The Art of Collecting

John Pappajohn had been talking auctions, acquisitions, and Andy Warhol for a good part of the morning when his assistant asked him if he had a moment to take a call. The businessman picked up a phone outside the conference room at the Financial Center in Des Moines—the downtown high-rise where he still works seven days a week, decades past the age when many retire to balmier climes.

PHOTO: BRIAN SMALE

PHOTO: BRIAN SMALE

"I want to buy the piece," Pappajohn (52BS, 10LHD) told the person on the other end of the line. He paused a second, listening. "No, we have to do it in dollars." Then, before hanging up a minute later: "We have a deal, OK?"

Few have closed more deals than Pappajohn, who has financed more than 100 startups and taken nearly 50 companies public since launching one of the nation's earliest venture capital firms in 1969. But some of his biggest acquisitions have had nothing to do with finance. As Pappajohn built his business empire, he and his wife, Mary, assembled an art collection that would be the envy of most museums. With a love of contemporary painting and sculpture, the couple has been a fixture at New York auctions and made ARTnews magazine's list of the top 200 collectors in the world each year from 1998 to 2014.

This morning's phone call finalized the Pappajohns' latest major acquisition—though it wasn't heading to one of their art-filled homes in Des Moines, south Florida, or New York's Fifth Avenue. The caller, Pappajohn explained as he settled back into his chair, was a Berlin dealer representing a renowned international sculptor. They'd just reached an agreement for the latest addition to the Pappajohn Sculpture Park—a 4.4-acre art garden just a few blocks away filled with works he and Mary have donated to the Des Moines Art Center, many of which previously stood in their front lawn. Pappajohn wasn't yet ready to publicly name the new sculpture or its artist, but it will be the 30th piece installed in the popular park since its opening in 2009.

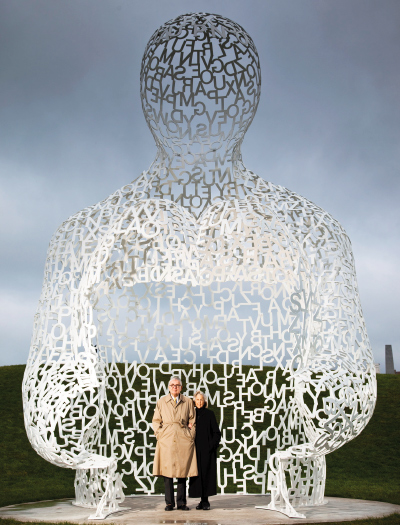

PHOTO: BRIAN SMALE

The John

and Mary

Pappajohn

Sculpture Park

and its iconic

piece Nomade

(above) is a

Des Moines

landmark.

PHOTO: BRIAN SMALE

The John

and Mary

Pappajohn

Sculpture Park

and its iconic

piece Nomade

(above) is a

Des Moines

landmark.

Des Moines isn't the only location to benefit from the couple's love of art. Last year, at his alma mater University of Iowa—where two buildings, a hospital pavilion, and several centers and institutes already bear the Pappajohn name—he added two new landmark sculptures. Commissioned from American artist Deborah Butterfield, a pair of larger-than-life bronze horses now greet visitors in the John and Mary Pappajohn Plaza outside the new UI Stead Family Children's Hospital.

Beyond Iowa, the Pappajohns are deeply involved in a number of prominent museums. John is currently vice chair at the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum and serves on the trustee council for the National Gallery of Art, while Mary has served on the board for the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and is active with the Des Moines Art Center. This past spring, the couple helped fund an exhibition at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art featuring Iowa icon and former UI faculty member Grant Wood.

In his office surrounded by artwork and art books, Pappajohn spoke with Iowa Magazine about his first purchase, how he uses his business savvy to land the best pieces at exhibitions, and why he has no plans to slow down after turning 90 in July. Here are the highlights of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

“My incentive isn’t to be rich; it’s to do what I want in philanthropy. Mary and I feel strongly that a successful life must include service to society and our fellow man.” —John Pappajohn

What first sparked your interest in art?

I graduated from Iowa in 1952, and I wanted an easy course my senior year, so I took History and Appreciation of Art. Now I'm an immigrant; I was never in a museum. We didn't have a museum in Mason City, where I grew up. But I had an amazing professor at Iowa for the History and Appreciation of Art. He was exciting. When I saw the impressionists, I said, "I've never seen anything like this before."

I went out and started to make a living in insurance and got married about that same time. My wife, Mary, had a degree in related arts from the University of Minnesota. The first month we were married, we went for a walk in Des Moines and walked into an art gallery. We bought a print for $50, and that was the beginning of our art collection.

What was the print?

The name of it was The Resurrection, and it was by Keith Achepohl (60MFA), who was an artist at the University of Iowa. We still have it. It's a symbol of whence we came, and we still like it. It's in Florida and on the wall—we'd never sell it. It's going down with us.

How did that first piece evolve into the collection you have today?

Mary and I started going to the Des Moines Art Center, and we liked the art. Later as a venture capitalist, I got lucky and I made some money and we started buying art, and they invited me to join the board of the Des Moines Art Center. The director was James Demetrion, who had a world-class reputation for being able to pick out the best art in a group of paintings. For instance, Des Moines owns the most famous Francis Bacon painting of the pope. It's the best in the world. He chased that painting for years until he got it.

I was a very active venture capitalist and I helped organize and fund a health care company, Caremark, and it was a screaming success. I made many millions, and Mary and I became much more aggressive with our art purchases. We made many trips to New York to visit galleries and dealers, including Christie's and Sotheby's. We developed a good relationship with dealers, which is very important.

I once went to a show in New York and the artist was Gerhard Richter, and it was his first show in America. The gallery was Marian Goodman, and I went to that show with James Demetrion. I remember the paintings were $18,000. I picked out one, and Jim picked out one.

It was a memorable purchase because a month after I bought it, the dealer called and said, "Mr. Pappajohn, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston had a hold on your painting, but didn't have the money to buy it and had released it. Now they've raised the $18,000, and they'd like to own the painting." So I said they can have it because it's a museum. That painting today is worth many millions.

But as a result, Mary and I ended up buying another Richter painting from his dealer. She sold us her own painting, a large diptych, because she was moving from downtown to midtown Manhattan, and the diptych was too large for her apartment and wouldn't fit. We bought it for $60,000, and I eventually ended up selling it; it set a world record at the time. But that painting is worth four times as much today. This is the history of what's going on in the art market.

When you were buying art early on, did you see it as an investment?

Absolutely not. I keep track of art prices because I'm a businessman and I follow trends, and I think they're obscene today. I don't know much about new art and wonder if it is even going to survive. It's interesting because there are many young artists today that are selling for multimillions. You can go back through history to find artists that were selling for a lot of money that don't have much value today. Art is faddy.

The New York Times had a recent story about how all of a sudden art has become a status—people are buying to say they own art, which is unfortunate because people are maybe buying art for the wrong reason. But that's for everybody to decide for themselves.

Collecting is more personal for you?

Yes, it is. We never imagined art would increase in value—that isn't why we bought it. We have over 300 pieces. We have art in Des Moines, we've loaned to museums, we've gifted to museums. We've given pieces to the Whitney, the Guggenheim, the National Gallery, and the Walker. We've given much to the Des Moines Art Center, including 30 sculptures to the museum and the city of Des Moines to establish the John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park. Mary and I are very proud of this project.

We just gave a sculpture to the National Gallery. They had a show for an artist named Anne Truitt, and they said our piece was very important to their collection, so we gave it to them.

We own Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol. We bought art whenever we had a little extra cash, and because I was a venture capitalist, I was going to New York all the time. In fact, an agent with United Airlines once asked me, "Mr. Pappajohn, how come you go to New York all the time?" I said, "Don't tell anybody, but that's where the money is."

PHOTO: BRIAN SMALE

PHOTO: BRIAN SMALE

What was your first major purchase?

Mary and I bought a Mark Rothko painting at auction, and I remember at that time it was a million-dollar purchase. We ended up selling it for many millions. We didn't intend to sell it, but there was someone who wanted to buy it in New York, so we shipped it to Sotheby's. It was a 1969 painting, which was the year Rothko committed suicide, so it was a very important piece. I probably used some of that money for my investments, then I turned around and used the investment returns to buy more art. It's whatever works; being an entrepreneur and businessman, I'm able to mix and match fairly well.

How do your business smarts help you in the art world?

Sometimes when you go to a show, there are 20 paintings by an artist, but the best painting is usually saved for museums. Those paintings are the real collector pieces. So I would tell the dealer, "I brought a blank check with me. If you save it for a museum, it may take 60 or 90 days, and they may turn it down." So what I was doing was using that tactic for getting the best art. I wrote them a check on the spot, and it worked most of the time, and we got first pick. I combined a little bit of business and art. And the museums will eventually get most of our art anyway.

What do you enjoy most about collecting?

Mary and I are passionate collectors and relate to the art we acquire. It's exciting to view our art in our home.

There's also a do-gooder aspect to collecting and gifting. Did you know that David Rockefeller sold his art collection at auction recently? He sold it, put the dollars in a foundation, and it's all going to go to social causes. It's wonderful. David Rockefeller! I've noticed at auction in the last year that several other major collections have been sold, and it's all going into family foundations for social causes.

Can you tell me the story behind the horse sculptures you donated outside UI Stead Family Children's Hospital?

The artist is Deborah Butterfield. Mary and I became friendly with her and we like her work, and in the sculpture park here in Des Moines we have two Butterfield horses. So when Dr. Jean Robillard was building the children's hospital, we wanted to do something. These are bronze sculptures, so the kids can jump on them and do anything they want without hurting them. We thought they were very appropriate, so we worked out a gift. We think they've been terrific.

PHOTO: WILL RAGOZZINO/BFA.COM In 2013, the Pappajohns were honored by

Americans for the Arts at the National Arts

Awards in New York. They accepted the Eli and

Edythe Broad Award for Philanthropy in the Arts.

PHOTO: WILL RAGOZZINO/BFA.COM In 2013, the Pappajohns were honored by

Americans for the Arts at the National Arts

Awards in New York. They accepted the Eli and

Edythe Broad Award for Philanthropy in the Arts.

Turning 90, do you think about the legacy you're leaving for future generations?

That's very interesting—what's the important part of legacy? That's the real question. What are we going to be remembered for? Maybe philanthropy, and Mary and I are going to do a lot more of that, because that's the future. Maybe entrepreneurship. There are 270,000 college students who have taken entrepreneurial courses (through the Pappajohn entrepreneurial centers at five Iowa universities and colleges, including the UI). We get so many letters from students who say, "You changed my life." As technology continues to evolve, the centers will continue to develop more innovation and contribute even more to society and the economy. I also emphasize PMA—positive mental attitude.

I was an entrepreneur from the time I was born. I was a rag merchant. I collected brass, copper, and steel at the city dump, and I used to sell it to the scrapyard. As a kid I'd take two gunny sacks to the scrap dealer every day. He liked me and took me to the bank and got me my first letter of credit. That's the immigrant part—we try harder.

I tell students that with any job, you learn from everything you do. Even shoveling manure you learn something. I did whatever I could to save money. It took me six years to graduate from college at Iowa because I took turns going to school and working with my brothers. But I had $2,000 in the bank and had no debt when I graduated. I worked at Brady's supermarket in Iowa City every morning, every lunch, after school. I was making $2 an hour almost full-time. I never went to an Iowa football game because I worked every Saturday, and I'm a real Iowa football fan. You do what you have to do.

You haven't slowed down much since.

I never anticipated being 90. I work seven days a week. I'm in my office every Saturday and Sunday. Mary is a very understanding wife, and when she calls, I go home. But I'm very active in my venture business, and I'm doing very exciting things. My incentive isn't to be rich; it's to do what I want in philanthropy. Mary and I feel strongly that a successful life must include service to society and our fellow man. This is how we will be judged. We must all try to make a difference in this world.