With help from the University of Iowa, a determined alumnus transforms a senseless crime into an unexpected blessing.

With help from the University of Iowa, a determined alumnus transforms a senseless crime into an unexpected blessing.

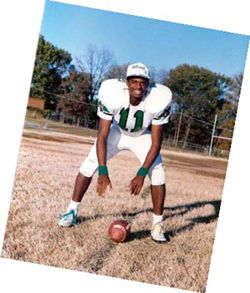

That steamy June evening in Memphis, Phillip Lewis sat in his car and thought about his bright future that stretched ahead. He'd worked hard at community college to improve his grades, and the University of Memphis had recruited him as a linebacker. With summer camp only two weeks away, his cherished dream of playing football was about to come true. Perhaps one day, he'd even make it to the pros.

The bullet shattered that dream in a split second. The bullet changed everything Lewis, 04PhD, thought he knew about himself and life.

As he waited outside a friend's house, Lewis didn't take much notice of the group of teenagers loitering nearby. Even though the Memphis native wasn't in his usual neighborhood, he didn't worry—until one of those kids stuck a gun through the window of his car and shouted an obscenity.

Lewis didn't wait to find out whether the kid wanted his jewelry, his vehicle, or his money; he shoved the car in gear and drove away. The gun exploded, sending a bullet through Lewis's right arm, across his chest, and out his left arm. Somehow, he found the strength to drive, steering the car several blocks in second gear until he found a safe place to stop for help.

A few days later, an orthopedic surgeon came into his hospital room with grim news that he didn't attempt to break gently. "You're never going to play football again," he said. "You'd better apply for disability."

Even now, 20 years later, Lewis clearly remembers the words that swept him into a downward spiral of despair. The bullet caused permanent nerve damage in his hands, leading to two surgeries and an enduring legacy of weakness, pain, and discomfort. The toll on his mental and emotional health proved far greater. Reeling from post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, he even contemplated suicide.

Instead, the fateful bullet that sent his life ricocheting in a new direction made him determined to forge a different path. At such pivotal moments, he explains, "You really connect with the reality of life."

Lewis never again met the youth he believes shot him (the 14-year-old was acquitted of that charge, but eventually ended up in jail for another, unrelated crime). He knows his kind all too well, though. Growing up, he'd seen plenty of people he disparagingly refers to as "hustlers." Even a player on his high school football team used to boast that he made $10,000 a week selling drugs.

"Where I come from," says Lewis, "education isn't seen as a way to a better life."

Football saved Lewis from drugs and crime. So did the rock-solid support of his mother, Claudia Peterson. Ironically, Lewis was shot on her birthday. "She reassured me it would be alright through prayers and God," he recalls.

"My mother helped me believe it would be okay, even though I didn't know how I would recover." Two years after the attack, Lewis remained crippled psychologically; scraping by on disability benefits, he rarely ventured outside his home. Then, a member of his high school football team suggested he return to college. With the support of that friend and the faculty at Rust College, a traditionally black institution in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Lewis discovered a new passion: education.

Although he became an excellent student, his transition from athlete to academic was far from easy. With his handwriting ability affected by the nerve damage, he needed extra time on tests. Professors allowed him to record lectures instead of struggling to take notes. After four years, Lewis became the first man in his immediate family to graduate from college, earning a bachelor's degree in social work from Rust. Deciding to specialize in rehabilitation counseling, he went on to earn a master's degree from Southern Illinois University and then a Ph.D. in rehabilitation counseling education and law, health policy, and disability at the University of Iowa.

His experiences made him a perfect fit for a career helping people with disabilities achieve their personal, social, psychological, and vocational goals through counseling, advocacy, and case management. "I don't want anyone to feel like I did. When you're young, you shouldn't have to think about suicide," he explains. "I want people with disabilities to feel they can do what they want to do."

Lewis still remembers the culture shock he experienced moving to Iowa, a place far removed geographically and culturally from his Southern home. When he interviewed for graduate college in winter, he shuddered at Iowa's freezing temperatures, remarking to a College of Education faculty member that the cold made his damaged hands ache.

"That's alright," responded Dennis Maki, professor of graduate programs in rehabilitation, who went on to become an important mentor and friend. "It's warm in the library."

While Lewis braced to encounter racism, he was pleasantly surprised by the supportive atmosphere— demonstrated through friendly people, as well as grants and scholarships from the UI Graduate College. "Iowa City is a unique environment, especially for someone from inner-city Memphis," he says. "I interacted with people from all over the world, and I became much more cross-culturally competent."

Now an associate professor and graduate coordinator of the rehabilitation counseling program at Langston University in Oklahoma, Lewis is helping train the next generation of counselors, particularly much-needed minorities. "There shouldn't be disparity between the races of people who give and receive services," he says. "It takes time to develop rapport [between counselor and client]. Race shouldn't be a barrier, but until we grow as a society, issues of trust will exist."

The counselor's efforts to pass on lessons learned from his shooting don't stop with his career. He's determined to help prevent minority and at-risk youths from ending up on either end of a gun.

Since his days at Rust, Lewis has volunteered his time to work with such kids. He wants to give them something he'd never had growing up: a positive role model. In addition to offering himself as an example of a successful African-American, Lewis brings different professionals to his group sessions to highlight the better opportunities available through education and hard work. "Kids follow what they've been exposed to. They need alternative direction to make better choices," he says. "It's not hip to be smart these days, especially in the black community."

Indeed, Lewis despairs at the lack of respect for education that seems rampant among many youngsters, whose idols are more often pro athletes, misogynist rap stars, and criminals than doctors, teachers, or engineers. Many of the kids he works with ask why they should bother earning $400 a month at a minimum-wage job, when they could make that much in a day by breaking into houses and stealing.

While he's supportive and encouraging, the former linebacker is no soft touch. "Success without merit is obsolete," he shoots back. "You need to take responsibility for your lives."

That's a lesson he learned the hard way, but his efforts paid off. Years after the shooting, Lewis sought out that orthopedic surgeon who'd shattered his dream of a football career. Not only was his life far from over, he proudly pointed out, but he was earning a Ph.D. and working to ensure that other youngsters wouldn't be cast adrift in the same way.

Nothing would stop him in his drive to help others overcome adversity. Not even a bullet.

UI Rehab History

The field of rehabilitation counseling began after World War I to serve the needs of veterans and workers injured in industry.

The profession experienced major growth in the 1950s, with federal recognition and training funds. Established in 1956, and recently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News and World Report, the UI College of Education's program offers both an M.A. degree in rehabilitation counseling and a Ph.D. in rehabilitation counselor education.

Historically, the program has produced many leaders in the field, including:

Beatrice Wright*, 40MA, 42PhD, whose groundbreaking research planted the seed for the rehabilitation tradition at Iowa, and who went on to develop the theory of somatopsychology (the influence of bodily characteristics on personality traits);

Marceline M. Jaques, 46MA, 59PhD, the first woman in the nation to receive a doctoral degree in rehabilitation counselor education and then to direct a program in this field;

C. Esco Obermann, 27BA, 31MA, 38PhD, [deceased] who wrote the definitive text on the history of vocational rehabilitation and chaired the National Rehabilitation Counseling Association ethics committee that drafted the profession's first code of ethics in 1968.

About 120,000 rehabilitation counselors currently practice in the United States, addressing the vocational, psychosocial, and independent living needs of the estimated 49 million people with physical, cognitive, emotional, social, and developmental disabilities.

With America's increasing incidence of disability, aging population, growing state and federal emphasis on extending opportunities to people with disabilities, and evolving legal, policy, and technological developments, the need for qualified rehabilitation counseling professionals is expected to grow.

For further information about the UI program, visit www.education.uiowa.edu/rehab/program.