Sixty years ago, Don Gurnett spotted a new object in the night sky.

Only a few weeks into his first semester at the University of Iowa, the freshman electrical engineering student stood in awe at the foreign satellite passing many miles overhead.

The Soviet Union stunned Gurnett and the rest of the world on Oct. 4, 1957, by launching the first artificial satellite into orbit. Every 98 minutes, Sputnik 1 flew over the United States, its presence heightening the insecurities of a nation battling for dominance in the Cold War.

The stakes of the ideological showdown between the U.S. and Soviet Union were so high that many believed one misstep could lead to nuclear obliteration. Paranoia spread. Families and communities began building underground fallout shelters. Schoolchildren hid under desks after learning to "duck and cover" during monthly air raid drills.

PHOTO: Courtesy Time Magazine/Boris Artzybasheff

PHOTO: Courtesy Time Magazine/Boris Artzybasheff

"It was fearful," says Gurnett, 62BSEE, 63MS, 65PhD, who recently began his 52nd year as a distinguished UI physics and astronomy professor. "I can remember flying to Washington, D.C., many times during that Sputnik era, just hoping I wasn't there when the Soviets decided to hit Washington with an atomic bomb."

The launches of Sputnik 1 and 2, followed by the failed takeoff in December 1957 of the U.S.-built Vanguard TV3 (nicknamed "Kaputnik" after it exploded on the launch pad) devastated the American psyche. As Cold War fears escalated, America needed a hero.

Once again, Iowa native James Van Allen, 36MS, 39PhD, was the man for the job.

During World War II, the UI physicist helped develop and introduce the radio proximity fuse—a detonator that increased the accuracy of anti-aircraft missiles and led to victories in London, the South Pacific, and the Battle of the Bulge. Now U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower called upon Van Allen and other leading scientists to bring the nation to the forefront.

From his modest laboratory in the basement of the UI's MacLean Hall, Van Allen helped usher in an age of international space exploration and discovery that put Iowa students, faculty, staff, and alumni—including Gurnett—at the center of the country's efforts. The UI has since designed and built 62 scientific instruments for dozens of high-profile spacecraft missions that have visited nearly every planet and rapidly expanded human understanding of the solar system.

This fall, the UI Department of Physics and Astronomy celebrates the 60th anniversary of the start of the Space Race, the 40th anniversary of the Voyager missions that have flown into interstellar space, and the end of Cassini's 20-year mission orbiting Saturn and its moons. These cosmic achievements all began with the launch of Explorer 1—the first American satellite in space—on Jan. 31, 1958.

Discovery of the Age

Explorer 1 was America's answer to Sputnik. While Sputnik 1 didn't make any scientific observations, Van Allen and UI student George Ludwig, 56BA, 59MS, 60PhD, designed a Geiger tube that flew aboard the American satellite. The first scientific instrument in space—built at the UI—measured levels of cosmic radiation and sent data back to Earth for analysis in Iowa City.

On launch day, Van Allen joined top scientists and military officials in the War Room of the Pentagon, awaiting word of its success. "It was a really anxious period and silence settled over the whole group," Van Allen, who died in 2006, recalled for the biography, James Van Allen: The First Eight Billion Miles, by Abigail Foerstner. "We drank coffee and chewed our nails and wondered what had happened."

Finally, 108 minutes after liftoff, a receiver at the San Gabriel Valley Radio Club in California detected the satellite's transmissions. Tension melted into unbridled jubilation as the news reached the War Room. At 2 a.m., Van Allen joined other officials for an early-morning press conference at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. To his surprise, they were met with flashing bulbs and a mob of reporters. The scientists entertained questions and lifted a prototype of Explorer 1 over their heads in an iconic photo that made headlines around the world the next day.

However, the scientists' glee soon turned to concern as data suggested Van Allen's instrument wasn't working properly. Cosmic rays entering Van Allen's Geiger tube were supposed to ionize gas molecules, creating an electric rhythm for an onboard audio recorder to relay back to Earth. As the spacecraft signals were analyzed in the UI physics lab, a graphics plotter charted cosmic ray counts with robotic arms that glided across reams of paper. Students then measured the peaks and valleys for further numerical study by Van Allen and his team.

The researchers were puzzled to find prolonged gaps in data where the space sounds turned to static and graphs plummeted to zero. After further research with Explorer 3 in March 1958, Van Allen; fellow faculty member Ernest Ray, 51BA, 53MS, 56PhD; and students Ludwig and Carl McIlwain, 56MS, 60PhD, determined the areas of space with no cosmic ray readings were actually high-radiation regions rocketing off the charts. As Ray exclaimed in a note to Van Allen: "My God, space is radioactive!"

These regions—where the Earth's magnetic field collects charged particles—became known as the Van Allen radiation belts. With this breakthrough, Van Allen restored America's honor by making the first major discovery of the Space Age. This knowledge helped scientists assess the risks of human exploration and identify the safest orbits for astronauts. It also remapped the solar system and introduced new fields to space science in which the UI is a leader, including magnetosphere physics (the study of the magnetic fields of the planets and sun) and plasma physics (the study of solar wind).

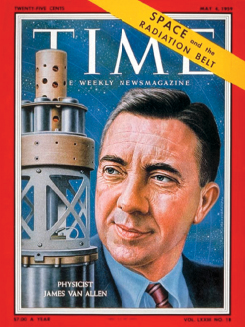

With his discovery, Van Allen became known as the "father of scientific space exploration," landing on the cover of Time magazine in May 1959. CBS News anchorman Walter Cronkite visited Iowa City to interview the new celebrity scientist, and the nation turned to Van Allen to hear his informed views on everything from sending astronauts to space (he was against it) to the safety of a microwave oven ("in my judgment," he said, "its [radiation] hazard is about the same as the likelihood of getting a skin tan from moonlight").

With Van Allen in the spotlight, the UI became a center for space research. Iowa's program grew exponentially as the U.S. took advantage of the UI's expertise to rival the Soviet Union. Led by Van Allen, a team of faculty, staff, and students did everything from design and build spacecraft and scientific instruments to run command centers and analyze data. From 1951 to 1975, the UI was home to the largest space instrumentation lab in the world, and the university helped send many satellites into orbit—including one called Hawkeye in 1974.

UI instruments currently active in space:

Voyager 1 and 2 - 1977

Mission: explore the outer planets, their moons, and interstellar space

Geotail - 1992

Mission: observe the Earth's magnetosphere

Wind - 1994

Mission: study radio waves and plasma in the solar wind and Earth's magnetosphere

Cassini - 1997

Mission: orbit Saturn to study the planet and its moons; mission ended Sept. 15

Clusters Salsa, Samba, Tango, and Rumba - 2000

Mission: study the Earth's magnetosphere through solar cycles

Mars Express - 2003

Mission: map Mars and study its atmosphere

Juno - 2011

Mission: determine Jupiter's origins and evolution

Van Allen Probes - 2012

Mission: examine Earth's Van Allen radiation belts

Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission - 2015

Mission: observe the phenomenon believed to cause aurora

The Next Generation

As a UI freshman, Gurnett couldn't have been more excited. Growing up in Fairfax, Iowa, he belonged to a model airplane club in Cedar Rapids, where he built radio-controlled planes and rockets alongside Collins Radio engineers. Now he had the opportunity to work under a world-renowned space pioneer.

Not long after watching the successful launch of Explorer 1, Gurnett boldly ventured into Van Allen's office to inquire about a job. Van Allen gladly put him to work, placing Gurnett among the first of more than 160 UI undergraduates over the years to receive hands-on experience in space instrument design, development, and building.

By 1960, Gurnett had become a project engineer on the Injun 2 and Injun 3 satellites while still an undergraduate—an incredible opportunity unheard of outside of the UI. "After the launch of Explorer 1, undergrads practically ran the place," he says of the college students who helped support the work of a burgeoning field. "Almost everybody was an undergrad."

With space research a top national priority, the UI physics and astronomy department moved quickly to keep pace with the Soviets, designing and building some scientific instruments and satellites in as little as six months. The physics lab stayed open 18 hours a day, seven days a week to accommodate the activity, with additional hours available for projects behind schedule.

During that era, Gurnett remembers walking home from work around dawn, hearing the robins sing and anticipating class later that morning. "There was tremendous pressure to catch up with the Russians," he says. "It was national, but focused here, because this was the beginning of the Space Race."

It also was the start of the UI's participation in some of NASA's greatest achievements. In 1972, Pioneer 10 became the first mission to fly beyond Mars to explore the radiation belts of Jupiter. Scientists weren't certain spacecraft could survive the asteroid belt and Jupiter's strong magnetic field, but Pioneer 10 exceeded all expectations. Van Allen contributed a Geiger tube telescope—the only instrument still working aboard the satellite when NASA lost contact with it in 2003, some 8 billion miles from Earth.

In 1977, Voyager 1 and 2 took advantage of a rare planetary alignment that allowed the probes to use a slingshot trajectory to travel farther and quicker. Building upon Pioneer's success, the twin spacecraft soared through the largely unexplored realm of the outer planets, giving the world its first close-up views of the ice and gas giants and their moons. Voyagers eventually became the farthest manmade objects from Earth at 12 billion miles.

Gurnett's onboard radio/plasma wave instrument, which provided insight into the magnetospheres of the outer planets, continues to produce data that now takes 19 hours to reach Earth at the speed of light. He'll never forget the moment when data from the instrument revealed that Voyager 1 had reached interstellar space in August 2012—an unprecedented achievement. "It was one of the greatest scientific events of my career," he says. "We were there at the beginning of discovery."

While these and other UI-affiliated projects have revealed much of what we know about the universe, the physics and astronomy department also has taken pride in advancing the educational mission of the university. Van Allen regularly invited students to participate in his research, treating them as equals and teaching them the joy of the scientific process. "I marvel to this day that I, as a largely untested student, was given so much freedom and responsibility for such an important endeavor," Ludwig, who died in 2013, once wrote. "My admiration for James Van Allen, with his willingness to take great risks with his students, is unbounded."

Indeed, many of Van Allen's students and their successors have become prominent figures in their own right, including Jim Green, 73BA, 76MS, 79PhD, NASA's Planetary Science Division director, and Stamatios "Tom" Krimigis, 63MS, 65PhD, emeritus head of the space department at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. At a 90th birthday party for Van Allen in 2004, many distinguished alumni returned to campus to pay tribute to their mentor. There, Ludwig—who later became NASA satellite systems' chief research scientist and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's director of operations—told a crowd of his peers: "Van Allen's lessons have stayed with me throughout my entire professional life. When attacking a problem, I frequently find myself musing, ‘Now, how would Van Allen do this?'"

The Legacy Continues

Van Allen's approach continues to guide the UI as it trains the next generation of space scientists, offering the same hands-on experience that Ludwig and Gurnett received 60 years ago. Today's students also benefit from the trusted partnerships that the UI first established under Van Allen, working in conjunction with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA, and the European Space Agency on some of the most exciting missions of our day.

Students flourish alongside mentors such as Gurnett, research scientist and engineer Bill Kurth, 73BA, 75MS, 79PhD, and senior engineering associate Don Kirchner, 78BA, who have many missions to their credit. Like Gurnett, third-year physics and astronomy major Zachary Luppen knocked on his professor's door as a freshman asking for work. Within his first month at the UI, Luppen had a key to Van Allen Hall and full access to the building's rooftop telescope. Now the Fort Dodge, Iowa, native proudly wears a Hawkeye lanyard carrying 13 keys to labs throughout the building.

Luppen is one of several UI faculty, staff, and students currently crafting an ice-penetrating radar that will search for life on the Jovian moons as part of the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer mission (JUICE). Based on the university's proven track record and experience creating a similar radar for Mars Express, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory invited the UI to join Italian scientists to build JUICE's principal instrument. Each day, Luppen and his teammates put on their protective suits and facemasks, ground themselves in the clean room, and fuse parts onto a circuit board that soon will orbit Jupiter. They also test models to ensure the instrument will survive some of the harshest conditions in the galaxy—including vibration, radiation, and extreme temperatures.

"At this university, I'm able to take part in some of the biggest things the human race is doing currently. I love what I do so much, I suffer withdrawal when I'm not working on the mission," says Luppen. "I've always wanted to be an astronaut, but this is the next closest thing where the pieces in my hands will fly up there in a rocket eventually. It's accomplishing a life goal, and it's so exciting."

Future UI-involved launches:

Fox-1D / (HERCI CubeSats) - 2017

Misson: give UI students experience in radiation mapping

HaloSat Cube Satellite - 2018

Mission: allow UI students to map the distribution of hot gases around the galaxy through X-ray detectors

Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer - 2022

Mission: study the presence of water and determine the habitability of Jupiter's moons

Europa Clipper - 2020s

Mission: orbit and study the Galilean moon