Mother's Memoir Inspires New Book From Iowa Alumnus Abraham Verghese

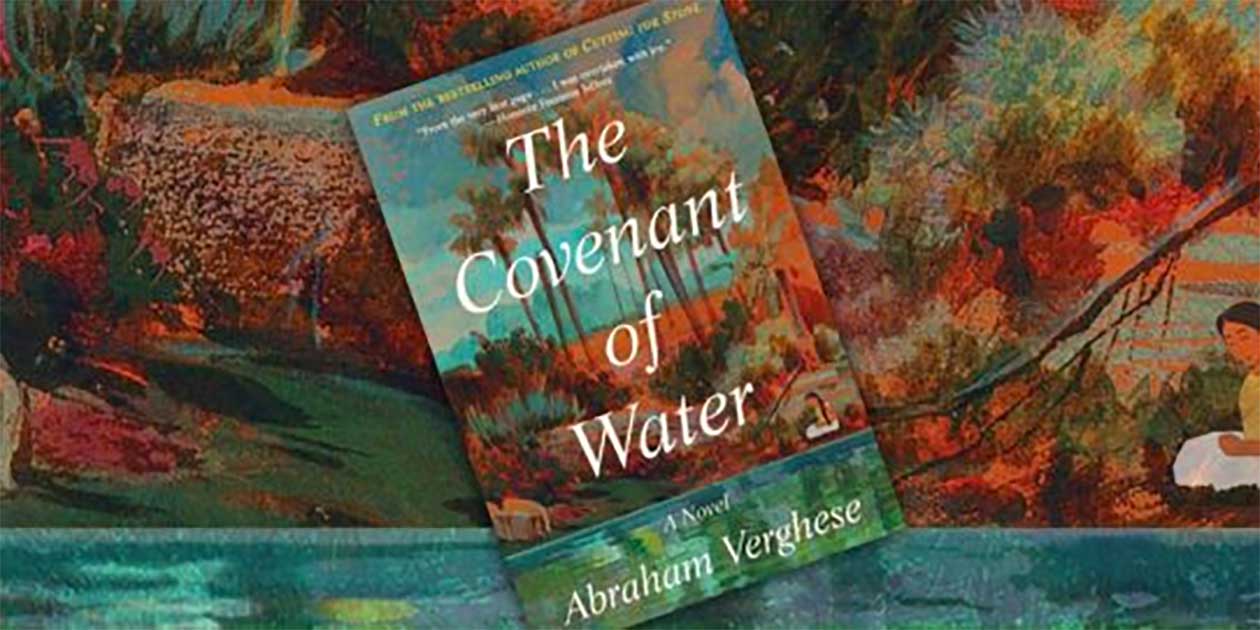

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (91MFA), Grove Atlantic, 736 pp.

An Oprah Book's Club selection, The Covenant of Water is about an Indian family who gradually discovers the truth behind a generational curse that leads to drowning.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (91MFA), Grove Atlantic, 736 pp.

An Oprah Book's Club selection, The Covenant of Water is about an Indian family who gradually discovers the truth behind a generational curse that leads to drowning.

Abraham Verghese’s newest book, The Covenant of Water, is an epic novel spanning three generations of a family in Kerala, India, that opens with the arranged marriage of a 12-year-old girl to a much older widower. It’s an inauspicious start, says Verghese, but turns into a love story and the little girl becoming a wise matriarch.

It was his own mother’s artistic prowess, in fact, that inspired the author. Some 20 years ago, his niece asked Verghese’s mother what it was like growing up in Kerala, which prompted her to write a 100-page manuscript by hand, complete with illustrations, detailing family stories and everyday life. Though Verghese’s family is from Kerala, he grew up in Ethiopia, where his parents were schoolteachers. Every summer, they traveled back to Kerala to visit his grandparents.

PHOTO: JASON HENRY

Abraham Verghese

PHOTO: JASON HENRY

Abraham Verghese

“I had the unique experience of being an outsider looking at these rituals of a life that felt as if it had been cast back in time,” said Verghese, who is also a professor of medicine at Stanford University.

Verghese’s first novel, Cutting for Stone, was a bestseller in 2009. He’s written two memoirs and received, among many other awards, the National Humanities Medal from President Obama in 2015.

How has your life as a medical professional influenced your writing, and vice versa?

This might sound disingenuous, but I actually resist this attempt to chop me up into labels: writer, physician. I feel like my writing emanates from that worldview as a practicing physician. It doesn’t feel like something entirely separate; I worry that if I stopped practicing medicine, I would lose that lens through which I look and write. I’m sure that’s not true, but physicianhood feels very much a part of me.

Iowa City is obviously a city of both medicine and literature. How did your time at the workshop lead to your first memoir, My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story?

The reason I was there was because I had a story to tell. I had just lived through an extraordinary experience of being an infectious disease expert in a small town in Tennessee, where the predictions in 1985 were that I might see one or two patients a year because AIDS was believed to be an urban disease. Instead, in a short time, I was following about 100 people with HIV. I realized that I had stumbled upon an American paradigm of migration.

The paradigm is this: A young man grows up in a small town and leaves because he is gay and doesn’t want to live that lifestyle under the scrutiny of friends and relatives. And so, he went to the big city and found himself; decades later after his partner died from HIV, he was coming home to be cared for. I wrote a scientific paper describing this migration, but I felt at the time that that paper didn’t do justice to the tragic nature of this voyage, or the grief of the families, or my own heartache at seeing men my age succumb to a fatal infection. I came to Iowa at a very strange time in my life, in my mid-thirties, with a wife and young children, slightly burnt out from the intensity of caring for so many with HIV, but determined to keep doing it forever, albeit with breaks to regroup. I came to Iowa with a mission, a story to tell.

As you talk, I’m thinking about the way in which medicine, the body, literature, and the spirit are connected. It seems these two things—medicine and literature—are much closer than we ever want to place them.

I have this great privilege—and sometimes misfortune—of being a witness to people at their most intense and dangerous and, sometimes, tragic moments in their life. There is a sensibility that comes out of that experience that informs the writing. Whether one’s a physician or not, we are all still engaged in that same uncertainty, the fear and denial of our mortality, the struggle to find meaning, the redemption that comes through love and family. We’re all juggling the same things.