If You Write It: The University of Iowa Author Who Inspired the Field of Dreams

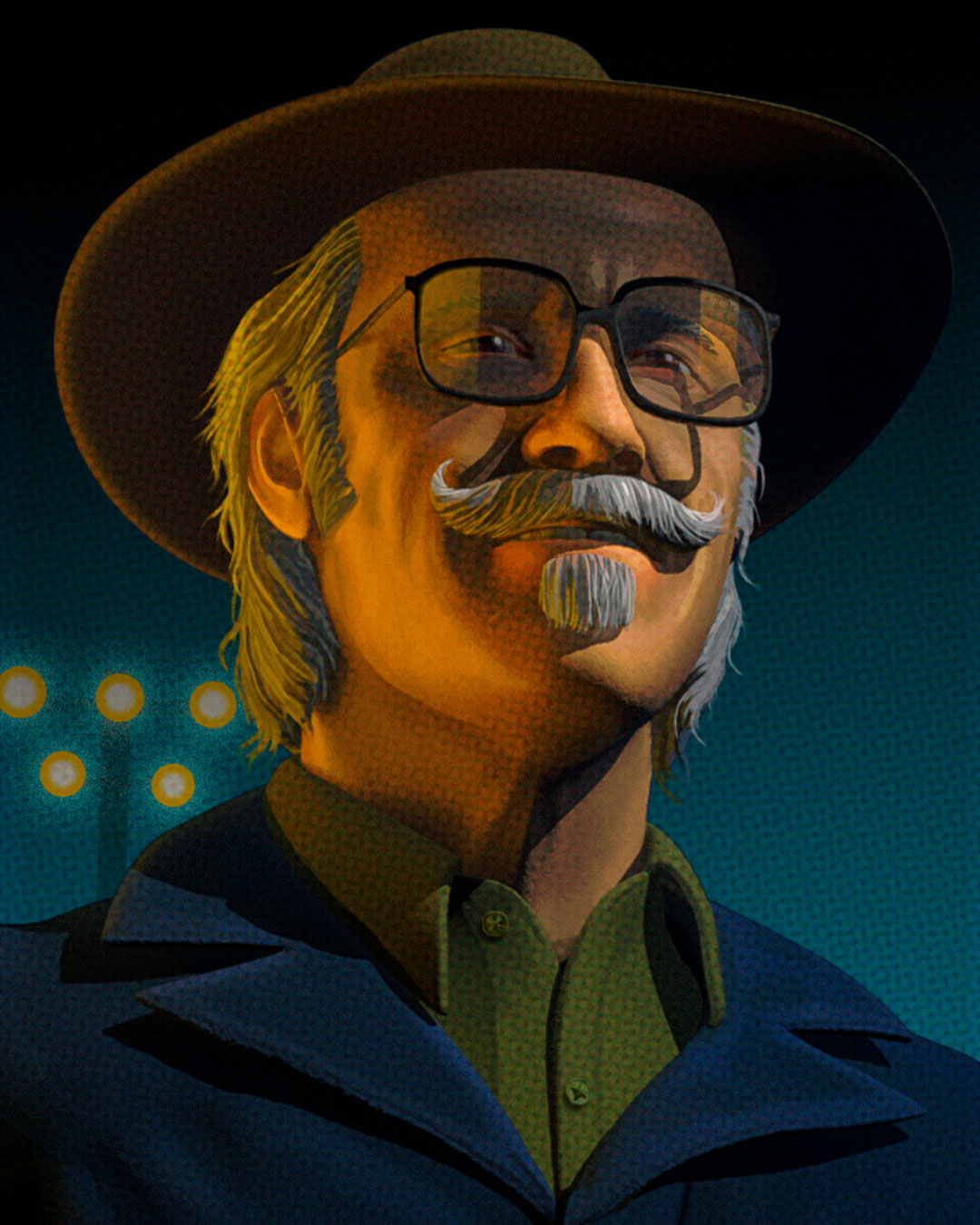

ILLUSTRATION: Tavis Coburn

W.P. Kinsella

ILLUSTRATION: Tavis Coburn

W.P. Kinsella

I came to Iowa to study, one of the thousands of faceless students who pass through large universities, but I fell in love with the state. Fell in love with the land, the people, the sky, the cornfields, and Annie. —The character Ray in Shoeless Joe, by W.P. Kinsella

In August 1976, a 41-year-old aspiring writer named Bill Kinsella boarded a bus in Langley, British Columbia, and set out for graduate school somewhere in the whispering farm fields of Iowa. A former restaurant owner, insurance worker, and taxi driver, Kinsella was ready for a new chapter after years of unfulfilling work and the end of his second marriage.

It wasn't some mysterious voice that beckoned Kinsella to the University of Iowa. But he was called by a persistent dream: to become a professional writer. The Canadian had gained admission to the prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop, where he would spend two years honing his voice as a storyteller while clashing with an academic culture that never quite suited him. Kinsella (78MFA) would write the lyrical short story "Shoeless Joe Jackson Comes to Iowa" while living in Iowa City and teaching undergrads in the English-Philosophy Building. W.P. Kinsella, as Bill became known to the publishing world, eventually turned that tale about baseball-playing ghosts into his best-selling 1982 novel Shoeless Joe, which was adapted for the big screen in 1989 as Field of Dreams.

Today, almost four years after Kinsella's death, the book and film are revered classics—love letters to Iowa, literature, and baseball. Like Grant Wood's American Gothic or Meredith Willson's The Music Man, Kinsella's fable has become part of Iowa's cultural heritage. The American Film Institute named "If you build it, he will come," as one of its 100 greatest movie quotes. "Is this heaven? No, it's Iowa" remains an unofficial state motto. And to this day, no one with a beating heart can hear Kevin Costner as Ray Kinsella say, "Hey, Dad, want to have a catch?" and not reach for the tissues.

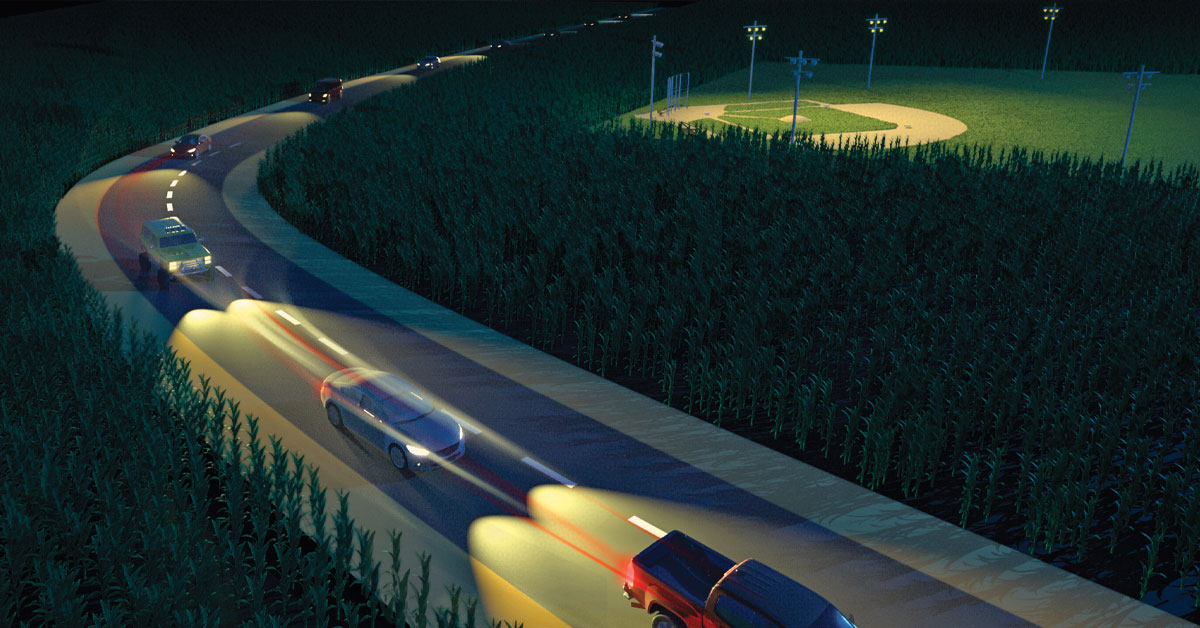

This summer, in testament to the story's lasting hold on our imagination, Major League Baseball is scheduled to host its first-ever game at the Field of Dreams movie site outside of Dyersville, Iowa (barring postponement due to the pandemic). Two of baseball's most tradition-steeped teams, the Chicago White Sox and New York Yankees, plan to play in a temporary 8,000-seat ballpark carved out of the cornfields where director Phil Alden Robinson brought W.P. Kinsella's words to life. Like in the film, cars may stream into the farm from all corners of the country and gather under the lights on a summer night.

The real-life story behind the book and film is filled with the same kind of serendipity that was a hallmark of Kinsella's storytelling.

Growing up is a ritual—more deadly than religion, more complicated than baseball, for there seem to be no rules. Everything is experienced for the first time. But baseball can soothe even those pains, for it is stable and permanent, steady as a grandfather dozing in a wicker chair on a vera ndah. —Ray in Shoeless Joe

As detailed in the recent biography Going the Distance: The Life and Works of W.P. Kinsella by William Steele, Kinsella didn't play baseball as a kid. But like a glove snatching a whizzing line drive, the game caught his imagination at an early age. Kinsella was born on May 25, 1935, the day Babe Ruth hit the final three home runs of his career. An only child who was homeschooled, he had few playmates. He grew up listening to the stories his father told about baseball on the family's remote farmstead in Alberta, Canada. John Kinsella, who had played semi-pro ball while working odd jobs and traveling the U.S., would tell young Bill about the time he saw the infamous Black Sox—the Chicago White Sox team that allegedly threw the 1919 World Series.

Baseball may be a national pastime in the U.S., but the game also has a proud history in Canada. In 1946, when the Kinsellas moved to Edmonton, Bill attended his first semi-pro game and listened to the St. Louis Cardinals win the World Series on the radio. Kinsella, who battled various illnesses throughout his childhood, devised an elaborate pen-and-paper baseball game he could play by himself with dice. In eighth grade, he wrote his first piece of fiction, a story about murder at a ballpark called "Diamond Doom."

Kinsella was in his final year of high school when his father was diagnosed with stomach cancer. Bill was not particularly close with his dad, and he and his mother, Olive, rarely spoke of the gravity of John's situation. After months of declining health, John died the week of his son's final exams.

Young adulthood was marked by a series of tedious jobs and romantic entanglements. Kinsella married twice, had two daughters, and eventually opened his own Italian restaurant in Victoria. All the while, Kinsella wrote stories in his free time and dreamed of the day he could become a full-time author. In his mid-30s, Kinsella enrolled at the University of Victoria to study creative writing. There he took classes from author and Iowa Writers' Workshop alumnus W.D. Valgardson (69MFA), who wrote him a glowing letter of recommendation to the UI's renowned MFA program. Meanwhile, Kinsella began imagining the first of what would become dozens of short stories and books featuring indigenous characters set on the fictional Hobbema Reserve.

The move from western Canada to Iowa for graduate school was a fateful one. Kinsella quickly fell in love with the state and its "rolling fields of corn, the dense humidity, the tall bamboo canes thick as hoe handles," as he once said in an essay for Sports Illustrated. "I had never seen the dazzle of fireflies before. I also loved the intimacy of the Iowa River where it snaked, green and lazy, across the University of Iowa campus. ... I loved the town, the Prairie Lights bookstore, the small restaurants and the magnificent old homes, one of which Flannery O'Connor [47MFA] lived in when she was a student at the workshop."

His affection for Iowa City didn't extend to the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Ever an iconoclast who became increasingly disdainful of academia—later coming to a head during his miserable tenure as an English professor at the University of Calgary—Kinsella was disappointed by the workshop's lack of deadlines and loose structure at the time. He felt unsatisfied with the lack of substantive feedback he received from his peers and with the quality of work of many of his undergraduate students.

"When he showed up at Iowa, he was in his 40s, and in his mind he'd wasted two decades in jobs he hated," says Steele, Kinsella's biographer, who befriended the author in his final years. "He had very little sympathy for those who didn't want to come in and grind it out and work. So that part was frustrating. But he did fall in love with Iowa. He told me not long before he died that Iowa was one of the most beautiful places he'd ever lived."

Still, Kinsella's time at the workshop was productive. Renting a room in an old house at 619 N. Johnson St., he cranked out one short story after another. In spring 1977, he published his first collection of indigenous stories in Canada titled Dance Me Outside, which was a critical success. Kinsella also joined a group called the Iowa City Reading Series that met at College Green Park, took poetry and journalism classes, and met his third wife, Ann Knight, in a writing course.

During his second year of graduate school, Kinsella began work on a new story inspired by Iowa City, the 1919 Black Sox, and his complicated relationship with his father. It was the story that would change his life—and Iowa—forever.

Three years ago at dusk on a spring evening, when the sky was a robin's-egg blue and the wind as soft as a day-old chick, I was sitting on the verandah of my farm home in eastern Iowa when a voice very clearly said to me, "If you build it, he will come." —Ray in Shoeless Joe

The idea for Shoeless Joe materialized like a phantom ballplayer from the corn during Kinsella's final semester at Iowa. "I wondered, 'What would happen if Shoeless Joe Jackson came back in this time and place, which was Iowa City in the spring of 1978?'" he once explained its origin. Jackson was the White Sox's star outfielder whose role in the alleged game-fixing of the 1919 World Series has been debated ever since. In Kinsella's 20-page short story, an Iowa farmer hears a voice compelling him to build a baseball field that conjures Shoeless Joe back to the world of the living, allowing him to play the game from which he was unjustly banned.

ILLUSTRATION: Tavis Coburn

Shoeless Joe Jackson

ILLUSTRATION: Tavis Coburn

Shoeless Joe Jackson

Kinsella read the story, titled "Shoeless Joe Jackson Comes to Iowa," aloud for the first time at the Iowa City Creative Reading Series a week before leaving Iowa City. He'd accepted a teaching position at the University of Calgary that would begin in the fall. The following year, the piece appeared in an anthology of short stories, and an advanced review in Publisher's Weekly caught the eye of a young editorial assistant named Larry Kessenich at Houghton Mifflin. After reading just a brief synopsis, Kessenich urged Kinsella to turn his short story into a novel.

Under Kessenich's guidance, Kinsella completed the 300-page novel in just nine months. Kinsella began with the working title The Oldest Living Chicago Cub, sparked by a conversation he had with an 87-year-old he'd met on the street in Iowa City who claimed to be just that. With his original short story serving as the opening chapter, Kinsella expanded on the tale of the struggling corn farmer, whom he named Ray Kinsella, and the baseball diamond he builds outside Iowa City. Bill Kinsella later said his protagonist wasn't named after him; instead, he had borrowed the name from a character in an obscure J.D. Salinger story that he'd stumbled across while studying at the UI. Kinsella incorporated both the supposed oldest living Cub, whom he called Eddie Scissons, and Salinger in his story.

In the book, Ray travels from Iowa to New Hampshire to track down Salinger, the famously reclusive author. While writing it, Kinsella and then-wife, Knight, made a trip to the East Coast, where they drove through what they called "Salinger Country" in New Hampshire. Along the way they read aloud from The Catcher in the Rye and stopped at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

The couple later traveled to Chisholm, Minnesota, the hometown of a little-known player named Archibald "Moonlight" Graham whom Kinsella had read about in a baseball almanac. Graham had appeared in just one major league game in 1905 and never came to bat. Kinsella and Knight learned how he later became his small town's beloved doctor, and the author immortalized him as a key character in the book. Back in Iowa City, Kinsella talked with a local farm owner about his corn growing methods to ensure his scenes were accurate. "He would always read his work out loud to Ann," Steele says. "He said, 'I know I'm on to something special; this is really good.'"

Kinsella submitted his final manuscript with the title The Kidnapping of J.D. Salinger, and Houghton Mifflin published the book in 1982 with the revised title Shoeless Joe. Readers and critics alike were charmed by Kinsella's use of magical realism to tell a story about baseball and redemption. As a reviewer for Sports Illustrated put it, "Kinsella, the writer, has made up a story that in other hands might degenerate into foolishness, and made it work."

Shoeless Joe was the first of what would be several baseball novels and short stories Kinsella set in Iowa and Iowa City. His baseball writing includes novels The Iowa Baseball Confederacy, The Thrill of the Grass, Box Socials, and Butterfly Winter, and story collections such as The Dixon Cornbelt League and The Further Adventures of Slugger McBatt.

"Kinsella mythologized Iowa in a way that, if you travel abroad, that and Captain Kirk's birthplace seem to be the only kinds of literary facts people know about Iowa," says UI English professor Loren Glass. "He adopted not only Iowa, but Iowa's indigenous populations, as a way to tell stories about a region and state that have not commonly been the focus of literature."

In his City of Literature course, Glass teaches Kinsella's writing alongside other well-known authors who studied or taught in Iowa City, including Kurt Vonnegut and Lan Samantha Chang (93MFA), current director of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. "It's Kinsella's outlandishness, his playfulness, and his willingness to completely exceed the boundaries of time and space and readerly expectations that make his writing unique," says Glass.

While baseball was a favorite subject, Kinsella never considered himself a fanatic of the game. In a 1988 interview with The Daily Iowan, he described his books as "love stories that are peripherally about baseball." "I don't write play-by-play; I write about the emotion of people who are often only peripherally involved with the game," he told the student paper.

Even so, Kinsella is today considered one of his era's finest baseball writers and Shoeless Joe one of literature's great sports books. It was Hollywood, however, that would bring his magical vision of Americana to audiences worldwide and etch his name permanently on the game's cultural scorecard.

I don't have to tell you that the one constant through all the years has been baseball. America has been erased like a blackboard, only to be rebuilt and then erased again. But baseball has marked time while America rolled by like a procession o f steamrollers. —The character J.D. Salinger in Shoeless Joe

Filming for the big-screen adaptation of Shoeless Joe began in May 1988—a decade after Kinsella wrote his original short story—on a picturesque family farm owned by Don Lansing outside Dyersville. After years of wrangling between publishers and studios over the film rights, a screenplay penned by Phil Alden Robinson ultimately landed with Universal Pictures.

Robinson, a 35-year-old filmmaker who had just one previous directing credit, consulted Kinsella regularly during the writing process. While cuts and changes had to be made to the story, Kinsella felt Robinson's finished screenplay captured the essence of his novel. One of the biggest alterations was to the Salinger character, who because of legal concerns was renamed Terence Mann, a cloistered counterculture writer to be played by James Earl Jones. Kevin Costner (Ray Kinsella), Amy Madigan (Annie Kinsella), Ray Liotta (Joe Jackson), and Burt Lancaster (Dr. Archibald "Moonlight" Graham) also headlined the cast.

Kinsella returned to Iowa for the early days of production. In the movie's pivotal PTA scene, filmed inside a sweltering school gymnasium in the nearby town of Farley, Kinsella and his wife were in the audience of extras, though they never appeared in the film. The often-curmudgeonly writer found the moviemaking process tedious and after just a few days returned home to Canada. "The endless setups, the persnickety lighting, the repetitive retakes are not something I can tolerate," Kinsella wrote in a 2014 essay for ESPN.

Months later, after filming had wrapped, Robinson told Kinsella that they had at last settled upon a title: Field of Dreams. The name rang true with the author, who at one point had titled his novel Dreamfield, only to be overruled by his editor.

The movie opened on April 21, 1989, to rave reviews. Film critic Roger Ebert gave it four stars. "The director, Phil Alden Robinson, and the writer, W. P. Kinsella, are dealing with stuff that's close to the heart (it can't be a coincidence that the author and the hero have the same last name)," said Ebert in his review. "They love baseball, and they think it stands for an earlier, simpler time when professional sports were still games and not industries."

ILLUSTRATION: Tavis Coburn

ILLUSTRATION: Tavis Coburn

Unlike many authors whose books become unrecognizable on the big screen, Kinsella was thrilled with Robinson's interpretation. Kinsella, who had lost his father at a young age, was moved by the poignant scene when Ray meets his dad for a game of catch. "When he read the script, he started crying," Steele says. "And when he saw the premiere, he was sitting in the back of the theater and said, 'I can't believe it's my own words making me tear up.' I feel like if it makes the writer himself tear up, it's OK for us to cry too."

The book and film made Kinsella a sought-after name on the book-reading circuit, and over the years he returned to Iowa City regularly for lectures and to teach at the UI's Iowa Summer Writing Festival. Kinsella enjoyed taking his summer students on day trips to the movie site, where Lansing maintained the original field for the thousands of visitors who flocked to Dyersville from around the world each year. (The Lansing family sold the site in 2012 to an investment group called Go the Distance Baseball.)

Kinsella continued to write prolifically in the decade after the movie was released, but in 1997, his career was derailed by a freak accident. He and his fourth wife, Barbara Turner, were on a walk one night when he was struck by a car backing out of a driveway. Kinsella suffered acute head trauma, which affected his concentration and productivity as a writer.

In his later years, Kinsella took up competitive Scrabble, playing in tournaments around Canada and the U.S. But he also battled chronic kidney disease. While he continued to publish sporadically and travel for public readings, Kinsella never matched the success of Shoeless Joe and Field of Dreams.

"It was a novel and movie that was very special to him," Steele says. "He did tell me once that he wished he had written it later in his career. It was the first novel he'd ever written, and everything was compared to that. It's sort of like hitting a grand slam in your first at bat in the major leagues. How do you top that?"

In 2016, with his health and quality of life deteriorating rapidly, Kinsella died in Hope, British Columbia, using Canada's newly enacted doctor-assisted death legislation. He was 81.

Kinsella isn't around to see Major League Baseball's historic game on the field that first took shape in his imagination 40 years ago. Unlike the sentimental characters in Shoeless Joe, Bill was a pragmatist who likely would be more excited about the boost to book sales than any romanticized celebration of the game. But when the lights flicker on over the Iowa corn once more, and the ballplayers bound onto the field at dusk, he'd forgive us for imagining him sitting up in the stands next to his dad, talking about the Black Sox, and watching over it all with a smile.

After all, it's just the kind of scene W.P. Kinsella would have written.

FOR IOWANS, FIELD OF DREAMS IS MORE THAN JUST A MOVIE

In the final scene of Field of Dreams, as the film's score swells, the camera pans up from the diamond where Ray Kinsella and his dad are having a long overdue game of catch. The sweeping shot reveals a miles-long line of cars streaming to the farm at dusk.

Nic Ungs, the University of Iowa's director of baseball operations, was somewhere in that twinkling parade of headlights.

Ungs, a Dyersville, Iowa, native, was 9 when a local radio station put out the call for extras and their cars during filming in summer 1988. The day the memorable scene was filmed, Ungs' parents packed their baseball-loving son and his younger brother into their vehicle to join hundreds of other locals in the car line.

It was the start of Ungs' lifelong connection with the Field of Dreams—the classic film and the landmark movie site just outside of Dyersville that still attracts tourists from around the world. It's been more than 30 year since Ungs first watched the movie in Dyersville's one-screen theater, but the goosebump-inducing magic never seems to fade.

"To have a movie filmed in your hometown of 3,500 at the time, it was a big deal," recalls Ungs. "Everyone was eager to be a part of it."

This summer, Ungs plans to be one of the many Dyersville natives watching with pride when their hometown becomes the center of the real-life baseball world. Barring changes to Major League Baseball's calendar because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the league is set to host its first-ever game in Iowa at the movie site in August.

In 1990, a year after the film was released, Ungs was a batboy for a celebrity game at the Field of Dreams, where he was thrilled to meet baseball greats like Lou Brock and Reggie Jackson. After graduating from college in 2001 and being selected in the 12th round of the Major League Baseball draft, Ungs spent a short period of time traveling around the country for clinics and exhibitions as a member of the Field of Dreams' team of ghost players. Ungs also donned the throwback wool White Sox uniform in 2010 with the ghost team to re-enact scenes for an MLB Network documentary titled Triumph and Tragedy: The 1919 Chicago White Sox.

Ungs was a star baseball player at Dyersville Beckman and the University of Northern Iowa before enjoying an 11-year pitching career in the minor leagues and overseas. A former member of the U.S. Olympic Team, he returned to Iowa three years ago to run the day-to-day operations of the Hawkeye baseball team.

"I moved away from Iowa, but it always kept me close because guys would say, 'Oh yeah, I know where that is because of Field of Dreams,'" Ungs says. "It was great to have that tie back to where you're from. Even though you see it a thousand times, it always felt very special. I'm glad we still have the location."

Ungs isn't the only Hawkeye with a deep affection for the movie. Iowa baseball coach Rick Heller was coaching at Upper Iowa University in Fayette, not far from Dyersville, when the movie was released in 1989. Heller's teams would stop their bus at the Field of Dreams each year to throw the ball around and soak in the idyllic scene.

"I have fond memories of what the Field of Dreams represents for Iowa," says Heller, who grew up in Eldon in southeast Iowa. "It's about the dream, the love of the game, and father-son relationships."

Heller says the nostalgic film reflects Iowa's rich baseball heritage, particularly in many small towns where the game is a way of life. A number of the game's stars of yesteryear grew up playing on rural ballfields like the diamond idealized in the movie. Hall of Famers Bob Feller of Van Meter and Red Faber of Cascade, and former UI stars Mike Boddicker of Norway and Cal Eldred of Urbana, are just a few of Iowa's many homegrown baseball legends.

"The game is something they grew up with and is passed down from their grandparents and parents," Heller says. "It's not as big as it used to be, I'm sad to say, but it's still there. ... It's a part of their culture and part of life."

Iowa softball coach Renee Gillispie, a Danville, Iowa, native, still screens Field of Dreams for her teams each year on bus trips. "To hear, 'Is this heaven? No, it's Iowa,' was the coolest thing for an Iowa kid," says Gillispie, who was just beginning her coaching career when the movie was released. "It seemed like the first time Iowa was ever mentioned in a movie, besides Radar from M*A*S*H being from Ottumwa. It was a big deal to see Iowa on the big screen."

Gillispie says the Hawkeyes have had ongoing talks with Upper Iowa University about playing a fall softball game at the Field of Dreams. While the two programs couldn't get the contract finalized in time last year, she's hopeful that will come together this fall.

For Ungs, he's looking forward to Major League Baseball's showcase of the place that means so much to him. "It's been a pretty big part of my life, and it keeps Iowa on the map. We're not just the state with the caucuses."