Old Gold: Duke Slater the Hawkeye Trailblazer

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

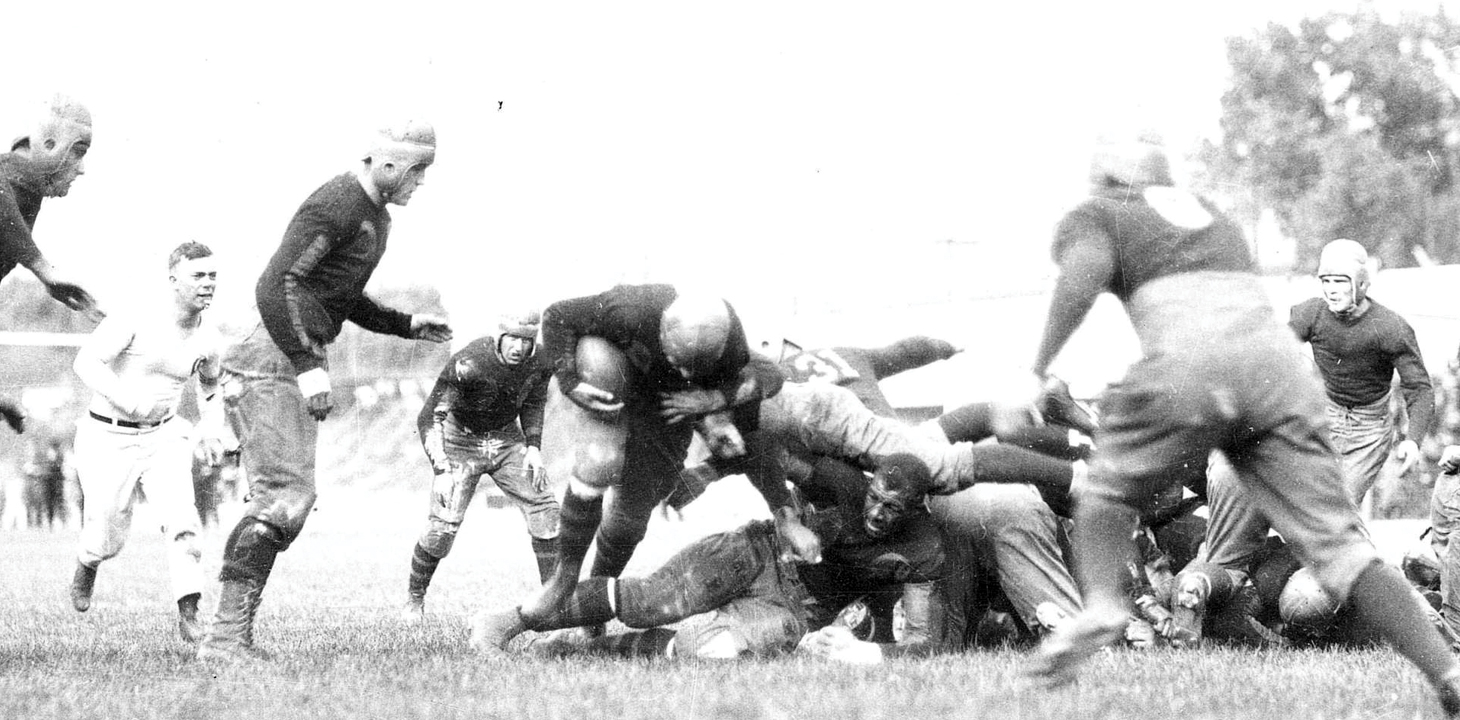

A helmetless Duke Slater

(at the bottom of the pile)

makes a block in Iowa's

10-7 home victory over

Notre Dame in October

1921. Iowa earned a perfect

7-0 record that year to

become one of the greatest

teams in Hawkeye history.

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

A helmetless Duke Slater

(at the bottom of the pile)

makes a block in Iowa's

10-7 home victory over

Notre Dame in October

1921. Iowa earned a perfect

7-0 record that year to

become one of the greatest

teams in Hawkeye history.

A century has passed since Frederick Wayman "Duke" Slater (28LLB) received his first national honors as an offensive tackle for Iowa's football team. A sophomore during the 1919-20 season, Slater's best years were yet to come, culminating as a senior when he led the Hawkeyes to the Big Ten title in 1921, their first in over two decades. Following that 7-0 season he was named a first-team All-American.

Slater's many honors include election to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951, the year of its opening. In 1972, the UI renamed a dormitory in his honor. This fall, a bronze-relief sculpture featuring Slater was unveiled as part of the renovations to the north stands at Kinnick Stadium, further ensuring his memory.

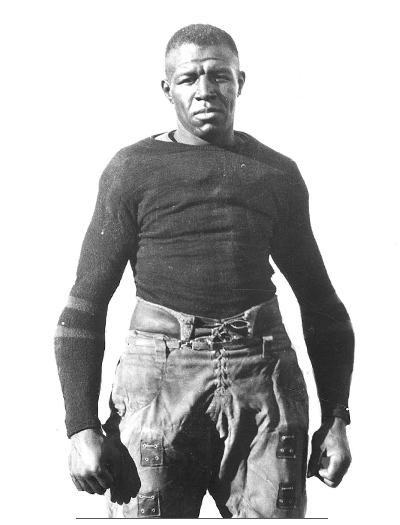

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Frederick Wayman "Duke" Slater

PHOTO: FREDERICK W. KENT COLLECTION, UI LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Frederick Wayman "Duke" Slater

Historian Richard Breaux (98MA, 03PhD)—writing in former UI faculty members Lena M. Hill and Michael D. Hill's excellent book, Invisible Hawkeyes (University of Iowa Press, 2016)—noted that Slater and other African American athletes at Iowa during the early 20th century experienced the cruel paradox of adulation and discrimination. While achieving fame for his outstanding athleticism on the field, Slater—like other black students—was not permitted to live in university housing and was subject to other forms of racism during his academic career in Iowa City. The university's catalog, policy handbook, and housing rules did not explicitly exclude students, faculty, and staff on account of race. However, during the early to mid-20th century, unwritten and long-enshrined discriminatory customs and practices were enforced.

In 1919, it was believed that there were perhaps 50 African American students enrolled at Iowa, accounting for about 1% of the overwhelmingly white campus' population at the time. Though a Midwesterner—born in 1898 in Normal, Illinois, and a graduate of Clinton, Iowa, High School—Slater no doubt experienced the paradox of fame and scorn. Despite such barriers, Slater recognized opportunities at Iowa for prospective students and helped recruit other black athletes. His legacy reached into mid-century, more than 30 years after he graduated, when in 1955 five black players started for Iowa under Coach Forest Evashevski, a number possibly unequaled in the Big Ten at the time.

Following graduation in 1922, Slater played professional football for 10 seasons with teams in Milwaukee; Rock Island, Illinois; and Chicago. During the offseason for several years in the 1920s, he returned to Iowa City to study law, and in 1928 earned a Bachelor of Laws degree. He settled in Chicago, becoming an assistant district attorney and, in 1948, was elected as a judge to the city's municipal court. He became the first black judge to serve on the Superior Court of Chicago in 1960, and four years later joined the newly formed Circuit Court of Cook County. He died in 1966.

A dedicated team player and coach. An attorney and jurist. The new sculpture at Kinnick Stadium is a fitting tribute to an alumnus whose legacy remains steadfast today.