A man boards the crowded plane and searches for his row. About 5-foot-10 and 300 pounds, he's classified as a "passenger of size" and has already purchased two airline tickets because he can't fit in the 17-inch space between the armrests. Now, he faces the long walk to his seats. Sweat beads form at his brow as he squeezes along the aisle, keenly aware of the stares from other travelers.

He knows the judgmental thoughts running through their minds.

Please don't let him sit next to me.

How can someone let himself go like that?

He should skip the in-flight meal.

If only the solution to his weight problem were that easy.

For years, obesity has been labeled a behavioral disorder—the result of poor lifestyle choices that place blame squarely on a big person's shoulders. Now, years of research into the No. 1 public health problem in the developed world paints a different picture. Contrary to popular opinion, mounting scientific evidence proves that the factors behind an epidemic that impacts 35 percent of the U.S. population go way beyond what we eat and drink.

Undoubtedly, personal behavior and choices contribute to the problem, and people have to take accountability for their lives. But, experts now realize that the obesity epidemic involves a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, biologic, community, and socioeconomic factors that diet and exercise alone will never solve. In fact, just last year, the American Medical Association classified obesity as a disease—revolutionizing the way the medical community approaches the issue.

In their resolution, members of the AMA boldly stated: "The suggestion that obesity is not a disease but rather a consequence of a chosen lifestyle is equivalent to suggesting that lung cancer is not a disease because it was brought about by [the] individual choice to smoke cigarettes."

University of Iowa professor of internal medicine Allyn Mark, 57BA, 61MD, 67R, 69F, agrees that obesity is not simply a matter of lack of willpower and personal choices. "Public perception remains that the obese eat too much and exercise too little and are therefore responsible for their own condition," he says. "It's not that simple. There are strong contributors largely beyond the ability of the individual to control and that influence why some people develop obesity while others remain lean."

Multidisciplinary Efforts

At the UI, Mark serves as co-director for the Obesity Research and Education Initiative (OREI), established in 2011 as one of President Sally Mason's intercollegiate initiatives to address grand, global challenges of the 21st century—in this case the prevention and treatment of obesity through new faculty appointments, millions of dollars in grant research, educational programs, and outreach.

A chronic, complex disease like obesity requires a sustained and multi-faceted response, Mark says. And so OREI brings together faculty in basic biomedical research focused on genetic and biologic regulation of appetite and metabolism, and in behavioral sciences with an emphasis on nutrition, physical activity, psychology, economics, and community-based research. "Diet and exercise will always be good for you, but we know that's not the complete answer because many people who lose weight regain it," Mark says. "No single approach will solve the problem."

Over the past 30 years, obesity has steadily marched toward its current crisis proportions. Today, one-third of the American population meets the classification for obesity—defined as a body-mass index or BMI (a weight-height calculation) of 30 or higher, although some experts question the measurement's accuracy. The problem spans age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status. So far, effective prevention and treatment remain elusive. Beyond bariatric surgery, reserved for the morbidly obese with secondary complications such as uncontrolled diabetes, little can be done for mild to moderate cases. Even fewer options exist for childhood obesity, which, in Iowa alone, has more than tripled in the past three decades.

Obesity-related conditions such as heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, cancer, diabetes, and depression are more than life-threatening—they also contributed to a staggering economic burden of $147 billion in medical costs, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) most recent statistics in 2008. Other agencies report more recent figures of $190 billion. Beyond the physical aspects, people with obesity suffer from an immense psychological weight that piles on guilt and shame.

As one Experience Project blogger describes in a piece titled "I Am Tired of Being Fat": You stare wistfully at your reflection in the mirror.... The features on your face, no matter how beautiful...are dwarfed by the extra fat .... Your eyes, which may be wide and lovely, look small and particularly deep set in your skull. Your chin is a buoy floating on the sea that is your double chin. The rest of your body is a mishmash of lumps and bumps, protrusions and strange angles that you know you simply cannot hide, regardless of what you wear.

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROWComplex Causes

To understand some of the causes driving the obesity epidemic, Mark points to changes in American culture that create a "toxic environment." Food industry trends support the production and consumption of myriad packaged goods that offer a bountiful harvest of inexpensive, high-calorie, super-sweetened food and drink. In addition, cars, televisions, computers, electronic gadgets, and computer games all promote an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. Many employees and students in offices and schools sit virtually immobile at their desks for hours on end each day. Further, modern suburbia renders neighborhoods less walkable, and the socioeconomic design of certain cities results in "food deserts"—geographic areas lacking easy access to healthy fruits and vegetables. As a result, many people become ensnared in an environment of poor food and less movement.

What enables one person to remain lean in these circumstances, while another constantly fights the battle of the bulge? The secret seems to lie in how their inner genetic landscape reacts to the outer environment. Studies in animals and humans reveal that appetite and physical activity are under strong genetic-biologic regulation. Some people can genetically tolerate or even resist a culture of over-nutrition and under-exercise, while others are genetically and biologically susceptible to obesity. Still others succumb to unexpected or hidden environmental factors substantially beyond their control—like changes in gut bacteria, disordered sleep, or certain medications—that can interfere with the body's hormonal and metabolic functions, leading to weight gain.

As the late diabetologist Elliott Joslin put it: "Our genes load the gun and lifestyle pulls the trigger."

Hot on the trail of the smoking gun, OREI co-director Charles Brenner works to solve the cellular and biochemical basis for weight gain. His research projects investigate specific problems and imbalances along the metabolic pathway, such as why metabolism slows in response to ingesting more food.

From an evolutionary standpoint, Brenner explains, the human body is made to defend against starvation in the face of famine—but not against obesity. When presented with overabundance, features of animal metabolism honed over 500 million years of evolution allow our bodies to pack away and stubbornly hold on to fat. The body will even adapt to resist weight loss, which explains why most dieters regain what they've lost in three to five years. "Although dietary and behavioral therapy are a cornerstone of treatment," Mark says, "their effectiveness over time is limited by biologic adaptations that increase appetite and promote weight gain."

Plus, people evolved to expend energy while hunting or gathering their food. Our ancestors weren't fat because they labored throughout the day for their sustenance—instead of entertaining conference calls while scarfing double cheeseburgers, fries, and large sodas. Our genes remain the same, but our environment has changed.

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW

PHOTO: REGGIE MORROW"We all differ in our sensitivity [to excess food], but virtually all animals are programmed to gain weight in such an environment," says Brenner, also UI professor and chair of biochemistry. "The new type of malnutrition is over-nutrition."

Brenner investigates regulatory systems in which a single cell experiencing over-nutrition shifts its metabolism from burning fuel to storing fat. If scientists can understand the process by which cells slow their metabolism, they may be able to reverse it—whether in the form of a nutritional supplement or drug therapy.

Searching for clues and insights in every system of the human body, other faculty probe science-heavy areas like the neural basis for feeding and disordered eating; endothelial cells and lipid metabolism; neuropeptide function in obesity and drug development; regulation of mitochondrial function in obesity; hypothalamic and hindbrain regulation of appetite; and metabolomics. Such varied pursuits intend to leave no cell unturned.

Says Mark: "Just as advances in the prevention and treatment of heart disease and cancer in the past 50 years have evolved from multiple solutions working in concert—changes in lifestyle, behavior, and environment, new drugs, surgery, and devices—so it is likely with advances in prevention and treatment of obesity."

Practical Approaches

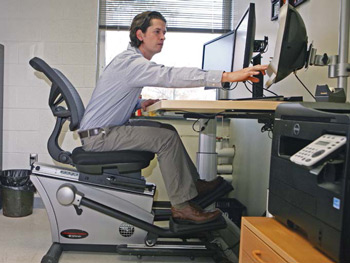

Until safe, effective drug treatments become available, other OREI researchers are looking at practical ways in which people can tackle their weight problems by changing their lifestyles or environment. At Lucas Carr's office in the UI Field House, he pedals away at an elliptical work station that can also transform into a standing desk. An assistant professor in health and human physiology and a new OREI faculty member, Carr focuses his research on leveraging the reality of our modern environment to maximum advantage. Recognizing not everyone can set aside time or resources for an exercise regimen, he wants to pinpoint ways to better design schools and workplaces so that people can naturally and sustainably incorporate extra movement into their days.

In many ways, labor-saving technologies have exacerbated the obesity problem. So, Carr looks at ways technology can bail us out by increasing physical activity. He recently completed a 16-week pilot study at ACT—one of Iowa City's largest companies—that equipped several volunteer employees with a smaller, portable model of his elliptical desk called the activeLife Trainer. The device allowed the workers to sit and type while pedaling their legs. An iPod application tracked each participant's time pedaled, which ranged from 15 minutes to three hours per day. Even a few extra minutes of movement equals success to Carr, and he's currently evaluating whether the desks increased participants' focus and productivity.

When Carr offered ACT employees the option of keeping their desks at the end of the four-month project, 70 percent accepted, while several others have inquired about purchasing the machines on their own. But workers don't necessarily need a mini-elliptical to become more active at the office. Small changes like opting for the stairs instead of the elevator, parking farther away from buildings, and taking even two-to five-minute walking breaks can produce big results.

Other projects find solutions on the home front. At the UI Children's Hospital, Carr and UI director of nursing research Sharon Tucker collaborate with pediatricians Vanessa Curtis and Thomas Scholz, 88R, 91F, on an initiative that tests innovative behavioral strategies designed to help obese children lose weight. With 30 percent of Iowa's children in need of weight control, doctors in the hospital's childhood cardio-metabolic clinic help elementary school kids, tweens, and teens with obesity-related problems such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and liver disease. For these at-risk youth, health and longevity depend greatly upon the habits of their families.

The team plans to recruit 150 families from the clinic to participate in an experiment that combines technology with personal health coaching to create lasting lifestyle changes. All family members will keep online food diaries to track their food intake and will wear FitBit "smart" devices to record their physical activity. They'll also meet with UI student health coaches who'll use "motivational interviewing" techniques to uncover specific barriers to wellness. Based on the premise that lecturing people about their health isn't effective, these conversational strategies encourage people to identify their social, emotional, habitual, and economic barriers to weight loss. Questions divine the driving forces behind family choices. What's in the pantry? Can they afford healthier foods? What time do they get home from school and work? Do they have health care? Can they prepare meals in advance to make time for a family walk? Is there anything they are unwilling to change? From their answers, the UI students and study participants will brainstorm realistic solutions.

While OREI is the focus for much work on obesity, other campus partners also work to tackle the issue. The UI Nutrition Center in the College of Public Health provides nutrition counseling and dietary assessment for various research studies and supports projects aimed at improving wellness—with a special interest in those that address the obesity epidemic at the community level.

With a firm belief that healthy habits begin in childhood, Director Linda Snetselaar, 75MS, 83PhD, and her colleagues currently work in the Muscatine and Fort Dodge, Iowa, school systems to implement wellness programs. Another outreach project evaluates the effectiveness of a new nutritional scoring program called NuVal. Recently adopted by the Iowa HyVee grocery stores, NuVal labels foods on a score of 1-100, with healthier foods receiving a higher score. Through analyzing store receipts, investigators will see if this program effectively persuades shoppers to purchase healthier foods. "In other 'addictions,' a person can just stop. You can stop doing drugs, but you can't stop eating because your life depends on it," Snetselaar says. "We must see where we can make sustainable improvements in our communities."

Additionally, researchers like Barbara Baquero and Edith Parker with the college's Prevention Research Center for Rural Health oversee a major CDC-funded Ottumwa-based program focused on promoting healthy lifestyles in that community.

Back on the UI campus, another OREI-affiliated research project tests ways to help UI students eat better at residence dining halls—without any conscious effort. At Burge Hall earlier this fall, the "Mindlessly Eating Better" experiment instituted subtle changes in an effort to subconsciously influence better food selections without restricting choices. Fruit bowls now abound in the dining hall, desserts are smaller, and signage instructs students that "Pasta goes great with vegetables—they are this way!" Sample plates of a balanced meal based on that day's menu provide students with visual clues about what to choose. Summing up the overall intent, project co-investigator and UI assistant professor of internal medicine Helena Laroche says, "We're just hoping to nudge students in the right direction."

Hopeful Future

In an effort to support a healthy campus community, the UI's liveWell program offers faculty and staff incentives, such as a discount on memberships to the Campus Recreation and Wellness Center or cash rewards for completing a personal health assessment. Such policies from employers and other entities capable of making real change will make a huge impact, Laroche says, half-jokingly suggesting that the government subsidize broccoli farmers to make fresh foods more affordable. Through her own outreach project with low-income families in Des Moines, Laroche can attest: "If you're about to lose your apartment or you can't heat your home, you're not going to prioritize diet and exercise."

Just as pharmaceuticals to tackle obesity are a long way off, so government policy and individual lifestyle shifts will be slow to take effect. Still, Laroche points out that some urban areas like Philadelphia and New York are experiencing a plateau of childhood obesity, thanks in part to establishing supermarkets in food deserts and investing in green spaces that encourage exercise. Perhaps more places will follow the example of Somerville, Massachusetts, which launched a 15-year strategy called "Shape Up Somerville" to build and sustain a healthy community. Already, some U.S. public school systems have improved their lunch offerings by adding more whole fruits and vegetables, while "fresh and local" organic food movements gain traction across the country. Industry analysts estimate that American consumers spent $28 billion on organic food sales in 2012, an 11 percent increase from 2011.

Such gains suggest a hopeful future. Still, it will take time and effort to change medicine, culture, and human behavior. As Snetselaar says, "Obesity is one of those problems that didn't happen overnight. It's unrealistic to expect that it will go away in the blink of an eye."

But perhaps some of the pain can. Perhaps new medical and scientific understanding of obesity can inspire greater empathy and understanding to lighten the disease's emotional burden, a weight immeasurable by scale—but just as heavy.

For more information click, here.