The Artist as Muse

While Elizabeth Catlett was a student at the University of Iowa, world-renowned American Gothic painter Grant Wood instructed her to draw what she knew.

What Catlett (40MFA) knew were the trials and tribulations of being an African American woman in the pre-Civil Rights era. "I decided that I was going to work with the problems of black women," she once told the National Visionary Leadership Project (NVLP), which preserves the stories of notable African American leaders. "I was going to try to make people see them as beautiful, dignified, strong people instead of, as Ralph Ellison says, 'invisible.'"

After becoming one of the first students in the nation to receive a Master of Fine Arts degree when she graduated from the UI School of Art and Art History in 1940, Catlett earned acclaim as an accomplished artist, educator, and civil rights activist. Considered a key African American sculptor and printmaker of the 20th century, Catlett is best known for an extensive and consistent body of work that she honed well into her 90s.

With Catlett's name only growing in renown since her death in 2012, the UI is rediscovering and honoring her legacy. With her artwork displayed prominently across campus, as well as a scholarship and a residence hall established in her name, the UI created a lasting tribute to remember one of its most distinguished alumni—and to inspire future generations of students.

"Our students will be uniquely positioned...to learn about a woman who struggled, who was challenged, who faced adversity in ways I think many of us knew nothing about," UI Vice President for Student Life Melissa Shivers said at the summer 2017 dedication ceremony for Catlett Residence Hall. "Because of her, we have no right to give up. Because of her, we have no right to give in. Because of her, we know that anything is possible. And because of her, we can."

Catlett's story of perseverance resonates with many current UI students, including a poet who helps African American artists find their voice, an engineer who melds science and art, a printmaker who's earned a scholarship in her name, and a performer who honors her memory through the Arts Living Learning Community inside Catlett Residence Hall. These student artists from across campus now carry her torch.

Raising One Voice

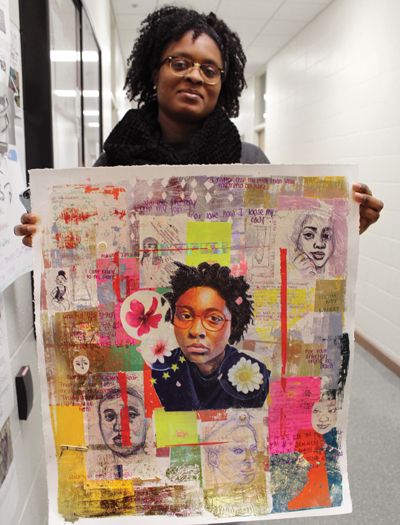

Photo courtesy Reanna Lewis

Reanna Lewis

Photo courtesy Reanna Lewis

Reanna Lewis

Reanna Lewis stepped up to the microphone and began pouring out her heart.

Before a sea of strangers at her On Iowa! orientation, Lewis shared a poem she wrote earlier that day. Soon she noticed a group of supportive students in the front row. "They got excited when I said it was my first open mic," says Lewis, a first-generation transfer student now in her third year at Iowa. "Their energy attracted me from the start."

Originally from Los Angeles, Lewis longed to find community at the UI, and she found it in the front row at orientation with students from Black Art; Real Stories.

BARS began in fall 2015 as a platform to showcase the artistic talents of African American students at the UI. In addition to creating community based on shared identity and experiences, the group publishes an undergraduate literary magazine each spring that showcases the voices of historically marginalized students. Lewis says, "No student, no matter their race or nationality, should ever feel unheard, and that is one of the reasons why BARS was created."

Lewis serves as editor-in-chief of the 2018-19 BARS literary magazine but doesn't limit her artistic expression to the page. "I've been painting since I was 10. I've been singing and dancing since I was about 7," says the English and creative writing major. "This is my life."

Though Lewis uses her art to explore universal themes such as faith, love, and family, she also tackles issues especially resonant in the African American community. After hearing about cases of police brutality against minorities in the U.S., Lewis put the heaviness she felt into words. "I was very frustrated," she says. "I didn't know how to channel my emotions, so I just started writing."

Through the support and feedback of the BARS community, Lewis says she's gained the confidence to become a better performer and artist. With the encouragement of her peers, she recently created an online multimedia portfolio, performed at poetry slams across the region, and finished the manuscript for her first poetry book.

As Lewis looks toward her future, she also reflects on the African American Hawkeyes who came before her—such as Catlett—who contributed to making Iowa a more welcoming and inclusive campus. "I think about how challenging it must have been, especially as a black woman. You have to have a different kind of strength and undergo enlightenment within yourself to be able to find a way to express yourself in a positive light, but also inspire others in the process," says Lewis. "It makes me proud to be a black woman here and to stand and continue on from other people's sacrifices and hard work."

A Fusion of Art and Science

PHOTO COURTESY DEANNE WORTMAN

PHOTO COURTESY DEANNE WORTMAN

Gifted in both science and art, Gabrielle Kershaw says she views the idea of being either left-brained or right-brained as a false dichotomy. So when it came time for the Sicklerville, New Jersey, native to choose a college, she searched for a place that allowed her to explore the best of both worlds.

Now a senior immersed in the UI College of Engineering's Virginia A. Myers NEXUS of Engineering and Art program, Kershaw says she's found "a haven for creativity to flourish." The innovative program, launched in fall 2015, encourages interdisciplinary learning and collaboration by requiring undergraduate engineering students to take at least three semester hours in the creative arts. It also provides limitless opportunities for engineers and artists to interact and share their complementary perspectives.

"NEXUS has made me a better engineer by making me more open to try different methods of problem-solving," says Kershaw, a chemical engineering major and president of the UI chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers. "It also helped me see how important art is to STEM. Many of the greatest structures in the world were created by artists."

Between classes, Kershaw spends time in the college's NEXUS Studio at the Seamans Center for the Engineering Arts and Sciences. Inside the hands-on learning classroom, she participates in workshops and community projects that combine practical principles of engineering with the beauty of the arts. Kershaw and other students test the bounds of their imagination among puzzles and models; a deconstructed piano with exposed levers, hammers, and wires; and hot foil stamp-making machines invented by the former UI professor and printmaker for whom the program is named, Virginia A. Myers. Like Catlett, Myers helped break the traditional barriers between art and engineering.

Led by Myers protégé Deanne Wortman (70BFA, 76MA, 98MFA), the NEXUS program takes pride in introducing engineering students such as Kershaw to the accomplishments of past innovators, ranging from Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo to Catlett and Myers. Weaving history into the NEXUS art and science workshops, Wortman says: "We take students back to the question, 'How did we get here?'"

That question lingered in Kershaw's mind as she contributed art to Fractals of Identity, a Seamans Center display that invites engineering students to reflect on the building blocks that make them who they are. One of Kershaw's collages focuses on her identity as an African American woman, honoring her parents and other trailblazers like Catlett. "It symbolizes the work of people who came before me—their courage, sacrifice, and discipline that put me in the position that I am in now," says Kershaw, who plans to become an engineer and art director. "They kept me going throughout college and make me excited for what blessings may be in store for the future."

A Community for the Arts

PHOTOS: JUSTIN TORNER/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Catlett Residence Hall

PHOTOS: JUSTIN TORNER/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

Catlett Residence Hall

Every day on his way to class, UI freshman Nicholas Currant walks past Catlett's photo and Totem sculpture in the lobby of Catlett Residence Hall and feels emboldened to pursue his dream of a career in the arts. "It's really inspiring to think that anyone who passes through here with hard work and dedication can get there one day," says Currant, a vocal performance, theatre arts, and marketing major from Bondurant, Iowa.

Currant isn't the only one encouraged by the daily reminders of a UI alumna who successfully walked the path before him. As the newest and largest dormitory on campus, Catlett Residence Hall houses 1,049 students—including more than 60 involved in its Arts Living Learning Community. Currant serves as president of the residence hall and as a leader in the Arts Living Learning Community where students interested in the visual, creative, and performing arts can collaborate and support one another's endeavors while living on the same floor. "We want to keep the memory of Elizabeth Catlett alive not just in the name of the building, but also in the residents who pass through here," says Currant.

In this dynamic atmosphere, Currant expands upon his understanding of the arts alongside musicians, actors, filmmakers, dancers, and other creatives. The aspiring musical theater performer has acted in a cinema major's film project, planned an outing for his hallmates to watch Hancher's production of Les Misérables together, and cheered on fellow student artists at their performances and exhibit openings.

Living learning community members also are required to take an arts-related first-year seminar to cultivate their appreciation for the creative process. This past fall, Currant and some of his hallmates took an Arts Encounters course that included a unit on Catlett—of special interest to those living in the eastside residence hall that overlooks the Iowa River. Currant says, "We gained a new appreciation for what our building was meant to represent."

Passing the Baton

When printmaker Dayon Royster earns his MFA degree in spring 2019, he will become the latest in a long line of accomplished UI artists to follow in Catlett's footsteps. In fact, it was her generosity that enabled Royster (18MA) to attend graduate school in the first place.

Royster is one of five students since 2012 to receive the Elizabeth Catlett Scholarship, given to a UI School of Art and Art History printmaking student who is African American or Latino. Catlett used proceeds from the UI Stanley Museum of Art's purchase of her artwork to support the education of future Iowa students—including Royster, who says he wouldn't have considered grad school without financial aid.

Originally interested in becoming a nutrition scientist, the Richmond, Virginia, native switched to art after being challenged and stimulated by a design course he took to fulfill an elective requirement at East Carolina University. He soon became enamored with the experimentation and variations of color and texture inherent to printmaking.

Motivated to pursue the art form at a higher level, Royster followed his mentor Heather Muise's recommendation to attend graduate school at Iowa—ranked third in printmaking among the nation's public universities by U.S. News & World Report. It's where Muise's mentor, UI professor Anita Jung, now serves as his faculty advisor. "The University of Iowa has a huge presence in the printmaking world," Royster says about the prestigious program, established in the late 1940s by famed artist and educator Mauricio Lasansky. "There's this crazy lineage that happens in the printmaking world, and now I'm part of that lineage."

From the moment he arrived on campus, Royster says he felt at home. He was impressed by the quality of the work produced by UI artists, the friendliness of the students, and the world-class print shop housed in the new Visual Arts Building. Royster says he enjoys the opportunity to not only learn from fellow printmakers, but also from other visual artists, writers, poets, bookmakers, engineers, and scientists across the university. "We're constantly seeing what everyone's working on and bouncing ideas off one another," he says. "This is a community that's very encouraging and wants to see everyone do the best they can, so they're not afraid to give you their honest opinions."

That feedback helped Royster improve his technique and gain confidence in his work. It's also made him a better instructor of Introduction to Printmaking for art majors and the perennially popular Elements of Art course for non-majors. As he teaches printmaking processes passed down through generations, Royster finds satisfaction in realizing his students are becoming as passionate about the art form as he is.

Like Catlett, Royster wants to continue to inspire others as an artist and educator. "Because printmaking is so process-based, I get a lot of questions that I absolutely love answering," he says. "The excitement I get from that has exponentially increased by teaching a larger number of people."

Catlett at Iowa

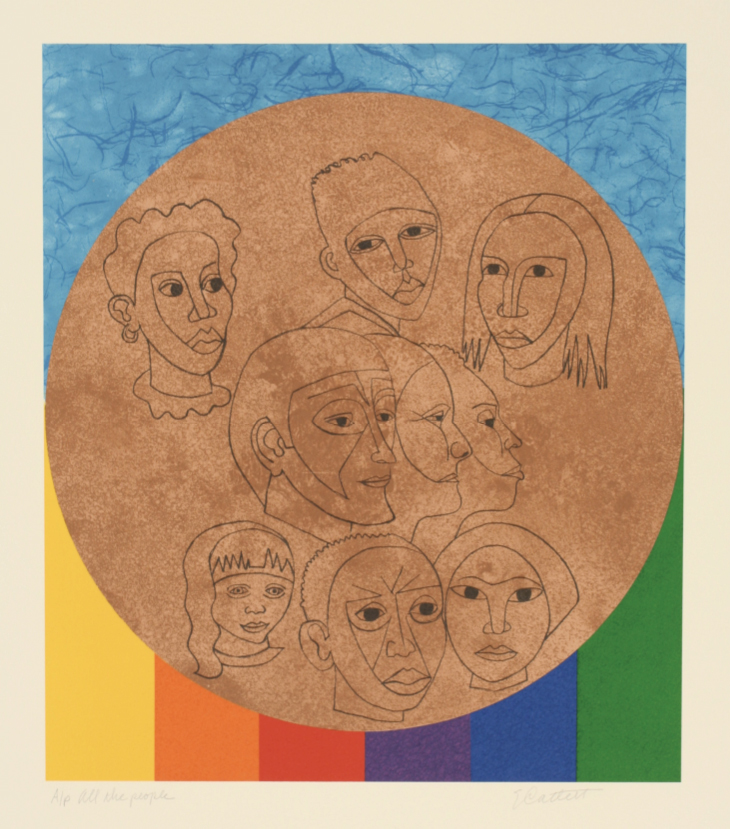

ELIZABETH CATLETT (AMERICAN, 1915–2012),

ALL THE PEOPLE, FROM FOR MY PEOPLE, 1992,

LITHOGRAPH ON PAPER,

22 3/4 X 18 3/4 IN. (57.79 X 47.63 CM),

UNIVERSITY OF IOWA STANLEY MUSEUM OF ART,

MUSEUM PURCHASE, 2006.74G

© 2019 CATLETT MORA FAMILY TRUST / LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS

RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY

Among the

Catlett works in the

UI Stanley Museum

of Art's collection is

this lithograph that

depicts scenes from

her former college

roommate Margaret

Walker's (40MA, 65PhD)

acclaimed UI thesis,

For My People, a 1942

poem celebrating the

inner strength of African

Americans. "She would

wake me up at night

and read me her poem,"

Catlett recalled to the

National Visionary

Leadership Project, "and

I would be so sleepy, I

didn't even know what

she was talking about."

ELIZABETH CATLETT (AMERICAN, 1915–2012),

ALL THE PEOPLE, FROM FOR MY PEOPLE, 1992,

LITHOGRAPH ON PAPER,

22 3/4 X 18 3/4 IN. (57.79 X 47.63 CM),

UNIVERSITY OF IOWA STANLEY MUSEUM OF ART,

MUSEUM PURCHASE, 2006.74G

© 2019 CATLETT MORA FAMILY TRUST / LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS

RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY

Among the

Catlett works in the

UI Stanley Museum

of Art's collection is

this lithograph that

depicts scenes from

her former college

roommate Margaret

Walker's (40MA, 65PhD)

acclaimed UI thesis,

For My People, a 1942

poem celebrating the

inner strength of African

Americans. "She would

wake me up at night

and read me her poem,"

Catlett recalled to the

National Visionary

Leadership Project, "and

I would be so sleepy, I

didn't even know what

she was talking about."

Education always was important to Elizabeth Catlett's family. Catlett's father was a Tuskegee Institute professor, and her maternal grandparents were former slaves who ensured all eight of their children pursued higher education. Raised in Washington, D.C., Catlett expressed an early interest in art—once carving an elephant out of a bar of soap in high school.

Denied admission to Carnegie Institute of Technology due to her race, Catlett instead graduated from art school with honors in 1935 from Howard University, a historically black college. After a few years of teaching, she pursued graduate school at the UI on the recommendation of friends who knew the school's history as the first public university in the U.S. to admit women and men on an equal basis and the first to admit students regardless of race.

In summer 1938, Catlett traveled by train from Washington, D.C., to Iowa City. She found a UI education attainable at $75 a semester but was more drawn to the idea of studying under Grant Wood—an established artist who gained fame in 1930 from his iconic painting, American Gothic.

Catlett immediately connected with Wood, her UI painting professor who also served on her thesis committee. "Grant Wood was a very generous teacher," she once told the UI's Arts & Sciences magazine, "and he influenced all my work."

Although Wood proved a faithful mentor, Catlett still faced steep challenges at Iowa. "I'd lived in an African American culture my whole life," she once told the National Visionary Leadership Project (NVLP). "In Iowa City, I suddenly was living among white people, but I still couldn't do things like live in the dorms."

A preliminary sketch from

Elizabeth Catlett's 1940 thesis

project, Negro Mother and Child

A preliminary sketch from

Elizabeth Catlett's 1940 thesis

project, Negro Mother and Child

UI residence halls didn't open to black students until 1945. To overcome that barrier, Catlett built friendships with the eight other black women on campus while living in boarding houses run by local African Americans. Catlett also found support in Vivian Trent (34BA), a UI alumna who allowed Catlett to wait tables for meals at Vivian's Chicken Shack—one of the few fully integrated restaurants in town.

But Catlett spent most of her time at Iowa in the studio. Inside the UI Art Building, she mastered the techniques she would use to create her thesis project—a limestone sculpture of a mother embracing her child that won first prize at the 1940 American Negro Exposition in Chicago.

The art department didn't have courses on metal manipulation at the time, so Catlett took the initiative to enroll in an undergraduate course in bronze casting at the UI College of Engineering. Those two semester hours turned out to be problematic for art department head Lester Longman. Near the end of her final semester, Longman told her she couldn't earn her MFA in sculpture because she had taken the undergraduate engineering course and not printmaking—leaving her two hours shy of the degree. But Catlett argued she had entered Iowa with four hours of graduate credits from Howard University.

As Catlett joked to the NVLP: "We were going to do a little play in Wood's class where Michelangelo came up for his MFA and Mr. Longman would say, 'But you haven't had any printmaking.'"

The issue remained unresolved until the day of her thesis defense. Behind closed doors, five members of the art department debated whether to award her the degree. Catlett feared she would have to pack her bags and go home empty-handed, but Wood promised to be her champion. It was one of his last actions as a UI professor before his death in February 1942 from pancreatic cancer.

"I think the university has a responsibility to acknowledge her work. She was a pioneer." - Kathleen Edwards

"I waited for the longest time," Catlett told Arts & Sciences. "Finally, Grant Wood came out and said, 'Congratulations. You have earned your degree.'"

Catlett made history as the first African American woman in the country to receive an advanced degree for artistic achievement. Alongside UI sculpture professor Harry Edward Stinson (21BA, 40MFA) and one other student, she was the first person to receive an MFA in sculpting at the UI. Says retired UI Stanley Museum of Art curator Kathleen Edwards, who wrote a chapter on Catlett in Invisible Hawkeyes: African Americans at the University of Iowa During the Long Civil Rights Era: "The whole thing just screams of her ability to persevere and fight for what was hers."

Over the past two decades, Edwards has led the charge to ensure Catlett's example shines brightly at Iowa. One of her first acts as a UI Stanley Museum of Art curator was to add Catlett's artwork to the university collection. In 2002, the museum's Print and Drawing Study Club raised enough money to purchase one of Catlett's most iconic prints, Sharecropper (1952). Edwards then visited Catlett's home in Cuernavaca, Mexico, in 2006 to purchase another 28 prints for the UI Stanley Museum of Art that represent her range.

"I think the university has a responsibility to acknowledge her work," Edwards says of Catlett, a 1996 UI Distinguished Alumni Award winner. "She was a pioneer."

Catlett's trailblazing spirit served her well as she later campaigned for her black students at Dillard University in New Orleans to enter segregated art museums, supported social and political causes from her home in Mexico, and created works that grace the collections of major institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Today, local students of all ages can also study Catlett's artwork in the Stanley Museum of Art's Visual Classroom, housed at the Iowa Memorial Union. During the fall 2018 semester, Catlett's prints enriched a guest music lecture and classes on poetry, creative writing, literature, and art. Because the prints are owned by a public university, they're accessible for anyone to view.

In addition to the prints, two of Catlett's sculptures inspire UI students on campus—Stepping Out at the Iowa Memorial Union and Totem at Catlett Residence Hall. Catlett's eldest son, musician Francisco Mora Catlett, spoke at the opening of Catlett Residence Hall in 2017 and returned to the UI in February 2019 with his wife, Danys "La Mora" Pérez, founder and artistic director of Oyu Oro Afro-Cuban Experimental Dance Ensemble in New York, for a music and dance residency. "I truly believe that Iowa was the strongest part of [my mother's] foundation as an artist," says Mora Catlett. "She's definitely a large inspiration for students, and her legacy is a kaleidoscope that will continue to evolve as we advance as a society."

As Catlett's story becomes better known on campus, it opens the door to more opportunities for UI students. "The story of Catlett's Iowa experience is important to share with students today," says Edwards. "Truly, we all can learn from and be inspired by her example."