PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

UI nurses and nursing students hone their skills at ahigh-tech simulation lab.

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

UI nurses and nursing students hone their skills at ahigh-tech simulation lab.

Noelle screams in agony with each contraction. The 36-weeks pregnant woman has given birth before, and each delivery has been fraught with complications. This time, her blood pressure has spiked and she's at risk for seizures. The baby must be delivered immediately.

Nurses monitor Noelle's vital signs and administer magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures. Then they gather around to offer encouragement: "Take deep breaths...now push!" Two nurses stand by Noelle's legs as the nurse midwife guides the baby into the world.

After stabilizing the newborn, the midwife bundles infant Hal in a blanket and hands him to his mother. "Congratulations," she says. "It's a beautiful baby boy!" Then, she unzips Noelle and places the baby back in the womb, so the long-suffering pregnant woman can deliver again in a few hours.

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

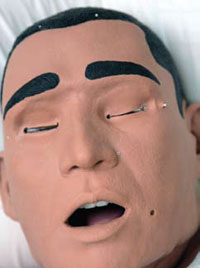

Hal's birth may sound like an episode of The Twilight Zone, but it's just another day in the life of UI students in the Master of Science in Nursing-Clinical Nurse Leader (MSN-CNL) program. It wasn't the typical delivery, because Noelle's not the typical patient. She's a full-size, lifelike mannequin designed to help UI College of Nursing students and UI Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) nurses practice delivery of quality patient care.

Equipped with blood, sweat, and tears, Noelle can simulate childbirth complications ranging from an umbilical cord wrapped around the baby's neck to postpartum hemorrhaging. A strong magnet and some lubricant push the newborn out of her body. "[Hal's birth] was such a moving event that some of the students were in tears," says UI clinical associate nursing professor Ellen Cram, 89MA, 02PhD. "They felt like someone was actually being born."

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

Noelle and more than 20 other realistic-looking mannequins are regular patients at the Nursing Clinical Education Center (NCEC), located on the fourth floor of General Hospital at UIHC. A partnership between the UI College of Nursing and the UIHC Department of Nursing Services and Patient Care, the 20,000 square-foot center gives students and practicing nurses a safe place to turn their knowledge into action before treating patients. Hospital staff members also use the area to refresh theirskills and keep up-to-date with rapidly changing technology.

Opened in 2006, the impressive facility features simulation labs for perioperative care, neonatal and pediatric intensive care, general pediatrics, adult medical surgical care, adult critical care, and pediatric and adult ambulatory care. Realistic replicas of hospital departments, the labs boast

cameras and microphones that can record simulated events onto a DVD for evaluation. The $6 million center also includes classrooms, offices, conference rooms, study space, a computer lab, and a resource library with a stunning view of Boyd Tower.

The UI was one of the first educational institutions to partner with a hospital on a nursing simulation lab, a benefit which has attracted both prospective students and registered nurses to Iowa City. Studies show that practicing with mannequins in a hospital-like environment improves patient outcomes and reduces errors in the real world. "We put [student nurses] in situations that are still within the scope of their practice, but at the edge of what they know," says Teri Boese, 78BSN, a UI associate clinical nursing professor and NCEC co-director.

Boese coordinates with UI College of Nursing instructors to prepare the fake patients for their parts. "It's like being a director of a play," she says. "[The professors and I] have different scenes with a script of what should happen and what we expect the students to do."

A costume and a few accessories go a long way in making the situations believable. Boese spends about an hour prepping the mannequins for each simulation. She fills internal reservoirs with dyed water, so patients can urinate, foam from the mouth, or have blood drawn from their veins.

iStan, one of the most advanced dummies, can be programmed to show the symptoms of more than 100 different diseases. He can present the vital signs of a normal healthy person, a 65-year-old smoking and drinking truck driver, or a buff young soldier.

If iStan plays a woman, Boese dresses him with a wig, makeup, eyelashes, and painted nails. She also stuffs a bra with the fake breasts that nursing students use to practice breast exams. Mannequin faces, arms, and other spare parts sit in a closet that rivals the eeriness of any Halloween store.

Boese goes to great lengths to give each simulation lab the feel, sound, and even smell of a real patient's room. When nursing students had to care for iStan after he suffered burns in a meth lab explosion, Boese dressed him in a shirt she'd deliberately burned in her home barbecue.

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

While they may initially feel silly talking to inanimate objects, nurses and nursing students quickly learn to take simulations seriously and treat mannequins with the respect due to a real patient.

Cram recently primed her MSN-CNL students for a juvenile diabetes scenario, discussing the normal blood pressure of a child (lower than an adult's) and whether it's a good idea to demonstrate drawing blood on a stuffed animal first (no, because children see stuffed animals as real). Then the nurses-in-training spent the next hour treating a dummy programmed as seven-year-old diabetes patient Joshua Smith.

Student Sara Newhart and her team walked into the general pediatrics room to find Smith lying in bed wearing an Iowa shirt and a John Deere cap. "Hi, my name is Sara, and I'm your nurse today," said Newhart, introducing herself to the boy and his mother (played by a professor), before explaining the steps she and her classmates were about to take.

The team immediately noticed that Smith was hooked up to monitors providing information about his heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature. "A nursing station is similar to the cockpit of an airplane," explains Cram. "There's a lot of data available—some is important and some is noise—and nurses need to know which is which."

Newhart recorded Smith's blood pressure and hung IV fluid, but she faced resistance when attempting to draw blood. "Mom, I'm scared!" cried Smith (Boese, hiding behind a screen with a microphone, gave a voice to the young mannequin).

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

Newhart calmed the boy down and then drew blood from his arm, before labeling the sample and sending it to the lab for testing. "I won't poke you anymore, okay?" assured Newhart, who soon realized she couldn't keep that promise. When lab results revealed high blood glucose levels, Newhart had to give the boy a shot of insulin. He shouted at her: "You're a liar! This place is full of liars!"

Later, Newhart and her classmates watched themselves on video and reflected on their performances. Pleased with the way they communicated with other team members, they realized they needed to work on interactions with patients. Newhart noticed that she talked loudly to Smith and hovered over him with her arms crossed. When she later cared for Noelle in the birth scenario, she remembered to address the patient at eye-level and to modulate her voice. "The simulations have taught me to be more self-aware when I walk onto the floor," says Newhart, "and that makes me a better nurse."

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

UI College of Nursing students spend six hours a week in the NCEC during their first semester and then use the facility throughout the rest of their education. By the time they graduate from Iowa, they will have given Noelle a bath, rehydrated a Hawkeye football player suffering from heat stroke, and defibrillated a middle-aged man with sudden cardiac arrest.

The spare body parts from the closet also come in handy: students use the arms to practice inserting IVs and the "Seymour Butts 900 Wound Care Model" to treat pressure ulcers common on the buttocks of patients restricted to beds or wheelchairs.

While previous generations of nursing students had to practice giving shots to real patients or to each other, the dummies offer a safer and more convenient alternative. Instructors no longer struggle to schedule hands-on learning opportunities that also fit into the hectic lives of UIHC patients and healthcare providers. The mannequins can just as effectively help future nurses bring the concepts in their textbooks to life. "We've moved away from having students sit passively in lectures to giving them an active role in showing us what they know," says Cram.

Mannequins also better prepare nurses for emergency situations where split-second decisions could have life-or-death consequences—although only in an end-of-life simulation does the patient actually die. "With the simulations, students learn to act on early cues and become astute on what they might expect from patients. Humans are unpredictable, though, so nurses always need to have a plan B," says Cram. "Anticipatory thinking is a tough skill to learn, but it's essential to patient safety."

Despite all their capabilities, simulated patients do have their limitations. Noelle and iStan may excel at imitating cardiac and respiratory diseases, but they lack the musculoskeletal movement that would help a nurse train to care for a Parkinson's patient or a stroke victim.

"The robots blink and move their eyes, but you can't do a full neurological exam on a patient who doesn't have the ability to respond," says Lou Ann Montgomery, 88MA, 00PhD, NCEC co-director and UIHC senior associate director, who oversees orientation, competency, and continuing education for the UIHC's 2,500 nurses.

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW ADPRO DESIGN

As the mannequins become more advanced, more simulations will likely take place in actual hospital environments. Healthcare workers can also look forward to more simulations that take advantage of interdisciplinary collaboration. Already, Newhart and her nursing classmates have practiced anesthesia with future physicians in the UI College of Medicine's simulation lab.

When they leave the classroom for the patient room, NCEC-trained nurses take with the practical experiences and skills that they may have never acquired without the help of Noelle or iStan. Newhart recently diagnosed a cancer patient with congestive heart failure after listening to her lung sounds—a condition she wouldn't have recognized without first hearing iStan's crackled breathing.

The experience gave Newhart greater confidence and also made her patient feel more at ease.

Who knew you could learn so much from a dummy?