A Play On Words

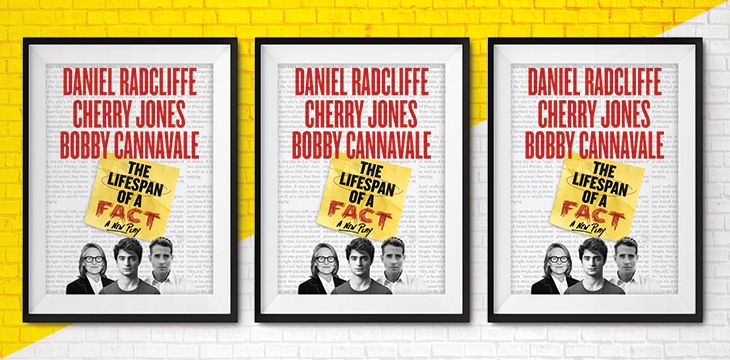

POSTER: POLK & CO

POSTER: POLK & CO

John D'Agata calls it the most nerve-wracking walk of his life.

Last fall, the author and director of the UI Nonfiction Writing Program left his New York City hotel and headed to a nearby rehearsal hall. D'Agata was attending the first table reading of a new Broadway play, The Lifespan of a Fact, based on his book of the same name and starring Daniel Radcliffe. Terrified of how he'd be portrayed in the script, D'Agata braced for the worst.

John D'Agata

John D'Agata

When he and co-author Jim Fingal released their book five years earlier, its reception was, “suffice it to say, challenging,” as D'Agata puts it. The book was intended as farce—an over-the-top recounting of how D'Agata and his fact-checker, Fingal, butted heads for years over a magazine article and, ultimately, the complicated nature of truth. Some got it. (Slate put it among its 10 best books of 2012.) Others didn't. (The New York Times called D'Agata “a wolf in journalist's clothing.”) Where D'Agata had aimed for humor in his antagonistic back-and-forths with Fingal, some read it as an actual account of their fact-checking process. He worried that on stage, the D'Agata character would be the incorrigible villain.

Instead, watching the first read-through of the script that day, D'Agata found that the adaptation masterfully captured the central question of the book: whether a literary essayist should be granted leeway with the facts to achieve a greater truth through his storytelling. “The great thing about the play is that it's funny, frustrating, and tender all at once, and so are all of its characters,” D'Agata says. “At various points during the show you find yourself agreeing and disagreeing with everyone in it, even though its characters spend the play arguing with each other. So no one comes out of it looking heroic or villainous. They look human.”

The Lifespan of a Fact opened Sept. 20 at Broadway's Studio 54 for a 16-week limited run. Two-time Tony nominee Bobby Cannavale plays D'Agata, while Radcliffe, of Harry Potter fame, plays Fingal. D'Agata doesn't have a formal role in the production—a team of Broadway playwrights adapted the book for stage—but he read drafts of the script and offered occasional feedback during its development.

“Years ago David Foster Wallace gave me advice about this kind of stuff. He said that if you trust the people who want to adapt something of yours, and they have a good track record, then just sign what you have to sign and walk away,” D'Agata says. “Leave the moviemaking, or in this case the theater-making, to the experts.”

The book's path to the theater began at a speaking appearance by D'Agata several years ago. After the bookstore reading in Manhattan, a Hollywood producer who'd recently begun working on Broadway introduced himself to D'Agata. The producer, Norman Twain, said the book would make for a great play. Still a bit numb from the literary firestorm swirling around the book, D'Agata politely thanked him and moved along. But the next day, Twain tracked down D'Agata's agent, and within a month, they had a contract.

Twain, best known for producing the film Lean on Me, died in 2016, but not before he and D'Agata became good friends. “Amid all the nutty hysteria that the book attracted, he managed to see something in it that no one else did,” D'Agata says. “He saw a story about how very difficult the truth can be.”