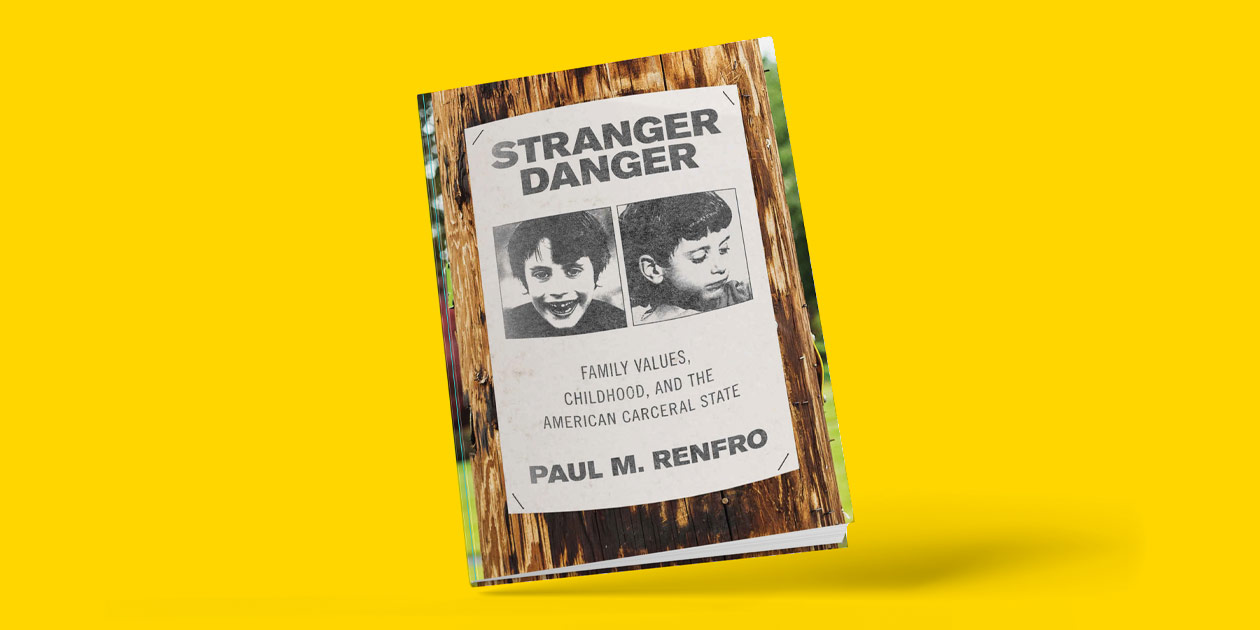

Iowa History Grad Writes Book on Stranger Danger

Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American

Carceral State by Paul M. Renfro (16PhD),

Oxford University Press, 312 pp.

Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American

Carceral State by Paul M. Renfro (16PhD),

Oxford University Press, 312 pp.

Like many kids of his generation, historian Paul Renfro (16PhD) grew up being warned about the threat of strangers. High-profile cases like the disappearance of Iowa paperboys Johnny Gosch and Eugene Wade Martin in the 1980s served as cautionary tales nationally, including in Renfro's home state of Texas. At the breakfast table, the faces of abducted children on milk cartons were a constant reminder to stay vigilant. "It took me a while to disabuse myself of the notion that everyone was out to get me," Renfro says.

PHOTO COURTESY PAUL M. RENFRO

Paul Renfro

PHOTO COURTESY PAUL M. RENFRO

Paul Renfro

In his newly published book, Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American Carceral State, Renfro examines the child kidnapping panic of the late 20th century through an academic lens. Renfro became fascinated by the topic when he arrived at the University of Iowa as a PhD student. There, he learned about the 2012 kidnapping and murder of two young girls in Evansdale, Iowa—Elizabeth Collins and Lyric Cook-Morrissey—and how the case stirred Iowans' memories of the paperboy abductions three decades earlier. Intrigued, Renfro spent several years writing his dissertation on the subject, which he adapted into a new book.

Iowa Magazine recently caught up with Renfro, an assistant professor of history at Florida State University, to discuss Stranger Danger.

How did the "stranger danger" panic emerge, and what was the impact?

Amid tremendous economic uncertainty, political instability, and social upheaval in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a slew of high-profile cases of missing children brought national attention to matters of child protection. Bereaved parents, policymakers from across the political spectrum, and a receptive news media alerted the public to a perceived epidemic in stranger kidnappings. Some individuals insisted that as many as 50,000 young Americans fell victim to stranger abduction in any given year, although the figure was (and remains) somewhere between 100 and 300.

A moral panic took hold and amplified calls to "get tough" on crime. Few American policymakers or media figures seemed willing to challenge the "stranger danger" scare. On the contrary, Republicans and Democrats alike stoked the panic, helping to build and expand a legal and cultural infrastructure designed to keep kids safe from strangers—even though children are far more likely to be exploited or harmed by family members or acquaintances.

Looking back, were those fears of random abductions justified?

Stranger kidnappings do occur in the U.S., and the cases of Adam Walsh, Johnny Gosch, Eugene Martin, and others are incredibly tragic. But these sorts of abductions are extremely rare. Children are much more likely to be victimized by a family member or acquaintance, and they face far graver, less sensational threats daily: hunger, poverty, car accidents, illness, etc. Rather than marshaling significant resources toward addressing the perceived "stranger danger" threat, Americans should focus on improving the structural conditions that harm millions of children and families.

How did the paperboy disappearances in Iowa affect the national climate of child safety?

Most notably, Gosch and Martin became the first missing children to appear on milk cartons. Anderson Erickson Dairy in Des Moines launched the campaign shortly after Martin's disappearance in 1984, and milk processors with wider distribution networks soon adopted the practice. Although the campaign proved largely unsuccessful, since it failed to bring many children home, literally billions of such milk cartons were distributed globally, and the practice lives on in popular culture.

The Gosch and Martin cases garnered national attention, I argue, because these boys carried many of the markers of idealized American childhood. They were white, middle-class, Midwestern paperboys, and their disappearances seemed to suggest that something was terribly "wrong in a place that's supposed to be so right," in the words of Des Moines Register editor James P. Gannon.