IOWA Magazine | 09-21-2021

How Two Daring UI Students Uncovered Iowa's Greatest Cave

By Josh O'Leary

4 minute read

Fifty years ago, a pair of amateur cave divers discovered and mapped what proved to be the largest cave in the upper Midwest.

PHOTO: DAVID JAGNOW

Steve Barnett (left) and Dave Jagnow (right) are pictured with fellow caver and Iowa Grotto member Tom Egert in their cave diving gear in April 1968.

PHOTO: DAVID JAGNOW

Steve Barnett (left) and Dave Jagnow (right) are pictured with fellow caver and Iowa Grotto member Tom Egert in their cave diving gear in April 1968.

In September 1967, two University of Iowa students made a thrilling geologic discovery.

Amateur cave enthusiasts David Jagnow (70BA) and Steve Barnett (87BS) began exploring the Driftless area along the Mississippi River—a region untouched by the glaciations that flattened much of the Midwest in the last Ice Age—while studying geology at Iowa. Intrigued by a rumor of a cave in northeast Iowa used by bootleggers during Prohibition, the duo traveled that fall to the Coldwater Creek Conservation Area in Winneshiek County.

Wearing blue jeans, a sweatshirt, and tennis shoes—but no safety line—Barnett dove into the frigid Coldwater Spring, then swam beneath a jutting cliff that, as legend had it, housed the bootleggers’ cave. On his second free-dive attempt, Barnett became disoriented under the cliff. Thinking he was swimming back to the surface, Barnett instead emerged in “a room as big as a barn,” as he later described the cave. There, he spotted something even more intriguing: an underwater passage about 10 feet in diameter leading further beneath the hills feeding the spring.

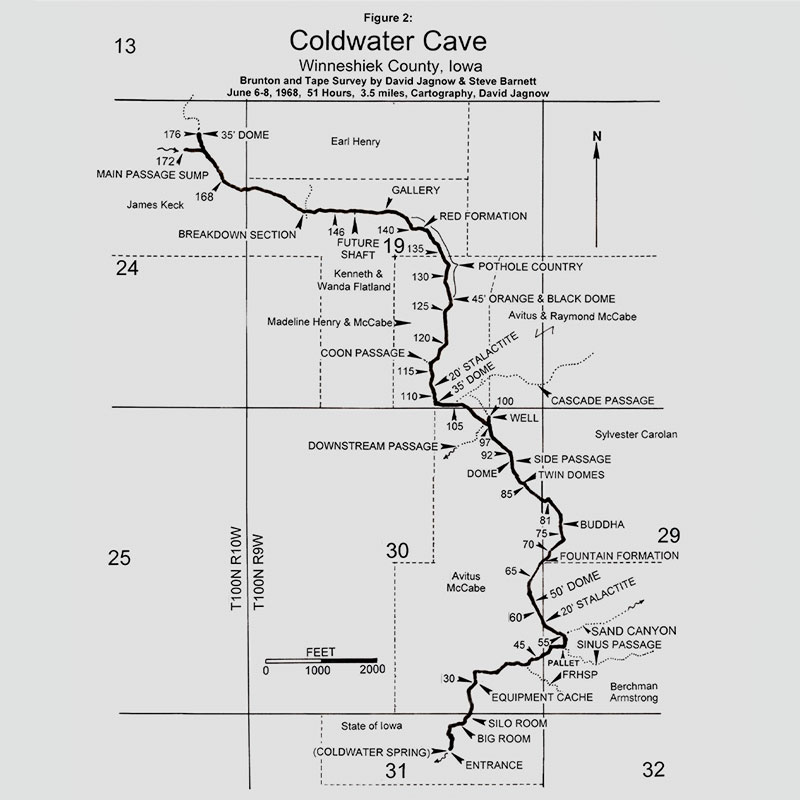

Barnett and Jagnow returned to Iowa City, where they ordered diving equipment and trained with scuba gear at the Mayflower Apartments pool. In February 1968, the explorers returned to Coldwater Spring, this time prepared for their first cave dive. The expedition, which lasted 1½ hours and took them through the underwater passage and 260 feet into the cave system, was just the beginning. Over the next three years the spelunkers would make 24 journeys into the depths of Coldwater Cave beneath Iowa’s hills and farmland, accompanied by fellow members of the Iowa Grotto, a local chapter of the National Speleological Society.

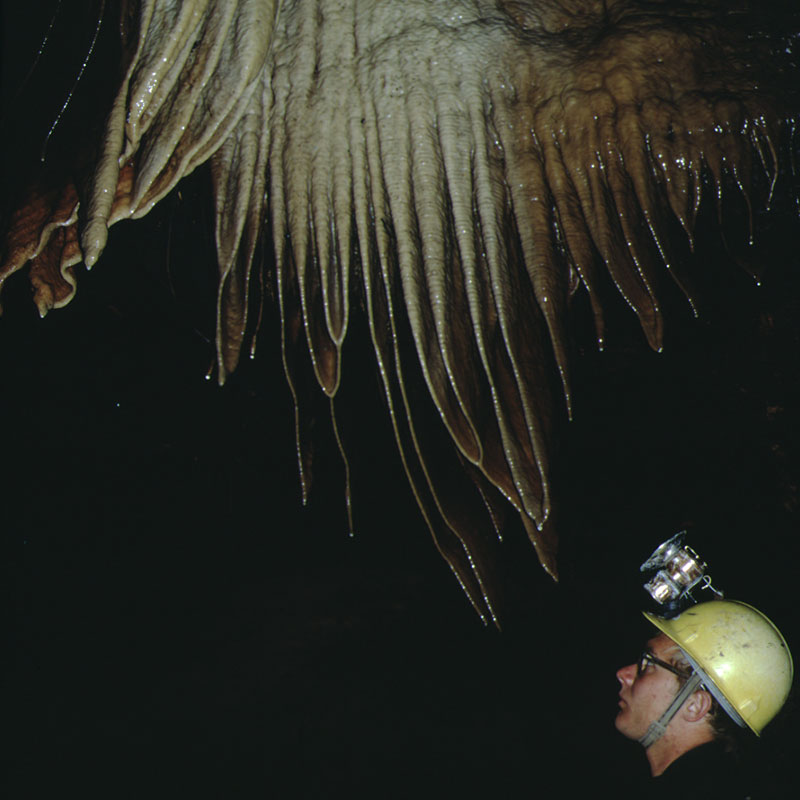

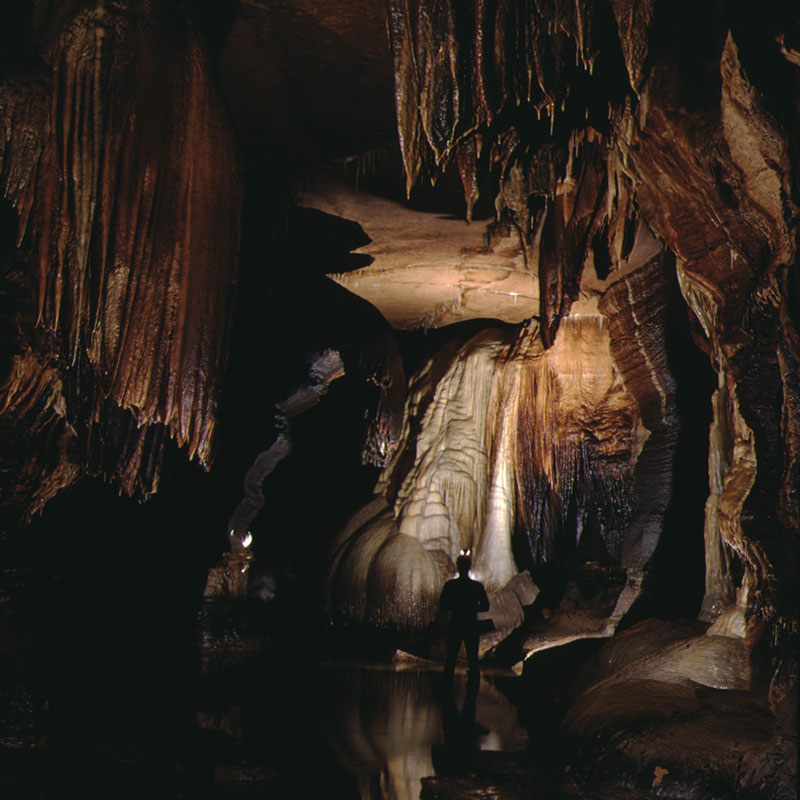

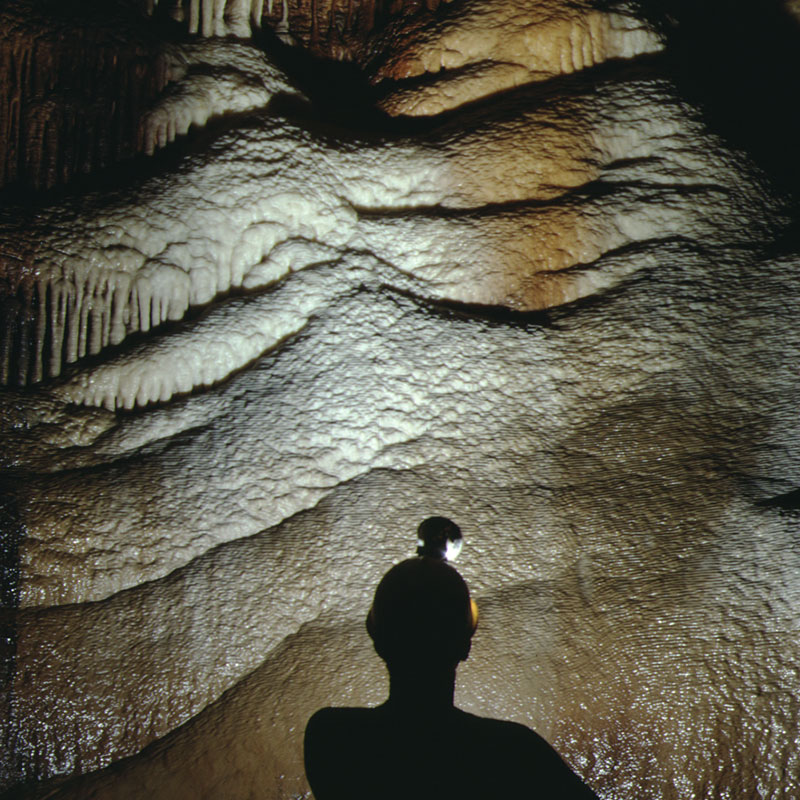

Barnett and Jagnow ultimately surveyed 3.5 miles of stream passage and worked with the state to preserve and protect the cave. Squirming through narrow underwater channels, splashing through pitch-black corridors, and enduring bone-chilling temperatures, they discovered a complex system of massive rooms, towering domes, and spectacular rock formations that cavers like to call “pretties.”

They also found ancient fossils, swimming trout, and other tiny underground creatures. “We were the first to explore this unseen world, and we felt a responsibility to protect it,” Jagnow says in a 2018 book he wrote with Barnett titled A World Below: The Underwater Discovery and Exploration of Coldwater Cave. “We wanted to prevent diving clubs and other cavers from risking their lives in the cave, but we also wanted to preserve its fragile beauty and environment.”

The entrance to the cave was gated off by cavers in the early 1970s, and the Iowa Geological Survey drilled a shaft into the upper reaches of the cavern to allow for easier and safer access. Coldwater Cave was declared a national natural landmark in 1987, and experts building on Jagnow and Barnett’s early work have since surveyed 17 miles of passages. Coldwater Cave is said to be the largest and longest cave discovered in the Upper Midwest and the 45th largest in the U.S.

After graduating from Iowa, Jagnow earned a master’s degree at the University of New Mexico and worked professionally as a geologist while continuing to explore caves across the U.S., Mexico, and China. Meanwhile, Barnett, who completed a UI degree in geology in 1987, surveyed caves as far as the Maya Mountains in Guatemala and Belize.

“I have never found another caving partner who was so complementary to my own enthusiasm and skills, and I attribute the success of our caving discoveries to the efficacy of the partnership we shared,” Barnett says of Jagnow in their book. “Had we not found one another and bonded as a team, Coldwater Cave might still be unknown today.”

Iowa Public Television’s Iowa Outdoors goes inside Coldwater Cave.

Join our email list

Get the latest news and information for alumni, fans, and friends of the University of Iowa.

Join our email list

Get the latest news and information for alumni, fans, and friends of the University of Iowa.