black students our way, especially graduate

students,” says

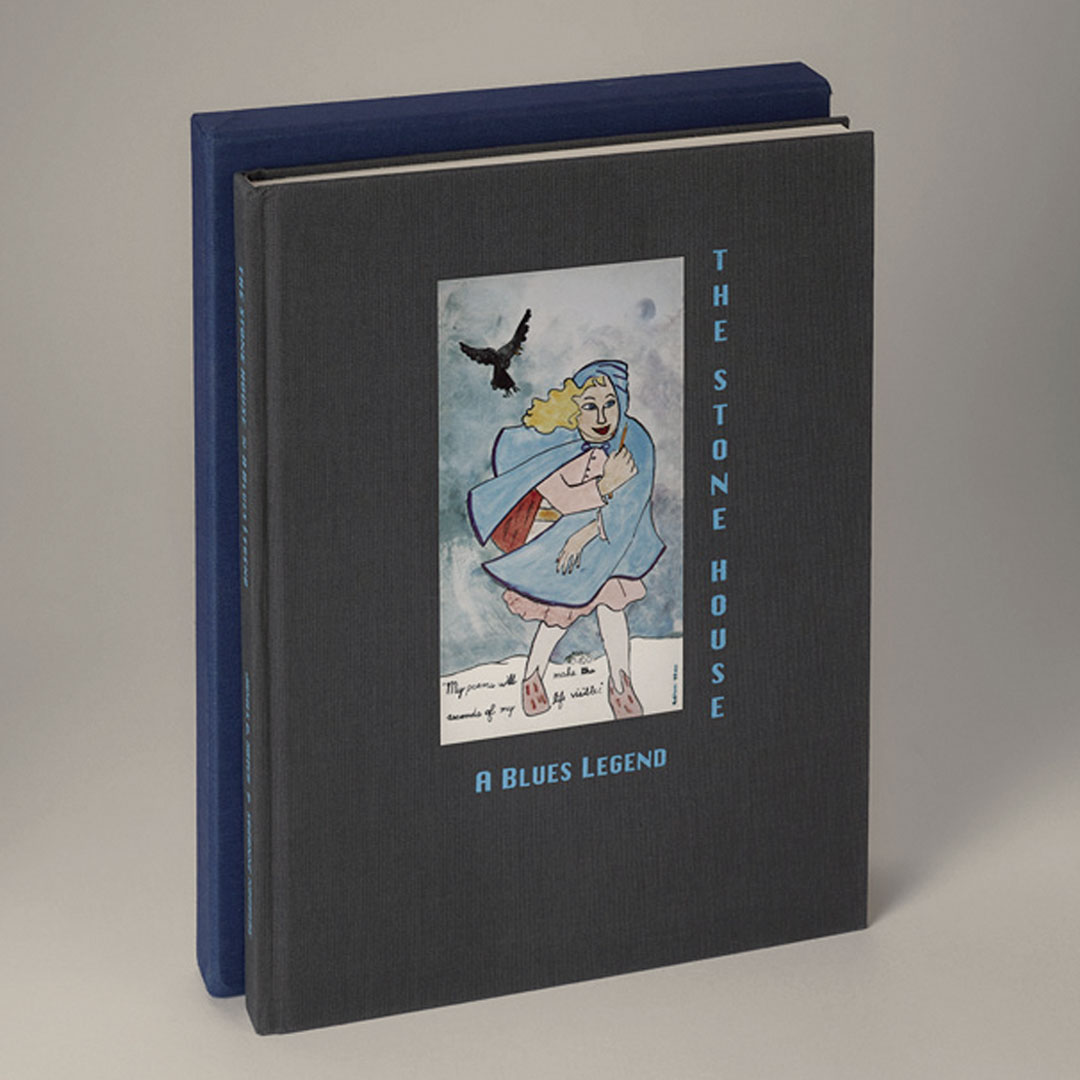

The Stone House, a novel co-written by Jim Hatch, was adapted into Klub Ka, a musical that graced stages in Iowa and New York.

The Stone House, a novel co-written by Jim Hatch, was adapted into Klub Ka, a musical that graced stages in Iowa and New York.

That same year, Hatch co-wrote a novel, The Stone House, with poet Suzanne Noguere. Set alternately in the Egyptian underworld and a blues club named Ka, the story follows an aspiring teenage poet who escapes an abusive home to find her muse. Hatch, Noguere, and theatre arts professor emerita Tisch Jones adapted the book into a play, Klub Ka, which Jones directed at UI’s Main Stage during fall 2000, and again during its six-week run in New York. Hatch’s son, Dion, an Emmy-nominated visual effects supervisor, recorded the performances. The play’s musical director was Billops’ daughter, Christa, to whom Hatch had served as a mentor.

If collecting knowledge had characterized Hatch’s middle age, he now hurried to impart it to a younger generation before it disappeared. His influence inspired lighting designer and theater historian Kathy A. Perkins to write her first book—but when she asked him to be co-editor, Hatch fell back. “He said, ‘Of course not. You can do this by yourself,’” remembered Perkins. “‘You need to go out and make your own reputation.’

Age VII - SANS EVERYTHING

Jim Hatch and his wife, Camille Billops, created an archive at Emory University documenting the history of African American art and culture.

Jim Hatch and his wife, Camille Billops, created an archive at Emory University documenting the history of African American art and culture.

When, in the early 2000s, Hatch and Billops bequeathed most of their loft’s collection to Emory University’s Rose Library in Atlanta, they had accumulated over 25,000 books, tapes, slides, programs, photos, and catalogs by and about Black artists. As the richness of the Billops-Hatch Collection became internationally recognized, Emory celebrated its namesakes with honorary degrees and a 2016 exhibition called Still Raising Hell.

Well into their 80s, the couple had reached their Seventh Age of Man—or, as Shakespeare dubbed it, the “last scene of all.” After Billops passed away in 2019, Hatch lived out his final months among the remnants of their archive—just as he’d joked at the Kennedy Center: “When I leave our loft, it will be feet first, or in a butterfly net.”

For better or worse, Hatch did not live to see how drastically 2020 would change the discipline of theater. It’s possible that public performance, as well as all public interactions, might never feel quite the same. Even so, the many acts of James V. Hatch’s life and their recurring themes—listening, reflecting, asking questions, and amplifying other people’s art— may well demonstrate something vital about how to adapt.

PHOTO COURTESY CASSANDRA JENSEN

PHOTO COURTESY CASSANDRA JENSEN

Cassandra Jensen (20MFA) is a graduate of the UI’s Nonfiction Writing Program, where she incorporated findings from the Camille Billops and James V. Hatch Archives into her MFA thesis about Cold War-era Black theater. A 2017-18 Iowa Arts Fellow and a former nonfiction editor at The Iowa Review, she currently works as a staff editor for a New York nonprofit.