Weeks of isolation and torment render the last few days of the school year near unbearable for 13-year-old Gracie Schulte. The sparkling show choir star, once accepted at a table of fellow singers she thought were her friends, can no longer face the cafeteria. On this lowest of days, Gracie seeks refuge in the girls' bathroom of her Cedar Rapids, Iowa, junior high, tearfully eating among the toilets and paper towels.

Earlier that spring, Gracie had lost the loyalties of a girl she considered her best friend. Jealousy and misunderstanding over the choreography of a dance program had downspiraled into social ostracism. Gracie's friend stopped speaking to her and two other close choir peers turned against her with verbal, sometimes physical, insults. Bewildered, Gracie did her best to make it through the school hours before coming home upset and confused.

For a while, Gracie's parents, Mike and Mary Pat, stayed out of the situation. Knowing adolescent friendships can bring drama and conflict, they wanted to see if the kids could work it out. Then, one evening, a rapid-fire barrage of text messages appeared on Gracie's phone:

- "You can rot in hell."

- "We know the devil inside of you."

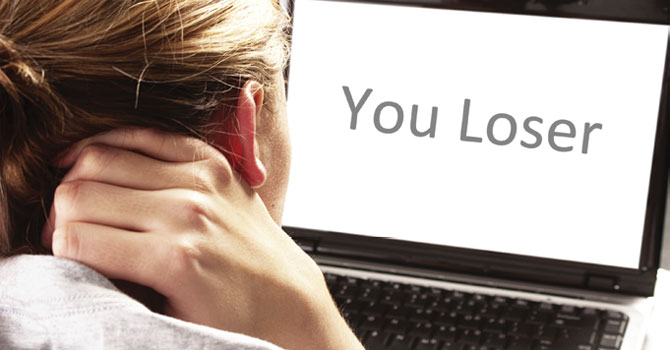

The harsh words prompted Mike to text back, firmly telling the person on the other end not to speak to his daughter that way. But when the false Instagram account created under Gracie's name appeared online, the harassment moved to a whole new level. The fake account featured her photo and bio—and humiliating, derogatory messages: Gracie Schulte is a whore.

Gracie's experiences last year escalated far beyond the usual complexity of adolescent relationships into intentional, repeated emotional cruelty and injury. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28 percent of students nationwide in grades sixth through 12 experience such torment. Bullying includes unwanted, aggressive behavior that involves a real or perceived power imbalance and repeats the verbal, psychological, or physical intimidation over time. The federal health and human services department outlines many forms: name-calling, threats, social exclusion, rumor-spreading, hitting, spitting, and pushing. Most bullying still takes place on school grounds, but it also happens on the bus, on neighborhood streets, and, increasingly, on the Internet.

Amid front-page headlines that illustrate the fallout, many educators, legislators, and members of the public now regard bullying not as a childhood rite of passage but a serious social problem. From the 2010 first White House Conference on Bullying Prevention to last fall's second annual Iowa Governor's Bullying Prevention Summit, the nation's political leaders have pledged their commitment toward solutions.

Toward this end, the UI has embarked on a multidisciplinary effort to help create a culture shift that no longer perpetuates or tolerates bullying. Whether the behavior has increased markedly over time stirs debate; but, most experts agree that the cyber effect of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other forms of social media have created new and vicious avenues for increased harassment from which there is little escape.

In a centerpiece of UI anti-bullying efforts, Gracie's story informs a new Hancher-commissioned play by Working Group Theatre titled Out of Bounds. Written by associate artistic director Jennifer Fawcett, 08MFA, and produced in cooperation with the John F. Kennedy Center, the community school district, and the UI College of Public Health, the play has been presented at several local junior high schools; a revised version for parents will appear at Iowa City's Riverside Theatre next month. Out of Bounds follows the emotional narrative of three middle school girls, charting the disintegration of their relationship and the development of intense bullying. In an attempt to direct audience members toward empathy and common ground, the play speaks to students in those vulnerable, hormone-fueled junior high years—a time when peers become much more influential and more students begin to access social media.

Says Fawcett: "If more people learn that bullies are really the minority and what they do is uncool—if we can influence the choices kids make in the moment—then I think we'll get somewhere."

The national movement to address the problem of bullying began in earnest after the deadly shooting at Colorado's Columbine High School in 1999. Research by the Secret Service and U.S. Department of Education into 37 school shootings, including Columbine, found that about two-thirds of student shooters felt bullied, harassed, threatened, or injured by others. Although recognizing that such treatment rarely leads to a shooting, schools and policy makers began to approach bullying as a serious and widespread problem that can leave lasting psychological wounds.

PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER O. DRISCOLL/GETTY IMAGES

PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER O. DRISCOLL/GETTY IMAGESStarting with Georgia in 1999, anti-bullying legislation rippled across the country. Today, 49 states (with the exception of Montana) have policies that put a legal responsibility on schools and educators to record incidences and implement preventive measures. One tool already screened nationwide before more than a million kids, teachers, parents, and advocates is the 2011 documentary Bully, which unflinchingly portrays the unbearable school-day circumstances of Alex Libby, a former student in Sioux City, Iowa. Alex used to be friends with his bullies when they were younger, but middle school changed everything. Relationships became about who had the best clothes, hair, and athletic skills. Classmates who once romped with Alex on the jungle gym called him "fishface" and threatened to break his bones and commit sexual assault.

Now living in Oklahoma, the Libby family remains involved in the awareness campaign that the film produced. One effort is The Bully Project website, which invites people to join grassroots chapters against bullying in nearly every state. Another key aspect of the awareness-raising efforts includes properly defining what bullying means. Many people cry "bully" out of context, quick to place any slight, disagreement, rude remark, or difference of opinion under its umbrella. However, the distinction between normal social interaction and true bullying goes beyond kids being kids and accelerates into habitual cruelty.

At its heart, bullying is about power and control. Although some bullies are simply spoiled or mean, many are children who've received harsh treatment in the past from peers or parents, tend to feel powerless, and try to relieve this feeling by terrorizing others. For these children particularly, experts say unchecked bullying can descend further into conduct disorders, substance abuse, truancy, and crime.

For many students, bullying is a daily occurrence. While it can happen to anyone—even a seemingly popular kid like Gracie—children from certain groups carry more risk. Gay, lesbian, and transgendered youth, children with disabilities, and students perceived "strange" for their clothes, interests, quirks, or social awkwardness provide easy targets. Many gifted students exhibit the tender, emotional, against-the-grain characteristics that render them easy prey.

For the victims, bullying makes learning harder, leads to increased anxiety, depression, anger, and low self-esteem, and exacerbates feelings of sadness and loneliness. A study published in the journal Pediatrics recently reported that bullying contributes to poor physical and mental health, especially among children harassed continuously in more than one grade—and the psychological effects can snowball over time. Other studies show the repercussions can also follow victims into adulthood, affecting their ability to hold down jobs, achieve financial stability, or enjoy healthy relationships.

"If more people learn that bullies are really the minority and what they do is uncool—if we can influence the choices kids make in the moment—then I think we'll get somewhere."

- Jennifer Fawcett

In extreme cases, as with Phoebe Prince of Massachusetts in 2010 and Rebecca Sedwick of Florida in 2013, bullying can end in suicide. Both girls experienced online harassment, verbal abuse, and physical threats. Phoebe hanged herself and Rebecca jumped from a silo to her death, prompted by the unthinkable suggestion from their taunters: "Why don't you go kill yourself?"

Massachusetts implemented its anti-bullying policy shortly after Phoebe died, while the aggressors in both cases faced charges of criminal harassment and aggravated stalking—although these charges were later reduced or dropped altogether. Because bullying itself is not considered an actual crime, prosecutors struggle to find grounds on which to convict, especially in Internet cases where the accused often take refuge behind their First Amendment rights. In addition, some experts argue that society doesn't need more criminal laws, but an honest conversation about civility, compassion, resiliency, and respect.

A sweet-faced seventh-grader with braces, James Zierke is the quintessential smart, sensitive kid who dances to his own inner music. His emotional vulnerability makes him a natural target for bullying, which he's endured in cycles since the second grade. Kids tease him for liking to talk to girls more than boys or choosing to play the flute in band. In their opinion, the fact that he likes to draw knives and weapons in the margins of his spiral notebooks means he must be a violent weirdo (not a young man who aspires to be an engineer for the U.S. military). Bullies have thrown him off the playground swings and kicked him in the back of the head. They've yanked branches from weeping willows and turned them into whips to slap his arms and legs. They've called him a wimp.

Pushed to his limits, James increasingly responded in emotional, angry ways that violated other school behavior rules. In turn, teachers often considered him the problem student—and he ended up feeling punished for being bullied.

At the beginning of his sixth-grade year in a North Liberty, Iowa, area school, sensing her son's anxiety and depression, Shawn Zierke asked James a question: If you could change three things about your life, what would they be? "His first wish was for someone to install cameras and microphones in the schools so teachers could see what's really happening, believe him, and fix things," says Shawn, 12BA, a UI graduate student in public health. "He felt like no one had his back."

James isn't alone in feeling unsupported in his battle: on a national scale, two-thirds of students believe schools respond poorly to incidences of bullying. At the UI, a professor from the College of Public Health aims to improve that situation. Marizen Ramirez, associate professor with the Department of Occupational and Environmental Health and associate director of the UI Injury Prevention Research Center, explains that bullying is more than an education issue. "It's associated with a number of adverse health outcomes, such as depression, which makes it a public health priority," she says. "Schools cannot do this alone."

PHOTO: THINKSTOCK.COM

PHOTO: THINKSTOCK.COMRamirez is working on several ongoing studies about bullying victimization, including one Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-supported project that investigates the implementation and effectiveness of Iowa's 2007 anti-bullying law. Partnering with several middle schools across the state, she's charting how they comply with the legislation—and, more importantly, whether their programs appear to reduce bullying and improve teacher intervention.

Every state approaches its anti-bullying laws differently, but Iowa requires that schools define harassment and bullying, apply a procedure for reporting/investigating complaints, include consequences for those who violate policy, and submit incident statistics to the state. Early data from Ramirez's study show an initial post-legislation increase in incidences, which she attributes to better reporting, followed by a decrease that seems to offer evidence of the law's potential effectiveness. Eventually, Ramirez hopes to identify best practices that schools can adopt to make a difference in the lives of vulnerable children.

In two other studies, Ramirez is assessing the effectiveness of novel approaches to changing bully culture. The first analyzes the power of the arts—in this case, Fawcett's Out of Bounds play—to see whether such efforts increase students' awareness, empathy, and willingness to stand up for victims. The second project harnesses the power of the same technology that makes cyberbullying so prevalent and potent. Using a National Institute of Justice grant, Ramirez and colleagues from the UI's sociology, community behavioral health, and computer science departments are developing an application that volunteer junior high students can download on their phones. Researchers will then review the content and context of the electronic activity to better understand what type of language constitutes cyberbullying and on what social networks it occurs.

Meanwhile, the UI College of Education's Teacher Leader Center is pouring resources into the frontlines—helping future educators cultivate positive, respectful classroom environments. Opened in 2011, the Teacher Leader Center provides education students professional development and leadership skills, as well as academic advising. Working in a K-12 environment requires far more than a command of curriculum fundamentals, points out William Coghill-Behrends, 03MA, 05IED, the center's educational support services coordinator. Teachers also have to navigate the complex landscape of childhood's social and emotional dynamics.

When the center first opened, Coghill-Behrends immediately thought about presenting a series on bullying. Then, in 2012, he read about the suicide of 14-year-old Kenneth Weishuhn of Primghar, Iowa, who suffered repeated, vicious bullying in the weeks after coming out as gay. Unable to see any promise of a bright future, Kenneth hanged himself in the family garage.

"That was the last straw for us," says Coghill-Behrends, who helped develop the Teacher Leader Center's 2012 yearlong program "Stop the Bully, Find a Solution." In solidarity with the state's heightened focus on bullying awareness, the program featured more than 36 community workshops led by UI faculty and national leaders to give future teachers research-based resources and strategies to fight the problem. (The effort continues this year with monthly workshops.) Beginning with the first event, "Bully Prevention 101," the series addressed topics such as LGBT issues, race, disability, suicide prevention, and the long-term medical consequences of bullying.

"All of us can think of a time when we felt victimized, or were the bullies, or didn't intervene."

- William Coghill-Behrends

The workshops opened not only to the UI students, but also to local teachers, school administrators, and the public. "People thanked us for doing what we could to develop teachers who will be important 'up-standers' for students," says Coghill-Behrends. "We often hear from the administrators who hire our teachers about how they come to school able to hit the ground running."

By the last workshop, Coghill-Behrends was overwhelmed by the attendance and response. He was especially touched by the personal, emotional letters from adult participants who revealed the ways they still felt the impact from bullying suffered in their childhoods.

"I think all of us can reach back and not only think of a time when perhaps we felt victimized, but also a time when maybe we were the bullies," he says. "Maybe we picked on someone we thought was a little odd. Maybe we observed a situation or a conversation that made us uncomfortable but we didn't intervene."

Gracie Schulte was alone when she saw the fake Instagram page. Sobbing, she called her parents, who had left for an evening out. Mary Pat and Mike rushed home and called the school principal the next day.

Although Gracie suspected some of her fellow singers were behind the Instagram assault, she still held out hope that people who were once such an important part of her life wouldn't stoop so low. But when the principal's door opened, the truth came out. Two former friends had done it—with help from an older sibling. The next day was the last day of school, and the girls involved received a suspension.

"I was so hurt for her," says Mary Pat, recalling the look on her daughter's face that day. "Grace had a long, lonely summer."

Before the start of the new school year, Gracie met face-to-face with her bullies to clear the air. While tense, the conversation bolstered her courage to move forward. So far, eighth grade seems brighter. She's investing in truer friends, the sparkle has started to return to her eyes, and she speaks with the newfound confidence and wisdom that comes from weathering a dark storm.

"I'm much more careful about who I place my trust in," she says. "I learned to be true to myself. I don't need to be anyone else."

James has also taken proactive measures to better cope with his school days. He works harder to see his role in difficult situations and has learned to better control his responses. As a result, he's receiving more support from teachers and his principal. "I just want people to realize what they're doing," James says. "I want to make them not so mean."

Already, some evidence suggests his wish may one day come true. Jennifer Fawcett sees it in the emotional reactions of students who attend her play—in the moments when they register the painful consequences of bullying. Iowa City's West High Bros., a group of students who garnered national attention for their positive Twitter campaign, keep working to "make someone's day a little brighter" through congratulatory tweets, while Tipton High's first male cheerleader recently launched a kindness project. In addition, all Iowa City elementary schools promote the Steps to Respect program that teaches students to recognize, refuse, and report bullying.

"Kids are mean and going to be stupid or disrespectful," says Shawn Zierke. "But there's a difference between that and persistent abuse that changes how a person feels inside. If the culture doesn't allow it, perhaps we can make bullying go away."

Ironically, the theme of Gracie's show choir this year is bullying—selected before the unfortunate events of last spring unfolded. Gracie sings the solo ballad, which Mary Pat considers an interesting cosmic twist, and she does so with the heart, emotion, and voice of experience.

Earlier this year, the choir participated in its first competition, and, as Gracie struck her last note, the tears cascaded down her face. Afterward, the friend she'd valued most—the one who had told her to rot in hell—offered a sincere apology. He saw her pain, he was sorry for betraying her, and he asked for her forgiveness.

In that theater, two people on opposite ends of a difficult journey learned a lesson about hope, healing, and reconciliation. They learned about the profound promise of change.

Prevention 101

Many bullied children don't ask for help because they are embarrassed, feel helpless, fear retaliation, or simply don't know what to do. Some warning signs to look for include unexplainable injuries, lost or destroyed possessions, frequent complaints of illness, a change in eating or sleeping habits, declining grades, sudden loss of friendships, avoidance of social situations, and self-destructive behaviors.

Adults who see bullying happen should be prepared to intervene immediately, separate the kids involved, make sure everyone is safe, meet any medical/mental health needs, stay calm and reassure, model respectful behavior, and teach children to respect authority. Kids help when they treat all peers with kindness, don't give bullying an audience, talk to trusted adults, set good examples, and reach out in friendship to bullied children.

Source: www.stopbullying.gov

OTHER WEBSITES:

IT HAPPENS EVERYWHERE

Bullying is not an issue contained to the classroom. The behavior occurs everywhere power dynamics exist, from the workplace to the NFL locker room.According to a recent Career Builder Survey, as many as 35 percent of American workers report they've felt bullied at work. The Workplace Bullying Institute defines the phenomenon as repeated, harmful harassment that can include verbal abuse; threatening, humiliating, or offensive behaviors; and work sabotage. While employment protections exist for workers who belong to a certain race, sex, disability, or whistle-blowing class, most employees have few options for recourse. Many simply quit their jobs and look for employment elsewhere.

Although the National Football League is not a typical office environment, one high-profile case last year dramatically highlighted the issue of workplace bullying. Miami Dolphins starting offensive lineman Jonathan Martin (pictured) claimed he'd suffered persistent harassment that led to his abrupt departure midway through the season. An official NFL investigation concluded that three starters on the Dolphins offensive line engaged in a pattern of harassment—including racial and homophobic slurs, sexual taunts, and improper physical touching—aimed at Martin, another young offensive lineman, and an assistant trainer. The report resulted in the firing of the Dolphins offensive line coach Jim Turner and head trainer Kevin O'Neill for going against the "core values" of the organization.

Since then, the NFL has taken steps to create an atmosphere of respect and tolerance. In an editorial just last month, the New York Times suggests this will require a shift in society's expectations for athletes: "It was not so long ago that accounting firms and law offices excused sexual harassment as boys-will-be-boys high jinks. But in recent years, most workplaces have tried hard to move beyond the vulgarity and aggressiveness of the Mad Men days, and certainly beyond racial animosities. Locker rooms should do the same."

For more information, visit www.workplacebullying.org.