Nestled high on a shelf at the UI Athletics Hall of Fame sits a team trophy, keeping company with almost two dozen wrestling awards and one for field hockey. The assembly of wood and metal honors the University of Iowa's national title-winning teams, the best Hawkeyes of all time.

This particular trophy has an unusual story to tell. A quiet symbol of the first time a UI team ever won a national championship in any sport, it's one of few nods to a little-known achievement in Iowa's athletic history. Few people have ever heard the story of forgotten champions who have only recently been truly celebrated.

The athletes who earned the trophy and accomplished this significant feat rarely felt the spotlight. They didn't run the gridiron, storm the court, or dominate the mat. Who are the UI's first-ever NCAA champions? Not the adored football or basketball players, not the storied wrestlers. They are the Iowa men's gymnasts.

Despite their enormous accomplishment, these men received no party or fanfare. Not only was the entire campus on spring break, but, as the gymnasts returned to Iowa City in 1969, a controversy regarding allegations of racial discrimination against the athletic department exploded.

"I don't think it hit us that we'd made history until [former Hawkeye sports reporter] Al Grady had an article in the paper a week or two afterwards," says Keith McCanless, 69BBA, two-time NCAA pommel horse champion and one of three seniors on the team that year. "We were excited, but it didn't really dawn on us, 'My God, what did we do?' Years later, I read Al's book and realized that our little meet was nothing compared to the civil rights movement. No wonder it got lost."

Forty years after their victory, team members finally received the recognition they've long dreamed about—and deserved.

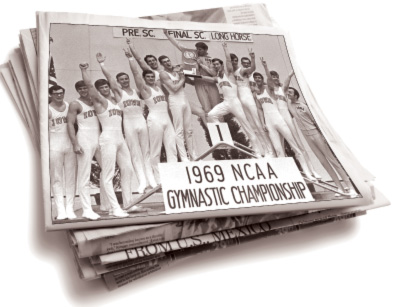

On April 5, 1969, at the University of Washington in Seattle, 14 members of the UI's men's gymnastics team took the winners' stand and proudly hoisted their trophy in victory. The joy in that photo is palpable. With unfaltering resolve, they had pulled away from rival Penn State to claim the title. At long last, after first entering intercollegiate competition in 1889, the University of Iowa finally had a national championship. It was a moment 80 years in the making.

Keith McCanless—the first Hawkeye gymnast to repeat as national champion—executes perfection on the pommel horse.

Keith McCanless—the first Hawkeye gymnast to repeat as national champion—executes perfection on the pommel horse. The tournament took place during the first weekend of the UI's spring break. A ghost-town emptiness descended on Iowa City as most students left for home or on vacation. Although the Daily Iowan published a trophy photo, papers fell on doorsteps of vacant homes. By the time the gymnasts came home the following week, their achievement was already yesterday's news, overshadowed by volatile civil rights issues that punctuated the late 1960s.

On April 16, two days after spring classes commenced, Iowa football coach Ray Nagel confirmed the dismissal of two black athletes, both starters, for what he characterized as personal problems. Two days after that, 16 of 20 black football players on the team boycotted practice. Nagel immediately declared them off the squad. The players claimed to have walked out in protest against an "intolerable situation" for all black people at the university. On April 20, a newly formed Black Athletes Union presented a racially charged open letter to the public with words that seared the football program to the bone:

"It has been stated that the university has an integrated football team and an integrated community. We maintain that this is not completely true. Brought into focus here is the slave-master relationship. The black athlete, for example, is the gladiator who performs in the arena for the pleasure of the white masses.... When Jesse Owens resisted the white pig-master following the 1936 Olympics, he was stripped of his athletic standing and allowed only to race horses. Psychologically emasculated, he represents no challenge. Today, the black athlete will not accept the same treatment."

The social, political, and media frenzy that ensued demanded the community's collective attention for the months that followed. Spring practice ended without a resolution to the walkout, but then-President Sandy Boyd and other UI administrators worked diligently for a resolution. By August, 12 of the boycotted players made appeals for reinstatement and seven were allowed to return to the squad.

During Iowa's first and only national championship season, the achievements of the men's gymnastics team had virtually faded into obscurity.

Four decades later, Keith McCanless found the films.

Last year, while cleaning the basement of his house, McCanless discovered in a dusty box film footage that his dad had shot from the Seattle grandstands at the NCAA meet. Misplaced and forgotten for years, the film puzzled McCanless at first because he couldn't even get his dad's old projector to work so he could view it. Around the same time, he received word of a second lost film, this one from ABC's Wide World of Sports. The ABC film covered the 1969 individual event championships and included highlights of McCanless's winning pommel horse routine, as well as performances by fellow gymnasts Don Hatch, 69BBA, and Bob Dickson, 70BS.

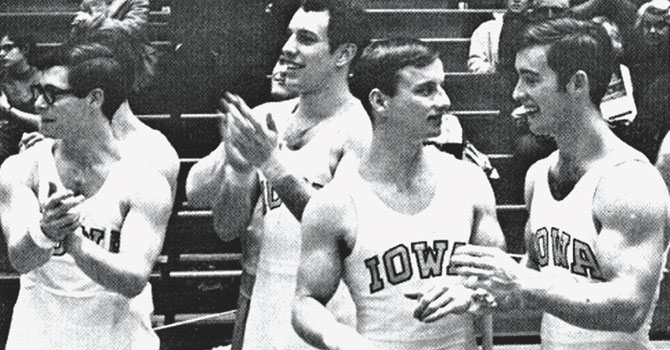

Bobby Dickson, Phil Farnam, Rich Scorza, Ken Liehr, and coach Mike Jacobson celebrate after another thrilling performance during NCAA team finals.

Bobby Dickson, Phil Farnam, Rich Scorza, Ken Liehr, and coach Mike Jacobson celebrate after another thrilling performance during NCAA team finals. Coincidentally, McCanless happened to be taking a community college course on digital photography and his final project was to make his own film. He took the best team footage from both these videos, spliced them together into DVD, and created a tribute to his teammates.

All the memories came flooding back. McCanless felt strongly that the time had come to revisit this incredible event in their lives. He wanted to share his movie with his friends and let them know their shining moment was not forgotten.

As he was finishing his film, McCanless noticed on the UI's website that a gymnastics team had recently held a ten-year reunion. He sent an e-mail to head coach Tom Dunn, asking him how the university might feel about inviting back its oldest national championship team for a 40-year reunion. Dunn thought that was a fantastic idea, and the men made their plans.

Coinciding with the 2009 football season-opener in early September, almost all members of the team and their coaches reunited in Iowa City for a celebration. They met first at the North Gym, where they spent so much time together, and then tearfully watched McCanless's movie at the Athletics Hall of Fame. They paused to gaze at their trophy and attended the Varsity Club Dinner—where UI President Sally Mason offered heartfelt words of congratulations and gratitude. The veteran gymnasts compared aching joints and arthritis pains, the wear and tear of a physically merciless sport. Just before the game against Northern Iowa, they took the field to thunderous applause made all the sweeter by the passing years. McCanless passed out copies of his DVD to everyone on the team.

"Our experiences of winning Iowa's first championship bonded us for life," McCanless says. "The team championship always meant more to me than any individual accomplishment. I think everyone had the same feeling, which is why our reunion was so well attended. Everyone wanted to get back to that day. The university did so much for our team. We were practically celebrities."

They all agreed that it was better late than never.

By the late 1960s, the Hawkeye men's gymnasts had earned a reputation as national contenders. They'd already made consecutive trips to the NCAA tournament the previous two years. Although considered the school to beat both of those years, the team fell short. Iowa placed third both times.

The gymnasts determined not to let that happen again. McCanless and the other seniors, in particular, were hungry to win.

Dick Taffe, Phil Farnam, Don Hatch, and Bobby Dickson react to the official announcement that Iowa was the NCAA winner.

Dick Taffe, Phil Farnam, Don Hatch, and Bobby Dickson react to the official announcement that Iowa was the NCAA winner.Competition proved fierce in 1969, though—it would not be an easy road back to the NCAAs. However, factors fell into place that secured a national berth, including a crucial rule change that eliminated trampoline (the University of Michigan's strongest event) from NCAA competition. Instead of seven events, the tournament would be decided based on the traditional six Olympic events (pommel horse, high bar, floor exercise, rings, vault, and parallel bars). The rule change allowed Iowa to edge out Michigan in the Big Ten NCAA qualifying meet and become one of eight U.S. schools to compete for the national title in Washington.

The NCAA preliminary round eliminated five schools. Only Penn State, Iowa, and Iowa State advanced to the team finals. Adrenaline pumping, the gymnasts marched out onto the floor. Iowa knew Penn State held a slight lead at the start of the final day. Interestingly, current UI head coach Dunn was a member of the Penn State team that year.

The Hawkeyes wouldn't accept defeat, however. Every single team member completed his routines with flawless grace. The team won its title by less than three-quarters of a point, securing the title on the parallel bars, the very last event in the six-event rotation.

"We hit all our events right out of the gate; we executed on all cylinders," says McCanless, who enjoyed a perfect ending to his athletic career.

Mike Jacobson, Iowa's rookie head coach in 1969, could hardly believe his luck. He'd inherited an elite group of athletes from previous coaches Dick Holzaepfel and Sam Bailie, 57BA, 60MA. Jacobson credits his assistant Neil Schmitt, 70BA, with much of the team's success—many athletes came to Iowa from Chicago because they'd gone to high school with Schmitt and followed him here.

Jacobson himself had been a gymnast at Penn State when the team won the national championship in 1965. Only a few years older than the young men he coached, Jacobson held a previous position with the Naval Academy in Annapolis, where he had served as an assistant coach.

"Our Iowa team had a spirit that I hadn't seen anywhere else," recalls Jacobson. "I don't think many people realized the obstacles we had to overcome. We had so many injuries that year, but we won every meet we needed to win to reach that NCAA competition. Going into that last day, there was so much pressure. It was incredible to win and one of the great highlights of my career."

Before his first year at the UI began in the fall of 1968, Jacobson remembers a moment when he first realized the magnitude of racial tension in the country. He was still with the naval academy and working for the Vice President's Summer Youth, Sports, and Recreation Program. He flew into Washington, DC, on a giant transport plane on April 4, 1968, the day Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. The city was in flames—a preview of the riots and unrest to come.

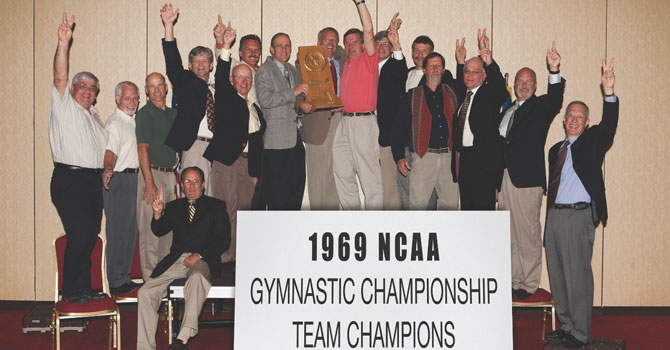

Together again for a 40-year reunion this past fall, the former UI gymnasts re-enact their historic moment on the winners' podium: (l-r) Donald Uffelman, Richard Taffe, Richard Sauer, Roger Neist, Donald Hatch, Barry Slotten, Richard Scorza, coach Michael Jacobson, assistant coach Neil Schmitt, Keith McCanless, Mark Lazar, Michael Proctor, Michael Zepeda, Jerome Bonney, James Morlan; seated, coach Sam Bailie. Not pictured: Robert Dickson, Phillip Farnam, Kenneth Liehr, Terry Siorek, coach Norman Holzaepfel.

Together again for a 40-year reunion this past fall, the former UI gymnasts re-enact their historic moment on the winners' podium: (l-r) Donald Uffelman, Richard Taffe, Richard Sauer, Roger Neist, Donald Hatch, Barry Slotten, Richard Scorza, coach Michael Jacobson, assistant coach Neil Schmitt, Keith McCanless, Mark Lazar, Michael Proctor, Michael Zepeda, Jerome Bonney, James Morlan; seated, coach Sam Bailie. Not pictured: Robert Dickson, Phillip Farnam, Kenneth Liehr, Terry Siorek, coach Norman Holzaepfel. He never thought any of this turmoil would reach the University of Iowa, but no campus went untouched. As Al Grady wrote in his book 25 Years with the Fighting Hawkeyes: "It is difficult, if not impossible, to look at the problems of that spring in Iowa City without looking also at what was happening throughout the United States, because what happened in Iowa City was not an isolated incident. In an historical sense, it was related to the civil rights movement and the black power struggle that had been fomenting across the nation throughout the 60s."

In a recent article for Slate magazine, former Notre Dame football player Michael Oriard traced the history of what he calls the "noisy [racial revolution that] took place on northern campuses."

Oregon State, the University of Wyoming, the University of Washington, and Indiana University all saw suspensions and boycotts as African-American players protested against perceived injustices and intolerance. Notes Oriard, "The racial revolution of 1969 changed college football."

Dick Taffe, one of just a few non-scholarship gymnasts on the UI's championship team, was a junior majoring in journalism in 1969. After the meet, he spent the rest of spring break home in Arlington, Virginia. Back on campus, Taffe jumped right into shooting anti-Vietnam War demonstrations—and the football controversy—as a photojournalist for the Daily Iowan.

"When we got back from the NCAAs, it was business as usual," Taffe says. "It was a kind of behind-closed-doors honor to be a gymnast. But I always knew we were the best. Our reunion was a touchstone to the whole state of confidence we had 40 years earlier."

Looking back, Sandy Boyd says he's long admired the team and has always been very proud of its accomplishments. "This was an extraordinary achievement," he says. "Unfortunately, some sports don't get the same attention as others, and I think this is a reminder to focus every year on sports that don't draw big audiences."

All the gymnasts agree that this past fall's reunion more than made up for any unintended oversight. Even though their parade was a long time coming, no one harbors any bitterness. Myriad factors complicated campus life that fateful spring. The fact remains that the UI's 1969 men's gymnastics team occupied a place in the history books all along. Never to be forgotten.