PHOTO: 1966 Hawkeye yearbook

PHOTO: 1966 Hawkeye yearbook

Lt. Col. Zachary Buettner inherited a century and a half of history when he returned to South Quad last year to lead the University of Iowa's Army Reserve Officers' Training Corps.

To step back in time, he need only visit the meeting room lined with old photographs, including a portrait of Lt. Alexander D. Schenck, who founded the university's military department in the 1870s. Or pluck a volume from the shelf of dusty yearbooks chronicling the military balls, Scottish Highlander band performances, and Governor's Day celebrations of decades past. Or spin the leather football from the annual CyHawk game ball run, a relay between UI and Iowa State cadets that has been a tradition since the 1980s.

Or he might pick up the brick.

On a recent afternoon, Buettner hefts the cement block up close to read the inscription: "May 5, 1970," the date a Vietnam War protestor lobbed the brick through the window of the ROTC's old quarters at the Field House. Passed down the line of department commanders in the decades since, the relic sits near Buettner's desk as a quiet reminder of one the most turbulent times in the history of the ROTC.

This year, the Army ROTC celebrates its 100th anniversary on campuses around the country. That includes Iowa City, where the UI's Mighty Hawkeye Battalion has roots that stretch well beyond a century. The battalion has been a university mainstay since its founding in the years after the Civil War—spanning the world wars of the 20th century, the contentious Vietnam era, and the modern-day wars in the Middle East.

The times have changed, but the ROTC's core mission has not.

"We build future leaders for the Army and the civilian world," says Buettner, 97BBA, whose military career came full circle in 2015 when he was tapped as the UI's 52nd professor of military science.

"I like to think that our cadets go out into the world, and wherever they go, they take that with them and make it a better place."

TWO CANNONS AND A MARCHING BAND

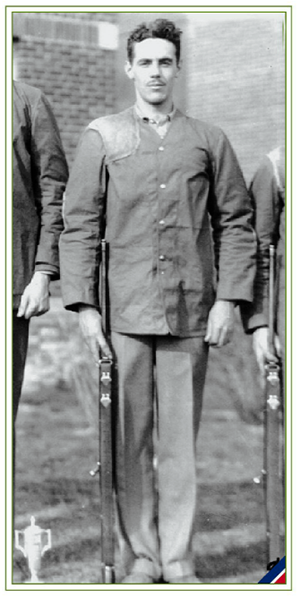

SUI ROTC RIFLE TEAM MEMBER, 1930.

SUI ROTC RIFLE TEAM MEMBER, 1930.A year before the U.S.'s entrance into World War I, President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Defense Act of 1916 and created the ROTC as it exists today. More than 1,000 universities and colleges now train officers through ROTC programs, including Iowa's three Regent universities. In exchange for merit-based scholarships, which can cover as much as the full cost of tuition, ROTC cadets are obligated to serve for eight years, including three or four years active duty.

The War Department formally established the State University of Iowa's ROTC infantry unit in 1917, but the beginning of the university's military instruction dates to 1864-65, at the tail end of the Civil War, when the UI offered a course titled "Gymnastics and Military Drill."

Schenck organized the UI's Military Department in earnest in 1874 when he secured two cannons, muskets, and munitions for 138 men, who drilled on the sloping west lawn of the Pentacrest. Soon, the university's first military marching band began rehearsal. In those early years, military classes were held largely in the Old Capitol and other buildings in the Pentacrest until an armory was constructed in 1904 near the future site of the Main Library.

At the turn of the 20th century, it wouldn't have been out of place to hear munitions echo in the countryside during sham battles outside Iowa City. The old yearbooks on South Quad's shelves detail the so-called "Battle of Mehaffey Bridge," in which a snowstorm tested the cadets' endurance. A mock skirmish at Cou Falls Bridge in northern Johnson County had men toting 10,000 rounds of ammunition to the battlegrounds. In 1910, the "Attack on the Stronghold of West Liberty" saw the entire battalion marching out of Iowa City to lay siege to the neighboring town.

The UI's ROTC underwent rapid expansion in the years after World War I, growing from 400 men in 1917 to more than 1,347 participants by 1924. The battalion boasted one of the nation's top rifle teams in the 1920s, and in 1936, Col. George Dailey organized an accompanying bagpipe band that would come to be known as the Scottish Highlanders. The kilted musicians became a fixture at Hawkeye football games and parades for decades, and the Highlanders earned national renown as the largest bagpipe band in the U.S.

After Pearl Harbor, the hard realities of World War II hit home. Men were scarce on campus as soldiers shipped out for Europe and the South Pacific. Fraternities disbanded and the houses were used for military training programs. The Scottish Highlanders, which saw 71 of its 75 male members called to war, transitioned to an all-female group. And the ROTC as a whole dwindled from about 1,600 members before the war to about 200 in 1945.

UNDER FIRE AT HOME

As the nation exhaled in the years after the Allies declared victory, normalcy returned to campus. A military affairs committee formed to handle the great number of returning war veterans. The temporarily suspended military ball resumed in 1947, and more than 1,500 students attended. In the era of relative peace to follow—though interrupted by the Korean War—the ROTC transitioned from a mandatory program to fully voluntary for male students. A few years after that landmark change in 1963, less than 600 men were enrolled in ROTC.

The national unity that thrived in a prosperous post-war America, however, wouldn't last. In the 1960s, as the decade of social upheaval wore on and the nation sunk into the Vietnam quagmire, anti-ROTC sentiments flared. The future of the UI's military department became clouded in the spring of 1970, when protests reached a crescendo and the faculty and student senates voted to abolish the ROTC.

The draft, the unpopular and deadly war, and the ripples from Kent State all came to head in the first week of May 1970 in Iowa City. About 400 protestors stormed an awards ceremony for cadets at the newly built Recreation Center, forcing its cancellation. At a protest on the steps of the Old Capitol, students spray-painted R-O-T-C on the building's four columns (see above). Some smashed windows at the National Guard Armory and downtown businesses, while others closed intersections with sit-ins and clashed with authorities in full riot gear.

While the protests of that era have been well-chronicled, the perspective of those in uniform on campus is a story less told. John Kundel, 69BA, 74MA, still feels the sting of anti-ROTC sentiments. Protestors hurled garbage at him when he marched in the Homecoming parade, and he still gets choked up talking about the poor treatment he and other veterans received after coming home from Vietnam.

"Many [anti-war] students and non-students took out their anger against the government on us," says Kundel, who went on to to serve 18 years in the Army Reserve and retired as a major. "That was a hard pill to swallow. While I certainly wasn't wise back then, I knew the protestors were really expressing anti-government feelings rather than being against us. But it still hurt."

OFFICERS IN TRAINING

In some ways, the ROTC of decades past looks a lot like the ROTC of today, an era defined by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Cadets wake bright and early for physical training with daily runs and workouts around campus. They participate in weekly field exercises at the UI Ashton Cross Country Course or local parks, where they drill in tactical scenarios—not unlike those sham battles of the early 1900s.

At the same time, much has changed. The ROTC became more inclusive in 1972, when the military lifted the restrictions prohibiting the full participation of women. The program is now more standardized across all colleges and universities compared to previous eras, when the individual professors of military science largely set the curriculum. Today's cadets also leave with a greater cultural perspective, with many taking part in a three-week immersion program overseas.

"It's about more than tactical proficiency, it's about more than marching, it's about more than shooting," Buettner says. "It's about understanding other cultures and respecting other cultures. I think what we figured out in Iraq and Afghanistan is those leaders who understood different perspectives were much more successful."

In recent decades, the ROTC has traded the quarters of the Old Armory and Field House for South Quad, which was built by the Navy during World War II as a pre-flight training facility. Inside, you'll find cadets like Michael Whetstone, a senior physics major and member of the Iowa National Guard who was one of 17 fourth-years to take the oath of office in a May ceremony. All told, about 110 students this past year took classes through the Army ROTC, and about 50—including 11 women—have committed to the officer training program.

"I'm done working out, have already had a class, and eaten breakfast—and it's only eight-thirty."

- Michael Whetstone

Whetstone, who this past spring was among a handful of outstanding cadets to receive the prestigious Governor's Award in Des Moines, said the discipline and leadership skills he's developed in ROTC have helped him succeed in all areas of his studies. Says Whetstone of his typical schedule: "I'm done working out, have already had a class, and eaten breakfast—and it's only eight-thirty."

Students can take ROTC classes for up to two years with no military obligation. Those awarded an ROTC scholarship go on to be commissioned as second lieutenants in the Army after graduation, though some can enter the National Guard or Army Reserve while pursuing a civilian career.

The battalion has produced countless alumni who have become accomplished leaders beyond the military. Arthur McGiverin, 51BSC, 56JD, received training as an Army officer at UI and served during the Korean War before he rose to the top of Iowa's courts system. McGiverin sat on the Iowa Supreme Court for 22 years, including 13 years as chief justice, before he retired in 2000. In June, he was inducted as an inaugural member of the Army ROTC National Hall of Fame.

"It helped me learn to get the facts, then be decisive," says McGiverin of his days in the ROTC in the 1950s. "In the Army, you determine all the facts before attacking an objective, determine what your options are, then do it."

CARRYING THE TRADITION

It's mid-spring, just a few weeks before their end-of-semester commissioning ceremony, and ROTC students are limbering up outside the Field House for a sunrise run.

Whetstone and other seniors lead the Army cadets for the annual workout with the UI's Air Force ROTC and Marine Corps Officer Candidate School members. At 0615, they set out toward the heart of campus. Four neat columns about 20 deep, trailing their unit's flags and a UI Police SUV, trot down Burlington Street, then Clinton Street.

Their destination on this bright morning—the Old Capitol, where they stop for a group photo—is a fitting one. Countless ROTC classes have posed under the golden dome over the decades. Swap out the Fitbits and neon running shoes for button-down coats and polished boots, and it could be a scene from any UI era.

For Whetstone, it's his last joint run before he takes his oath of office. He hopes to one day teach high school science while he serves in the National Guard. But for now, like so many who have come before him, he's savoring his final days with the Mighty Hawkeye Battalion.

Photos courtesy the Fred W. Kent Collection, Special Collections, UI Libraries; and the UI Army ROTC.

Mighty Hawkeye Battalion Alumni Group Takes Shape

When Robert Hedgepeth looks back on his days in Iowa City, some of his fondest memories are of the ROTC.

Rappelling at the Field House, training near Coralville Lake, and serving in the Homecoming color guard are among the moments that still strike a nostalgic chord.

"It's a home for me back on campus," says Hedgepeth, 89BSE, a colonel with the National Guard approaching his 30th year of military service.

That's why Hedgepeth is working to build the Mighty Hawkeye Battalion Alumni Association, which keeps former ROTC cadets connected to today's UI military department. Among its many aims, the MHBAA provides current cadets and recently commisioned officers with mentorship opportunities while promoting the department and its recruiting efforts.

"We'd like to hear more stories from others and find ways for those people to help the department and the current corps of cadets in producing leaders for tomorrow's Army," says Hedgepeth, an electrical engineer in Johnston, Iowa, and president of the MHBAA board.

The MHBAA is open to all alumni who participated in the Army ROTC. To connect, email HawkeyeBnAlum@gmail.com or search for the Mighty Hawkeye Battalion Army ROTC on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Photos courtesy the Fred W. Kent Collection, Special Collections, UI Libraries; and the UI Army ROTC.

EXTRA CONTENT! To view more photos UI ROTC over the past 100 years, visit the UIAA Facebook gallery.

The ROTC at UI: A Timeline

1861

Civil War breaks out; Lincoln issues a call for volunteers to fight in the northern armies. Of the 177 men attending the State University of Iowa, 124 laid down their books to fight. A military department is established at the university, though it will be several years before it takes hold.

1864-65

The university offers its first military course, "Gymnastics and Military Drill," which, according to the course catalogue, was designed to "give special attention to the development of a healthy, vigorous, symmetrical physique."

1874

A well-organized military department is initiated, with First Lt. Alexander D. Schenck leading the first SUI Battalion. Schenck is the university's first professor of military science and tactics.

1880s

The university holds its first Battalion Day, which later became the annual Governor's Day.

1881

First Lt. George A. Thurston establishes the University Band, which provided music for parades

and other events.

1890s

A rifle range is built and the university fields its first rifle team, which finishes third in a contest with nine other military schools.

1895

The first military ball is held.

1916

Congress passes the National Defense Act of 1916, signed by President Woodrow Wilson. The bill, in part, establishes the Reserve Officers Training Corps to standardize military instruction at various colleges and universities.

1917

The War Department establishes an ROTC infantry unit at the State University of Iowa, with the federal government providing $45,000 worth of equipment, as well as uniforms.

1920

An engineering unit is established at the university. Students in the program take basic ROTC classes, along with rigging, mapmaking, military bridging, and demolitions.

1927

The newly built Iowa Memorial Union is dedicated at the military ball, which 600 couples attended.

1936

A bagpipe band called the Scottish Highlanders forms to accompany the ROTC. It makes its first formal appearances the following year at the military ball and a Hawkeye football game.

1942

An accelerated ROTC program and accelerated university program are introduced with the onset of the U.S.'s involvement in World War II. No advanced ROTC courses are offered. By 1944, only one company—a medical group—is left on campus.

1943

All ROTC Advanced Corps students are called to active duty amid the Second World War.

1947

The military ball, which had been cancelled during the war years, returns to campus with more than 1,500 students attending.

1948

The first Air Force ROTC class graduates from the university, with 25 men receiving commissions.

1960s

The Guidon Society, a women's auxiliary to the ROTC, is organized. The group serves as hostesses for ROTC and UI activities, takes part in service projects, and provides moral support to the brigade.

1961

The university adopts a trial program requiring just one year of ROTC for all eligible male students as a prerequisite for graduation. Prior to that, the first two years were mandatory.

1963

The Board of Regents passes a resolution making ROTC entirely voluntary. In its place, a mandatory four-hour orientation is established for incoming students.

1964

The ROTC Revitalization Act institutes two-year and four-year scholarship programs.

1970

Anti-ROTC sentiments amid the Vietnam War resulted in protests and outbreaks of violence on campus. The Faculty Senate and Student Senate voted to abolish the ROTC at the UI. Anti-ROTC students attempted to take freshman ROTC courses in an attempt to disrupt classes.

1972

Women are allowed to participate fully in the ROTC for the first time.

1985

The Old Armory, which was built in 1904 near the Main Library on the west side of the river, is razed.

1987

Members of the UI and Iowa State University's ROTC conduct their first game ball run—an annual tradition carrying a football from Ames to Iowa City and vice versa ahead of the rivalry game.

2016

Cadets mark the 100th anniversary of the formation of the ROTC nationally with a rappelling demonstration from the rafters of Carver-Hawkeye Arena during a wrestling meet.