The Night Bruce Springsteen Unleashed a Rock Tsunami at Hancher

PHOTO COURTESY DAVID SITZ

The author, pictured here in the early '70s, holds the UI School of Journalism and Mass Communication's first portable video camera.

PHOTO COURTESY DAVID SITZ

The author, pictured here in the early '70s, holds the UI School of Journalism and Mass Communication's first portable video camera.

On a Friday night in late September 1975, Bruce Springsteen and his E Street Band brought the Born to Run tour to Hancher Auditorium. The album had been released a month earlier and was quickly garnering critical acclaim. Springsteen and the band were more than two months into a tour that had already covered the East Coast before making a swing through the Midwest, including a stop at Grinnell College a week before the Hancher show. One month after the Hancher appearance, Springsteen would grace the covers of both Newsweek and Time. As he took the stage that September evening, a rock tsunami was already building.

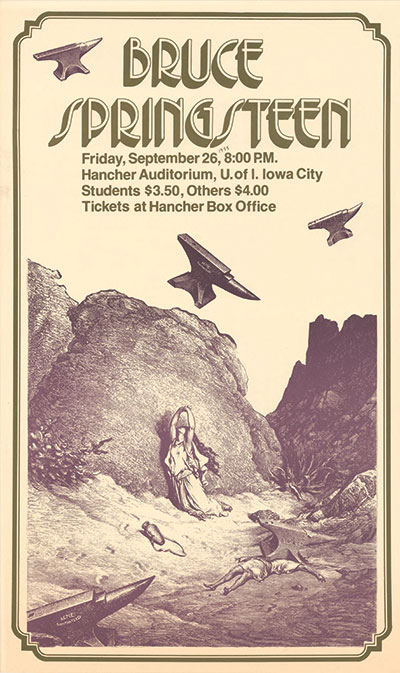

POSTER: IOWA DIGITAL LIBRARY, UI LIBRARIES

POSTER: IOWA DIGITAL LIBRARY, UI LIBRARIES

The Hancher Entertainment Commission, a University of Iowa student group, promoted the show. It was the first led by John Gallo (78BGS), my longtime friend and HEC’s new student director. Since the Springsteen juggernaut was still in its early stages, HEC had booked the show for only $2,500.

One of the first productions of the fall semester, the show was just short of a sellout of 2,600 seats. Student tickets were $3.50. But Gallo remembers some tense moments between Springsteen’s road crew and Hancher technicians over sound quality that could’ve ended the memorable night. “At one point right before the sound check we even threatened to cancel the show,” Gallo explained recently. “Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed.”

I had arrived on campus five years earlier as a journalism student. The atmosphere had changed after campus riots in spring 1970 disrupted the university, sending thousands of students home early. That fall, university administrators invited greater student involvement—including with organizing concerts—as a way of ameliorating their discontent.

I began writing music and movie reviews for The Daily Iowan in ’71. That spring, Don Pugsley (77BGS), a Vietnam veteran and student from Des Moines, ran a successful campaign to get the Grateful Dead to play the Field House. Campus security nervously looked on in fear of chaos as concertgoers who wanted to stand or move around during the performance ceremoniously passed the wooden folding seats set up for them to the rear of the floor. It was one of the first concerts I attended, and the band’s improvisational jams hooked me on the communal energy of live music.

In fall ’72, I joined the newly formed Commission on University Entertainment, with Pugsley and Bev Horton (73BGS) as co-chairs. CUE had replaced its predecessor, Central Party Committee, which had disbanded after budget shortfalls on several concerts.

At the same time, Hancher opened with its first concert by the Preservation Hall Jazz Band. The new auditorium had been designed and built as a theatrical showcase, one of the finest in the Midwest. “Hancher was conceived as an artistic laboratory,” Jim Wockenfuss, the university’s director of cultural programs at the time, told me. “Student involvement was at the core of its existence.”

Students served as ushers, technicians, maintenance workers, and administrators at Hancher. They also helped coordinate concerts through HEC.

We were all new to the concert business, learning as we went. I personally learned more from my time at Iowa as part of CUE and from the laboratory curriculum in the School of Journalism than I did in any classroom. Through CUE and HEC, students gained invaluable experience in everything from the performing arts to entertainment promotion.

After I graduated in ’74, I stayed in Iowa City taking various jobs before accepting a position in the ad department at the Press-Citizen. My relationship with CUE and HEC continued in an advisory capacity, including helping backstage, watching shows from the wings, and consuming free beverages—all of which led to that fateful show in September ’75.

I had loved Springsteen ever since wearing out his second album, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, in late ’73. That led me to his first album with Columbia, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. At a time when singer-songwriters like James Taylor were popular, Springsteen’s gritty stories appealed to me. And they rocked. He was shaking off the whispers of “the new Dylan” and creating something different. As someone from a quiet corner of Iowa, I related to his message of escaping from the confines of a small town looking to discover a bigger world.

In late ’73, I produced and narrated a radio tribute for Springsteen that was broadcast on KSUI as part of a journalism project. But I had never seen him or the band in concert before the Grinnell show in 1975. That concert was held in Darby Gymnasium in front of about 300 people. Darby was smaller than some high school gyms, which was quite a contrast from playing to recently sold-out clubs in the Northeast in front of a skeptical but later adoring press. I had been reading the reviews of Born to Run and knew what was beginning to happen on a national scale. The small Grinnell show only primed us for what we would witness the following week.

For musical context, 1975 was the year of A Night at the Opera (Queen), Blood on the Tracks (Bob Dylan), Tonight’s the Night (Neil Young), and Fleetwood Mac. It was also the year of Physical Graffiti by Led Zeppelin, which famously played the main ballroom of the Iowa Memorial Union on its first U.S. tour in 1969.

At the Hancher concert, I found a place near the soundboard where I could take in the performance and tap into the crowd’s energy. Springsteen opened with the haunting “Meeting Across the River.” It marked the first time he performed the song live from the still new Born to Run. What little uneasiness I sensed in the crowd was quickly remedied by a scorching “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out.” From that moment, the crowd remained on its feet the entire show.

Springsteen and the band—including Roy Bittan on piano, Clarence Clemons on saxophone and vocals, Danny Federici on organ and accordion, Garry Tallent on bass, Steve Van Zandt on guitars and vocals, and Max Weinberg on drums—had become adept at working the audience into a frenzy. Springsteen used Clemons as a perfect foil on stage. Their back-and-forth banter let the audience and band catch their collective breath before unleashing a furious finale.

Springsteen played most of Born to Run including “Thunder Road,” a rousing “Jungleland,” and one of my favorites, “She’s the One.” The concert closed with “Detroit Medley” (including “Devil With a Blue Dress On,” “Good Golly, Miss Molly,” and “C.C. Rider”) and Gary U.S. Bonds’ “Quarter to Three,” sandwiched between “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy).” The show has been played several times on SiriusXM E Street Radio. It’s considered among the best of the band’s concerts from that tour.

Springsteen and the band were hitting their stride. The energy they brought that night was contagious. It was an amalgam of rock, soul, rhythm and blues, gospel, and sheer joy. You left feeling exhausted and exuberant at the same time. Or at least I did.

That night we were witnessing an artist on the cusp of stardom. Before Born to Run, Springsteen was shy onstage—caught trying to be the confessional singer-songwriter of his first two albums, yet yearning to unleash the creative flood of Darkness on the Edge of Town, The River, and Born in the USA. Indeed, before Born to Run was released and hailed, Columbia was on the verge of releasing him from his contract in favor of other artists like Billy Joel.

That all changed in the late summer and early fall of 1975 as Hancher Auditorium and 2,600 participants caught a wave that was about to carry the music world away.