The most certain thing about life is death. It eventually comes to every human being, and, like birth, it is a phenomenon we all share.

Also like birth, the death of a person is a huge transition. A piece of the world, the community, the human experience is no longer there, and both family and community must respond and adapt to the change. All over the globe, funeral customs mark such losses, with rituals as varied as the cultures that make up our world.

In her class "The Anthropology of Death," UI anthropology professor Katina Lillios examines the historical and modern-day customs of many regions—not only how they honor the dead, but also how they reflect a society's ideologies about life. Social inequalities, gender roles, religious beliefs, and even values regarding time and money all become transparent against the stark backdrop of death.

Whether a group buries its dead in a flower-draped coffin, in the empty branches of a tree, or in the "sky" atop a mountain, whether it entombs, embalms, burns, or eats the flesh of its corpses, a common theme motivates all actions: to transport the departed to their rightful place in the "land of the dead." With a mix of celebration and fear, rituals make death official; they fulfill certain cultural requirements that ensure the dead have been delivered to the Other Side, wherever that may be, so that the living can move forward in peace.

Here are six approaches to death that are examined in "The Anthropology of Death."

At the UI, Professor Lillios finds that her students appreciate the opportunity to talk about death in a thoughtful, critical way. Through the universality of death, they learn to appreciate cultural differences; even the strangest ritual becomes understandable when considering the compelling logic behind a practice. Through death, they discover ways of grieving, coping, and comforting that illuminate our shared humanity.

"Thinking about death creates opportunities for pondering a meaningful life," says Lillios. "It forces us to think carefully and clearly about what's important."

United States

Death is not a topic openly discussed in U.S. culture—which only elevates a sense of mystery and the macabre surrounding the subject. Not that long ago, Americans had more personal contact with the dead; death often occurred at home, and family members prepared the body for burial. Now, funeral home directors typically manage those time-consuming preparations, which is necessary in a society reluctant to give citizens ample leave from work for either birth or death.

In the U.S. today, a diverse set of cultural and religious values find expression at death. Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus—all have different views and practices to carry out. Generally speaking, however, individualism emerges as a value most clearly emphasized during death rituals in the U.S. Loved ones bury their dead in separate graves, sometimes spending thousands on preserving the body and purchasing expensive caskets for interment. If a dead person is cremated, the ashes are brought carefully together in the urn. In addition, a dead person's achievements, personality, and relationships are celebrated in obituaries and memorialized on individual tombstones.

While there's an undeniable disconnect between the dead and the living in the United States, many people still maintain relationships with their dead through gravesite visits, a beloved picture of Mom in a heart-shaped locket, or Grandpa's guitar in the back of a closet.

Neolithic Europe

PHOTO: HEIREANN/WIKIPEDIA

PHOTO: HEIREANN/WIKIPEDIAIn contrast to the highly individualized final resting places in modern America, Neolithic Europeans between 6000 and 2000 B.C. buried their dead in collective tombs. The remains of anywhere from a few to hundreds of adults and children occupy large stone tombs—known as megaliths—or caves dated to this time. To Neolithic people, the dark recesses of a cave or stone tomb were the proper places from which to journey to the next world.

It's difficult to pinpoint exactly what values or belief systems these agricultural people intended to express in their ancient practices, but it's reasonable to suggest that group identity (as represented by the collective tomb) was more important than individual identity. The organization and effort required to erect the megalith's large stone slabs show that these people were willing to work in groups to ensure the appropriate treatment of their dead.

Tibet

As Buddhists, Tibetans believe in reincarnation, and the process of rebirth is said to take 49 days. During this time, certain rituals specific to Tibetan Buddhism occur—including, ideally, reading the Tibetan Book of the Dead to the shroud-wrapped body, where the spirit is thought to still reside. This recitation guides the spirit through the period between death and rebirth. (In Tibetan Buddhism, this critical time is called "Bardo" and has profound influence on helping the departed get to their proper destination.)

Tibetans practice cremation, water burial, and, occasionally, tree burial for children (where a corpse is placed in a wooden basket and hung in a tree). But, by far the most widespread practice among Tibetan commoners is "sky burial." Instead of attempting to bury bodies in the region's hard, rocky ground, they place their loved ones on mountaintops to be chopped up by a corpse disposal specialist and to be consumed by vultures (considered a sacred bird). The body and flesh are impermanent carriers and have no significant meaning. Offering the body to other creatures is a meritorious act that reflects Buddhist beliefs about the interconnectedness and interdependence of all living beings.

China

PHOTO: SAMPUNA/WIKIPEDIA

PHOTO: SAMPUNA/WIKIPEDIAAge, social and marital status, and cause of death all determine the type of ceremony a person receives, but it's generally believed that improper funeral arrangements can wreak disaster on a family. Traditionally, Chinese funeral rituals and sacrifices are intended to transform a potentially dangerous spirit of a dead person into a benevolent ancestor. As Chinese believe their dead ancestors continue to influence their lives and good fortune, it's important to include and honor them at transformative family events like weddings and funerals. Often mourners create home altars from which to make offerings and worship their departed loved ones.

Without proper rituals or sacrifices, a person can become a ghost—souls that remain on Earth to cause trouble for the living. Some ceremonies are similar to those found in Tibet, as Chinese offer prayers and penance and burn incense to purify a soul and guide it from death into the afterlife. A soul can also become a ghost if tragedy surrounded that person's life and death. Taken very seriously, Chinese death ritual involves the participation of multiple relatives and reflects the importance of the extended family, both dead and alive.

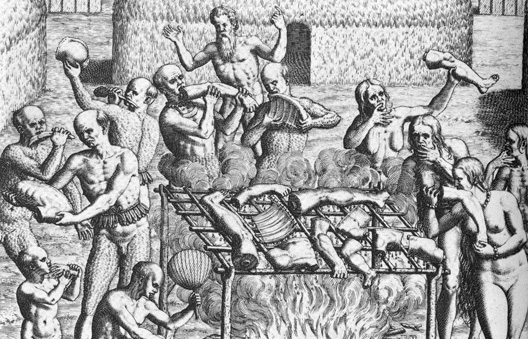

art: hans staden (b. around 1525, Wolfhagen, 1579)/wikipedia

art: hans staden (b. around 1525, Wolfhagen, 1579)/wikipedia WESTERN BRAZIL (WARI): For Wari' of Western Brazil, funerary rituals help loved ones forget their dead and heal from grief. To erase all trace of a dead person, Wari' destroy the deceased's possessions and do not speak the name of the dead. Up until the 1960s, they ate the roasted flesh of the corpse as an expression of respect and compassion for the dead, as well as the family, and to eliminate what they perceived as the strongest symbol of loss.

According to anthropologist Beth Conklin, 80MA—who completed extensive fieldwork among Wari' in the 1980s and 1990s—placing a loved one in the cold, wet ground is as horrifying to Wari' as cannibalism is to Western society. Although the government and missionaries forced Wari' to abandon the practice (they now reluctantly bury their dead), Conklin maintains the tradition was performed with the same elements of emotion and empathy that people around the world share.

PHOTO: TOM OATES

PHOTO: TOM OATES GREECE: Secondary burials traditionally were a key part of funeral rites in rural Greece. In this ritual, a body is buried for some years, exhumed, and the bones reburied in a grave or placed in an ossuary. The two-part mourning process subscribes to certain beliefs about the afterlife—that the state of a body informs the living about the fate of the deceased's soul. Secondary burials reflect the view of death as a prolonged process, in which the living and dead need time to adapt to their new social statuses.

Exhumation after anywhere from three to seven years allows loved ones to reunite with the dead one last time before final burial and marks the end of the mourning period. Plus, it allows the living to assess the moral state of the dead. If the bones are clean (without flesh), then it is thought that the deceased's soul has separated from the body, that sins have been forgiven, and the soul has entered paradise. At that point, the mortal remains are now ready to join the ancestors. If flesh remains, the soul has not separated; as it is subject to reanimation by evil spirits, possibly becoming a revenant (or vampire), the body is reburied.