In the dark wings of the Coralville Center for the Performing Arts, Steven Jepson felt nervous energy surge through his body. He took a deep breath, swung his leg over a small penny-farthing bicycle, and pedaled onto the brightly lit stage.

He navigated carefully around the set, being mindful not to accidentally steer into the orchestra pit, and then lifted his rich baritone voice in the opening notes of a difficult Gilbert and Sullivan piece aptly named the "nightmare aria."

One of the world's oldest musical art forms, opera is also one of the most challenging. In addition to developing a high standard of vocal ability, performers must master projecting their voices—without amplification—over an orchestra. Often, they have to sing in a foreign language or while dressed in cumbersome period costume. And with the days of "stand and sing" opera mostly over, today's performers must also be talented and versatile actors.

Jepson, 82BM, a doctoral candidate in the University of Iowa's opera program, half-jokingly compares the experience to "juggling with an egg, a baseball, and a bowling ball while standing on one leg—and then being thrown a chainsaw."

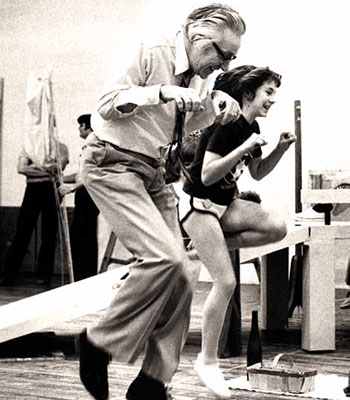

PHOTO: WINSTON BARCLAY

Beaumont Glass and student, 1981

PHOTO: WINSTON BARCLAY

Beaumont Glass and student, 1981

Still, some 400 years after the first work, Jacopo Peri's Dafne, was performed in Florence, Italy, opera faces questions about its relevance in the modern world. Critics accuse it of being out-of-touch, elitist, and boring. Stereotypical notions persist about large women wearing Viking helmets and screeching unintelligible lyrics. Audiences are shrinking and graying (with the average opera-goer around 65 years old), while tickets costing up to a couple hundred dollars each put performances out of reach of many people. As a result, many American professional opera companies struggle financially. Earlier this year, the San Diego opera company faced closure until supporters raised $2.1 million to keep it going.

In addition to those genre-wide woes, the UI School of Music's program has faced struggles since the floods of 2008 swept away its permanent teaching, rehearsal, and production facilities. But, just as Jepson juggled several feats to pull off a spectacular performance in last summer's production of Iolanthe, so the world of opera and the UI Opera Theatre Program are finding creative solutions to those obstacles.

"It's an exciting time," says UI opera director Bill Theisen. "We're beginning a new era of opera theater here in Iowa City."

Theisen's presence itself is a positive sign. The first full-time director for several years, he joined the UI in 2013 after previous stints as a guest artist and interim director. He's looking forward to building the program, a process that will be aided immeasurably by the two new, state-of-the-art facilities (see sidebar) nearing completion to replace the flood-ruined School of Music and Hancher.

Opera began at the UI in 1939 as a collaboration between the theatre and music departments. Its heyday came under the direction of Beaumont Glass, who joined the university in 1980 from the Zurich Opera in Switzerland and over the next 18 years staged Barber of Seville, The Magic Flute, and Boris Godunov. The program's notable former students and alumni include Simon Estes, 86BM, Katharine Goeldner*, 85BM, and Michele Crider, who frequently return to campus to teach master classes or perform.

PHOTO: TODD ADAMSON

Steven Jepson in Iolanthe.

PHOTO: TODD ADAMSON

Steven Jepson in Iolanthe.

The UI continues to attract students who are drawn to a life in this exciting and venerable field, whether as a performer, director, educator, or administrator. Jepson returned to the UI at the age of 51, two decades after completing his undergraduate degree in music. Although he's carved out a successful singing and directing career in Europe, Japan, and the Americas, performing opera (including his signature role as Carmen's Escamillo), choral work, musical theater, and cabaret, he wanted to pursue the doctoral degree that would enable him to teach at the university level.

Through two productions in the academic year and one each summer, the UI program aims to show audiences the magic of a spectacular art form that combines the best of music, theater, and drama. "Opera is arguably the most collaborative art form," says voice professor John Muriello. "All these people who are experts in their field—directors, lighting and set designers, orchestra musicians, and singers—come together. The best opera productions have a real sense of natural, organic flow."

That flow was interrupted in 2008, when floodwaters surged through the UI's arts campus. When Jepson arrived three years later, he found a campus transformed. Voxman Music Building, where he spent countless hours as an undergrad, had vanished—replaced by temporary classrooms and recital halls around Iowa City. Bulldozers and wrecking balls had razed Hancher, also home to treasured memories. Jepson appeared there in his first opera, The Magic Flute, performed with the Old Gold Singers, clambered around backstage to help with sets and lighting, and rehearsed as a trumpet player with the Hawkeye Marching Band.

As demolition of the damaged buildings proceeded, Jepson retrieved a piece of the façade of Clapp Hall, which he cleaned and put on display at his home. Via Facebook posts, he kept friends up-to-date with the sad news: "Hancher is gone." "Clapp is gone." "Voxman is gone."

The loss of those physical structures mirrored the changes that Jepson faced in a 21st-century learning environment, such as online courses and communicating with professors via email. He also had to deal with the disquieting fact that he was not only older than all the other students but also many faculty members.

PHOTO: TODD ADAMSON

Amelia Goes to the Ball, 2013

PHOTO: TODD ADAMSON

Amelia Goes to the Ball, 2013

His age and experience did present advantages, though. He already possessed the self-discipline required to commit to hours of solitary music practice a week, and he didn't have to overcome what Muriello calls "the college slump"—the typical slouched student posture that hampers vocal projection.

Many of the students Jepson performed with or taught as a TA were young enough to be his children. In fact, one was his daughter: Katie Jepson, 14BA, who majored in music and elementary education. Some embarrassing moments ensued when she had to introduce him in class as her dad, but Jepson delighted in the opportunity to direct Katie in an opera and, at her senior recital, co-perform a duet of "Anything You Can Do."

Still, the father-daughter duo symbolizes the worrying generation gap facing opera. As they attempt to find the magic formula to attract younger audiences, opera companies have experimented with various initiatives. In addition to centuries-old classics, they've staged works dealing with more modern characters, events, and issues—such as Nixon in China, Doctor Atomic, and Dead Man Walking.

To overcome the language barrier, they introduced supertitles that display translations of lyrics above the stage. Since 2006, New York's Metropolitan Opera has made a night at the opera cheaper and more convenient by screening live high-definition simulcasts in cinemas around the country and the world. Also in New York, On Site Opera stages shows at non-traditional venues like Madame Tussauds to attract new audiences.

While the UI program doesn't face the same financial pressures as professional companies, it still needs to nurture future fans. Practical measures like making opera more affordable for budget-conscious students are already making a difference. Since 2008, when the university lowered the price of student tickets to $5, the number of students attending opera performances has risen by 30 percent.

The program has to balance audience preferences with the need to put on productions that encourage students' growth and showcase their talents as performers and singers. Theisen plans to stage more contemporary works, saying: "It's the future for opera, and our students will be well-prepared because they're used to doing this kind of work."

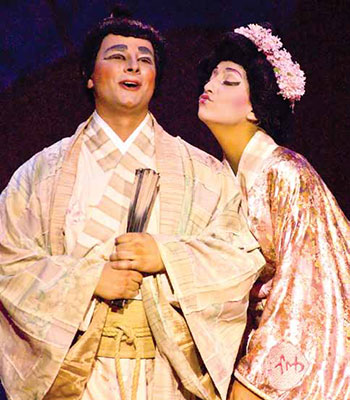

PHOTOS: TODD ADAMSON

The Mikado, 2011

PHOTOS: TODD ADAMSON

The Mikado, 2011

Colorful, high-spirited Gilbert and Sullivan operettas or newer works that bridge the gap between Broadway musicals and opera are part of the UI's efforts to make opera more accessible and less intimidating. Family-friendly performances such as last summer's production of Iolanthe help instill an appreciation of the art form in young fans.

Susan Orhon, the program's marketing director, took her two children, then aged four and five, to see Iolanthe. The youngsters sat spellbound through the entire three-hour opera, with its setting in a magical world of fairies and its hilarious script. A year later, they still chuckle about highlights like Jepson's entrance on the bicycle.

Post-flood venues such as the Englert Theatre downtown also helped bring opera to audiences that may not otherwise have sought it out. In fact, it was at the Englert that Jepson took to the stage this spring for one of his final performances as a UI student: as one of the leads in the production of Die Fledermaus.

He also ended his student career on another high note, earning straight As for his final grades and a GPA of 3.94—"not bad for someone who waited 24 years to go back to school," he laughs.

All that remains to complete is his essay on a long-lost version of a song cycle possibly connected to the 1933 film Don Quixote. Once that's finished, Jepson will return to campus and cross the stage one final time to be "capped" as a doctoral graduate. By that time, the School of Music building and Hancher may be completed—and the curtain will rise on the long-awaited new era for opera at the University of Iowa.

Making Music

With each day of construction, the new School of Music and Hancher draw closer to their estimated completion dates in 2016.

For faculty, staff, and students who've used temporary offices and rehearsal and performance spaces since the floods of 2008, that time can't come soon enough. Although they can never replace the memories forged in the Voxman Music Building, Clapp Recital Hall, and the old Hancher auditorium, the stunning new facilities offer improvements and exciting possibilities.

Conveniently situated at the intersection of Burlington and Clinton streets, the new School of Music offers a downtown location that will make it easier for students to get to their classes and for community members to attend the hundreds of performances and recitals presented every year. Highlights include:

- a 700-seat concert hall;

- a 200-seat recital hall;

- rehearsal spaces for opera, large ensemble, and chamber music;

- an organ performance hall; and

- a music library.

While remaining adjacent to the Iowa River, the replacement Hancher will sit seven feet above the 500-year flood level. Highlights include:

- an auditorium structurally isolated from the rest of the building to ensure ideal acoustics;

- a 1,800-seat, multipurpose proscenium theater;

- space for the music school's scene shop, costume shop, and recording studio;

- a new café; and

- outdoor terraces with stunning views of the river and campus.

Keep up with progress on the two new buildings at www.facilities.uiowa.edu/BuildingforIowa.htm.