I

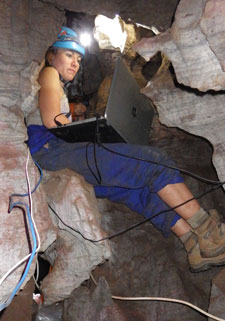

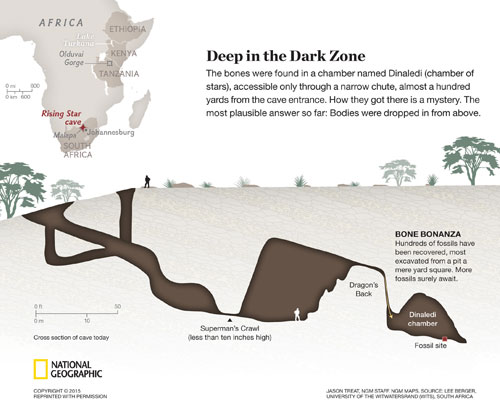

nside a remote dolomite cave in the South African plains, K. Lindsay Eaves Hunter begins a dangerous and difficult descent into utter darkness. She creeps on her belly through a narrow passage called the Superman Crawl (so named because explorers must turn their heads to the side and keep an arm outstretched), climbs a jagged ledge with steep drop-offs known as the Dragon's Back, and squeezes down a 40-foot long chute with a seven-inch pinch point—all to expose the secrets of a secluded underground chamber.

Earlier that morning, Hunter arose at 5:30 inside a military tent baked by the beating sun. The coolness of the cave now offers welcome relief, and she treads on bare feet in the chamber to avoid harming fossils and crushing the past into dust. The UI-trained paleoanthropologist spends the next eight hours crouching over a square-meter excavation site, first documenting the area with a handheld, 3D white light strobe scanner and a forensic camera. Then, using toothpicks, small paintbrushes, and plastic spoons, she meticulously brushes away dirt from bones to unveil a scientific breakthrough that captured the world's attention earlier this fall.

Hunter, 04MA, was one of six "underground astronauts" chosen two years ago for a high-profile expedition to help unravel the mysteries of humanity deep within the Rising Star Cave, 25 miles northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa. As part of a worldwide team of scientists, she was among the first to unearth evidence of an entirely new hominin species—one with a puzzling mosaic of modern human and ape-like features.

The region has already been celebrated as the Cradle of Humankind UNESCO World Heritage Site for being the home of around 40 percent of the world's known hominin fossils. But just this past September, the Rising Star team made international headlines when it revealed details of monumental new fossil discoveries made inside the cave. In a live-streamed press conference at Maropeng, the Cradle of Humankind's official visitor center, expedition leader Lee Berger formally introduced the world to Homo naledi. The news, which appeared in the scientific journal eLife and graced the cover of the October 2015 National Geographic, sheds fresh light on the diversity of our genus Homo.

PHOTO: ELLEN FEUERRIEGEL

PHOTO: ELLEN FEUERRIEGEL

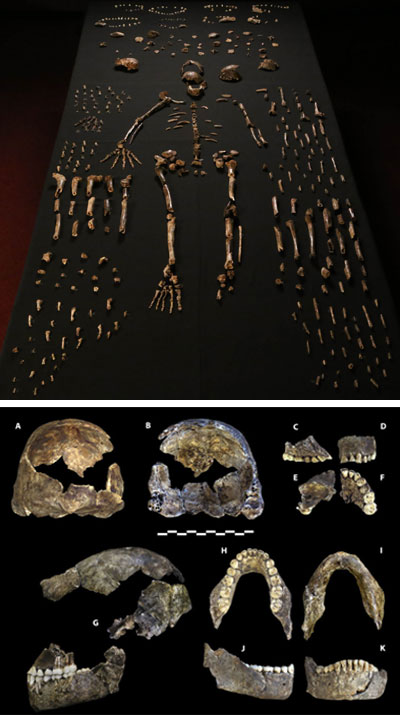

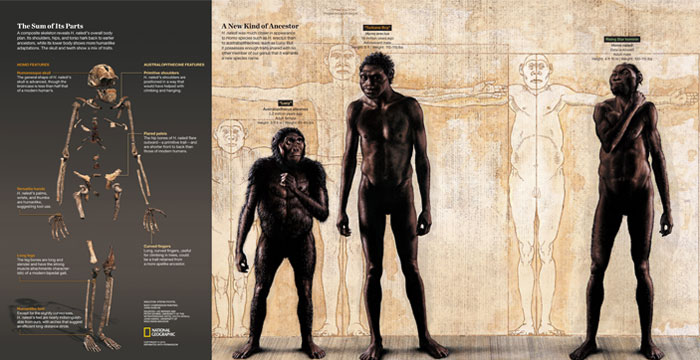

The Rising Star expedition, sponsored by the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, the National Geographic Society, and the South African Department of Science and Technology/ National Research Foundation, led to the excavation of more than 1,500 fossils belonging to at least 15 individual skeletons ranging from infant to elderly. Named naledi, which means "star" in local African languages, the species appears to have a small, round head and a chimp-sized brain—a third the size of a modern human brain. Homo naledi also had a more ape-like torso and shoulders, as well as long curved fingers useful for climbing trees and rocks. Otherwise, the skeletons bore more resemblance to a five-foot tall, 100-pound human than a modern ape. This particular combination of primitive and contemporary traits has never been seen before in one hominin species, which led to the new classification.

"Instead of keeping these discoveries veiled behind locked doors, we have tried to bring them to the public in ways that will drive greater curiosity and engagement with science."

Scientists have yet to determine exactly how long ago Homo naledi lived, how it wound up in the isolated chamber, or where it fits into their understanding of human evolution. Regardless, the find has already drawn widespread attention as the largest collection of hominin fossils ever discovered from a single site in Africa.

Berger, a research professor in the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand and a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence, had reason to believe the Rising Star cave system held valuable insights into early human life beneath its dripping stalactites. Only five years earlier, he found several nearly complete hominin skeletons at Malapa Cave, a mere 10 miles from Rising Star. Berger dated the skeletons at about two million years in geologic age and classified them as a new species: Australopithecus sediba. The australopith, sharing more features with the famed apelike Lucy skeleton than with the tool- and fire- making Homo erectus, was the first new hominin species discovered in South Africa in decades. While many anthropologists had already shifted their human origins research to the Great Rift Valley in East Africa where Lucy was excavated in 1974, Australopithecus sediba renewed Berger's efforts in South Africa. He began asking local cavers to keep their eyes out for fossils.

The Rising Star expedition emerged on a tip from two recreational cavers, Steven Tucker and Rick Hunter, who accidentally stumbled upon the cave's unexplored Dinaledi Chamber one lucky Friday the 13th in September 2013. After slipping down a vertical chute that led to an area teeming with fossils, the cavers took photos of a particularly striking lower jawbone lying on the ground. It appeared to be a hominin—a member of the bipedal primate group that includes the genera Australopithecus and Homo. The cavers then showed Berger, who soon created a Facebook post that would send Lindsay Hunter on one of the wildest adventures of her life.

In October 2013, Berger placed an ad on social media in search of archaeologists or paleontologists willing to fly to South Africa and participate in a mysterious short-term project. The ad specified that applicants must be small, fit, non-claustrophobic, and experienced in climbing and caving. Hunter, a former UI biological anthropology Ph.D. candidate, first forwarded the post on to a friend. However, she began to realize that her personality and skills perfectly fit the qualifications. Never one to experience science solely from the sterile lab, Hunter liked to get her hands dirty in the field. Plus, the curious daredevil in her was intrigued. "The ad was reminiscent of that for the ill-fated Shackleton Antarctic Expedition, promising adventure and honor, but uncertain success (and survival)," she says. "That's only going to appeal to a certain kind of person, of which I am one."

"Something weird [went] on at that site. [The placement of Homo naledi in the hard-to-reach chamber] does beg explanation, but I'm not ready to do so with burial or fire."

Within a week-and-a-half, Berger had heard from nearly 60 applicants from around the world. He chose the six most qualified scientists—including Hunter— to form what turned out to be an all-female Rising Star caving team. Hunter squealed with joy when she received her acceptance email, rereading it over and over. As she recalls in the recent NOVA and National Geographic Dawn of Humanity documentary, "My brain was just like an explosion of glitter and confetti. It was like every best birthday, Christmas, Hanukkah...everything all at once."

SOURCE: LEE BERGER, WITS, PHOTOGRAPHED AT EVOLUTIONARY STUDIES INSTITUTE

SOURCE: LEE BERGER, WITS, PHOTOGRAPHED AT EVOLUTIONARY STUDIES INSTITUTE

The international members of the Rising Star crew arrived in South Africa weeks later, prepared to face some of the most challenging and dangerous conditions ever encountered in the search for human origins. For the team's safety, local cavers installed lights, a phone intercom, and communication and power cables along the cave route. The team used harnesses to maneuver the Dragon's Back, but had to free-climb the narrow chute. Cameras allowed Berger and dozens of other crew members to watch the excavating scientists' work from a command center outside the cave.

That November, Hunter's teammate Marina Elliott became the first of the excavating scientists to enter the chamber and begin the process of recovering the mandible that first lured Berger to the cave. From the command center, tears fell from Hunter's eyes as she watched Elliott inch her way into a sea of bones and discovery.

On the first day, the crew recovered the lower jawbone for closer inspection. The team bagged, labeled and bubble-wrapped the fossil; placed it in a protective plastic container secured in another bag; and sent it up through a pulley and courier system for examination. Immediately, the scientists knew they had found something special. While the cavers' early photos suggested the jawbone belonged to an australopith, a closer look at the mandible revealed more human- sized teeth.

For many anthropologists, the jawbone alone would've been a lucky find. But the Rising Star team recovered more than 1,200 fragments in 21 days, with another 10-day excavation in March 2014 lifting that total to 1,550 fossils. In the history of paleoanthropology, only the El Sidrón Neandertal cave in Spain and the Sima de los Huesos cave, another Spanish site featuring remains directly ancestral to the Neandertals, contained a larger treasure trove of fossil hominin bones. Experts say such extensive bone collections are key to understanding morphological evolution, allowing them to tell whether subtle differences among the same species are the result of normal variation or due to an incidental or pathological reason, such as a birth defect.

"My brain was just like an explosion of glitter and confetti. It was like every best birthday, Christmas, Hanukkah... everything all at once."

With every new fossil, Hunter's preconceptions of finding a few fragments of an Australopithecus were tossed aside. She and her fellow anthropologists only anticipated a single skeleton, but each time Hunter removed a bone, she'd find a new one beneath it. By the second week, the team had run out of room in the preservation safe—excavating more fossils than had been found in all of southern Africa in the past 90 years.

By the November dig's third week, the Rising Star crew prepared for the final excavations. At the back of the chamber, the scientists had previously spotted the outline of a cranium and decided to save the complex extraction for near the end. When it was finally loosened from the dirt, the team lined up along the path to the cave's exit, passing the bag with the skull inside from one caver to another. For a moment, Hunter held the groundbreaking discovery in her hands as she balanced precariously along the precipice of the Dragon's Back. When she finally emerged from the cave, Berger's entire crew erupted into cheers and applause.

For the first time in possibly millions of years, Homo naledi had left the cave. But the biggest mystery was how it arrived there in the first place. Surprisingly, virtually no animal bones were found in the Dinaledi Chamber. Neither were any stone tools or remains of meals that would indicate they lived there. The evidence suggested that the cave only ever had one entrance, offering a dark and treacherous journey challenging even for the modern human equipped with artificial light. "We explored every alternative scenario, including mass death, an unknown carnivore, water transport from another location, and an accidental death in a death trap," says Berger. "We were left with intentional body disposal by Homo naledi as the most plausible scenario."

Some scientists like UI anthropology professor Robert Franciscus are skeptical of this interpretation, which would be quite advanced social behavior for a species that had a brain the size of an orange and likely hadn't discovered fire to light the path. However, until anthropologists determine how old the fossils are, they'll face difficulty in arriving at another conclusion. "Something weird [went] on at that site," says Franciscus, who served as Hunter's graduate adviser. "[The placement of Homo naledi in the hard-to-reach chamber] does beg explanation, but I'm not ready to do so with burial or fire."

PHOTO: UNIVERSITY OF WITWATERSRAND

At the Rising Star workshop in May 2014 at the University of the Witwatersrand, these scientists (including Jill Scott and Myra Laird, pictured third and fourth from the left in the third row) became the first to analyze the features of Homo naledi.

PHOTO: UNIVERSITY OF WITWATERSRAND

At the Rising Star workshop in May 2014 at the University of the Witwatersrand, these scientists (including Jill Scott and Myra Laird, pictured third and fourth from the left in the third row) became the first to analyze the features of Homo naledi.

Discoveries made in South African caves are notoriously challenging to date. Because the fossils weren't found dispersed with animal bones from the same time period, scientists can't calculate a faunal age. In caves, it's also tough to find clearly defined sedimentary layers, with rock collapses, rushing water, and burrowing animals potentially interfering with the original positioning. Plus, these fossils weren't found neatly tucked between layers of rock, but rather lying on the surface or hidden in shallow, mixed sediments. The team has already tried determining the age of the fossils three times to no avail and is currently working on other dating methods that have proved to be difficult and time-consuming.

Without dates, scientists don't know how to interpret Homo naledi's apparent behavior of disposing of its dead or where exactly to place it within the hominin family tree. Their biggest question is whether the species fits in the transitional time period between the end of the Australopithecus and the emergence of the genus Homo believed to have occurred more than two million years ago.

"Over a century after [the discovery of Neandertals], we are still learning new and surprising things about their anatomy and ways of life. I hope the questions never stop."

While much remains to be understood about Homo naledi, scientists already have a good head start. Major finds such as this one often take decades before they are fully revealed to the public. Yet Berger was able to cut down on the time between discovery and publication by hosting a May 2014 workshop at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, where 30 early-career researchers and experienced scientists dedicated five weeks to fossil analysis and scientific paper-writing [see sidebar.]

The Rising Star team has already published four papers this past fall about Homo naledi in the peer-reviewed, open-access scientific journals eLife and Nature Communications, with around a dozen more anatomically-specialized papers expected in the coming months. Says John Hawks, a University of Wisconsin-Madison paleoanthropologist and Rising Star co-author in a post for the news blog The Connection, "The open-access philosophy has driven our work on Homo naledi from the beginning. Instead of keeping these discoveries veiled behind locked doors, we have tried to bring them to the public in ways that will drive greater curiosity and engagement with science."

Such methods have rapidly led scientists to more insights on human evolution. After examining Homo naledi's astonishingly small skull, they have moved even further away from the famous but misleading "March of Progress" illustration that suggests a linear progression and instead toward a more complex model with many experimental side branches. Ever since the 2003 discovery of Homo floresiensis (known as "the hobbit"), which lived as recently as 12,000 years ago, scientists have been especially careful not to assume that a primitive-looking skeleton is as old as it appears. Homo naledi's mosaic anatomy further serves as a sign of caution for those trying to extrapolate on a species' appearance based on a single piece of fossil. Franciscus says, "Homo naledi is crucial, because we're beginning to realize how different parts of the body seem to evolve at different rates and times in the genus Homo."

Already, Homo naledi is rewriting anthropology textbooks and has reinvigorated students passionate about scientific discovery. Lindsay Hunter, the wife of cave explorer Rick Hunter and soon to be a Ph.D. candidate at the University of the Witwatersrand, has been working on creating interpretive materials on Homo naledi to appeal to schoolchildren and the general public. "I think [the find] has helped young women to imagine a more adventurous role in science for themselves, though I hope that [all children] will see that this is an exciting career path and one that they can succeed in," she says. "Over a century after [the discovery of Neandertals], we are still learning new and surprising things about their anatomy and ways of life. I hope the questions never stop."

In the two years since its unearthing, Homo naledi has made an irrevocable impression on the world of paleoanthropology. Not unlike the stars in the night sky that inspired its name, Homo naledi will continue to illuminate the path to a greater understanding of early human history. After all, as Berger pointed out, "This chamber has not given up all of its secrets."

More on Homo naledi

To read the scientific papers published in eLife, visit

http://elifesciences.org/content/4/e09560 and

http://elifesciences.org/content/4/e09561.

A New Approach to Science

PHOTO: JOHN HAWKS

Myra Laird (left) and Jill Scott (second from left) were among the six early-career scientists who made up the team that examined the cranium

and mandible of Homo naledi.

PHOTO: JOHN HAWKS

Myra Laird (left) and Jill Scott (second from left) were among the six early-career scientists who made up the team that examined the cranium

and mandible of Homo naledi.

Two Iowa alumnae mentored by UI anthropology professor Robert Franciscus—Myra Laird, 10BA, 10BS, a New York University anthropology doctoral candidate, and Jill Scott, 09MA, a UI anthropology doctoral candidate—participated on an international team of scientists who were the first to analyze the features of Homo naledi.

Much of the anthropology community was already following the Rising Star expedition through social media when team leader Lee Berger asked in January 2014 for early-career scientists to attend a May 2014 workshop at South Africa's University of the Witwatersrand. It was a rare opportunity for young anthropologists to join more established scientists on such a high-profile project. Laird and Scott immediately applied and were later accepted for the assignment.

Laird packed up casts of early and modern primates from NYU's collection along with primate cranial data, while Scott brought along the extensive data she'd collected from skeletons in museums across Europe. They joined some of the field's brightest minds at the university's new Phillip V. Tobias Fossil Primate and Hominin Laboratory, a secure vault built to accommodate one of the world's largest hominid collections. Several thousand fossils are stored there, including the famous Taung Child, the skull of a young Australopithecus africanus that helped direct attention to South Africa as a place to search for insights into early hominin life.

One workshop participant referred to this windowless room, now brimming with the world's most important hominin fossil finds, as "nerd heaven." The scientists divided into teams based on their anatomical area of expertise to compare all of the discoveries of the past with the skeletal features of Homo naledi. Laird and Scott both focused on Homo naledi's mandible and cranium, which would prove crucial to understanding the life of the new species. The teammates examined the teeth of Homo naledi to determine the ages and diets of the various individuals recovered, as well as their skulls to reveal a brain size that was surprisingly small in comparison to other members of the genus Homo.

The Rising Star team has been unique in its transparent and timely approach to scientific research. Laird says the open-access publications and fossil models will help move the field of anthropology forward and bring unprecedented opportunities to students and young professionals. While professionally-made fossil casts can be expensive and take months to be completed, anyone with access to a 3D printer can now produce models of the fossils in about a day.

Scott similarly appreciates how such accessibility invites anyone to do further analysis and come up with their own conclusions. She says, "I think it's a positive model, and I sincerely hope others will follow it to some extent."