In the 1980s, the international antiapartheid campaign's demand echoed around the world. And on Feb. 11, 1990, when the South African activist finally walked out of a prison near Cape Town after 27 years of imprisonment, the stunning impact of the historic moment resonated all the way to Iowa City.

As news spread of Mandela's release, some 300 students and residents sang and danced through the streets in a spontaneous, joyful parade from the Pedestrian Mall to Old Brick. A local TV reporter stopped one of the marchers, a black South African student, and asked how she felt. Zodwa Dlamini couldn't conceal her elation. "The very fact that I saw that man getting free, it was like myself being free," she said. "For the first time in my life, I've felt the dignity that I've never had."

In the 1980s and 1990s, hundreds of black South African students attended U.S. universities on scholarships that aimed to prepare them to be leaders of government, business, and education in their nation when apartheid fell. At the University of Iowa, the Southern African Scholarship Program set up by former president James Freedman paid students' tuition if an international sponsoring agency met their living expenses. Among those students were Dlamini and Zukiswa "Zuki" Cindi, who shared an apartment in Iowa City in the late '80s.

At that time, a civil war raged in South Africa. In 1985, in response to a rising tide of protest against apartheid—the institutionalized racism that relegated blacks to a separate and inferior state of "apartness"—the government had imposed a state of emergency. While the two women grew up in different parts of South Africa—Dlamini in the rural Free State province in the heart of the country and Cindi in the Eastern State—both had experienced the soul-crushing cruelty and injustice of apartheid. As Cindi wrote in an essay for a UI rhetoric class, life in South Africa for blacks was "probably worse than hell."

Developed after World War II, apartheid set up a system of racial segregation for South Africa's main population groups: whites, Indians, coloreds, and blacks. Apartheid denied blacks South African citizenship, voting rights, a decent education, good medical care, and every other vestige of equal participation in their country's life. It affected every area of their existence, from whom they could marry (interracial unions were banned) to where they could live—millions of blacks were forcibly removed from their homes and relocated to ten "homelands" in areas with few economic resources. In addition, blacks were unable to own businesses or practice a profession in areas designated for whites, and they were frequently paid less for doing the same job as whites. They had to carry identity cards specifying their official racial category, and, without a special pass giving them permission to be in a white area, they risked arrest and fines, imprisonment, or deportation to their homeland.

Other rules and social mores inflicted psychological wounds. As Cindi explained in her rhetoric essay, "A black woman, no matter her name or age, would usually be referred to as 'Jane' or 'girl.' The man was 'Jim' or 'boy' and the whites were always 'Master' or 'Madam.' Even a white girl of three years was 'Madam' to a 60-year-old 'girl.'"

Left: Zukiswa "Zuki" Right: CindiZodwa Dlamini

Left: Zukiswa "Zuki" Right: CindiZodwa Dlamini

Dlamini's parents were teachers who impressed upon her that education was the key to escaping what she calls "the clutches of apartheid." So, in 1985, at the age of 28, she came to the UI to work on a master's degree in geography. She already had a bachelor's degree from the University of Zululand and an honors degree from Fort Hare, the country's oldest and most prestigious university for blacks, which Nelson Mandela had also attended.

Although geographically similar to the agricultural Free State, Iowa differed in one critical respect. "There were very few black people in Iowa at the time," recalls Dlamini. "And yet, oddly enough, Iowa was the one place where I felt like a human being. I was treated just like everybody else."

Cindi arrived at the UI in 1986 at age 27 to study for an undergraduate degree in business, after fighting to gain an education at home. Since schooling for blacks in her hometown of Cradock only went to grade 10, she had to go to live with her uncle while she finished high school near Johannesburg, 500 miles away. Her first year there, in 1976, coincided with one of the most infamous and deadly anti-apartheid protests.

In a sprawling black township outside of Johannesburg, in what became known as the Soweto Uprising, police shot and killed more than 170 students who were protesting being taught in Afrikaans—the language of their oppressors, the white minority who led the country. Following the massacre, black students nationwide demonstrated against apartheid and refused to go to class.

"You didn't know whether to go to school or not, but you wanted to be part of what was happening," Cindi says. "You knew that you might die tomorrow."

After graduation, Cindi enrolled at Fort Hare, where further clashes erupted between students and police. Eventually, she and others were expelled for protesting the racism of the white administration.

Both Dlamini and Cindi had been schooled in the Bantu Education system, a segregated and intentionally inferior form of education for blacks. Hendrik Verwoerd, South African prime minister from 1958 to 1966 and the architect of apartheid, once famously said that "there is no place [for blacks in society] above the level of certain forms of labor."

As a result of the poor education system in South Africa, both women had to work hard in Iowa to make up their academic deficit. Cindi would study in the evenings until bedtime, then wake up in the middle of the night to squeeze in a few more hours with her books before falling asleep again. Both women worked part-time, Dlamini in the UI Office of Affirmative Action and Cindi at UI Hospitals and Clinics. They also cleaned houses, just as many black women do in South Africa.

But, life in Iowa wasn't all work and no play. The women held lively parties at their Oakcrest Street apartment, where singing and dancing went on until the early hours of the morning. One night, a special guest joined them: the famous South African jazz trumpeter, Hugh Masekela, fresh from a concert at Hancher.

Explains Cindi, "We are a kind of people who, whether we're sad or happy, we sing."

That passion found a practical purpose when Cindi finished her bachelor's degree. She wanted to enter Iowa's M.B.A. program, but her scholarship had run out. Fortunately, a group of Iowa City residents had formed Iowa South African Scholarship Incorporated (ISASI), raising money through garage sales and pancake breakfasts. South African students did much of the fundraising in a way they knew best.

Cindi, Dlamini, and four other South Africans formed Imilonji, which means "sweet music" in Xhosa. The group performed on campus, at the VA hospital, in area churches, and at South African student events, such as the annual commemoration of the Soweto Uprising. Their songs in Zulu and Xhosa were a lively mix of sharply worded antiapartheid protest songs, Christian hymns, and traditional songs about life events such as births and weddings. In one deceptively melodic song, "Senzeni Na," they sang: "What have we done? Our sin is our Blackness. The Boers [Afrikaners] are dogs, and they shall die like dogs."

The group recorded and sold a cassette tape titled after the South African freedom cry, "Amandla Ngawethu!—Power to the People." It concludes with the poignant pan-African anthem "Nkosi Sikelel' Afrika" ("God Bless Africa.")

With the help of an ISASI scholarship, Cindi earned her M.B.A. and returned to South Africa in 1990. Dlamini followed her two years later, after receiving her Ph.D. in education and writing her dissertation on the education of South Africa's homeless children.

They came home to a country on the cusp of great change. Although violence still flared regularly between political factions and different tribes, the state of emergency had been lifted and the legal apparatus of apartheid was being dismantled. For their parts in this historic effort, Mandela and South African President F.W. de Klerk would receive the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize.

The two women immediately sought to contribute to their new nation. Dlamini—a forthright Zulu who isn't afraid to speak her mind—talked her way into a teaching job after confronting a white administrator at the Johannesburg College of Education about the lack of black professionals.

Cindi provided education and skills training to the youth in her hometown, which had endured much during apartheid. In 1986, four young male anti-apartheid leaders, now known as the Cradock 4, had been kidnapped by the security police, driven to a field, and summarily executed, their bodies burned to hide evidence. In the context of those sacrifices, Cindi reminded her students "not to lose hope and to remember where you come from."

Then, on April 27, 1994, the two women participated in South Africa's first non-racial democratic election. Cindi voted for the first time in her hometown, where people lined up from early in the morning. She says, "It was the best moment of my life."

Dlamini recalls a day of tumultuous emotions, with elation tempered by sadness. "I thought about those who had paid the ultimate price for us to be able to vote," she says. "They voted with their blood."

Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress, long considered "terrorist" enemies of the apartheid state, won a landslide victory. On May 10, Mandela took the oath of office as the nation's first black president. Standing before thousands of people gathered on the lawn beneath the Union Buildings in Pretoria, Mandela promised a new beginning: "We enter into a covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world."

Indeed, the first years in the new South Africa were exciting for Dlamini and Cindi, who—thanks to the confidence and knowledge provided by their Iowa education and experiences—moved up through ever more prestigious jobs. Eventually, both women accepted positions in the new provincial governments: Dlamini became head of the Northern Cape Province Education Department, while Cindi headed the Eastern Cape Department of Arts and Culture. After about two years, though, they left because of conflicts with their superiors, who were political appointees. Ironically, the quality of their UI education proved to be part of the problem. Cindi recalls, "People used to say, 'Sho! You think you know everything!'"

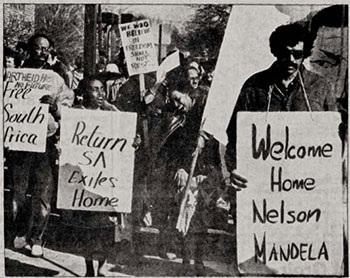

In this Daily Iowan photo from 1990, UI community members gather in downtown Iowa City to celebrate Nelson Mandela's release from prison.

In this Daily Iowan photo from 1990, UI community members gather in downtown Iowa City to celebrate Nelson Mandela's release from prison.

The women were victims of a larger problem emerging in South Africa—the lack of skilled officials in local and provincial government. The brightness of the "Rainbow Nation" began to fade in other ways, too. The Mandela administration provided much-needed basic services such as new homes, electrification, and clean running water to millions stuck in poverty. In addition, access to education improved, to the point that almost 90 percent of eligible students are now enrolled in high school compared to about 50 percent in 1994. Yet, many social ills proved difficult to overcome.

Today, South Africa is ranked by the World Bank as one of the most economically unequal nations in the world, with enormous income disparities between blacks and whites. The bank's South Africa director said, "In large part, this is an enduring legacy of the apartheid system, which denies black people...the chance to accumulate capital in any form—land, finance, skills, or social networks."

Unemployment also remains at record highs of 25-30 percent, political corruption is rampant, and violent crime is widespread, with 19,000 murders and 50,000 rapes reported annually. The recent trial of Oscar Pistorius highlighted the enormity of domestic violence, with "intimate femicide"—the murder of a woman by her partner—now the country's leading cause of unnatural death for women.

Plus, the nation has struggled against its biggest challenge since apartheid: HIV/AIDS. Thabo Mbeki, who succeeded Mandela as president in 1999 and refused to believe that HIV caused AIDS, impeded the delivery of life-saving anti-retroviral drugs. By the time drugs were made available in 2003, an estimated 365,000 people had unnecessarily died of AIDS. Today, while AIDS is not the killer it was 10 years ago, some 5.7 million people of South Africa's 50 million are HIV positive.

The unsettled state of the nation can be seen in the different trajectories that Dlamini and Cindi's lives have taken in recent years. Dlamini was able to rebound from her short tenure in provincial government, first by starting her own consulting company, which assisted governmental agencies in education, rural development, and legal reform, as well as land claims by blacks whose property had been taken by whites. Then, in 2005, she became South Africa's chief delegate to the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, a major infrastructure initiative in which South Africa gets much-needed water from the neighboring Kingdom of Lesotho through a series of dams, tunnels, and reservoirs.

But, Cindi's life reflects the hardships that still afflict many South Africans. After the deaths in quick succession of her sister, her priest, and her foster daughter, she fell into a deep depression and was eventually hospitalized. She endured several difficult years, only recently securing short-lived temporary work, and her financial situation remains precarious.

"The very fact that I saw [Mandela] getting free, it was like myself being free. For the first time in my life, I've felt the dignity that I've never had."

~Zodwa Dlamini

Still, she has no regrets about returning home, where her UI education allowed her to give back to those in her country less fortunate. Dlamini is also proud of her decision to join South Africa's nation-builders. She recognizes many challenges ahead but points to major strides made, saying, "Twenty years cannot be compared with 400 years of oppression."

Above all, both women are heartened by the sheer dignity that has been restored to millions of black South Africans. That dignity reignited hope, which illuminates the darkest days. The words that Cindi wrote almost 30 years ago in her UI rhetoric essay remain true today:

"I perceive some changes coming through in South Africa. Whether for better or worse, I cannot say. But I believe that a person should prepare him or herself for those times. Indeed, it is proper for one to be always optimistic for the future."

Martin Klammer, 89MA, 91PhD, is a professor of English and Africana Studies and the writing director at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa.