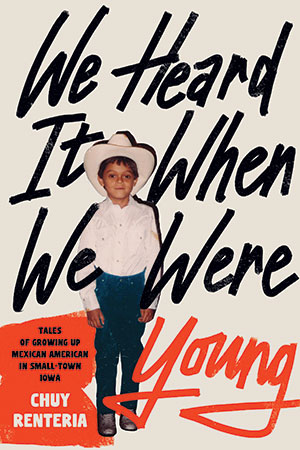

Lessons in B-Boying

PHOTO COURTESY CHUY RENTERIA

Author Chuy Renteria's childhood friend, Jerry Sayabath, break dances in 2000 in West Liberty, Iowa.

PHOTO COURTESY CHUY RENTERIA

Author Chuy Renteria's childhood friend, Jerry Sayabath, break dances in 2000 in West Liberty, Iowa.

I knew what I had to do before she even hung up the phone. My first real girlfriend was breaking up with me. She wasn't even breaking up with me. She had gotten a friend to call me and break up with me for her.

How pathetic was that? When I clicked off my house's cordless phone, I clicked it right back on and called Jerry Sayabath. It was time. I was ready.

"Jerry? It's me. Yo, you still got that Battle of the Year '97 tape you guys were watching? Could I borrow it? Like come over right now and grab it from you? Yeah, like right now right now. Okay, I'll be over."

That was it. That's when I started breaking. That's when I flipped the switch and began a 20-year career in dance. That's when I made the first step of the journey away from the wall where I would watch the Laotians dancing at the mobile court toward that self-guided path to identifying as a b-boy.

It was 1999 and a lonely summer was ending. I had turned 14 years old at the end of July. Going to Jerry's that day was a last-ditch desperate attempt to figure out what the heck I was doing with my young life. Things had been getting worse and worse since my good friend Ruben and I had a fight to end all fights at the beginning of summer. Since I had started running with a new group of friends, friends who were causing more destruction than the gang at the Shack—the name we'd given to our hangout spot in Ruben's garage—ever did. Since I started shunning them and got a girlfriend. I tried to pour everything into her until she had her friend call me on the phone to say, "She just thinks it would be better if you guys were friends." I later learned that my now-ex was listening on the other line for my reaction.

My world was crumbling around me. I needed to act, and that Battle of the Year VHS tape was my lighthouse in the fog. It bellowed for me in the mist, emanating from Jerry's VCR player. I booked it from my house to make the trek across town to the mobile court.

Walking in a small town in the encroaching dusk is a spiritual experience. It fills your mind with wonder. Floods it with thoughts and insight in the solitude. More than anywhere else or any other time, I am most like myself walking in the twilight of my hometown.

Before I knew it, as if I had stepped outside my house and directly onto the front porch of Jerry's mobile home, I was there. I knocked on the door while slipping off my shoes, adding them to the ever-present pile of shoes at the entrance to their home. Jerry's mom popped open the door before I could count the pairs.

"Aw, good. You eat too. Come, come," Jerry's mom said while ushering me inside. Jerry's parents never said hello but always welcomed me into their home. His mom pulled me into the kitchen and thrust a plate into my hands. Before I knew it, my plate accumulated fried fish, a baggie of sticky rice, and sauce to go with the sticky rice. I thought it strange that the sauce smelled fishier than the actual fish. I thanked Jerry's mom and nodded at the dad of the household.

I found Jerry tucked away in the corner of his room at his new computer. That was a thing. That was the thing back then. This was around the time when computers were finally accessible to poorer folks like us. It felt like how you imagine families felt in the '50s, when they would crowd around the unveiling of a television. Our families could afford these big boxy Compaq or Dell computers. These off-white heavy machines were our access to a world outside West Liberty.

"Long time, no see!" Jerry said, craning his neck from his computer screen and back.

He was right. I hadn't seen Jerry much since my fallout with Ruben. Out of all my old friends, he was the only one I kept in touch with, but it was only sporadically, and mostly over our shared interest in dance. Over his shoulder the fuzzy monitor shone back at me, displaying a rudimentary logo my friend was working on. He was nudging an M so it fit above a W in MS Paint. "I think that's it. That's the one. The official Midwest Breakaz logo," Jerry said while he admired his work.

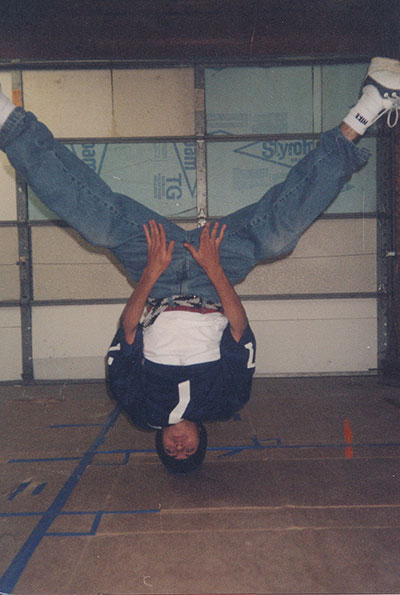

PHOTO COURTESY CHUY RENTERIA

Chuy Renteria as a

teenager practicing

his dance moves on

cardboard laid out in his

family's garage.

PHOTO COURTESY CHUY RENTERIA

Chuy Renteria as a

teenager practicing

his dance moves on

cardboard laid out in his

family's garage.

I let out a low whistle as I unwrapped the baggie of sticky rice on my plate. "That looks sweet," I said after my first bite of rice. Jerry nodded. The Midwest Breakaz was the name the Laotians had given their breaking crew.

"Bro!" Jerry said with exaggerated gusto as he noticed me eating. "How many times I gotta tell you. You can't be just eating the sticky rice by itself. It's weird. At least eat it with the jeow! That's what it's there for." He was talking about the sauce nestled between the rice and fish, but it was too late.

I gulped down a mouthful of rice before smiling back. "I can't help it. It's too good on its own."

Jerry rolled his eyes and got back to the Midwest Breakaz logo. It happened in a flash, how all the Laotians in West Liberty got into breakdancing, as they called it. All of a sudden they knew how to do these incredible spins and flips. They learned the moves the way other trends and fads and cultures managed to find their way to our small town— through cousins on the coast. Jack and Randy Lovan were the best of the group, and they learned from their cousins out in California. They would go on summer vacations and soak up as much knowledge as they could, then come back to town and teach all the other Asians. They would practice their moves in their yards at the trailer court or in the carpeted basements of their uncles' houses.

"Anyways, this is what you wanted, right? Battle of the Year '97, boy! Be sure you make it all the way to the end for the battles. That's when things get real crazy."

I exchanged the plate of uneaten food for the tape, cradling it in my palms like it was a vessel of pure energy.

"So that's it? You're gonna start breaking?" Jerry asked.

"Yeah. I'm going to run home, watch this for inspiration, and start right after."

"Okay, okay, that sounds like a plan," Jerry said, ripping off a piece of fish on the plate with his fingers. "Why all of a sudden now though?"

I told him all the gory details of how Cheryl had her friend April break up with me over the phone. April lived in the mobile home next to Jerry. At this bombshell he got up and peeked through his blinds as if to check that they weren't currently plotting against us.

Jerry got it after I finished telling him the story. He had a first-row seat to all the drama with our old friend group and knew how much I was twisting in the wind without them. "This will be good for you, man. Breakdancing is the s---. You get a move and you feel like you're the king of the world. You should get going so you can get some good practice in."

I thanked Jerry for the tape and got up to leave. There was something bubbling out of me though, something I couldn't help but ask. "What are your plans for tonight?"

It was a cool Saturday night in the middle of summer. The races would soon be roaring. A perfect night for hanging out at the Shack. Jerry took a second to gather a response. "You know. The same ole, same ole."

"Gotcha," I said before giving the Midwest Breakaz logo one last glance.

The words came out of Jerry in soft, rapid succession, like they were too real and precious for him to speak in a regular cadence: "You know, Ruben's been asking about you. We all have, man. We miss you. He's sorry. You should come hang with us sometime when you're not breaking."

It was the last thing I wanted to hear. I had already made one life-altering decision in getting this tape. Forgiveness and reconciliation were too much to pile on top of that.

"Yeah. I should sometime," I said before giving Jerry dap and peacing out. Jerry's mom smiled at me while the men held their poses at the table.

After putting my shoes on, I started to run home. It was like I was sprinting in a race with the VHS tape as my baton. I was trying to outrun the last things Jerry said, about Ruben being sorry. I didn't care if he was sorry. I wasn't ready to forgive him. Or to say sorry myself. I ran so fast it felt like my lungs would burst. It was getting to be nighttime and my feet were a blur in the fading light. I gasped for breath, doubled over on my front porch. No time to rest too much. I fought through the sting in my throat and went inside to my room.

Soon the old Battle of the Year '97 tape was playing on my television. All its past owners had played and replayed the tape many times and the footage was fuzzy as a result. It didn't matter. The garbled footage had my full attention. Battle of the Year is a breaking event held in Germany every year. The event invites breaking crews from all over the world to perform showcases. A panel of judges picks the top four crews to compete against each other for first and second place. The tape was a two-hour document of the best showcases and those top battles. I sat and watched the entire tape, showcase after showcase, battle after battle. I noted the different styles of the groups from Europe compared with those from Africa or Japan. I rewound particularly impressive moves and freezes, which most of them were to me.

In a simplistic way, you can break down breaking into two camps: the power heads and the style heads. Power is what most people think of when they think of breaking. It's the spinning moves—headspins and windmills. The moves flashed in music videos. The stuff most impressive to people who don't know anything about the dance. The Laotians in the trailer park dedicated their training almost exclusively to power moves. A lot of times they would take off their shoes and practice their power moves in socks to make it easier.

In contrast is style. Practitioners of style concern themselves with footwork and musicality. The best way to describe footwork is staccato movement low to the ground. It's when you're stepping around on the floor on your hands and feet. Good footworkers take traditional steps like the six-step and Russian taps and piece them together in creative ways. Of course, categorizing breaking into these two camps is an oversimplification. A good all-around breaker takes elements of everything, transitioning from power moves to freezes to footwork as a complete package. That's not even to get into the discussion of power heads who are able to do their power moves in creative and stylistic ways.

The majority of crews on the Battle of the Year tape concerned themselves with power. In the early to mid-'90s there was a wane in the breaking scene stateside. I'm careful not to say that it died in America. Th ere were still very active scenes on the coasts and in bigger Midwestern cities like Chicago. But that huge explosion of dancers in the '80s, the one that infiltrated the suburbs and small towns, had dissipated. Before the Asians started trying swipes and headspins in town, I had never seen anyone move like that in person. But while the dance faded in the American consciousness, it picked up steam around the world. The mid-'90s saw a surge of dancers everywhere from France, Russia, and the Netherlands to Japan, South Korea, and China. The worldwide representation was immediately clear in the diversity of crews on the tape. But for the most part they danced alike, with that power focus. At the time I, of course, had no clue about the intricacies of power versus style. All I knew was that everything changed when the sole U.S. crew started to dance: Style Elements.

Style Elements. They deserve their own paragraph in this book. For their impact on the worldwide dance scene. For their impact on me. It was immediately clear that they were different. True to their name, they had style. They were unique and creative. All the other crews danced to the same type of funk or electro beats. Style Elements started their showcase to the sounds of machine-gun fire and warfare. They pantomimed being soldiers, crawling on their bellies to get to their marks on the floor. This was weird and different. It was theatrical. From there they took turns dancing to the soft guitar opening of Metallica's "Enter Sandman." I watched the rest of their showcase in silence. They were lightyears ahead of anyone else sharing that stage. Their movement was more complicated and bombastic. Style Elements got best showcase and won their battle for first place. It was no contest. While watching I felt a weird sense of pride that these American dancers went to Germany and stood out against the rest of the world. I felt this connection and representation. Style Elements hailed from Southern California, and even though I was so removed from them, I felt connected. It was the first time I felt something like patriotism. I smiled at this thought while I grabbed a sweater.

There was nothing left to do. I had to try something. There was too much inspiration and energy pulsing through my body. By then it was well into the night. I walked outside into the now cool summer air. A flat spot in the backyard by our old swing set made an adequate spot to try my moves.

My "moves." Despite all my watching of the Midwest Breakaz across town, I hadn't done any dancing of my own. I had no moves to try. I did what I could think of. I flopped around in the silence of the backyard. No handstand or cartwheel was safe. I revisited all manner of basic somersaults and elementary school tumbling maneuvers. I could smell the grass stains accumulating on my sweater. Every once in a while I would need to wipe the dew off my hands.

I imagine it must have looked a sight, this boy trying to walk on his hands and spin on his back in the grass in the dead of the night. I didn't care. This exciting feeling filled my lungs. Filled my every breath. I fell out of a particularly daring maneuver, landing on my back in the soft yard. The night sky loomed overhead as I sprawled on my back, my arms outstretched toward the heavens. Our town was small and insignificant enough that there wasn't enough light pollution to dilute the radiance of the stars. My breath labored as my chest rose and fell in time with my exhalations. The air was cool but humid, a combination that made clouds of breath materialize every time I exhaled. Each inhalation stung as I got back onto my feet. It didn't matter. Nothing else mattered. I got up and kept trying every move I could think of. I haven't stopped since.

© 2021 Chuy Renteria. Used with permission from University of Iowa Press.