PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

Saturated with anger and protest, the foam head is surprisingly light for an object weighted down with history. The blank, dark eyes stare out of a face painted with stars and stripes. Time has gnawed on the perversely patriotic features, leaving pockmarks and scars.

When UI students Evelyn Svendsen and Sam Pottebaum pick it up, they feel an unexpected visceral connection. The two undergrads are engrossed by the macabre object, consumed by questions about its purpose, its creators, and how it ended up in this archival box in the UI Main Library's Special Collections department.

Their reaction is exactly what David McCartney and Tiffany Adrain hope for when they teach "Topics in Museum Studies: The Continuing Role of Real Collections," which ponders whether original, tangible artifacts still have a place in our increasingly technology-driven, information-saturated world.

Today, the university's Iowa Digital Library holds nearly a million items drawn from 100 digital collections—from illuminated manuscripts and antique photos to audio recordings and videos. All areas of university life, along with some highlights from the nation's history, are represented in collections such as the School of Art and Art History graduate archive; the Abraham Lincoln Collection; dentistry college class photos spanning 125 years; the Iowa Sound archive featuring performances and compositions from faculty, students, and alumni; World War II press clippings from Iowa newspapers; and campaign videos from candidates in the 2008 presidential election.

With such a wealth of easily accessible material, why go to all the expense and trouble of keeping the originals?

"Artifacts offer a different experience—that's why people still want to see Lincoln's hat, Dorothy's slippers, and Diana's wedding dress," says McCartney, the university archivist. "It's not a case of digital is good, real is bad. Digital technology is amazing in its ability to revolutionize information-sharing, but it's also easy to forget or minimize the importance of historic objects."

Now in its third year, the class shows members of the Google Generation how even the most unassuming objects share complex stories, inspire curiosity, and forge enduring human connections. Although these young people instinctively turn first to the Internet for instantaneous answers to every imaginable query, even they are surprised by the emotional impact of the real thing.

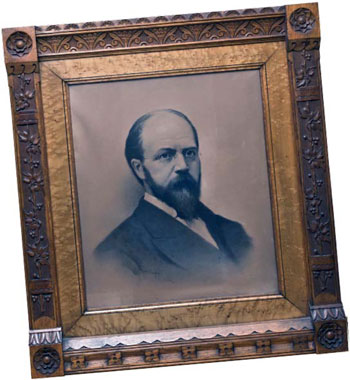

At the start of this weeklong course held over spring break, about a dozen participants choose from a list of objects drawn from various university collections and archives. One young man picks a small aluminum thimble that bears the logo "Home. Happiness. Hoover." A female student is mesmerized by the pencil drawing of a distinguished-looking man with a beard and round glasses—and even more so by the ornately carved oak and maple frame that surrounds the portrait. Another student selects a faded Hawkeye football program from the 1939 Iowa vs. Notre Dame game, complete with a rare sample of color film footage.

Their next task is to research their objects, finding information to incorporate into a class paper and presentation. Some of their discoveries may enlighten even the UI experts; while the course offers participants an unexpected perspective, it also serves a practical purpose in uncovering vital details about some obscure historic items. Over the next week, the students will need to apply the skills of a detective and an Antiques Roadshow specialist. McCartney dispatches them on their treasure hunt with an admonition: "Don't just search on Google!"

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

Although Svendsen and Pottebaum start by typing "foam head" into the Google search box, they find their first real clue on another website: the online community of Pinterest. On one of its Pinterest boards dedicated to "amazing archives, art, oddities, and wonders," UI Special Collections staff posted an image of the head, identifying it as part of the personal papers of UI Director of Admissions Emil Rinderspacher, 70BA, 74MA.

When Pottebaum arranges to meet Rinderspacher to learn more about the mysterious object, the online and real worlds intertwine. "Digital and physical go hand-in-hand," says Adrain, collections manager for the paleontology repository in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences' geosciences department. "Together, they tell a more complete story of an object than either can do individually."

Rinderspacher's revelations eventually lead Pottebaum and Svendsen back to the digital archives, where they discover Daily Iowan articles from 1970 that document the foam heads' role in campus demonstrations against the Vietnam War. A vocal opponent of U.S. policy in Vietnam, Rinderspacher was one of five students who founded the university's Center for Draft Information and Counseling, which ran from 1970 to the end of the draft in 1973.

As a memento of that tumultuous time in U.S. history, Rinderspacher kept one of the foam heads used in UI campus protests. Art students created about 100 of them, including some with horrifying wounds that reveal brains spilling out of shattered skulls. One spring morning in May 1970, they hung the chillingly lifelike objects from trees across the Pentacrest, along with red-lettered signs declaring, "No More War."

While the digital archives provide plenty of such pertinent details and images, Pottebaum finds his meeting with Rinderspacher much more rewarding. In this informal, 30-minute chat, he gains a vivid, authentic perspective on the turbulent 1960s and '70s. "I was awestruck; I could barely say anything," he admits. "Afterwards, I was so motivated to finish the class project— it was a fervor I've never felt before."

Through such encounters, history not only comes to life—it becomes personal. Hearkening back to the ancient tradition of oral storytelling, face-to-face interactions evoke more emotion and response from the listener. "Online information renders history into mere words, mechanically typed out and searched for via a Web interface," says Pottebaum. "Speaking to a living person is far more of a human thing, a feeling that just can't be expressed in words on paper."

Real artifacts also enlist all the senses, not just sight—as well as other human reactions. As Pottebaum and Svendsen gradually uncover its history, their emotional bond with the relic from the past intensifies. Both are political activists and veterans of Occupy protests against social and economic inequality, and Svendsen says, "When I held the foam head, I sensed the timeless, transcending nature of human rebellion. People have shared experiences through objects."

While these two students realize their place in a historic continuum, another classmate helps reinstate a lost part of the UI's history. Lindsay Schroeder's selected item had been found where it clearly didn't belong—languishing in a closet full of old animal hides in the attic of Macbride Hall.

Peering closely at the portrait of the unknown man, Schroeder manages to discern the artist's signature—Marie Koupal—and the date, 1882. A Google search for Marie Koupal leads Schroeder to an online Daily Iowan article from November 19, 1920, which reveals the distinguished-looking man to be Mark W. Ranney, a physician who once worked at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics.

Ranney died from acute pneumonia on January 13, 1882, and his wife donated his 3,700 books, art collection, and personal papers to the UI as a memorial library in his honor. Until the 1930s, the portrait stood on an easel in the Mark Ranney Memorial Library, the nucleus of the UI's Special Collections department, in South Hall and then Schaeffer Hall. Exactly when and why it was moved to the Macbride Hall cupboard remains unknown.

"The portrait was forgotten, along with the institutional memory of it," says McCartney, who explains that such disappearances happen frequently, especially after a fire, flood, or other disaster. He hopes eventually to display the portrait in the library—to bring it back to its rightful place and "close the circle" of Ranney's gifts to the university. "The philosophy of collecting and caring for tangible objects plays a big role in Dr. Ranney's collection of rare books," says Schroeder. "He's a great example of why people collect items—and, in turn, inspire other people. It was an honor to explore this artifact and guide its history forward for others."

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

PHOTO: TOM LANGDON

When the students select their objects, McCartney warns that they're taking a gamble, saying, "Not all objects are created equal." In fact, some turn out to have impressive provenance. The 1939 Hawkeye football memorabilia document one of the biggest wins in school history, when the legendary Iron Men vanquished the Fighting Irish and Nile Kinnick set a still-unbroken record of 16 punts for 731 yards. The metal thimble reflects a momentous time in U.S. history, as it was distributed during Herbert Hoover's 1928 presidential campaign to attract women voters who had gained suffrage eight years earlier. During "the year of the woman voter," historians believe that Hoover became the first major presidential candidate to receive more votes from women than men.

Despite the best efforts of high-tech Google searches and old-fashioned detective legwork, though, other artifacts from the class remain enigmas.

"This process opened my eyes to the hard job that preservationists, archivists, and researchers have in finding out just what an item is," wrote student Courtney Shelly in her paper on an antique medical instrument.

"[I'm impressed with] people who do this every day and help others understand the importance of objects from the past."

In fact, this UI class may have created a mystery that will one day challenge future generations of researchers.

Inspired by the course, Svendsen and Pottebaum fashion a model of the foam head. Imagining how it must have felt to be a student on May 13, 1970—to walk across campus and see dozens of such heads swaying from trees in mute protest—they take their replica to the Pentacrest. Recording their actions for a Youtube video, they set a "No More War" sign in place and then string up the head with a length of hemp twine. A few passersby pause, smile, and look intrigued.

Hours later, when the two students emerge from class, the head has vanished. Did someone throw it in the trash? Take it home? Svendsen and Pottebaum are content not to know, although they hope that someone has connected with it, the way they did with the original.

Perhaps a few decades from now, the replica head will end up in UI Special Collections, where another student will open an archival box, carefully remove the piece of history, and wonder.

Democratizing History

Since the 1990s, academic institutions, federal agencies, and commercial companies have experimented with using digital technology to 'democratize" knowledge, making vast quantities of information, documents, and artifacts widely available—anywhere, anytime, to anyone with a computer and an Internet connection.

People can post their own personal memorabilia, such as photographs or diaries, which may not be represented in "official" histories, as well as engage with items and each other through interactive functions.

One of the earliest, large-scale digital projects at the UI occurred in 1998, when the Library of Congress and Ameritech funded the online Traveling Culture collection , about the early 20th-century Chautauqua shows that brought thousands of lecturers and performers to small-town America. The UI was among the first institutions nationally to collaborate with the Library of Congress on digitizing such historical materials for the American Memory project.

"At one time, there was the notion that easy access to digital collections would decrease interest in and use of real collections," says UI Archivist David McCartney. "In fact, it's attracted more users who originally saw items online. When people become aware of the collections via digital, they still want to see the real thing."

In other ways, digital technology has decreased the use of some real artifacts. UI librarians no longer have to lug the physical volumes of archived Daily Iowans to a reading room; people can browse them online. In such cases, people want the information—not necessarily to see and experience the original newspaper.

One of the strengths of digital technology is its ability to search quickly through an enormous amount of data and find what people are seeking. Plus, it helps reduce wear and tear on original artifacts or documents. From that perspective, says McCartney, "digital is also a great preservation strategy."

Sloths, CAT Scans, and Shark Sinuses

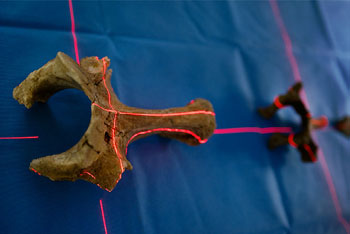

It's an age-old dilemma for museum curators: how to preserve and investigate unique historic artifacts without causing irreparable damage. In such a case several years ago, modern technology saved a prehistoric creature.

Paleontologists had unearthed a rare family of extinct Ice Age sloth on a farm in southwestern Iowa, but some remains were too fragile to move safely. So, the archaeology team encased the remnants in a plaster cast, sent them to University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics for a CAT scan, and then provided the scan results to College of Engineering faculty who created an exact 3-D replica of the sloth bones. Now, researchers and students can examine and learn from the replica without harming the original.

Even though she's surrounded at work by artifacts that are millions of years old, Tiffany Adrain, collections manager for the UI's paleontology repository, is used to enlisting such high-tech options to open up a whole new world of discovery. At a conference, she's even taken a virtual tour inside the nasal passages of a shark. The computer software that manipulated, magnified, and enhanced a series of scans of the shark's head offers a dramatic example of technology's ability to provide access to previously unimaginable places and knowledge without sacrificing rare specimens.

Of course, as Adrain acknowledges, the memorable shark adventure also shows that "digital enhances the original, but we still need the original object to be able to make it happen."