COVID-19 Crisis Brings Renewed Interest in Iowa's Spanish Flu Detective

GRAVESITE PHOTO COURTESY JOHAN HULTIN; CEMETERY PHOTO: ANGIE BUSCH ALSTON;

LABORATORY PHOTO COURTESY JOHAN HULTIN; VIRUS PHOTO: C. GOLDSMITH /PUBLIC HEALTH IMAGE LIBRARY

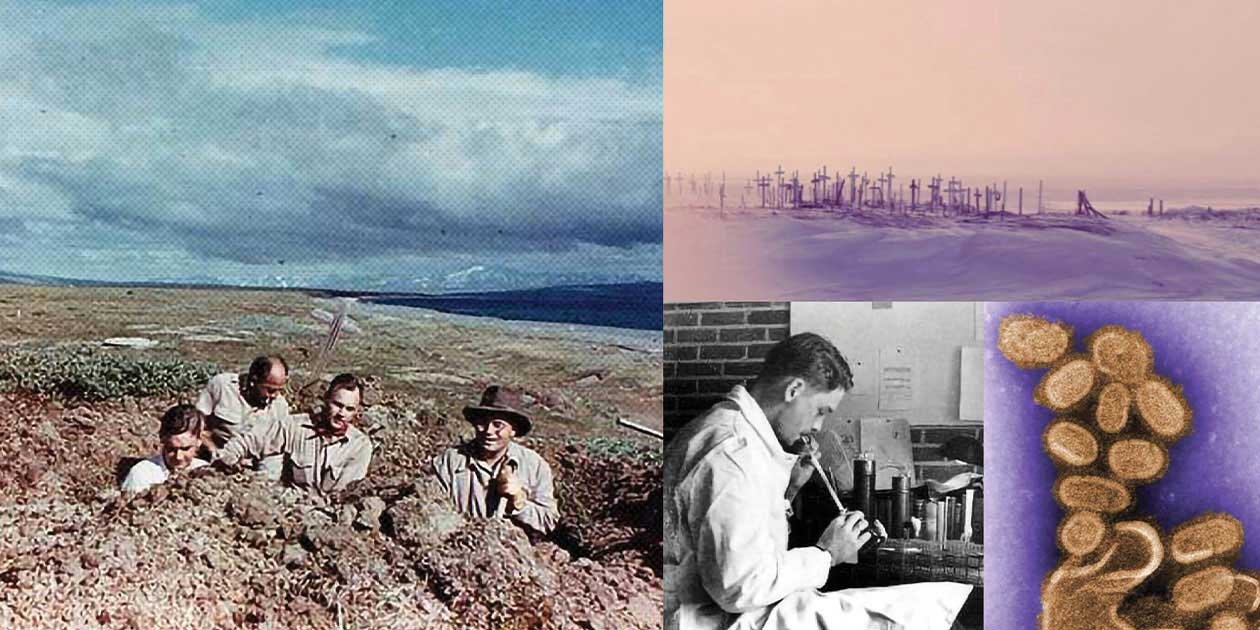

Top left: Johan

Hultin (far left) and

his team excavate

the burial site in

Brevig Mission,

Alaska, during his

first visit in 1951.

Top right: The

mass grave where

72 people were

buried after the 1918

pandemic ravaged

the small village.

Bottom center:

Hultin in the

laboratory in 1951.

Bottom right: A

colorized image of

the 1918 virus taken

by a transmission

electron microscope.

GRAVESITE PHOTO COURTESY JOHAN HULTIN; CEMETERY PHOTO: ANGIE BUSCH ALSTON;

LABORATORY PHOTO COURTESY JOHAN HULTIN; VIRUS PHOTO: C. GOLDSMITH /PUBLIC HEALTH IMAGE LIBRARY

Top left: Johan

Hultin (far left) and

his team excavate

the burial site in

Brevig Mission,

Alaska, during his

first visit in 1951.

Top right: The

mass grave where

72 people were

buried after the 1918

pandemic ravaged

the small village.

Bottom center:

Hultin in the

laboratory in 1951.

Bottom right: A

colorized image of

the 1918 virus taken

by a transmission

electron microscope.

In 1997, Iowa-trained pathologist Johan Hultin trekked into the Alaskan wilderness in search of the most prolific killer of the 20th century. Armed with a pair of his wife's garden shears, the retired scientist and adventurer, then 72, arrived at a mass grave outside a remote oceanside village named Brevig Mission.

There, buried atop a hillside encased in permafrost, were the bodies of dozens of residents of the tiny town who died in the 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic, commonly known as the Spanish Flu. Hultin was there to unearth the secrets of a pandemic that killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide and puzzled scientists decades after it had run its course.

Today, 23 years after his expedition changed science's understanding of the 1918 flu, Hultin is back in the news amid a current pandemic and renewed interest in its predecessor. In May, Sports Illustrated chronicled the exploits of the former mountain climber and skier whom the magazine describes as "part Indiana Jones, part Anthony Fauci."

The Swedish-American researcher made his first journey to Alaska as an Iowa graduate student in microbiology in the early 1950s. In search of preserved samples of the 1918 flu, Hultin and a team of UI colleagues obtained permission from village elders to excavate the Brevig Mission burial site. After two days of digging, Hultin removed lung tissue from several frozen bodies. Though the retrieval was successful, Hultin was ultimately unable to isolate the virus from his samples at his lab back in Iowa.

Hultin went on to enjoy a long career as a community pathologist in San Francisco, but his interest in the 1918 flu was rekindled in the 1990s when he read a journal article about attempts to sequence the virus' genome. Partnering with the latest generation of researchers, he returned to Alaska 46 years after his first visit to once again exhume the burial site. With the help of his wife's pruning shears, he extracted the lungs from a woman nicknamed Lucy and shipped the samples in preserving fluid to government scientists. This time his efforts paid off. Lucy's well-preserved tissue helped researchers eventually sequence the 1918 flu's genome, revealing that the virus was a mutated form of bird flu, among other key findings.

Now 95, Hultin lives in Walnut Creek, California. In 2009, the UI presented him with an honorary Doctor of Science degree. As he told Iowa Alumni Magazine in 2005, "You can trace the story of the reconstruction of the 1918 flu virus all the way back to the microbiology lab at the University of Iowa."