An Artist's Eye

In 2016, comic book artist Phil Hester (88BFA) began a new series called Shipwreck at his home studio in North English, Iowa. Surrounded by shelves packed with superhero anthologies, caped action figures, and awards spanning a prolific career, he sketched the story of a scientist who survives a mysterious crash and is marooned in a nightmarish new world.

Hester could relate. For more than 30 years, he had illustrated some of the biggest names in comics—Green Arrow, Batman, and nearly every other masked hero in the DC and Marvel universes. But now, his shades drawn and lights dimmed, the blue-eyed artist squinted at his drawing board as if through a fog. Just as Shipwreck’s hero, Dr. Jonathon Shipwright, was trapped in a surreal universe, Hester’s world was increasingly unrecognizable.

A year earlier, Hester had been diagnosed with congestive heart failure and made strides to turn his health around. He stopped working until all hours of the night, made time to exercise, and shed 75 pounds. Then, confoundingly, another part of his body began to fail him. A progressive eye disease known as Fuchs’ dystrophy had laid siege to his vision—each day hazier than the last. It distorted his eyesight and made bright light excruciating. Work became an agonizing chore. For Hester, a future without art—and the means to provide for his family—was in many ways more frightening than his heart scare.

“I could deal with the mortal peril a lot better than I could deal with losing my ability to draw,” Hester says. “Everybody dies, and we all have to figure that out and deal with it. But losing how I define myself was more terrifying. You feel really helpless and at the mercy of this disease.”

If Hester’s life was a comic book storyline, Fuchs’ dystrophy was his kryptonite. But a superteam would soon assemble in his corner—doctors at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, transplant specialists at the Iowa Lions Eye Bank, and two anonymous donors who would inspire Hester on a new crusade.

Hester spent much of his childhood in North English—a farm town about 35 miles southwest of Iowa City that makes Smallville look like Metropolis. But for a time when he was in elementary school, Hester’s family followed his father’s work around the country. It was a chaotic period marked by new cities each year, new schools, and few chances to make lasting friends. Hester instead found comfort in the pages of his comic books. His favorite superhero was Spider-Man, an awkward high school kid with hidden powers and a secret life.

As voraciously as Hester read comics, he also loved to draw them. One day after finishing the latest Iron Man, 12-year-old Phil felt particularly inspired. The comic ended in a cliffhanger: Tony Stark plummeting to the earth without his Iron Man suit after villains tossed him off a flying fortress called the Helicarrier. Unable to wait for next month’s issue, Hester sharpened his pencil and set to work on his own conclusion. When he finished, Iron Man had once again escaped the clutches of death, and a thought bubble appeared over the head of the young artist: “The people who actually do this for a living, this is what they do—they just make it up. I can do that, too.”

After his parents divorced, Hester returned to North English but found comics hard to come by in rural Iowa. A driver’s license meant weekly trips to the Rexall drug store in Sigourney for DC titles and Star Drug in Williamsburg for Marvel. Hester graduated from high school aspiring to be a professional cartoonist but knowing he needed to improve his chops as a draftsman, so he enrolled as an art student at the nearby University of Iowa.

For our cover story on the world of tomorrow, renowned comic book artist Phil Hester (88BFA) imagines a futuristic Pentacrest featuring Hawkeyes on hoverboards. Hester recently returned to the UI School of Art and Art History to sketch the cover and share how his time at the university helped shape his career.

In those days, recalls Hester, there was a wide chasm between the fine arts and commercial arts. While universities today have courses dedicated to comics and graphic novels, in the mid-1980s, there were no such options. Hester arrived at his first class with a couple No. 2 pencils and a love of Frank Frazetta, who painted the covers of some of his favorite fantasy novels and heavy metal records. By his senior year, Hester had experimented with paints, charcoal, and sculpture, and his favorite artist was Mark Rothko, the midcentury abstract expressionist.

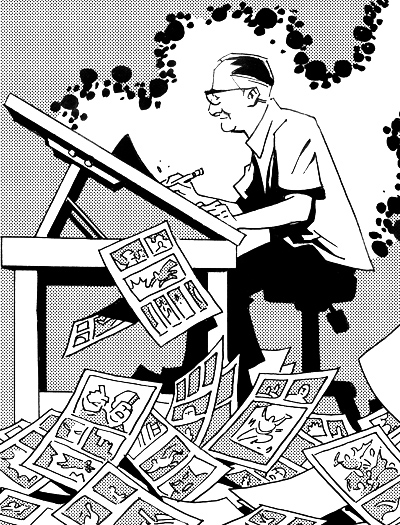

In between classes, Hester worked as an editorial cartoonist for the Daily Iowan—his first paid gig—and studied under longtime UI art professor Joe Patrick, whose life-drawing lessons would later provide Hester with a deep toolbox as a comic artist. “Drawing from a model for three hours a day helped me develop this vocabulary of the human face and figure in my mind,” says Hester about his time in art school. “It broadened my horizons. One of the things about comics is most of your work is self-generated, which is kind of a fine distinction I make to other artists. We don’t have time to use a lot of reference, and that means you can’t really have a model pose for you and reference everything you want to draw.”

Though it’s been 30 years, Patrick, who is now retired, says Hester made an impression with his enthusiasm, openness to new ideas, and willingness to take chances. “Although I had too many classes and too many students to recall them all, some do stand out,” says Patrick. “Phil is among those, perhaps because his manner was individualistic, self-motivated, and self-directed. He seemed to have a clear personal objective for his art. But that did not stand in the way of his being receptive to gaining the benefits that perceptual observation in drawing would provide.”

In the mid-1980s, independent publishers took the comic market by storm thanks to the phenomenon of Mirage Studios’ Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Hoping to emulate Mirage’s success, countless small comic makers sprung up overnight and opened the door for young talent like Hester, who was able to land low-paying work even as a student. After college, Hester worked at a small-town Iowa newspaper, the Knoxville Journal-Express, and at night he’d hunker down at a drawing table wedged between his washer and dryer.

Hester’s big break came in his mid-20s at a comic book convention in Kansas City. He’d been sending samples to the major publishers since he was in high school, but on the floor of the convention, he showed his portfolio to a Marvel editor who liked what he saw. On a whim, the editor handed Hester a script for the Sub-Mariner series. That assignment led to work from publishers like Dark Horse and First Comics, then the occasional big-league job from DC and Marvel. In 1993, DC commissioned him for Swamp Thing—a half-human, half-plant creature that was among Hester’s favorites as a kid.

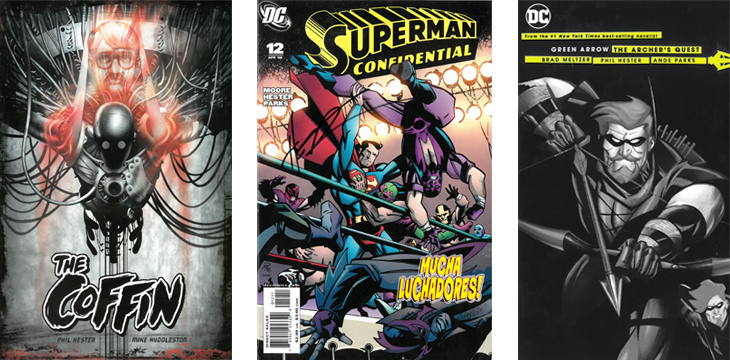

UI art school graduate

Phil Hester has illustrated

and written stories for

some of the biggest

names in the comic book

universe, including Green

Arrow and Superman,

as well as creating cult

classics like The Coffin.

UI art school graduate

Phil Hester has illustrated

and written stories for

some of the biggest

names in the comic book

universe, including Green

Arrow and Superman,

as well as creating cult

classics like The Coffin.

“I probably wasn’t ready for that assignment, but I didn’t care,” Hester says of his first extended run on a major series. “It was like being called up by your favorite baseball team and knowing you’re terrible. I’m the worst centerfielder ever to be playing for the Red Sox. But I’m playing for the Red Sox.”

After three years of illustrating Swamp Thing, Hester had arrived—a rare Midwest talent in a coastal-centric industry. His bold style and keen eye for composition set him apart, and he became known for his angular, chiseled characters and panels drenched in heavy shadow. In the coming decades, Hester brought to life some of the industry’s most iconic superheroes: the Incredible Hulk, Wonder Woman, and the Man of Steel.

“Even at this age, I’ll be drawing Superman and I’ll stop and think that for some kid, somewhere—like in Iowa—this will be the first time he sees Superman,” says Hester, who spends about half his time these days writing scripts for other artists. “It’s impossible to not see that own connection to my past. I’m reaching back and connecting with this kid I used to be.”

His eyes failing him, Hester relied on instinct and muscle memory to draw Shipwreck’s early panels in 2016. Fortunately, the comic’s stark setting played to his strengths of composition and storytelling, and Hester employed a pared-down, no-frills style that suited the Kafkaesque storyline and symbolism. On the opening page, Shipwright flails in the sea while a blackbird swoops overhead carrying a severed eyeball. Later, in an abandoned diner, the scientist encounters a crazed cook sautéing the eyes of a dead man.

Hester had noticed the first signs of vision trouble months earlier. It began with cloudy eyesight when he awoke in the morning, then lights began leaving glaring tracers. He assumed it was the side effects of his blood pressure medication, or maybe just part of approaching 50. But soon all bright light became unbearable. When he stepped outside, he felt like a coal miner emerging from a mountain.

“I COULD DEAL WITH THE MORTAL PERIL A LOT BETTER THAN I COULD DEAL WITH LOSING MY ABILITY TO DRAW.” Phil Hester contemplating a future without art

Known as a workhorse who typically cranks out a comic book a month—he’s published nearly 350 in his career—Hester began to miss deadlines and see assignments pile up. One book was canceled entirely when he failed to finish it on time. Finally, a trip to his optometrist and referral to UI Hospitals and Clinics unmasked the villain: Fuchs’ dystrophy, an inherited eye disease that attacks the inner lining of the cornea.

Fuchs’ dystrophy causes fluid to build up within the cornea, the transparent layer that covers the front of the eye, resulting in the tissue swelling and thickening. It’s a relatively common condition that affects about 4 percent of people over age 40, and while there’s no cure, it can be treated. Hester’s case, however, was rapidly advancing, and UI doctors drew up an aggressive strategy: a corneal transplant using donor tissue from the Iowa Lions Eye Bank, a nonprofit affiliated with the hospital and the UI Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

As it happened, one of Hester’s biggest fans would play a crucial role in his transplant process. Years ago, comic book collector Syed Hashmi (96BA) spent a day shadowing Hester in his studio to learn about the craft, and the two have been friends ever since. Today, Hashmi is a lab technician at the Iowa Lions Eye Bank, where he works as the lead tissue processor. Hashmi has prepared more than 5,000 corneas for transplant recipients in his seven years at the eye bank—including personally readying two new corneas for Hester’s procedure. Says Hashmi: “To be able to help my friend, it makes me feel good about what I do.”

Using tissue prepared by Hashmi and procured from an anonymous organ donor, UI clinical ophthalmology professor Kenneth Goins performed Hester’s first partial thickness corneal transplant in summer 2016. The hour-long outpatient procedure, which is conducted under anesthesia, required Goins to make a tiny incision on the edge of the cornea before stripping out the delicate inner lining and injecting the scrolled strip of donor tissue that’s one-hundredth of a millimeter thick. Goins then used special instruments to “unscroll” the transplanted layer, center it, and secure it in place with a gas bubble.

Hester was in good hands. UI Hospitals and Clinics and the Iowa Lions Eye Bank are known as international leaders in corneal tissue procurement, preparation, and research. Even more, Goins—medical director of the Iowa Lions Eye Bank—was the first surgeon in the state of Iowa to perform modern partial thickness cornea transplantation.

Goins’ colleague Mark Greiner, assistant professor in the UI Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, estimates that UI surgeons perform between 250 and 300 corneal transplants a year, and about 50,000 are conducted in the U.S. annually. “It’s a very safe procedure with a 98 or 99 percent success rate and less than a 1 percent chance of rejection,” says Greiner, who also serves as associate medical director at the Iowa Lions Eye Bank.

When Hester removed his eye dressing, the results were dramatic. He was told it would likely be a couple of weeks before he could return to work, but he hurried to his studio—in a single bound, if he could have—to start work on Shipwreck No. 2. Even with just one good eye, it was as if he’d transformed from Daredevil (the blind, cane-swinging hero) into Hawkeye (the sharpshooting archer from Iowa) overnight.

Once it was clear the initial procedure was a success, Goins performed the second transplant that fall. The results were “magical,” says Hester. His vision fully restored, he calls drawing the third issue of Shipwreck—and the many comics to follow—a three-person collaboration. “That includes my two donors,” Hester says.

More than a year later, Hester has become a passionate champion for organ and tissue donation and the Iowa Lions Eye Bank. Last spring he spoke at the organization’s annual memorial service at the Iowa Lions Donor Memorial and Healing Garden outside UI Hospitals and Clinics. He also shared his story at an Iowa Donor Network candlelight vigil this past fall, participated in the eye bank’s annual “giving tree” ceremony over the holidays, and illustrated a holiday card for donor families.

“He’s been such a great spokesman for us,” says Deb Schuett, constituent relations coordinator for the eye bank. “At the giving tree ceremony, he leaned over to me and said, ‘Anything you need.’ I think it’s a way for him to try to pay back not just what he’s been given, but just to let other people know about the impact it makes as someone who’s been through it—the near loss of vision, the surgery, then opening his eyes and seeing how everything has changed.”

Hester has yet to meet his donors’ families—it’s left up to those relatives if they would like to reach out to the transplant recipients—but he’s written a letter to each expressing his profound gratitude. While getting back to work was always his focus, he says becoming a member of the organ donor community has been the true reward. “I’d love to meet both of my donor families someday, but if that doesn’t happen, I’m OK with it,” says Hester, who had his sutures removed from his eyes in January after more than a year of healing. “Not to over-romanticize it, but you feel a general connection to humanity. I have pieces of two other people in me now.”

This month, the sixth and final volume of the Shipwreck series hits comic stands, concluding Jonathan Shipwright’s strange journey. It also serves as a milestone for its artist—a reminder of all he’s overcome since beginning the series. At age 51, Hester now enters what for many comic book makers is the prime of their career. With two healthy eyes and a renewed focus, Hester is currently drawing Batman Beyond and a new series based on Hanna-Barbera’s classic characters, among other projects. Even more, alongside his wife, Christine, Hester will soon be able to watch his children’s commencement ceremonies at the UI—son, Dean (16BS), is a geoscience graduate student and daughter, Emma, is a senior in psychology.

Hester is determined to honor his new collaborators by making the most of their gifts to him. After all, in his eyes, they’re the real superheroes of this story.