PHOTO: JOSH O'LEARY

PHOTO: JOSH O'LEARY

M

elissa Fath knows this chair all too well. Extra roomy. Cushiony but not too cushiony. A view of Kinnick Stadium out the window. A visitor's seat for her husband or book club friend to keep her company. A pillow to rest her arm while the drugs trickle into her vein.

She reclines and a nurse brings her an iced tea. Seventeen times this past year she's spent the day in this chair, or one of the 39 others just like it, nearly all of which are occupied at the moment by patients tethered to IVs. She waits as the antibody, a targeted cancer therapy drug called Perjeta, eases its way into her bloodstream. The drip drip dripping of the IV bag marks the minutes, then hours, over her shoulder.

Looking around the UI Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center's infusion center, Fath recalls the grand opening ceremony of the gleaming new $12-million clinic, which now seems a lifetime ago. Fath, 90BSPh, 01PHD, a UI assistant research scientist studying neuroendocrine tumors, was among the researchers present for the 2012 ribbon-cutting to showcase their work. But that was before she knew one of those chairs was intended for her. Before she went from cancer researcher to cancer patient.

Three years later, she stood in the shower, circling her fingers around the small lump.

Fath has spent the last decade evaluating the characteristics and behavior of tumors under her microscope, so she knows this enemy well. Yet, the breast cancer diagnosis still frightened her. While researchers like Fath gain ground by the day—with new targeted therapies, immunotherapy, and high-dose Vitamin C treatments showing particular promise—it's the unpredictable and often arbitrary nature of the disease that leaves a patient vulnerable. The cruelness of cancer was underscored further for Fath and her colleagues earlier this year with the failing health of UI surgical oncologist James Mezhir, whom she had worked with in his laboratory. Like Fath, Mezhir found himself in the patient' chair, the decline of this brilliant young doctor yet another casualty on the long and painful road to better treatments.

"The thing that makes cancer worse than other diseases and why people are so afraid of it is it can be completely random," says Fath, a 50-year-old mother of three. "It strikes healthy people."

The young, the old, the ailing, the strong—cancer is indiscriminate when choosing its victims.

An IV bag empties, then it's on to another. Fath points out the bright pink scarf she's wearing to mark the occasion. Although identical in process 17 times over, this treatment is different. This is the last one.

Progress, but growing complexity

According to the American Cancer Society, death rates in the U.S. have fallen over the past two decades in the four most common cancer types: lung, colorectal, breast and prostate. Still, cancer accounts for one out of every four deaths in the U.S., second only to heart disease. An estimated 1.7 million new cancer cases will be diagnosed this year in the U.S., and 595,690 Americans likely will die.

For patients like Fath, whose breast cancer was discovered at an early stage, the good news is survival rates continue to rise and cancer is more treatable today than ever before. Leaders at Holden, one of 45 comprehensive centers designated by the National Cancer Institute, say precision medicine and personalized care continue to push cancer treatment and prevention into promising new territory. In his State of the Union Address in January, President Barack Obama made such work a national priority, calling for "a moonshot" to cure cancer—a $1 billion national research effort in the spirit of the Space Race last century. Vice President Joe Biden, whose 46-year-old son, Beau, died of brain cancer last year, will lead the initiative. But even as progress is made, the deep complexities of cancer continue to reveal themselves.

Holden Director George Weiner, also president of the Association of American Cancer Institutes, says as researchers burrow deeper into cancer's underlying causes, they're learning the disease is much more complicated than ever imagined. Says Weiner: "We now know that cancers that look identical under the microscope, and seem to be in very similar patients, can have very different causes at the molecular level."

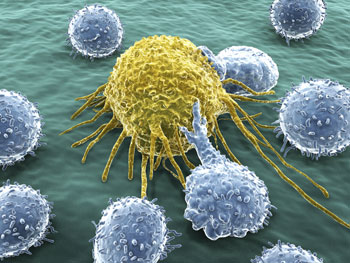

Cancer develops when cells begin to grow out of control and multiply, thereby crowding out healthy cells and often forming tumors. At cancer's roots lie hundreds of genes, if not more, that can mutate and drive those cells to behave abnormally. With scientists increasingly able to pinpoint these problem genes, new drugs continue to emerge that are designed to target and block the specific molecules causing a cancer's progression. That's opposed to traditional chemotherapy drugs, which kill healthy cells as well as the cancerous ones, leading to multiple side effects such as hair loss and severe nausea.

"The thing that makes cancer worse than other diseases and why people are so afraid of it is it can be completely random."

Melissa Fath

In Fath's case, her doctor used chemotherapy in conjunction with two targeted antibodies—Herceptin and Perjeta—to attack the gene behind her cancer's progression: HER-2. The antibody therapy proved much easier on her body than the chemo, with mild skin irritation the only apparent side effect. The National Cancer Institute warns that targeted therapies can create their own issues, however, ranging from diarrhea to liver problems.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved targeted therapies for melanoma, lung cancer, and prostate cancer, among others, with many more in testing and clinical trials as researchers uncover new genetic abnormalities. Researchers are on the cusp of this era, Weiner says, and doctors now understand that "one size fits all" does not work when it comes to cancer care.

"Cancer is not one disease; it's hundreds if not thousands of diseases that are different in individual people," adds Michael Henry, UI associate professor of molecular physiology, biophysics, and pathology. "We don't have a way of tackling cancer across the board; we're making advances in one area at a time. We all share the goal of curing cancer, but what that means is there is not one pill in a bottle that will prevent or cure all cancers. It's a lot of little things that we're making good progress on lately."

A life devoted

Before he was a rising star in oncology at the University of Iowa—and long before disease would again lay siege to his body—James Mezhir was 15 when he first learned the devastation of cancer in 1988. He was a runner on his high school's track team in Grand Island, N.Y., when he began waking at night with a crushing pain in his chest. At first, he dismissed it as being sore from lifting weights. After a few weeks, the pain worsened to the point that he was rushed to a nearby children's hospital where he began vomiting blood.

A scan revealed the tumors in his chest and stomach. The young Mezhir had non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, a diagnosis that led to 17 hours of surgery and a year of chemotherapy treatments. Thanks in part to his athleticism and general good health, Mezhir emerged cancer free and inspired to pursue a career in medicine.

While in school at the University of Buffalo, Mezhir wrote about what it was like to find his calling: "Having the opportunity to be a medical student after being a cancer patient is one of the most incredible life experiences imaginable. Among other things, it seems to finally lend meaning to what happened to me as a teenager. It also helps me realize that there's a big difference between reading in a journal about survival rates and having to face the statistic yourself."

After graduating with his medical degree in 2001 and working at the University of Chicago Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, Mezhir came to the UI in 2010, where his novel research and compassion set him apart. As a teenager, Mezhir had undergone a surgery called a Whipple procedure, which includes the removal of a portion of the pancreas. As a doctor, he worked to help those with pancreatic cancer—one of the most difficult cancers to detect and treat.

"His passion was his patients, and he was able to connect on a personal level. He really knew what it was like."

Brianne O'Leary

In the clinic, Mezhir specialized in the treatment of pancreatic and other gastrointestinal cancers; while in the research lab, he made advances in free radical biology that could potentially prevent pancreatic cancer metastasis and translate to new therapies.

"His passion was his patients, and he was able to connect on a personal level. He really knew what it was like," says Brianne O'Leary, a research specialist in the James Mezhir Surgical Oncology Laboratory. O'Leary met many of his former patients and their families, who continued to support Mezhir's research long after their own cancer battles. "His patients really adored him. I know many of them had his personal cell phone number and he stayed in close contact with them."

Two new treatment pillars

At Holden and cancer centers nationally, targeted therapies like Fath's Perjeta and immunotherapy are among the new treatment areas yielding positive results. While traditional methods—surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy—remain important tools, Weiner says these approaches have become "two more pillars" in research and therapy.

The National Cancer Institute describes targeted therapies as the cornerstone of precision medicine, which uses information about a patient's genes and proteins to diagnose and treat disease, or prevent it entirely. Immunotherapy, meanwhile, harnesses the power of the body's own immune system to fight off cancer. Weiner says researchers have discovered how cancers shield themselves from the immune system and hope to find ways to expose those cells and trigger the body's natural defense system against them.

"The analogy I use is Harry Potter's invisibility cloak; the cancers have figured out how to hide from the immune system," Weiner says. "We want to get rid of that ability to hide. For many years, experts felt it never would work. Now it's working."

Over the past year, Mezhir's team has researched the possibility of using Vitamin C to treat gastric cancer. Among the biggest stories in cancer research at UI in recent years is the advancement of a decades-old idea that high doses of vitamin C (ascorbate) can increase cancer cells' vulnerability to traditional treatments. By delivering Vitamin C intravenously—in concentrations hundreds of times greater than when taken orally—it increases the stress level of cancer cells by boosting a toxin in them called reactive oxygen species. Then, when patients receive radiation or chemotherapy, the one-two punch is meant to push cancer cells off the cliff.

"This isn't something a drug company has gone after, because there's no patent on Vitamin C," says Henry, also deputy director for research at Holden, which is a front-runner on this frontier. "This is one area where academic research can really have an impact—taking things into the clinic that companies wouldn't take because the profit motive is not there."

A random mutation

Across the hall from the Mezhir lab, Melissa Fath has pinned a handful of cards above her desk inside UI's Medical Education Research Building. They're from people close to her whose lives have been scarred by cancer—words of encouragement to keep pressing forward. Even before she was diagnosed with breast cancer, those same friends and family provided her with plenty of motivation. Postdiagnosis, her work became more personal than ever.

Fath found being diagnosed with the subject of her expertise a mixed blessing.

Having worked as a pharmacist before moving into research, Fath once took painstaking measures when handling chemotherapy medications: gowns, gloves, masks, and special hoods were required to keep the chemo away from her skin and lungs. The thought of those drugs being directly infused into her body hit a visceral chord—so much so that she requested antianxiety medication before her first treatment.

At the same time, Fath knew the odds of beating breast cancer were good. She was well-versed with the survival graphs—those with stage I breast cancer have a 100 percent five-year survival rate, those with stage II have a 93-percent chance—and she understood the effectiveness of new and traditional treatments. It was never a question of, "Why me?" Instead, she makes sense of her diagnosis in scientific terms: "A random mutation."

Fath's treatment began in spring 2015 with a chemo plan called neoadjuvant therapy to shrink her tumor prior to surgery. When it came time for her lumpectomy last summer, the mass had been reduced to a tiny point of live tissue.

An inspiring legacy

Melissa Fath and James Mezhir's paths crossed 25 years after he beat non-Hodgkin's lymphoma as a teenager. A year before Fath learned of her unexpected journey, Mezhir discovered his personal fight with cancer wasn't over. The married father of two was diagnosed with advanced gastric cancer, and this rematch would drag on nearly two years.

Mezhir's name was a constant fixture on his church's prayer list this past year. His colleagues say that despite his decline in recent months, he pressed onward in his work, continuing to study the very same cancer that had taken hold of him.

Holden researcher Douglas Spitz, 84PhD, director of UI's free radical radiation biology program, mentored Mezhir and collaborated on major papers investigating colon and pancreatic cancer. Spitz came to know Mezhir as a man driven by his family, his patients, and his science.

"We've all had family members who have died of cancer, but James experienced it personally," Spitz says. "It was really a bigger part of his life than I'm sure he wanted it to be. It was very inspirational to watch him work diligently, trying to stay positive and developing new therapies even as he had to go to surgery and do chemotherapy himself."

Mezhir's second fight with cancer ended on Feb. 3, when he died at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics at age 42. The week before his death, he was still in the lab—emblematic of his dedication to his life's work.

"He'll be greatly missed," says Spitz. "The more people like James that we have working together here at Iowa, the more progress we can make."

A milestone reached

Thanks to the commitment of scientists like Mezhir, more and more patients have hopeful endings. A month after his funeral, Fath waits patiently for her graduation from Holden. Her husband, Rod Sullivan, 88BA, joins her for this final infusion session.

There will be no grand pronouncement of being cancer free, no big balloon drop, no clean bill of health handed to her. Instead, she'll head back for a checkup in six months, then her annual exams. And she'll do her best to shove the 15 to 20 percent chance the cancer could return to the back of her mind.

"You go from actively fighting cancer through all of this, then all of a sudden you have to sit and wait and see what happens," she says. "So you're entering a much more passive time, sitting around waiting to get cancer again rather than actively preventing it with these infusions."

She will, however, have plenty to keep her occupied. Fath and Sullivan had canceled a trip to Italy last summer that they've begun to plan again. And Fath is at last ready to celebrate her 50th birthday, which came and went during treatment. A celebration of life party is planned for June, when Sullivan also turns 50, and the kegs, catering and karaoke are already in the works. They also keep busy with a 15-year-old foster daughter they recently welcomed into their home. Life moves forward.

The last of the antibody drips from the bag, down the plastic tube and into her vein, one last dose of medicine in search of those HER-2 gene receptors.

Melissa Fath adjusts her pink scarf and gets up from the chair.

Still fighting with Flash

PHOTO: SCHROEDER FAMILY

PHOTO: SCHROEDER FAMILY

He was five years too soon.

That's what doctors told Craig and Stacy Schroeder, whose 15-year old son, Austin, died a year ago this month at University of Iowa Children's Hospital. Had his cancer—a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma—developed half a decade later, new therapies might have been available.

Today, the Schroeders have become outspoken champions for cancer research to help make those treatments a reality.

The Fight with Flash Foundation donated $22,000 last year—22 was the number Austin wore on the baseball field, where he earned the nickname "Flash"—toward establishing a new adolescent and young adult cancer program at UIHC. The program is aimed at enhancing the medical and psychosocial needs of teenagers and young adults.

Flash first noticed a lump in his groin while on spring break with his family in Mexico in 2014. He was diagnosed with Stage III T-cell lymhoblastic lymphoma and would spend more than 100 days in the hospital over the next year, though little could be done to slow the disease's course. Austin died April 28, 2015, which, fittingly enough, was National Superhero Day.

While Flash's treatment was largely traditional methods, including chemotherapy, a bone marrow transplant, and radiation, the Schroeders are hopeful genetics-based targeted therapies could one day provide children with a better chance of beating cancer.

A year after Austin's death, the emails, Facebook messages, and text messages still pour in. Nearly every day, Craig and Stacy receive a note from someone who has been touched by Flash's story, often sharing how they've carried his mantra: "Win the day."

"People have taken that to heart, and we couldn't be more proud people are trying to live their lives that way," Stacy says. "It lifts us up and helps us keep moving forward."

The latest at Holden

Physicians and scientists in UI's Holden Comprehensive Care Center continue to forge ahead in the fight against cancer. Here are some notable advances made in recent months:

Tiny chip: UI engineer Fatima Toor, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, has formed a startup company called Advanced Silicon Group to bring to market a solar chip—smaller than a fingernail—that could quickly and inexpensively determine if a person has a specific type of cancer. The device would be covered with millions of nanowires, as well as the antibodies for specific cancer types. Using a high-powered laser, lab workers could view how a drop of a patient's blood reacts with the antibodies on the nanowire array. The hope is the chip will one day eliminate painful biopsies and detect cancer in its early stages.

Click here for the full Iowa Now article.

Vaccine awareness: A vaccine exists that could prevent tens of thousands of cancer diagnoses a year, but less than half of children in the U.S. are receiving it. Holden director George Weiner, along with the leaders of 68 other top cancer centers nationally, issued a statement earlier this year calling for the increased vaccination of human papillomavirus, or HPV, to prevent some of the 27,000 annual cancer diagnoses attributed to HPV infections.

Click here for the full article.

New grant: Cancer research at UI received a major injection of funding this past fall when the National Cancer Institute awarded Holden researchers $10.7 million over five years to study neuroendocrine tumors. The funding will allow UI researchers to investigate the genetics of these tumors, their molecular makeup and develop new approaches to diagnosis and treatment.

Click here for the full Iowa Now article.

Surgery study: A UI study that analyzed data from more than 21,000 women with stage IV breast cancer found that having a tumor surgically removed may improve outcomes. Stage IV breast cancer is generally considered incurable, and the overall medical view has been that removing the primary tumor will not benefit the patient once the disease has spread throughout the body. But the UI study, led by Alexandra Thomas and Mary Schroeder, showed an association between receiving surgery and prolonged survival in some women with advanced breast cancer.

Click here for the full Iowa Now article.