ORIGINAL PHOTO BY ROBERT D. RAY. COLLECTION OF THE STATE HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF IOWA

Influenced by his encounter with this young man and others seeking hope at Thai refugee camps during the mid-1970s, former Iowa Governor Robert D. Ray welcomed thousands of refugees from the Vietnam War to make their home in the Hawkeye State.

ORIGINAL PHOTO BY ROBERT D. RAY. COLLECTION OF THE STATE HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF IOWA

Influenced by his encounter with this young man and others seeking hope at Thai refugee camps during the mid-1970s, former Iowa Governor Robert D. Ray welcomed thousands of refugees from the Vietnam War to make their home in the Hawkeye State.

B

oots caked in mud, Robert D. Ray stood outside a thatched-roof hut at a Thailand refugee camp more than 35 years ago. The Iowa governor's guides had just taken him through a desolate field, where thousands of malnourished refugees lay on the threshold of death. Amidst all the suffering, they wanted to show Ray a picture of their "promised land."

Ray, 12LLD, entered the rickety building and discovered an official Iowa Department of Transportation map taped to the wall. Red and blue pins represented Iowa communities where the refugees' relatives had been welcomed into hearts and homes. Touched by stories of such Midwestern generosity, the refugees asked Ray if they could become Iowans, too.

Even prior to this diplomatic trip in October 1979, Ray had already offered Iowa as a symbol of hope to far-flung people in distress. Just a few years earlier, he became the world's first government official to accept several hundred of the millions of Cambodians, Vietnamese, Lao, Hmong, and Tai Dam who fled oppressive Communist regimes during the Vietnam War and other Southeast Asian conflicts.

Ray established Iowa's humanitarian legacy during the Vietnam Era, and Iowa has since served as a beacon of opportunity for generations of refugees from countries around the world. They've arrived in waves throughout history and time–for different reasons and under various circumstances–yet all finding Iowa a peaceful, quiet oasis from persecution and violence. They've made their homes in places like the Amana Colonies, Pella, and Des Moines, where they've contributed to their communities and to the state's patchwork fabric. Many like Louis Swaka have become valuable members of the University of Iowa community, with its promise of education, legal counsel, and support to those who forge a new life in Iowa City. A little more than a decade ago, Swaka was one of hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese refugees scattered across the world, and he pictured America "almost like the Garden of Eden, where everything was milk and honey."

Grateful for the chance to pursue a career as a biochemist instead of as a soldier, Swaka, 15BA, is now a UI medical laboratory scientist who persevered through school despite news that his cousin fell victim to the violence at home and from friends who thought they'd escaped civil war by fleeing to Syria and other nearby countries, only to encounter new political unrest. Says Swaka: "You don't have the luxury to decide where to go, so you take whatever exit window you can find. [My experience has] taught me that you should treat people well regardless of where you're from, because one day you might find yourself in the same shoes."

Now, Iowa and the world must decide how to respond to a new wave of refugees, as ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and Africa have contributed to the global displacement of more than 60 million people–the highest number since World War II. The outbreak of civil war in countries such as Syria has led to instability in the region, including the brutal treatment of citizens and the rise of terrorist organizations such as ISIS.

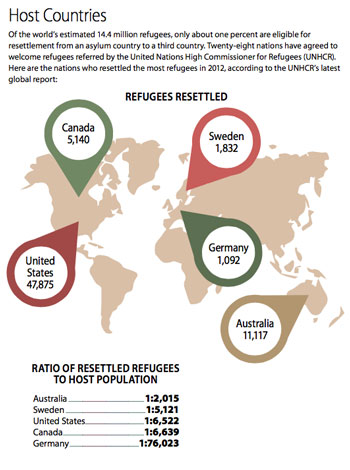

SOURCE: GLOBAL RESETTLEMENT STATISTICAL REPORT 2013, UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES

SOURCE: GLOBAL RESETTLEMENT STATISTICAL REPORT 2013, UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES

To flee their desperate situation, migrants and refugees have built makeshift rafts in hopes of crossing the Mediterranean Sea and Europe's borders for relief. Perhaps no other image showed the Syrian plight more harrowing than the picture of a little boy in a red sweater washed ashore on a Turkish coast. Alan Kurdi's family tried to sail from Turkey to Greece, but the toddler drowned in the perilous waters, instantly becoming an international symbol for the refugee crisis. Despite such tragedies, the chaotic and dangerous nature of this part of the world has ratcheted global concern about safety and security. Recent terrorist attacks in Paris and San Bernardino fuel fears and have sparked national debate among presidential candidates and current state governors about who should enter borders and how–and whether America can afford to open its doors to Syrians.

As Diane Tran, 04BSE, 08F, 08MD, watches the latest refugees stream out of Syria and other war-torn countries, she is reminded of her parents' journey to America more than three decades ago–and the realities of what it means to leave the familiar for a strange new land. Tran's parents are part of the Tai Dam ethnic minority group, also known as "the people without a country." Their families left Vietnam for Laos in the 1950s during the Vietnam-French War and then escaped to Thailand in the 1970s during the Laotian Civil War. Diane Tran's father, Ngoc Phu Tran, remembers coming home from school one day to learn that he and his family would leave Laos that evening. A taxi arrived to pick up the family in the middle of the night, so the Pathet Lao Communists wouldn't notice the departure.

Taking only a few photos and clothes in a backpack, Ngoc Phu Tran then spent 14 months in an overcrowded Thai refugee camp. He remembers standing in line for limited food and contaminated water. No jobs were available and many became ill as they awaited a new home. The Tai Dam people knew that scattering across the globe could mean the end of their language, heritage, and culture. They vowed to stay together as a group, sending a letter to 30 U.S. governors in summer 1975 to plead their cause. Only Ray responded. In July 1975, he established the Governor's Task Force for Indochinese Resettlement, the first- of-its-kind state program that allowed for the Tran family and nearly 90 percent of Tai Dam refugees to come to Iowa.

At a 2013 UI Provosts' Global Forum on "Refugees in the Heartland," World Food Prize Foundation President Kenneth Quinn praised Ray for laying the foundation for Iowa's moral leadership in refugee resettlement. "This was a momentous decision that changed the lives of these people and helped them preserve their culture," Quinn told Drake Blue, the magazine of Ray's alma mater, pointing out his work with Ray as a member of the U.S. State Department and as a former ambassador to Cambodia. "The legacy of his leadership is that Iowa has an amazing humanitarian [reputation for] easing human suffering." At the time, the State Department wouldn't allow large groups of refugees to settle in a single location, so Ray worked with President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to make an exception. The first 300 Tai Dam arrived in Iowa in October 1975. Nine months later, the Tran family landed in Des Moines and soon moved to Carroll. Ngoc Phu Tran laughs as he remembers the ride with his sponsor from the airport: "He talked a lot, but I didn't know what about," says Tran, recalling the initial language barrier. "But after one month, I learned a lot."

The Tran family has lived for 39 years now in Carroll, where Ngoc Phu is a longtime employee of Pella Doors and Windows. He and his wife, Y Thi, met in Iowa, and their daughters, Diane and Donna, 04BA, both graduated from the UI. Appreciative of the sacrifices her parents made so she and her sister could have a better life, Diane Tran says, "I'm pretty proud of them because it's difficult to change your life and raise children halfway across the world."

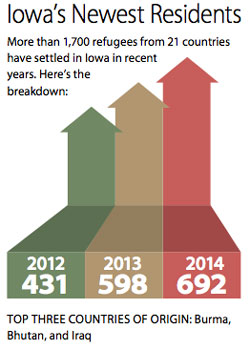

SOURCE: OFFICE OF REFUGEE RESETTLEMENT, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

SOURCE: OFFICE OF REFUGEE RESETTLEMENT, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

A second-generation Vietnamese-American, Tran recently decided to move from Minneapolis to Carroll as an orthopedic surgeon. "Not a lot of people feel the obligation to be a doctor in a small town because it's not as lucrative–but I want to serve the town that raised me," says Tran, still grateful for Ray's decision three decades ago. "To me, Iowa is my home."

Following the Tai Dam relocation, Ray continued to advocate for Southeast Asian refugees, playing a fundamental role in shaping modern U.S. resettlement policy and procedure. The governor's task force later became the Iowa Bureau of Refugee Services, which until 2010 was the only state government organization certified by the U.S. State Department as a resettlement agency. Today, it coordinates and oversees all refugee services in the state, primarily focusing on providing employment opportunities to the state's newest residents.

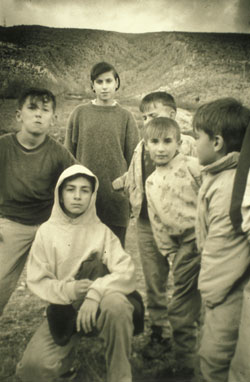

ABOVE: While assisting refugees during the Yugoslav Wars, Iowa City native Amy Weismann helped organize activities such as soccer, gardening, and photography classes. One of the children learning photography took this picture of his friends and fellow Bosnian refugees in the city of Mostar.

ABOVE: While assisting refugees during the Yugoslav Wars, Iowa City native Amy Weismann helped organize activities such as soccer, gardening, and photography classes. One of the children learning photography took this picture of his friends and fellow Bosnian refugees in the city of Mostar.

By the early 1990s, Iowa resettlement among Southeast Asians began to dwindle, while the number of Eastern European refugees from Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, and the former Soviet Union rose. Their struggle moved then-Bryn Mawr college student Amy Weismann, 00JD, to action. Driven by a youthful desire to "be part of social change," Weismann bought a plane ticket to Pula, Croatia, where she volunteered at a Bosnian refugee camp.

An experience intended to last two weeks turned into two years. Weismann helped with aid distribution, taught English, cared for refugee children, and coordinated international volunteers. She began to consider a career in social justice that would one day lead her to become assistant director of the UI Center for Human Rights. Little did she know at the camp, she'd also meet her husband, Amir Hadzic.

Hadzic grew up in Sarajevo, a religiously diverse city in the former Yugoslavia that hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics. As a high school student and athlete, he took pride in participating in the opening ceremony and translating for the U.S. team. Hadzic later became a successful professional soccer player, drawing crowds of admirers as a member of the FK Željeznicar Sarajevo team.

Sadly, within a decade of the Sarajevo Olympics, war broke out and Hadzic went from signing autographs to collecting rainwater to flush his toilet. Following Yugoslavia's first free elections in 1990, nationalists who promoted ethnic cleansing took power. Thousands of Sarajevans lost their lives to genocide when Serb forces took the city under siege, bombarding and shooting at civilians. As the country's infrastructure fell apart, Hadzic survived four harsh winters without gas or electricity–and with limited food and water. He chopped furniture and burned shoes to keep warm. "You'd wake up," he says, "and not be sure if you'd be alive the next day."

A close brush with death came during a conversation with his neighbor outside a local hospital. Five seconds after the two parted ways, a bomb tore apart the building. Devastated and confused, Hadzic rested his hand on a standing wall, only to discover it soaked in flesh and blood. His neighbor had not survived, and Hadzic fully realized he wouldn't either if he didn't find a way out of his homeland.

In December 1994, Hadzic dared to escape. He crawled through a dank, cramped tunnel dug underneath the airport that led outside of Serbian-controlled territory. A guide led him on a two-and-a-half-hour climb over Mount Igman–a struggle even for an athlete like Hadzic. After crossing the Croatian border, Hadzic spent six months living in the Pula camp, the converted Yugoslavia military barracks where he met Weismann. He joined a local soccer team to earn money to help his family back in Sarajevo, and developed an affection for Weismann while helping her organize a refugee children's soccer camp.

With his refugee status set to expire in July 1995, Hadzic still had not found a permanent home. Fortunately, he was approved to move to New York City to live with his cousin through the recently opened U.S. Bosnian resettlement program. As he took his first glimpse at the Statue of Liberty, Hadzic basked in his newfound freedom. He was familiar with the Emma Lazarus poem, The New Colossus, but the words inscribed on the iconic statue never rang more true for him than at that moment: Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses, yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore, send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door.

Mak Suceska, 10BA, and his family similarly escaped danger in the former Yugoslavia. Until recently, Suceska worked for the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants–one of two remaining resettlement agencies in the state. In 2015, USCRI served more than 500 people from places as far-flung as Myanmar, Eritrea, and Afghanistan–providing services that include English classes and career counseling. The agency's goal is for clients to be self-sufficient within 90 days, bringing much-needed stability to refugees upended by the ravages of war. "Some people think refugees have a freeloading mentality," says Suceska, "but no one who has traveled hundreds of miles to flee a war-torn area for somewhere they've never been to is lazy. They have a good work ethic to provide for their families. They want to work for a better life and become citizens, business owners, and active members of society."

Suceska says that many Americans also mistakenly confuse refugees with immigrants, including those who enter the country illegally. Unlike immigrants–who often come to the U.S. for better educational or economic opportunities–refugees are defined by the United Nations as people with a "well-founded fear" of persecution in their country of origin due to race, religion, nationality, social group, or political opinion.

Time will tell how the U.S. responds to the latest wave of Syrian refugees. While America is known for being a country of immigrants, the refugee resettlement program has never been popular among the general public. According to a recent Gallup poll, 60 percent of Americans oppose President Barack Obama's plan to take in at least 10,000 Syrian refugees. In a post-9/11 world, many are fearful that a terrorist could exploit the system to enter the country, as one of the Paris attackers did. Already, 33 state governors–including Iowa's Terry Branstad, 69BA–have declared their opposition to the proposal. "We must continue to have compassion for others, but we must also maintain the safety of Iowans and the security of the state," Branstad said in a statement. "Until a thorough and thoughtful review is conducted by the intelligence community and the safety of Iowans can be assured, the federal government should not resettle any Syrian refugees in Iowa." Although domestic terrorism fears fuel the current opposition to refugees, Gallup polling since the 1930s reveals nearly identical disapproval rates for taking in Europeans during the World War II-era and Vietnamese after the Vietnam War. Indeed, Ray faced political opposition in his decision to welcome Southeast Asian refugees to Iowa. Protestors wrote the governor to share their concerns about Iowans losing jobs to refugees and about state tax dollars going towards resettlement.

PHOTO: MICHAEL NOBLE JR. © 2015 THE GAZETTE

CongoReform Association Executive Director Boumedien Kasha offers a driving lesson to Leocadie Manizanye in the parking lot of Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids.

PHOTO: MICHAEL NOBLE JR. © 2015 THE GAZETTE

CongoReform Association Executive Director Boumedien Kasha offers a driving lesson to Leocadie Manizanye in the parking lot of Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids.

Boumedien Kasha, 15LLM, recognizes the many obstacles that refugees face as they chase the American dream. Once a successful lawyer in the Congo, he had to leave behind his country and career after being persecuted by the government for his human rights advocacy. Kasha received asylum in the U.S. through the assistance of the UI College of Law's legal aid services and now uses his experience to help more than 500 Cedar Rapids and Iowa City-area refugees and immigrants adjust to American life. He launched a nonprofit organization called the CongoReform Association, where members assist newcomers of all backgrounds with everything from airport transportation to communicating with their children's teachers.

Similarly, Hadzic has dedicated himself to giving back to the community that gave him a fresh start. Hadzic later reconnected with Weismann and the two decided to marry and begin their life together in Iowa City. He received his American citizenship after five years in the United States, and, in 2002, witnessed the war crimes trial of Serbian President Slobodan Miloševic, who was largely responsible for Sarajevo's suffering. After that moment, Hadzic says, "Everything came full-circle, and I could finally move [forward]."

Today, Hadzic serves as the soccer coach at Mount Mercy University and Xavier High School in Cedar Rapids, as well as the assistant director of international recruitment and integration at Mount Mercy. Under his leadership, Xavier has earned four new state championships and Mount Mercy has not only qualified for a national tournament, but also enjoys a more culturally diverse campus. With 34 players from 17 countries, the Mount Mercy team has accepted students from traditionally adversarial nations and transformed them into teammates and best friends.

Weismann–who recently taught a UI class on "Refugee Lives and International Law" and also organized the "Refugees in the Heartland" conference where Quinn spoke–sees her husband's success story as emblematic of the can-do spirit that refugees often bring to America.

"We're stronger when we're bold and courageous in our efforts to [align] to our ideals, which have always included welcoming those seeking freedom and safety," she says. "There's very strong evidence that refugees and immigrants contribute economically, culturally, and in every other way to our country. We receive a lot more than we give."

How You Can Help

- Welcome refugees to the community.

- Volunteer with local resettlement agencies, faith groups, schools, and nonprofit organizations that assist refugees.

- Donate items needed by refugees to supporting organizations.

- Fundraise to benefit assisting agencies.

- Teach English as a second language.

- Employ local refugees or be a job coach.

- Learn about and raise awareness of refugee issues.

Resettlement Process 101

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) makes every effort to help refugees integrate into the country of their asylum or return to their native land once conditions improve. If neither is an option, then refugees may be resettled in a third nation.

Only refugees referred by the UNHCR or an American embassy may apply for resettlement in the U.S. These refugees must undergo one of the world's most extensive interviewing, screening, and security clearance processes by agencies such as the UNHCR, the U.S. Department of State, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Priority is given to candidates whose lives are most at risk and have no other options; groups of special concern to the U.S., which include the former Soviet Union, Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Iran, Burma, and Bhutan; and people with close relatives already in America.

In addition to these screenings abroad that check for criminal backgrounds, security concerns, polygamy, smuggling, previous deportations, and misrepresentation of facts, refugees approved by DHS also undergo a medical examination. Then a Resettlement Support Center and the International Organization for Migration arrange the refugee's travel to the U.S. Prior to departure, refugees must sign a promissory note to repay the U.S. for their travel costs.

Upon arrival in the U.S., refugees are greeted by a representative from an American non-governmental resettlement organization. These groups–such as the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, Lutheran Immigration and Relief Services, Catholic Charities, and Jewish Family Service–provide resources for the first 90 days to help refugees adjust to life in their new community and become self-sufficient.

The entire resettlement process typically takes between 18 and 24 months. Refugees may apply for Lawful Permanent Resident status after one year in the U.S. and citizenship after five years.