Love built the first UI Museum of Art.

An avid print and drawing collector, prominent Cedar Rapids attorney Owen Elliott, 1910LLB, had an appreciation for beauty. But nothing ever captivated him quite like Leone Lorimor, a colleague who shared his passion for the arts. During their courtship, Owen encouraged Leone to pursue a degree in art history at the University of Chicago, often joining her for weekend strolls through the Art Institute. On Leone's graduation day in 1929, the couple married and began traveling across India, Japan, and Europe to build an art collection—and a life together.

Throughout 53 years of marriage, the Elliotts visited art dealers, studios, and galleries around the world to acquire an extensive collection of 19th and 20th century paintings, prints, rare jade, and antique silver. They were among the last Americans to leave London before World War II and the first to return to Paris after the fighting was over, investing mere thousands on works by artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso that would later become multi-million dollar pieces. Then, in 1956, Owen suffered a severe stroke. Art suddenly turned into more than just the Elliotts' hobby; it became their hope for healing.

Ch'ing Dynasty, vase with lid, 1644-1911, jadeite, 6 1/2 x 3 x 1 3/4 in., University of Iowa Museum of Art, gift of Owen and Leone Elliott, 1969.187 A,B.

Ch'ing Dynasty, vase with lid, 1644-1911, jadeite, 6 1/2 x 3 x 1 3/4 in., University of Iowa Museum of Art, gift of Owen and Leone Elliott, 1969.187 A,B.

Doctors advised Owen—who lost his memory and ability to walk—to stay home and rest. Yet Leone used her husband's affection for the arts to restore his health. Beginning in 1958, she pushed Owen and his wheelchair around the museums and art studios of Europe. As they revisited their old haunts, Leone worked to rebuild Owen's memory. She shared with him the vivid details of their adventures, such as the time a flight attendant threatened to throw the precious Chinese jade they'd bought in Japan out of an airplane during a tropical storm. The jet needed to lighten his load, but Owen resisted: "If you throw that box out, I'll go with it," he said, according to Leone's 1980s interview with Iowa City broadcaster Dottie Ray, 44BA, 45MA.

Slowly, Owen's health began to improve, and the couple continued amassing art together. "[Leone] lived to be 103, and up until she was 102, she was able to describe their art collecting in the most wonderful terms," says longtime friend and Iowa City artist Shirley Brown Wyrick, 58BA, 76MA, 83MFA. "She could draw you word pictures that would transport you to an artist's studio where they were collecting."

While the Elliotts traveled the globe, the UI was busy making an impression as a leading university for the arts. By the early 1930s, faculty member Grant Wood had already achieved fame for his iconic American Gothic painting. Under the direction of modern art advocate Lester Longman in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s, the School of Art & Art History recruited other world-renowned faculty like Argentinian printmaker Mauricio Lasansky and painter Philip Guston. The school also purchased notable paintings such as Max Beckmann's Karneval and Joan Miró's A Drop of Dew Falling from the Wing of a Bird Awakens Rosalie Asleep in the Shade of a Cobweb, as well as nurtured a generation of creatives who flocked to Iowa to earn first-in-the-nation master of fine arts degrees. By 1951, the UI had established a reputation that led art collector and philanthropist Peggy Guggenheim to donate Jackson Pollock's famed Mural.

As the Elliotts began considering the long-term future of their collection in 1962, the UI's devotion to arts education drew their attention. They invited UI President Virgil Hancher, 18BA, 24JD, 64LLD, and School of Art & Art History Director Frank Seiberling to their home with a monumental challenge.

The Elliotts offered the UI their impressive art collection—at the time worth more than $1 million—with a small wrinkle: the university had to raise $1 million to build an art museum where these masterpieces could be appreciated, studied, and preserved under one roof. Loren Hickerson, 40BA, the director of the UI Alumni Association and newly fledged Foundation, mobilized the fundraising charge, calling their gift "one of the great blessings of university history" that would eventually lead to the arts campus we know today.

The Elliott Collection—along with other key paintings previously purchased by the art school—remain the core of what has become one of the country's most respected university art museums.

Building a Foundation

The Elliotts' gift would triple the size of the university's art holdings, which were at the time scattered across the Art Building and other places on campus. Hancher and Seiberling knew that an investment in the collection would only grow in value over the years, as well as raise the UI's profile in the fine arts. But the university had a problem—it had never run a major capital campaign before, nor did it have much organization in place to do it. Raising $1 million seemed daunting.

Regardless, Hickerson said the Elliotts put a "burr under the [UI's] saddle" by placing a July 1967 deadline on fundraising, after which they'd donate the art to rivals at the University of Nebraska with its already-established museum. Hickerson and his team agreed to move forward on the plan to raise the necessary funds—more than the sum total of all the private gifts in 115 years of university history.

Only seven years earlier, Hickerson and the UI Alumni Association had established the Old Gold Development Fund to foster alumni giving, leading to the 1957 birth of the UI Foundation. In 1964, Foundation leader Darrell Wyrick, 56BSChE, 57MS, was charged with guiding the museum campaign that would lay the groundwork for all future university capital efforts. With the Elliotts' deadline looming, he had no more than two years to accomplish the goal.

The grassroots effort began on campus, where faculty and staff showed their commitment to the project by donating more than $200,000 (twice their original goal). More than half came from the medical school, where cardiology professor and university campaign co-chair Lewis January persuaded faculty to donate $1,000 gifts. As an art enthusiast, January was concerned for the safety of Mural and other valuable pieces hung in haphazard places such as student painting studios and above the circulation desk of the Main Library.

Iowa City-area professionals and businesses matched faculty and staff giving with the leadership of banker W.W. "Bill" Summerwill, 32BA. Wyrick then joined incoming UI President Howard Bowen, 35PhD; UI Provost Sandy Boyd, 81LHD; newspaper publisher and campaign chairman Philip Adler, 26BA; new UI Foundation leader for annual giving Jerry Hilgenberg, 54BSPE; UI Alumni Association Director Joseph Meyer; and others on the road to rally support across the state and region. Everyone from schoolchildren to the heads of the Maytag Corporation chipped in what they could to build a great cultural resource for Iowa.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944), Kornacker (Grain Field), 1917, oil on canvas, 37 1/2 x 47 1/2 in., University of Iowa Museum of Art, gift of Owen and Leone Elliott, 1968.37.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944), Kornacker (Grain Field), 1917, oil on canvas, 37 1/2 x 47 1/2 in., University of Iowa Museum of Art, gift of Owen and Leone Elliott, 1968.37.

Early Days of the Museum

By October 1966, campaign leaders became confident they would reach their fundraising goal. That fall, Adler proudly turned the first sod for the UI Museum of Art's groundbreaking northeast of the Art Building. To celebrate, the art school hosted an exhibition of selected works from the Elliott Collection.

UIMA planners took advantage of a new Iowa State Board of Regents policy that allowed state architectural firms to work alongside nationally recognized design firms on university buildings. Designed by Harrison & Abramovitz—the firm responsible for the United Nations headquarters in New York—the museum established a legacy of partnership matched today by Art Building West, Hancher Auditorium, and the Visual Arts Building.

Bushoong; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Southern Savannah Mask, wood, feathers, 13 x 12 x 13 in., University of Iowa Museum of Art, The Stanley Collection X1990.650.

Bushoong; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Southern Savannah Mask, wood, feathers, 13 x 12 x 13 in., University of Iowa Museum of Art, The Stanley Collection X1990.650.

The UIMA opened in May 1969. Volunteers prepared wall labels for the art, polished the Elliotts' jade with a toothbrush, and baked cookies and cupcakes for the grand opening. The museum featured a central sculpture court with an oculus, permanent and temporary exhibition space, a conservation lab, and a 100-seat auditorium.

German abstract expressionist, collector, and professor Ulfert Wilke, 47MA, presided over the new institution as its first director. Far from an arts snob, Wilke was an animated mentor who made art accessible to the public and enjoyed close friendships with many contemporary artists highlighted in the UIMA galleries, such as Beckmann and Lyonel Feininger.

African Roots

One of Wilke's greatest legacies to the university was his influence in inspiring museum patrons C. Maxwell Stanley, 26BSE, 30MS, and his wife, Betty Holthues Stanley, 27BA, to expand their knowledge and collection of African art. The Muscatine couple's interest began in 1960 while visiting Liberia on a business trip for Stanley Consultants engineering firm, and under Wilke's encouragement, the Stanleys began subscribing to art magazines and catalogs, visiting reputable galleries, and drawing the attention of top art dealers. Over the years, they accumulated more than 800 ritual masks, religious figurines, and other pieces representing the finest African art in the United States.

The Stanleys' commitment to give the collection to the UIMA prompted the School of Art & Art History to strengthen its African arts studies program. With the Stanleys' support in 1978, UI School of Art and Art History Director Wallace Tomasini hired Christopher Roy as the Elizabeth M. Stanley Faculty Fellow of African Art History to become one of the first professors in the world to specialize in the field. In his almost 40-year UI career, Roy has used the Stanley Collection in all of his classes to expose hundreds of students each year to multiculturalism. "African art is so intimately tied to the lives of the people who made it," says the professor, who also created the Art & Life in Africa online educational resource. "The collection is not just about art; it's about the lives and history and cultures of all these people."

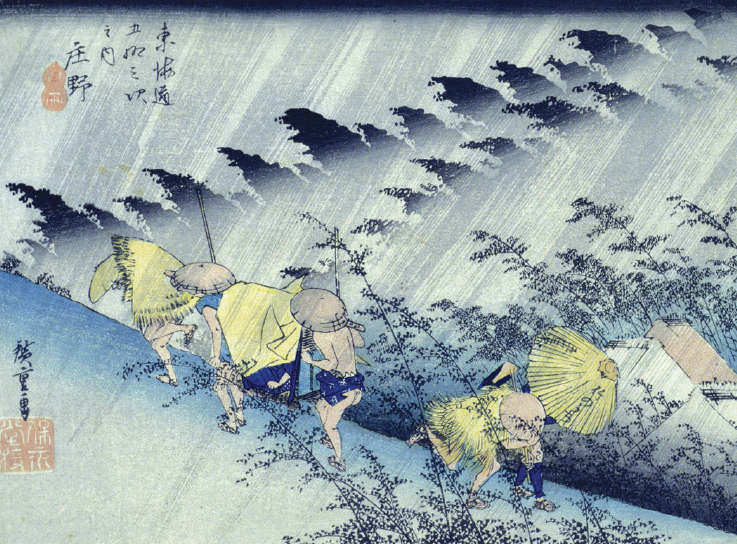

Ando Hiroshige (Japanese, 1797-1858), Shower at Shono, from Tokaido gojusantsugi nouchi (Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road), 1833, woodblock, 9 1/8 x 14 1/8 in., gift of Owen and Leone Elliott, 1974.8.

Ando Hiroshige (Japanese, 1797-1858), Shower at Shono, from Tokaido gojusantsugi nouchi (Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road), 1833, woodblock, 9 1/8 x 14 1/8 in., gift of Owen and Leone Elliott, 1974.8.

Creating an Arts Campus

While the Stanleys were building their African art collection, the Iowa Center for the Arts was established with the intention of enriching Iowa's reputation in areas such as art, music, and theatre. During this era, UI alumni and friends contributed to help build a printmaking wing for the Art Building (1968), the Voxman Music Building (1971), Clapp Recital Hall (1971), and Hancher Auditorium (1972).

The UIMA also expanded during this artistic renaissance. In 1971, Muscatine businessman and philanthropist Roy J. Carver gave money toward a 27,000 square-foot addition to the UIMA that opened five years later. Visits to the museum increased dramatically during this time as volunteers organized an educational outreach program that would bring Iowa schoolchildren to the UIMA for years to come.

Weathering the Storm

All of the museum's artwork remained dry in 1993 when flooding of the Iowa River closed the museum for most of the summer. Yet the UIMA faced an even bigger challenge in June 2008 when a 500-year flood threatened the UI's art campus. This time, it wouldn't be a near miss.

About a week before the flooding, the Army Corps of Engineers warned the museum to prepare for an evacuation. Volunteers and staff scrambled to save the collection, beginning with the pieces of greatest value: Pollock's Mural, Beckmann's Karneval, and Feininger's In a Village Near Paris (Street in Paris, Pink Sky). After building crates for the works, staff loaded the masterpieces onto refrigerated trucks bound for a storage unit in Chicago. University vans took archival boxes filled with drawings and prints to the Old Capitol for safekeeping, while ceramics, jade, and sculptures were moved to higher ground within the museum.

On a notably unlucky Friday the 13th, floodwaters closed off all access to the museum. Though the UIMA didn't lose any works of great importance in the disaster, it did lose its home of nearly 40 years.

Turning Tragedy into Opportunity

In these years without a building, the UIMA has become more determined than ever to share Iowa's artistic legacy with the university community, state, and world. Passionate about the UI's role in the development of modern art in America, Sean O'Harrow—who directed the UIMA through the challenging post-flood years before leaving for a new career opportunity in Hawaii earlier this year—used his tenure to bring Pollock's Mural and other cherished pieces before more eyes than ever before. UI law faculty member James Leach, a former U.S. House of Representatives member and chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, now serves as interim UIMA director while the search for a new head is underway.

Iowans can still see select works from the UIMA at the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa, and in the Iowa Memorial Union's former Richey Ballroom and Black Box Theater. Yet the collection has also become a source of pride in towns as far away as Sioux City through UIAA-hosted alumni events and the UIMA's new "Legacies for Iowa" statewide art-sharing program supported by the Matthew Bucksbaum [49BA] family. Other museum educational programs this past year brought art education to senior living communities and to more than 65,000 K-12 students statewide. In the 2015-16 academic year, UIMA events and exhibits attracted an unprecedented 627,672 visitors.

The Future of the UIMA

Still, the UIMA is eager to lift its collection from storage, providing more educational opportunities for students and the general public at a time when the arts are at stake.

"So many people think the museum is a luxury, not a necessity, but in fact it's at the heart of what we do in the arts and central to a university education," says UI art history professor Joni Kinsey. "There's no substitute for standing in front of and learning from an original work of art."

After first pursuing a plan to build the new museum on private property downtown for more than $80 million, the UI has cut costs down to roughly $50 million and improved student and academic connections by finding an on-campus location. In June 2016, the Board of Regents approved the UI plan to locate the new art museum just south of the Main Library on Burlington Street. A combination of university funds and private gifts will pay for its completion.

Located at a central campus hub of activity, the museum will leverage stronger collaborations with the College of Education and the UI Libraries and provide more space for students to be exposed to and immersed in the world of fine arts. Design is well underway, and UI President Bruce Harreld has pledged to complete construction near the end of 2019 to mark the 50th anniversary of the UIMA.

With a long-awaited building finally on the horizon, staff look forward to carrying on the vision of its founding contributors, Owen and Leone Elliott, who believed in keeping art at the heart of the university's educational mission.

Mural's World Tour

Jackson Pollock's Mural is widely considered the most important painting of the American modern art movement. Former museum director Sean O'Harrow's work to uplift Iowa's cultural standing during the post-flood years began by preserving this focal point of the UIMA's collection. In July 2012, Mural arrived at the Getty Conservation Institute in California for an extensive two-year study and conservation process. Current UIMA advisory board member Joyce Summerwill, who used to visit the museum every Friday to find solace in the Pollock, saw the painting again at the Getty shortly after its cleaning. Describing the visit as akin to a religious experience, she says, "I cried, because I'd never seen such beauty."

Over the past eight years, Mural has attracted record-breaking crowds to venues in dozens of cities around the world—from Los Angeles and Venice to Berlin and London—inspiring three books and a film. "What else in the world has had that kind of attention?" says UIMA senior curator Kathleen Edwards. "I could count on one hand the art in history that could generate this kind of international [buzz]."

To watch an Iowa Public Television documentary on the painting's incredible journey, visit http://bit.ly/IPTVpollock.